In an age where we have become accustomed to limited attention spans and equating significant art with instant impact, there was a time not that long ago, when there was room for stoicism, consummate draughtsmanship, poetry and quiet contemplation.

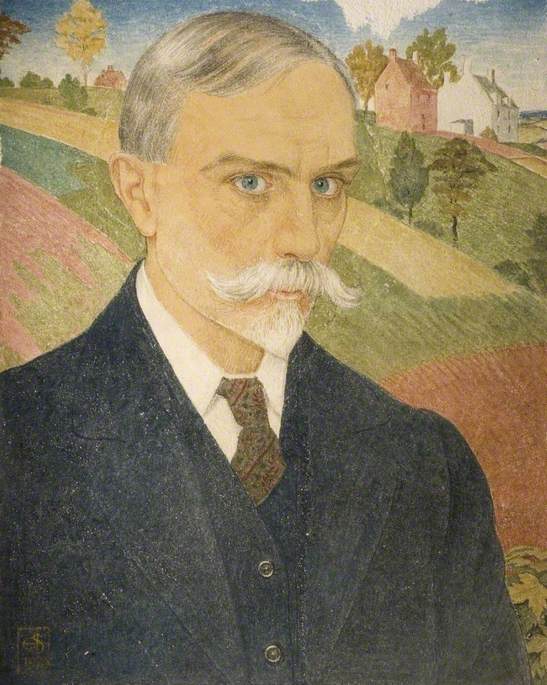

The art of Frederick Cayley Robinson exemplifies all of these virtues and though largely forgotten in the decades since his death in the 1920s, his work is on the brink of a revival.

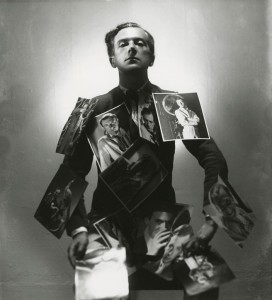

Born at Brentford-on-Thames in Middlesex on 18th August 1862 as Frederick Arthur Robinson – sometime before the 1891 census, he adopted the more distinctive 'Cayley Robinson' in a nostalgic gesture to his great-great-grandfather John Cayley, an eighteenth-century Russian merchant.

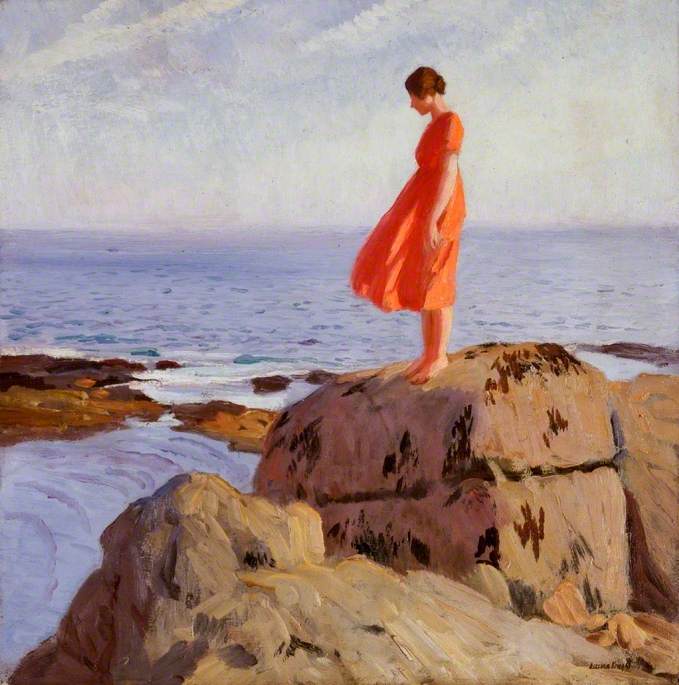

Frederick began his art studies at the St John's Wood School of Art in London and later enrolled at the Royal Academy Schools in March 1884. For two years after leaving the Royal Academy he sailed around the British coast on his yacht visiting artist colonies in Cornwall.

It was a period of radical change in coastal genre painting in Britain which was being recast by a new generation of painters anxious to break with conventional scenography artists.

This new form of capturing the world is shown in Cayley Robinson's early works in the naturalistic style of Jules Bastien-Lepage, the great champion of Realism whose work was the sensation of the Grosvenor Gallery, London in 1880.

