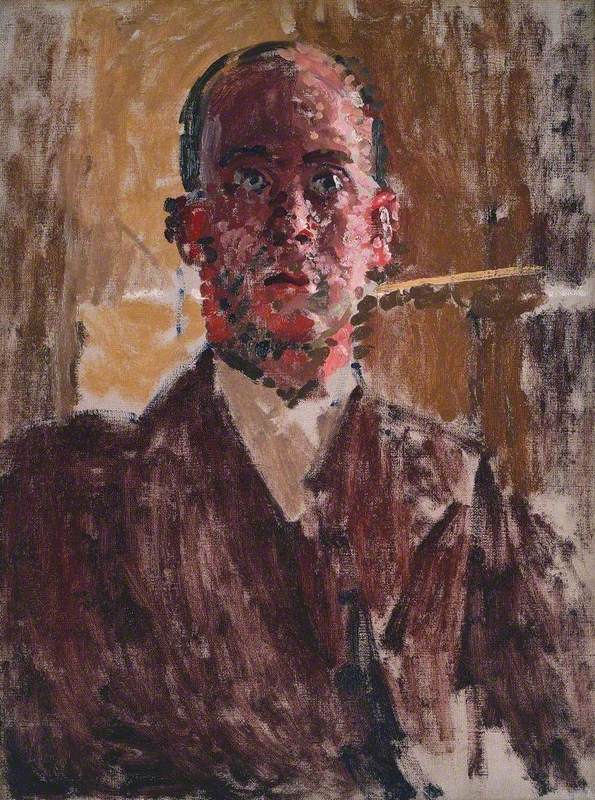

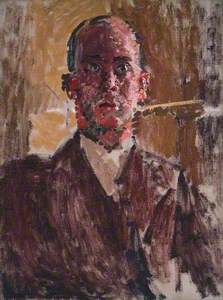

In a six-decade career that spanned the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Walter Sickert (1860–1942) transformed how British artists captured everyday life and, by doing so, he laid out paths for several modern masters. Yet while he is justly celebrated as an artistic pioneer, question marks remain over his character.

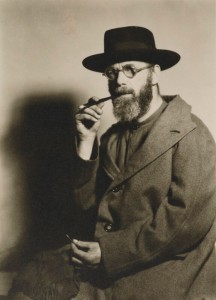

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Walter Sickert

1911, vintage photograph by George Charles Beresford (1864–1938)

Sickert's interest in marginalised society, along with his obsession with a series of infamous murders by Jack the Ripper, has left many to wonder how far he was involved in the crimes. This suspicion only deepens when we consider his ability to disguise his identity behind a series of personas, as depicted in the varied self-portraits he created through his working life. Through these he questioned the role of the artist as a protagonist in his own work, even playing roles such as the New Testament character Lazarus or a servant of Abraham.

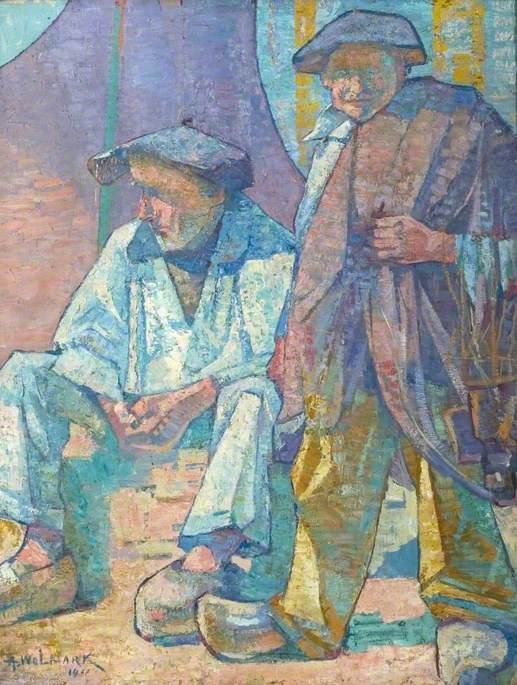

This practice of taking on differing characters has roots in Sickert's early life as an actor, a milieu that provided much subject matter in his later career. His strong connection with the French art world was also key, which at that time was the cutting edge of modernism. This cosmopolitan outlook derives from his upbringing. He was born in Munich, Germany, to a Danish-German father, Oswald Adalbert Sickert, and an Anglo-Irish mother. The family settled in London in 1868.

Despite his father and grandfather, Johann Jurgen Sickert, both having been professional artists, Walter chose to pursue a career on the stage. Though touring with Sir Henry Irving's company from 1877 to 1881, he never gained anything other than small parts, so abandoned this calling to enrol briefly at the Slade School of Fine Art.

