Northern roots

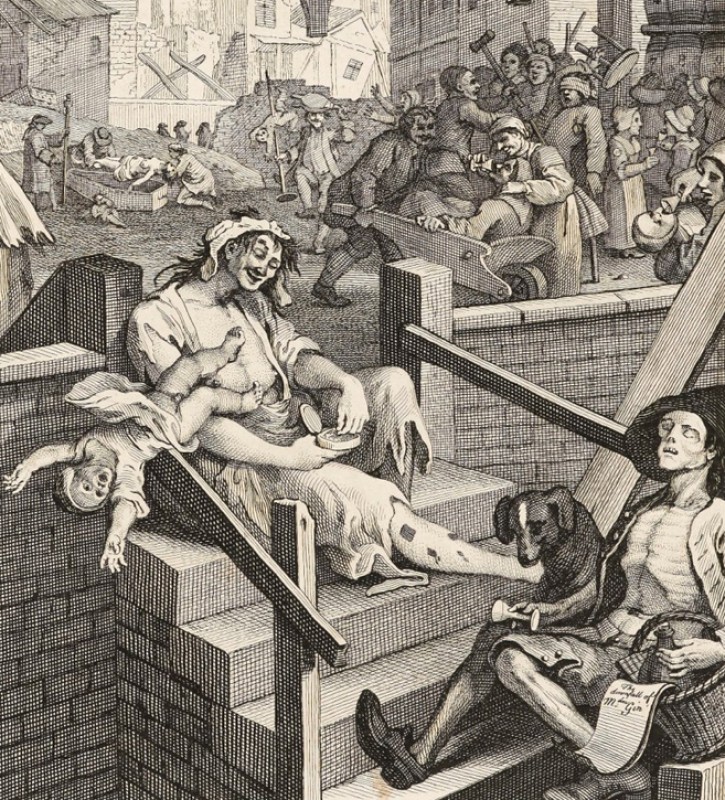

Genre scenes were popular in northern Europe, especially the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. Painting of this type depicted a wide variety of subjects, from rowdy taverns and busy kitchens to milkmaids and housewives absorbed in their work.

What's more, genre painting focused on the everyday lives of people, both high and low, and were sought after by an emerging middle class with money to spend.

The beginnings of genre painting can be traced to the sixteenth-century peasant scenes of Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the elder.

In the Netherlands during 1620–30, Frans Hals and Adriaen Brouwer were some of the first artists to paint genre scenes, often focusing on drinking and merrymaking.

Throughout the Dutch Golden Age, artists such as Johannes Vermeer, Jan Steen and Pieter de Hooch gained a reputation as masters of the genre – Vermeer in particular stands out for his quiet, contemplative works.