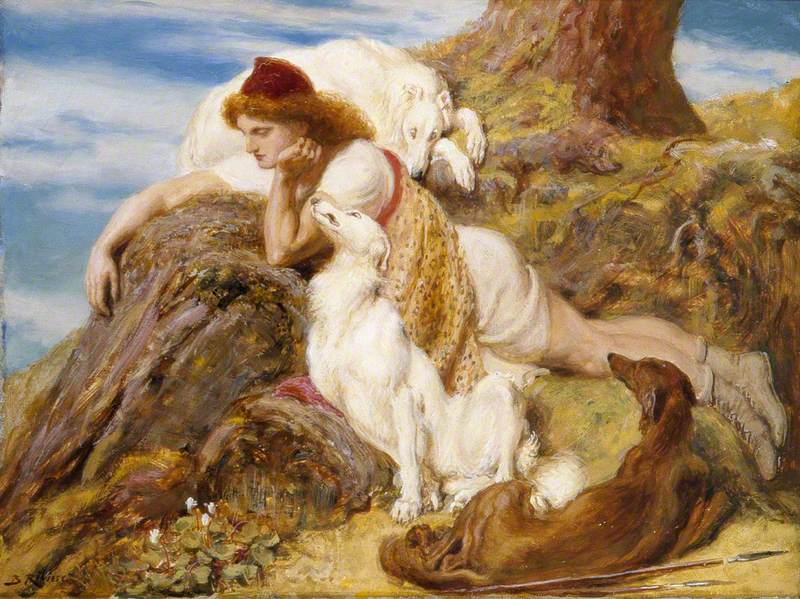

Another work shown at the Grosvenor Gallery, four years later, was to have an equally mesmerising effect on Cayley Robinson; King Cophetua by Sir Edward Burne-Jones is based on Alfred Lord Tennyson's poem The Beggar Maid. The painting established Burne-Jones' reputation in France when it was shown at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris five years later.

French artistic training in the late decades of the 1800s was seen as infinitely preferable to that of the London art schools as it laid greater strictures on accurate observation – and so it was that Frederick journeyed to experience the mêlée of Paris in 1891 to study at the Académie Julian.

Little is known about this formative period in his career, though he was an active participant in the intellectual life of Paris when the city was common ground to such musicians and painters as Claude Debussy, Paul Gauguin and Georges Seurat.