After a year, he became a pupil of the acclaimed American artist James Whistler, an important stage in Sickert's development. Acting as a studio assistant, Sickert adopted his mentor's interest in urban subjects and atmospheric use of tones, though the younger artist's brushwork was rougher and more textural.

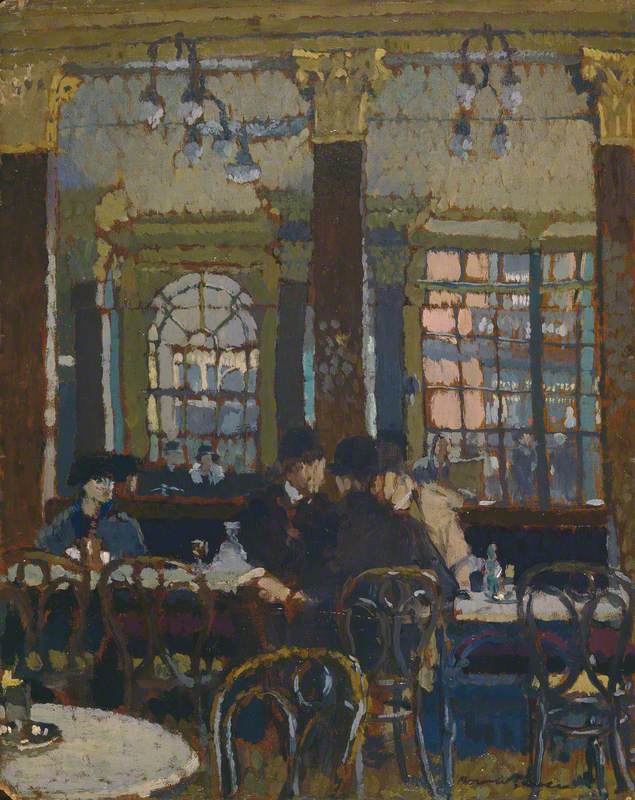

As part of his role, Sickert took Whistler's work to Paris to show in salons, and in 1883 he delivered a letter from Whistler to the Impressionist painter Edgar Degas, who went on to become a close friend of Sickert. Degas' advice and example would have a lifelong impact, especially his encouragement to use bolder colours and also to take on everyday subjects, notably places of popular entertainment, including music halls, circuses and ballet. That year, Sickert based himself in the French capital, finding further inspiration in Édouard Manet's depictions of café-concerts, a cross between bars and variety halls.

