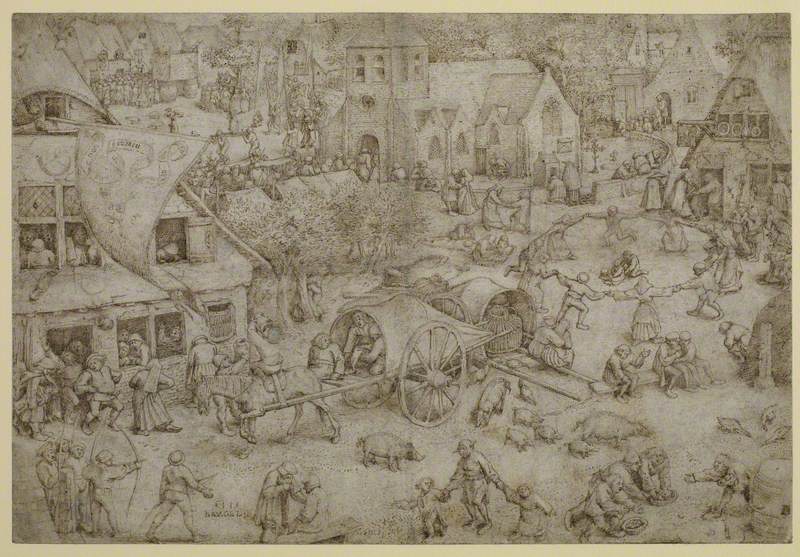

(b ?nr. Breda, c.1525; d Brussels ?(5 Sept.) 1569). Netherlandish painter, draughtsman, and printmaker, the greatest artist of his time in northern Europe. There is little documentary evidence concerning his career, our knowledge of him depending mainly on van Mander's laudatory biography, published in 1604. This is a lively and useful source of information, but it misleadingly projects an image of Bruegel as ‘Pieter the Droll’, essentially a comic painter: ‘there are few works by his hand which the observer can contemplate solemnly and with a straight face’. Certainly there is humour in his work, but this is part of what Kenneth Clark calls his ‘all-embracing sympathy with humanity’, and his vision also includes horror, tragedy, and the implacable forces of nature.

Read more

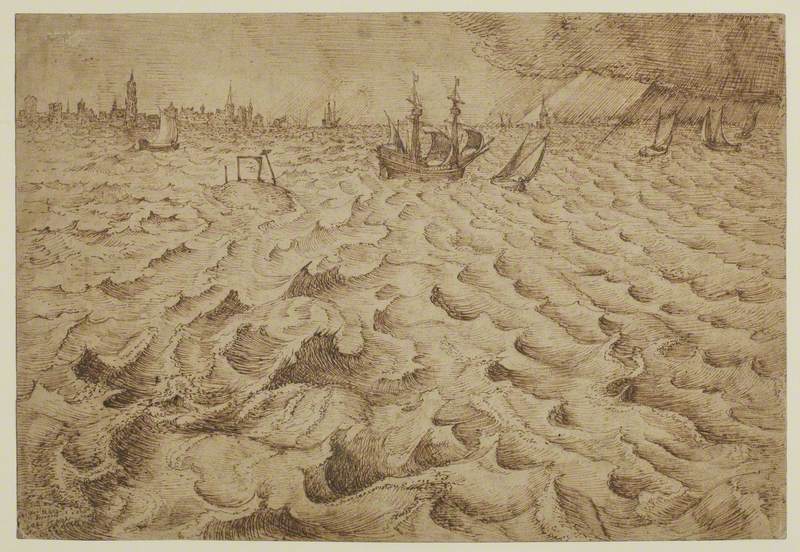

Far from being the yokel of popular tradition—‘Peasant’ Bruegel—he seems to have been a man of some culture: his work includes memorable scenes of village life, but he spent his career in major cities rather than the countryside, he had distinguished patrons, and he was a friend of the eminent geographer Abraham Ortelius (who described him as ‘the most perfect painter of his century’). It is not known where Bruegel was born (van Mander says he came from a village near Breda and took its name as his own, but none of the appropriately named villages is near Breda), and there is no documentation on his life until 1550/1, when he is recorded in Malines, working on an altarpiece that is now lost. In 1551/2 he became a master in the painters' guild in Antwerp, where according to van Mander he had been the pupil of Pieter Coecke van Aelst (who died in 1550); there is no stylistic affinity between their work, but Bruegel later married Coecke's daughter, so it is likely that he had links with her father. Soon after becoming a master, Bruegel made a lengthy visit to Italy, travelling as far south as Sicily. In Rome he met the miniaturist Giulio Clovio, who bought several of his paintings. By 1555 he was back in Antwerp, designing engravings for the print publisher Jerome Cock, who was his main source of employment for the next few years. The experience of crossing the Alps affected Bruegel much more than the example of any art he had seen in Italy, as was acknowledged by van Mander, who wrote that he ‘swallowed all the mountains and rocks and spat them out again, after his return, on to his canvases and panels’. His work for Cock included a series of prints now known as the Twelve Large Landscapes (c.1555–8), featuring wonderfully spacious mountain views. (Most of the drawings of Alpine scenery associated with Bruegel's visit to Italy—as well as many other drawings traditionally given to him—have recently been reattributed to Jacob and Roelandt Savery, who perhaps made some of them as deliberate forgeries.) Bruegel's work for Cock also included figure compositions of various subjects, including parables like ‘Big Fish Eat Little Fish’. The engraving after Bruegel's drawing of this subject (published in 1557), bears the inscription ‘Hieronymus Bos Inventor’, an attempt by Cock to cash in on the continued popularity of Bosch, whose moralistic outlook and sense of the grotesque influenced Bruegel considerably (he was indeed referred to in his lifetime as ‘a second Bosch’). In 1563 Bruegel moved to Brussels and married there in that year. The move coincided with a change of direction in his career, for although he still made designs for engravings, he now worked primarily as a painter, and in the remaining six years of his short life he produced his best-known works. His patrons included Cardinal Granvelle, chief counsellor to Margaret of Parma, the regent of the Netherlands (she was the half-sister of Philip II (see Habsburg), and the wealthy banker Niclaes Jonghelinck, for whom he painted a series of six paintings of The Months (1565), of which five survive today. Three of these (including the celebrated Hunters in the Snow) are in the remarkable collection of fourteen pictures by Bruegel in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, which comprises almost a third of his surviving output as a painter; the other two are in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, and the National Gallery, Prague. His style changed during this final period: he abandoned the crowded panoramas of his earlier years, making his figures bigger and bolder, as is seen most notably in his novel treatment of proverbs, a genre that had previously been of minor account (The Blind Leading the Blind, 1568, Mus. di Capodimonte, Naples). Bruegel enjoyed a considerable reputation in his lifetime (he is mentioned by Vasari and slightly later by Lomazzo), and—through his original works and the many prints after them—he had an enormous influence on later Flemish painting, particularly landscape and genre. It was not until the 20th century, however, that he was recognized also as a profound religious painter and an artist whose human sympathy and understanding have hardly been excelled. In compositional prowess, too, he ranks with the very greatest masters, showing extraordinary skill in arranging large numbers of figures and integrating them with their surroundings. His two painter sons were infants when he died and so they had no training from him (they were reputedly taught by their grandmother—the widow of Pieter Coecke—Mayken Verhulst). Both sons spelled their surname ‘Brueghel’ or (‘Breughel’), retaining the letter ‘h’ that their father had dropped in about 1559.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)

.jpg)