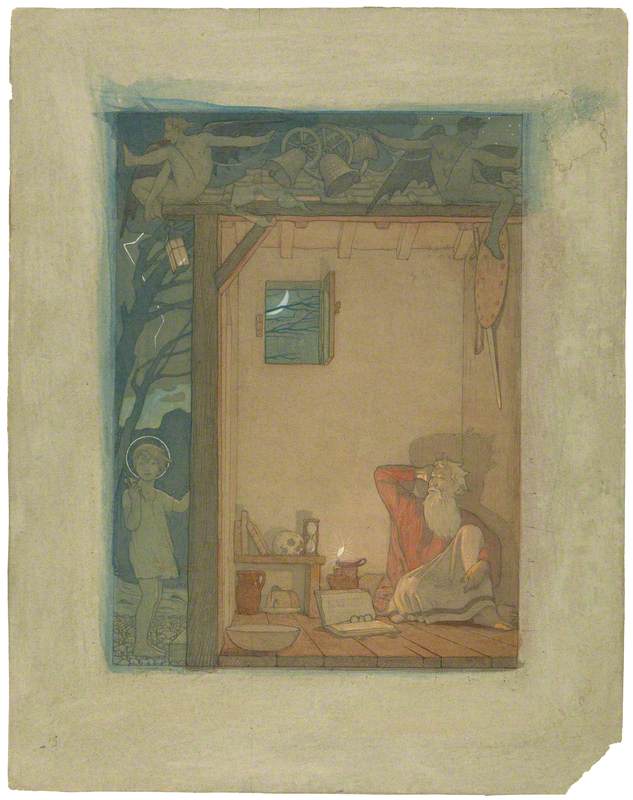

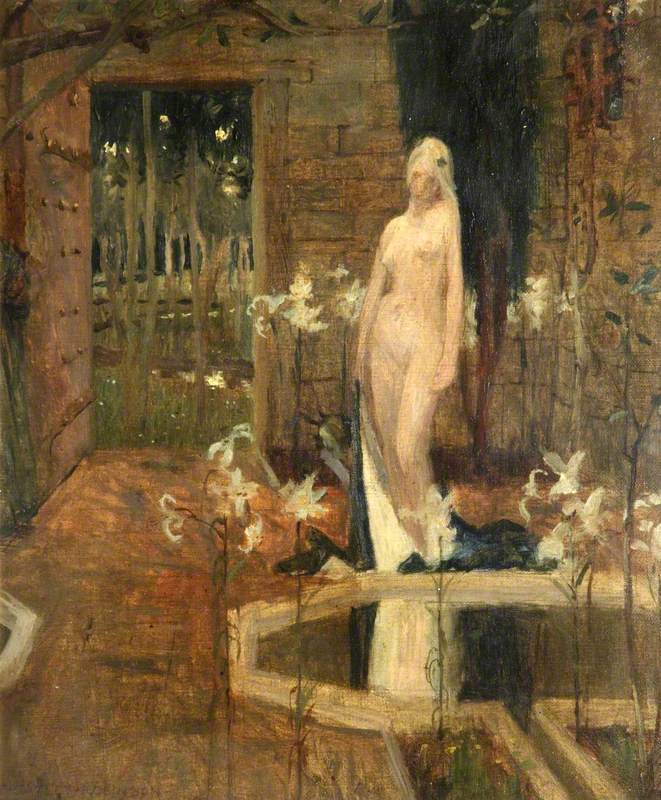

We can be more certain that this period altered his style of painting. His oil sketch Female Nude in a Garden, with the figure of the Virgin Mary in a walled garden (the medieval symbol of virginity) was influenced by the popularity of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints and is shown here in the balancing of space against areas of strong patterns.

The theme of purity also forms the focus of In a Wood So Green. Made in 1893, the painting is a retelling of the story of Arthurian legend.

The full moon drifting in the darkening sky behind the knight’s helmeted head, so it appears as a halo, is emblematic of unreachable ideals. This is surely Galahad or Sir Launcelot and among the beech trees is Morgan le Fay.

On his return to England in 1894, Cayley Robinson executed a painting which would become characteristic of his early work. Threads of Life is a scene of a woman and a child in a small, cramped room, which takes on strange and even ominous characteristics after a time.

A major influence on Caley-Robinson came in 1898 when he married the artist Winifred Lucy Dalley on Tuesday 6th December at St Katherine's Church in the village of Holt in Wiltshire. The couple celebrated their honeymoon by starting a new life in Florence.

Here Frederick had the opportunity to study the works of the artists of the Italian Renaissance whose influence we find in his later work. While in Italy, Cayley Robinson experimented with painting in tempera, a medium then undergoing a revival. He missed out on the 1901 exhibition at the Carfax Gallery in London dedicated to paintings in tempera, by having no work ready to hang.

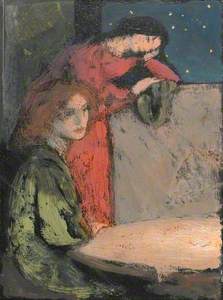

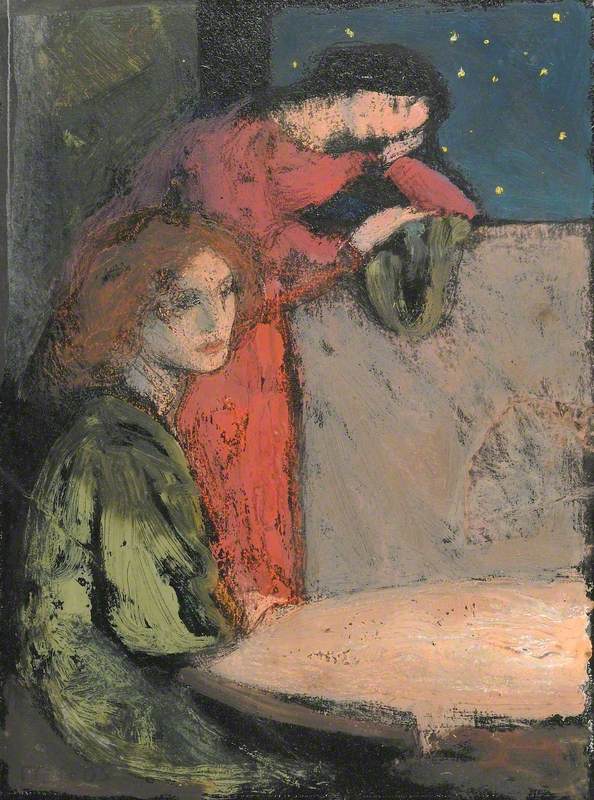

Two Girls by a Table Look out on a Starry Night

1905

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

The Robinsons returned briefly to England in 1902 to baptise their daughter Barbara, then set off for France where they lived for four years. Frederick was back in London in 1904 where he held his first solo exhibition of 56 paintings (all in tempera) at the home gallery of the New Zealand artist John Baillie in Prince's Terrace, Bayswater in London.