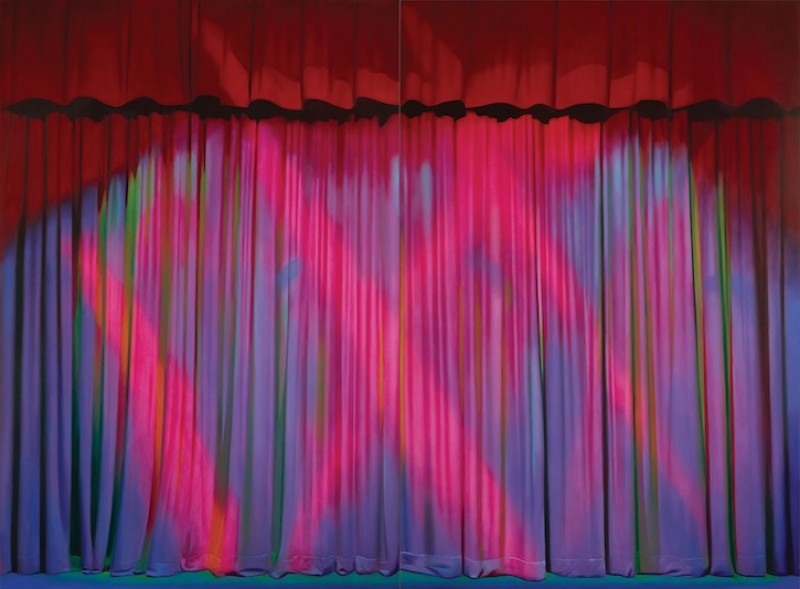

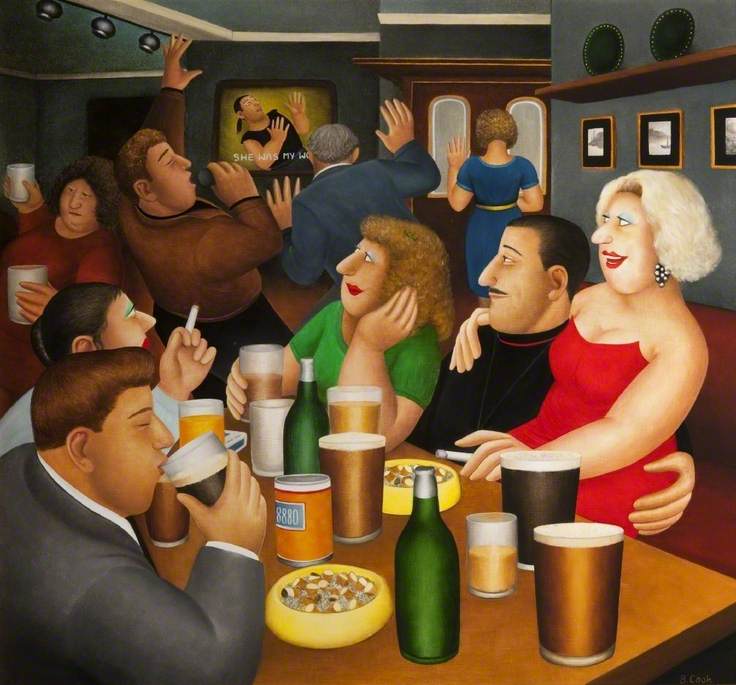

Music hall, among other working-class entertainments, came to be one of Sickert's favourite subjects, even though much of the British art world deemed it to be inappropriate. Beginning with depictions of famous performers such as Minnie Cunningham and Little Dot Hetherington, he widened his gaze to include the audiences, often those in the cheapest seats.

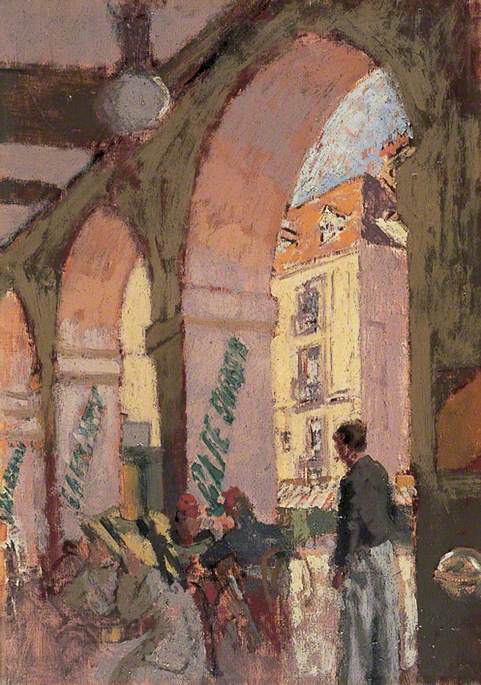

Sickert would ramp up the drama of the stage and auditorium by capturing them from unusual angles that evoked the energy of urban nightlife, both in London and Paris.