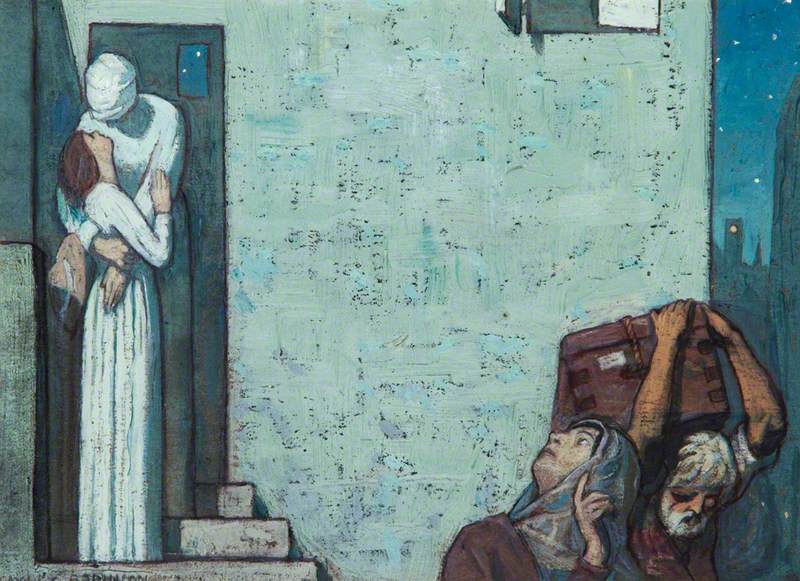

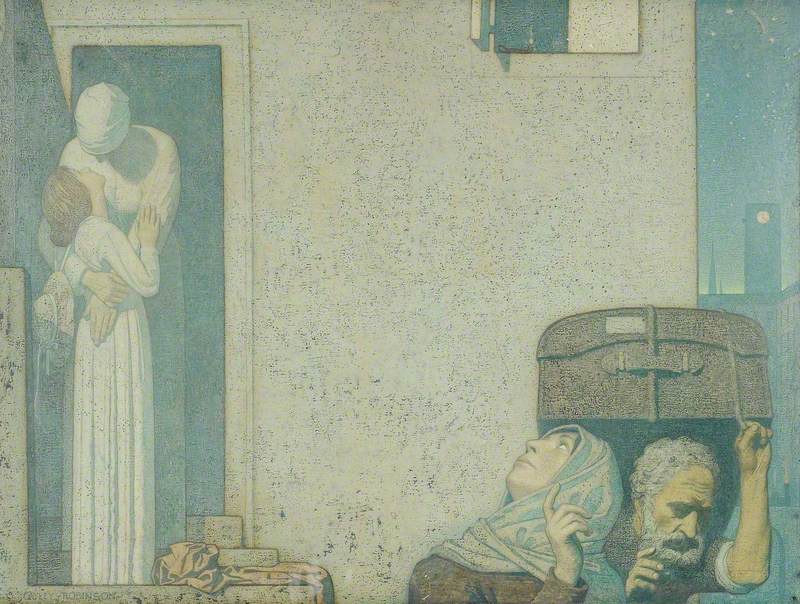

It was a landmark exhibition in his career; a painting from this time The Night Watch (1903) anticipates Neo-Romanticism by several decades and demonstrates how Robinson's style, medium and subject matter had undergone a radical transformation.

So what was pulling Robinson's imagination in a new direction?

The period after the heyday of Impressionism, involved a fantastical melange of realism and fantasy as artists strived to create mythic art for modern times; the explanation for the drastic change in Robinson's style can be found in his interest in the Theosophy movement.

Theosophy had been founded in 1875 and grew out of Victorian spiritualism and yet also went back to older belief systems such as Neoplatonism, which preached the existence of a higher reality beyond the world we can see.

The connection between Theosophy and art began in the late nineteenth century, when a number of artists and writers reacted strongly against the materialism of an age dominated by science and industrialisation.

In an 1891 essay by the critic Albert Aurier for the literary and arts magazine Mercure de France, he stressed the symbolical, and decorative functions of art which, without explicitly painting a subject, alluded to it visually.

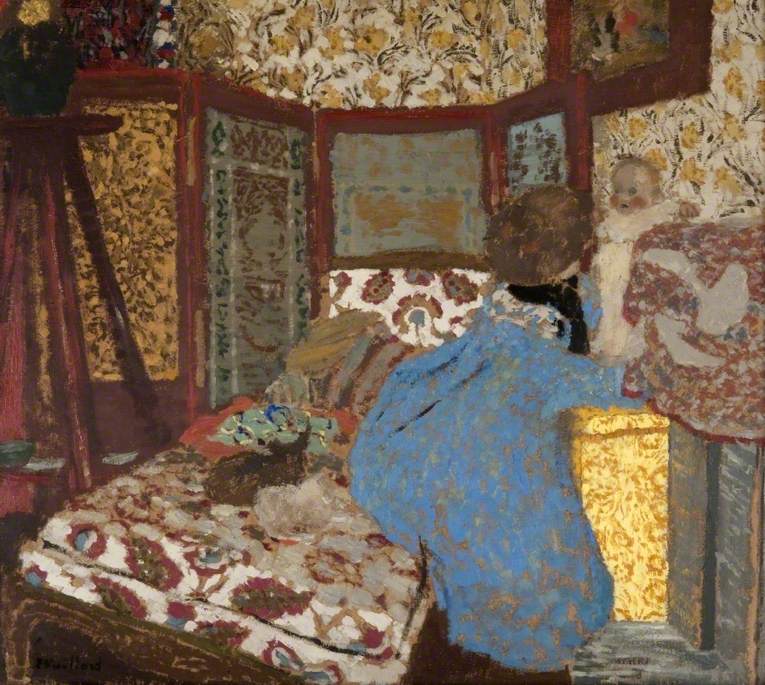

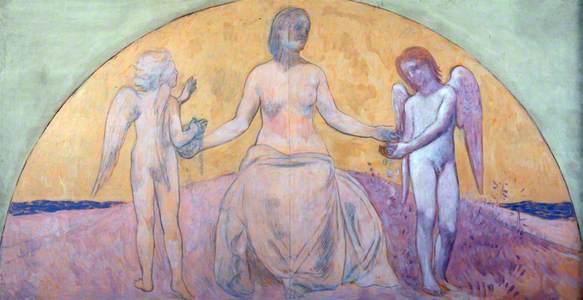

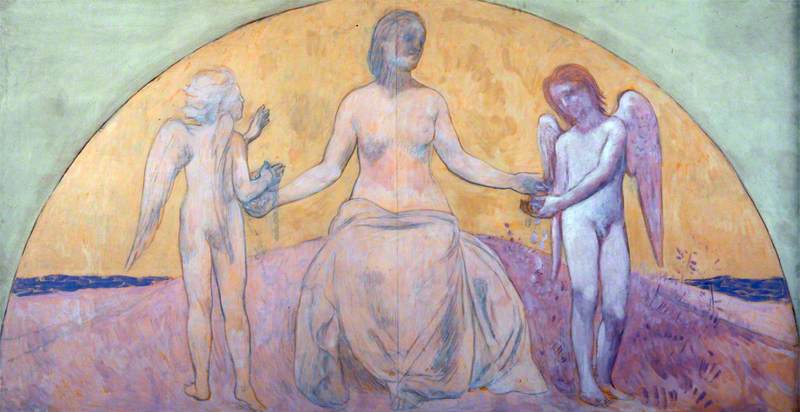

The painters who were indeed representative of this Symbolist aesthetic included the Frenchman Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who developed a style characterised by simplified forms, rhythmic line, and pale, flat and a fresco-like palette for allegorical pieces and idealisations of themes from antiquity. These conveyed abstract ideas, rather than actions or events.

Charity: A Sketch (A Woman Distributing Gifts to Two Winged Children)

c.1889–1893

Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898)

Into this mix came the influence of the Renaissance master Piero della Francesca; not only is this apparent in general tonality and mood of Robinson's work but we an almost obsessive use of the golden ratio, a geometric proportion in the Renaissance regarded as the key to creating aesthetically pleasing art. It is this which leads us back to Theosophy's belief in the golden ratio's ubiquitous presence in all things.