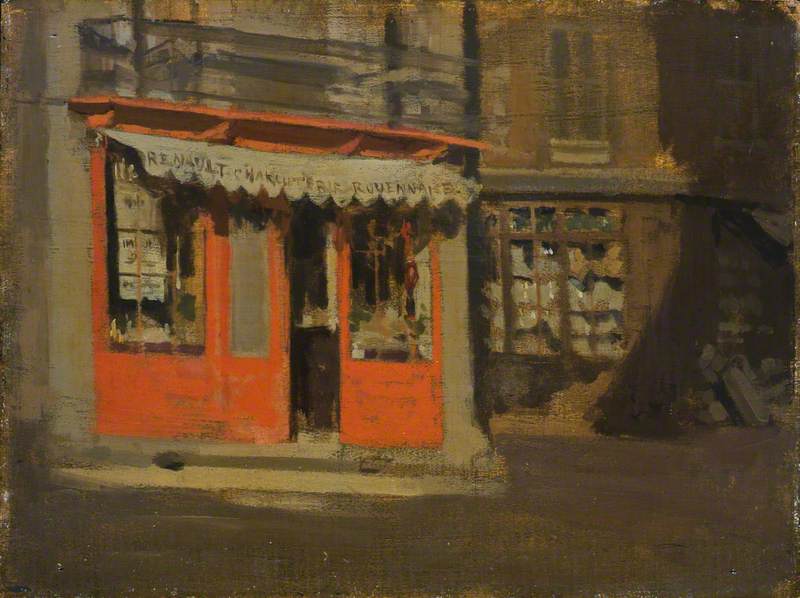

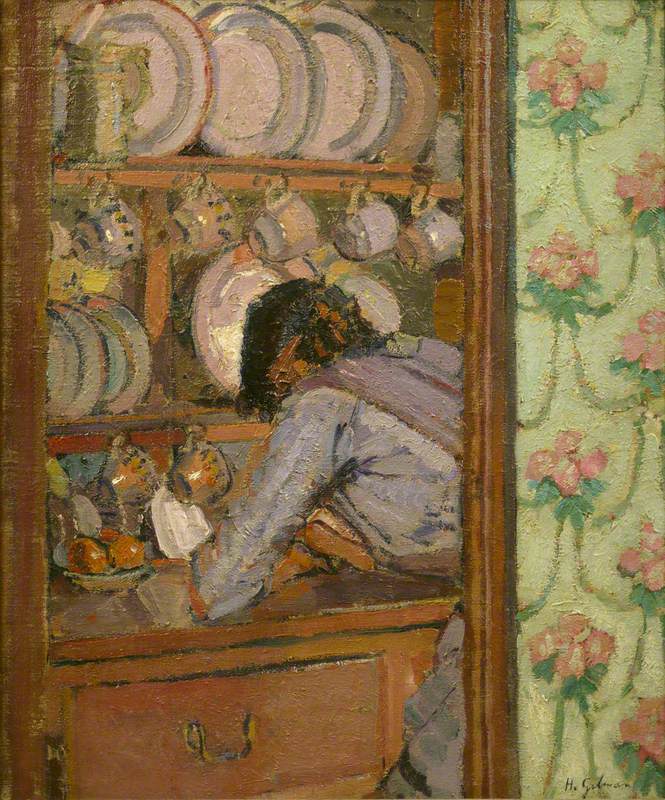

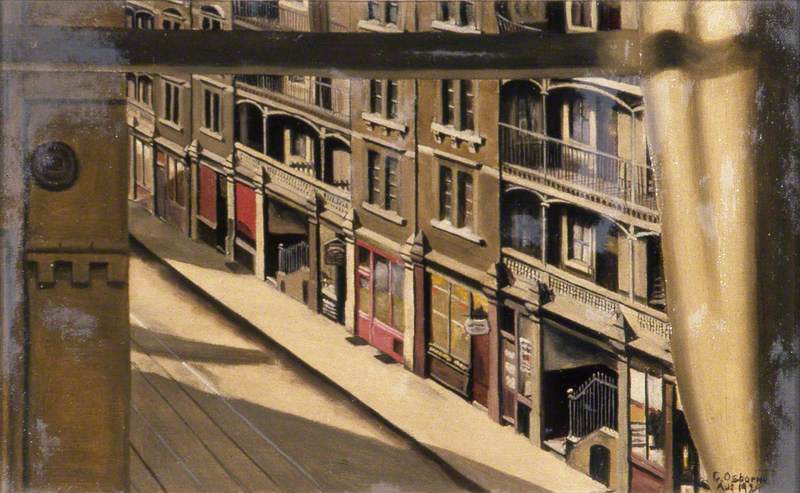

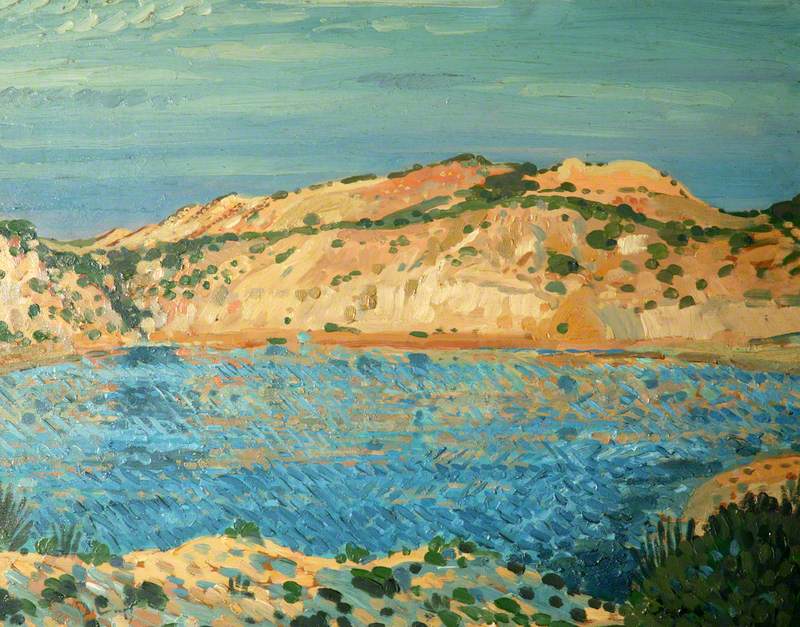

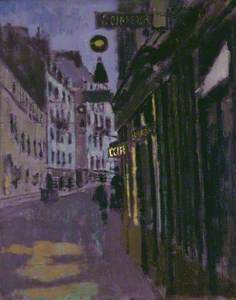

Image credit: William Morris Gallery

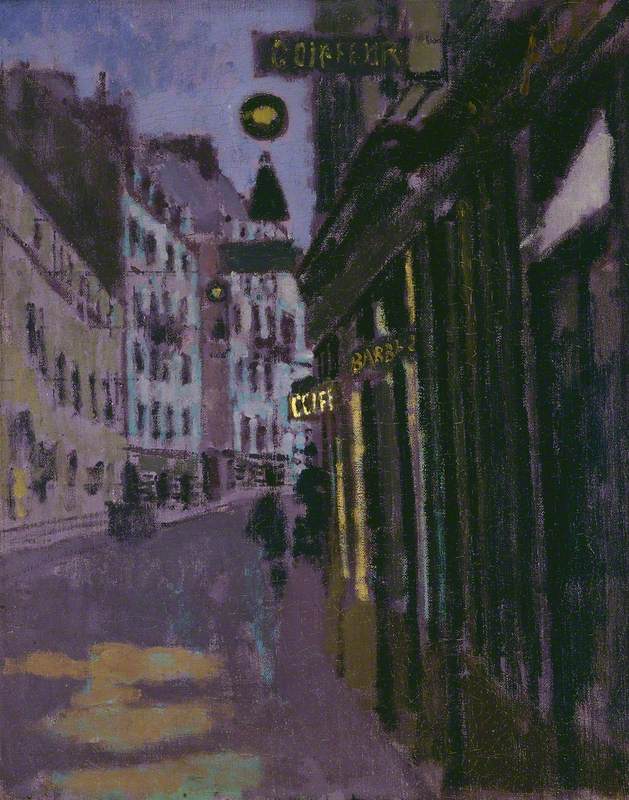

La Rue Notre Dame and the Quai Duquesne 1899–1900