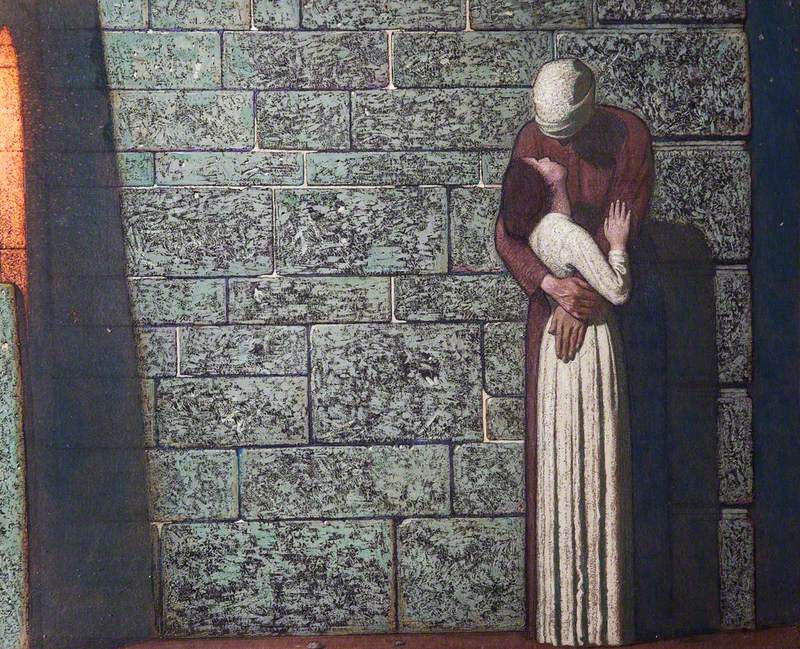

In Robinson's Farewell, from 1906, we can see these influences at work. The attenuation of hands and the slightly schematic folds of drapery are also highly reminiscent of Gothic art.

Robinson's 1908 show at the Carfax Gallery, Bury Street in London was highly praised; later that year he was asked to be a member of the hanging committee of the first Salon of Allied Artists' Association (AAA) held at the Royal Albert Hall in London.

Robinson's set designs for the Belgian Symbolist playwright Maurice Maeterlinck's 'fairy play', The Blue Bird, which premiered at the Haymarket Theatre, London the following year were universally praised with one writer saying there were 'almost divine in their symphonic loveliness of colour and design.'

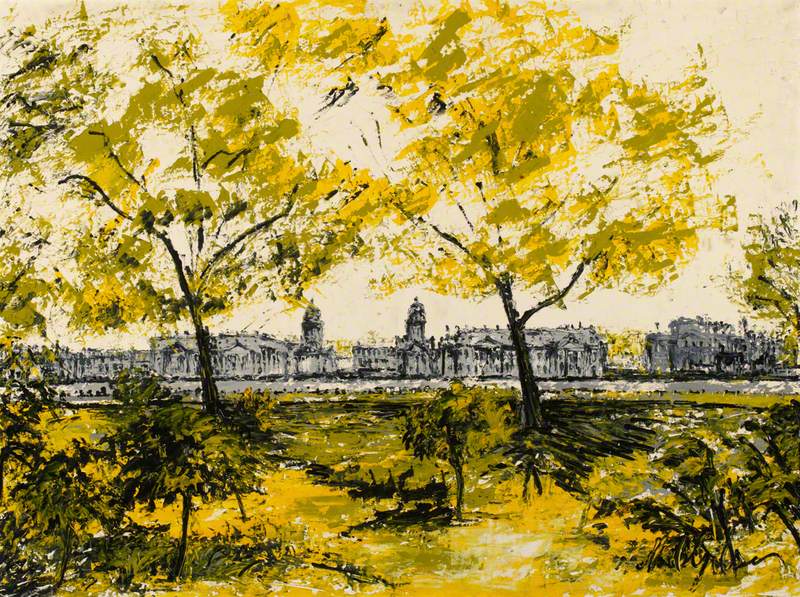

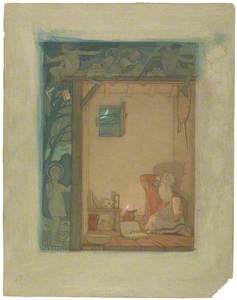

The Landing of Saint Patrick in Ireland

c.1912

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

In 1912, Robinson was awarded two important commissions for mural paintings: the New Gallery of Modern Art in Dublin with his design The Coming of Saint Patrick, and a further commission from the art collector and mining tycoon Edmund Davis, to decorate the vestibule of the Middlesex Hospital, after the original competition had failed to find a winning design.

The first panel for the Middlesex Hospital mural Acts of Mercy was finished in 1915 at Frederick's studio flat in Lansdowne House, Lansdowne Road in London (the flats had been built by Edmund Davis) after the family's move from 37 Cyril Mansions in Battersea where they had lived since returning to London nine years previously.

Orphan Girls Entering the Refectory of a Hospital

1915

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

The painting depicts young orphaned girls (hospitals had traditionally brought up and supported orphans) sitting and standing around a refectory table, a motif of Leonardo's Last Supper, while their stillness and pure complexions are reminiscent of portraits from the Quattrocento.

To the left of the first panel, the girls process down a staircase, a device borrowed from Sir Edward Burne-Jones' The Golden Stairs (1880) and in the second Orphans panel (1916) the girls, in a continuing procession, are now adolescents working as nurses, as was often the case in the real world.

Orphan Girls in the Refectory of a Hospital, Proceeding to Their Place at the Table

c.1915

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

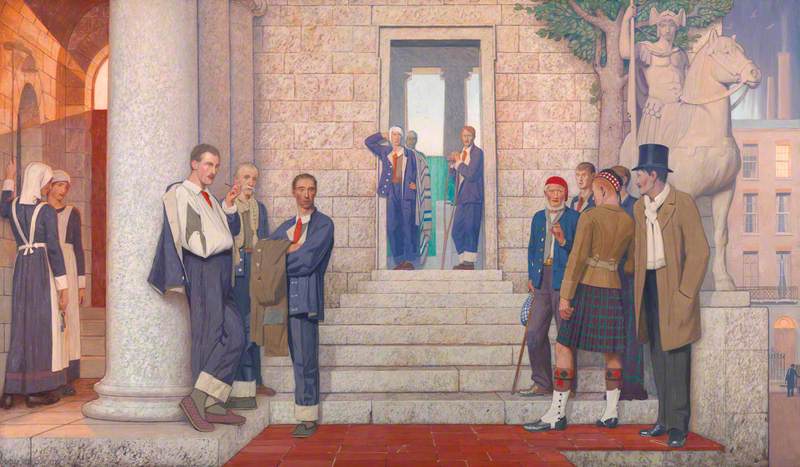

The initial The Doctor panel of the series (completed in 1920) has the surviving wounded of the First World War, some in uniform, others in their blue invalid uniform or 'convalescent blues', looking shell-shocked as they stand around the steps of the hospital as if they are unable to comprehend their past or future.

Wounded and Sick Men Gathered Outside a Hospital

1920

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

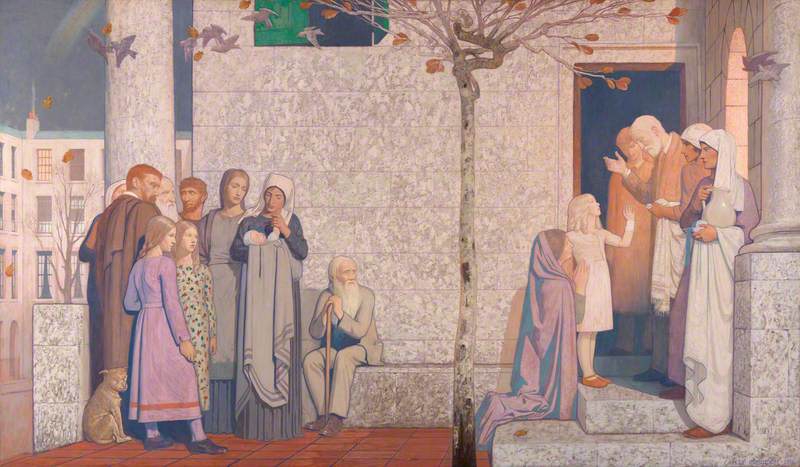

The final painting, but the third to be completed in 1916, has among the standing figures, a flock of swallows symbolising the Resurrection and an autumnal birch tree representing the determination and overcoming of difficulties. Outside the rear door, a Christ-like doctor is raising his hand over an injured child and her kneeling mother, in an act of benediction.