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

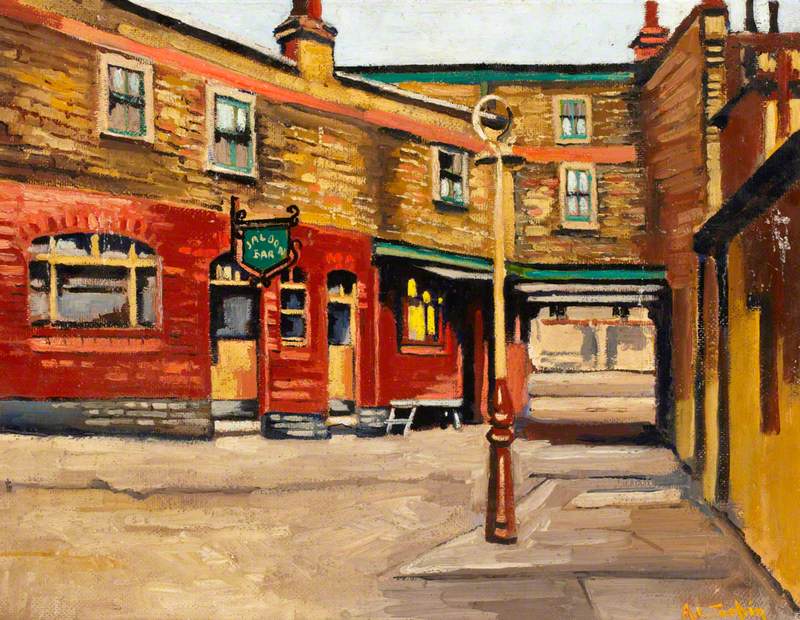

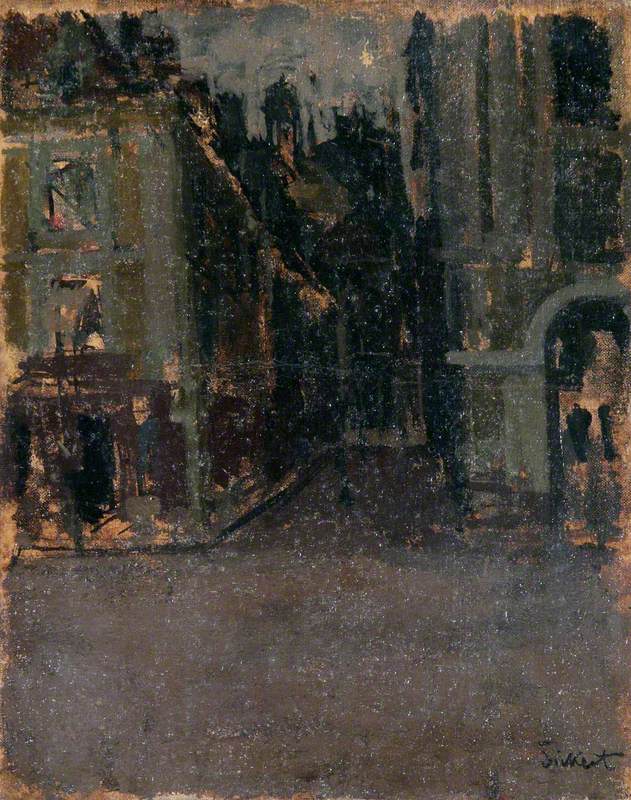

William Morris GalleryBetween 1885 and 1905 he spent much of his time in Dieppe, first travelling there with Whistler and then moving to the Channel port in 1889, returning from 1918 to 1922. Based in the town for long periods, Sickert created a series of works that explored how changing light transformed the façades of buildings, and favourite sites including Rue Notre-Dame and the Hotel Royal.

He continued this practice in Venice, which he visited several times from 1895 onwards, focusing largely on the famous St Mark's piazza.