Men, Women and Girls Standing in a Group Outside a Hospital

1916

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

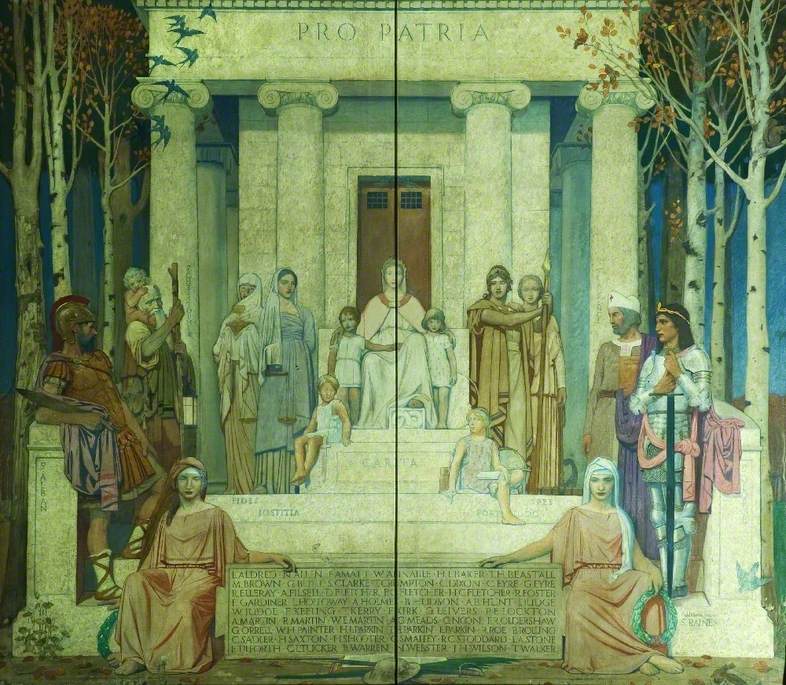

By now an Associate of the Royal Academy, when his final mural – a triptych commissioned by Heanor Secondary School in Derbyshire to commemorate the 57 former pupils who had died in World War One – was shown at that institution's 1922 Winter Exhibition of Decorative Art, it was warmly appreciated by art critics.

World War Memorial to the Students of Heanor Grammar School

(triptych, left wing) c.1919

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

The central panting of the work is made up of various allegorical figures representing Peace, Justice, Charity, Fortitude and Hope. At the sides are the devices of birch trees and swallows, Robinson used in the Middlesex mural.

World War Memorial to the Students of Heanor Grammar School

(triptych, centre panels) c.1919

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

This repetition is not unusual in Robinson's paintings, we can see in much of his work common motifs and decorations which he recycled and reworked, creating variety by giving them different elements, colouring and changing their scale.

World War Memorial to the Students of Heanor Grammar School

(triptych, right wing) c.1919

Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927)

In 2015, the three paintings which make up the triptych were removed from their mounts, rolled up and put into storage. The site and all contents of the school were sold to a local housing developer.

My attempts at asking the conservators for a report on the mural's present condition and recent photographs for this article have not been answered; the local authority, Amber Valley District Council is in negotiations with the present owner to have the triptych put back on permanent display. A campaign group has been formed to have the mural exhibited in Heanor.

The 1920s were a fruitful period in Robinson's professional and private life. Of the paintings which most stayed in Cayley Robinson's imagination, Puvis de Chavannes' single most famous work The Poor Fisherman (1881) impressed him the most and we can see how the composition in Pastoral (c.1924) is indebted to this picture.

Le Pauvre Pêcheur (The Poor Fisherman)

1881, oil on canvas by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898)

The painting could be read as a dream of escape. Suggesting a peaceful and untroubled time, the figures in this work are in Arcadia, that utopian vision of pastoralism and it is perhaps no coincidence this vision occurred to him after contracting pneumonia.

It was a year which also saw Robinson join the Art Council and Art Working Committee of the British Empire Exhibition which was held at Wembley in 1924. Now into his 60s, he continued to be a motivating force behind painting in tempera and exhibited at several exhibitions but he was in frequent poor health and died aged 64 from pneumonia on 6th January 1927.

Following his death, memorial exhibitions were held at both the Royal Academy (Winter 1928) and Leicester Galleries (1929). The nearest to a retrospective of his work was held at The Fine Arts Society, London in 1977.

So how should we remember Frederick Cayley Robinson?

The French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé had once described the idea behind his poem Herodiade in a letter to his friend Henri Cazalis, writing: 'I've invented a language which has to spring from a new notion of poetry. I could define that new notion in two phrases. Don't paint the thing itself. Paint the effect it produces.'

To view Frederick Cayley Robinson's body of work with all its ambiguities, calm, perfect depictions of light and superb draughtsmanship, is to realise that he was one of the very few British artists of his generation to have embodied and achieved Mallarmé's ideals.

Richard Morris, art historian

With thanks to Amanda Bradley, Dr Alice Eden, Christopher Fiddes and Dawn Lonsdale, Chair of the Heanor Grammar School Action Group

Further reading

Journal of the Royal Society of the Arts, Volume 60, No. 3,110 (June 1912)

The Connoisseur magazine, September 1977

William Schupbach, Acts of Mercy: The Middlesex Hospital paintings by Frederick Cayley Robinson (1862–1927), Wellcome Institute, 2009

Katherine M. Kuenzli, The Nabis and Intimate Modernism: Painting and the Decorative at the Fin-de-Siècle, Routledge, 2010

Albert Aurier, 'Le symbolisme en peinture. Paul Gauguin', Mercure de France, 2:15 (March 1891), pp. 155–165