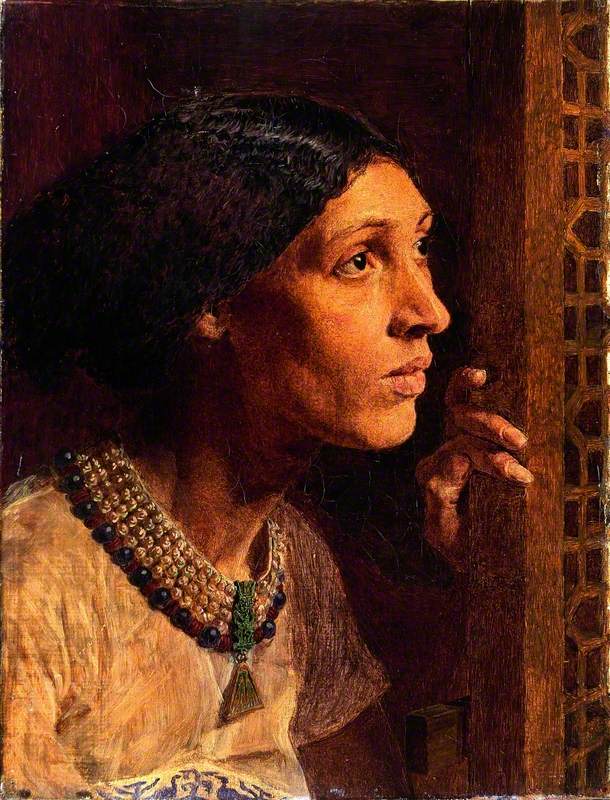

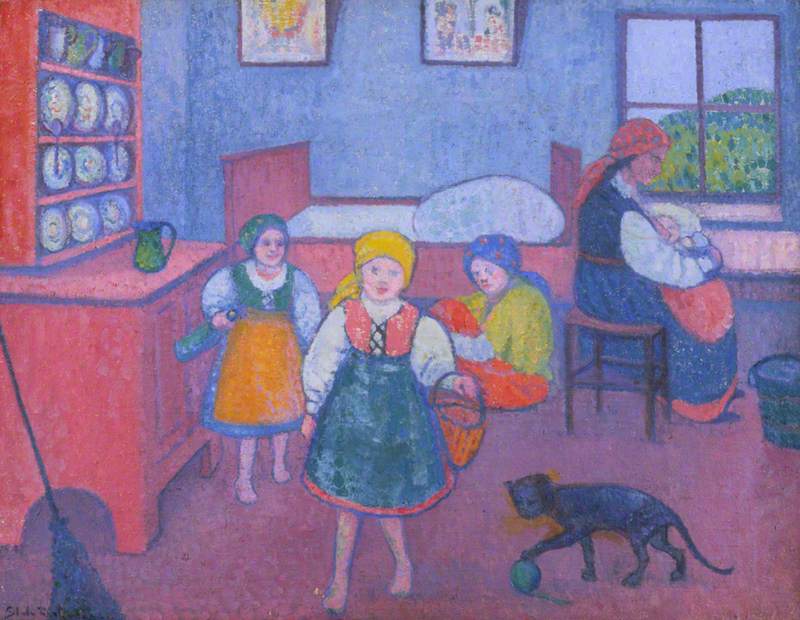

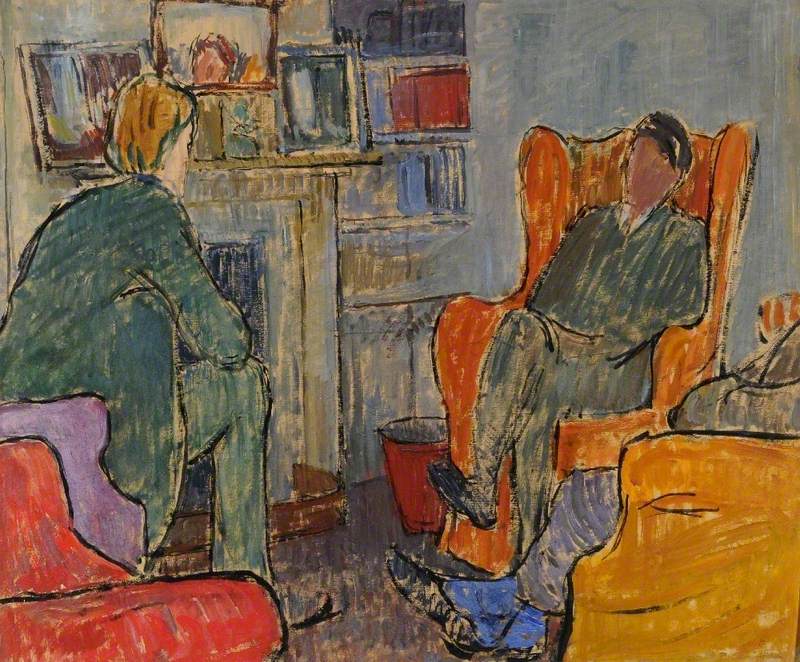

A later interest of Sickert's was nudes, again inspired by Degas and also Pierre Bonnard. These were considered immoral in Britain, thanks to their subjects' unidealised bodies, often depicted in a contemporary and dingy setting. Presented from voyeuristic viewpoints, suggestive of poverty and prostitution – the iron bedstead was a recurring symbol of seedy Camden Town where the artist was based for much of this time.

Conversely, these were admired in France where they were first exhibited in 1905, six years before they were shown in London. These unromantic depictions, focusing on bare flesh, can be seen as prefiguring the concerns of followers such as Lucian Freud.

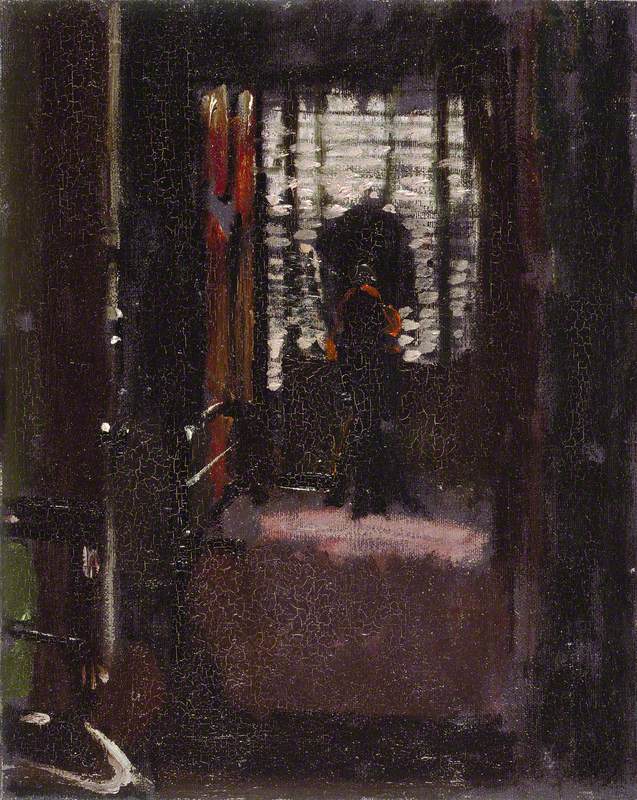

Sickert went further, though, in hinting at narratives for some nudes, such as The Camden Town Murder, where two figures meet in a claustrophobic interior, a much more sensationalist title than its alternative, What Shall We Do for the Rent? The fact that a work could have such wildly different monikers suggests this was little more than an afterthought or that any clues provided should not be taken too literally.

Nevertheless, this subject matter leads to the thorny issue of the artist's relationship with the most notorious killings in Victorian London – the 1888 murders attributed to Jack the Ripper. Books and TV programmes accusing Sickert of being a potential suspect date back to the 1970s. While it seems the artist was actually in France when most of the murders took place, those such as the crime writer Patricia Cornwell still build their cases. Certainly, there is ample evidence that Sickert was obsessed with the crimes.

The space depicted in Jack The Ripper's Bedroom (1906–1907) was in fact in Sickert's own lodgings at 6 Mornington Crescent, London. His landlady had apparently told the painter she suspected the previous tenant of being the murderer. Contemporary acquaintances such as Max Beerbohm and Osbert Sitwell meanwhile attest to the artist's long-term fascination. Furthermore, thanks to research instigated by Tate, a handful of hoax letters purported to have been sent to the press by Jack have been reliably linked to Sickert.

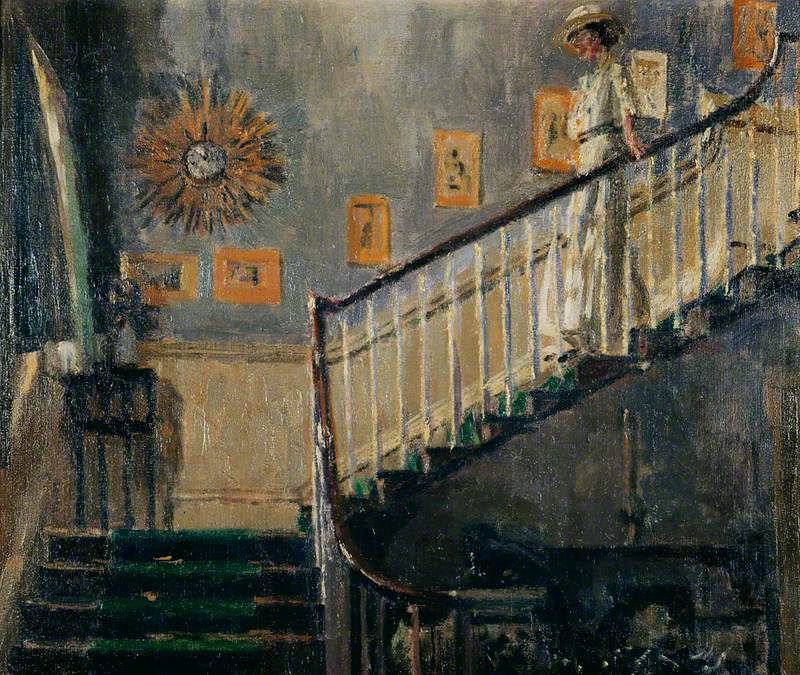

In reality, though, Sickert was keen that painting applied to everyday, domestic scenes, sometimes with downbeat atmospheres that hinted at the conflicted emotions of modern relationships. For works such as Ennui (1917–1918), he actually drew on the real-life character of Hubby, an old school friend that had fallen into poverty and whom Sickert provided with beer.

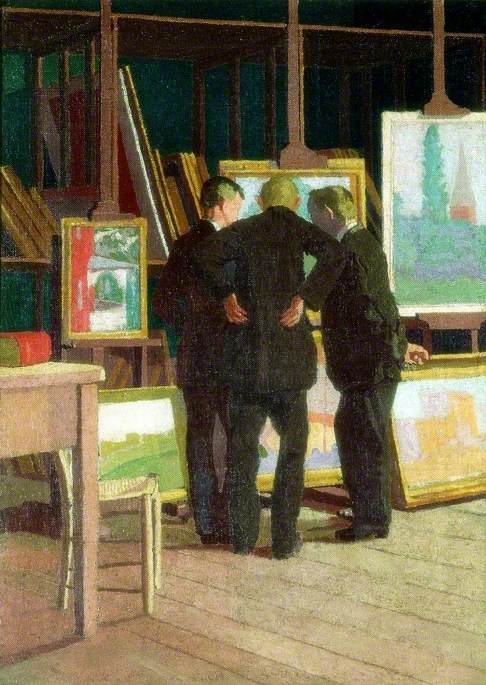

While polite society criticised these concerns in the everyday, Sickert proved an influential conduit in Britain for the avant-garde ideas and subject matters emerging in France. On his return to England in 1905, he inspired a younger generation through his work and charisma.

Known for his wit and charm, Sickert was also famed for his teaching and writing on art. Figures from his circle founded some of the most influential art groups in the capital – the Allied Artists' Association, the London Group and the Camden Town Group, featuring the likes of Spencer Gore and Harold Gilman, all interested in following the developments of Post-Impressionism.

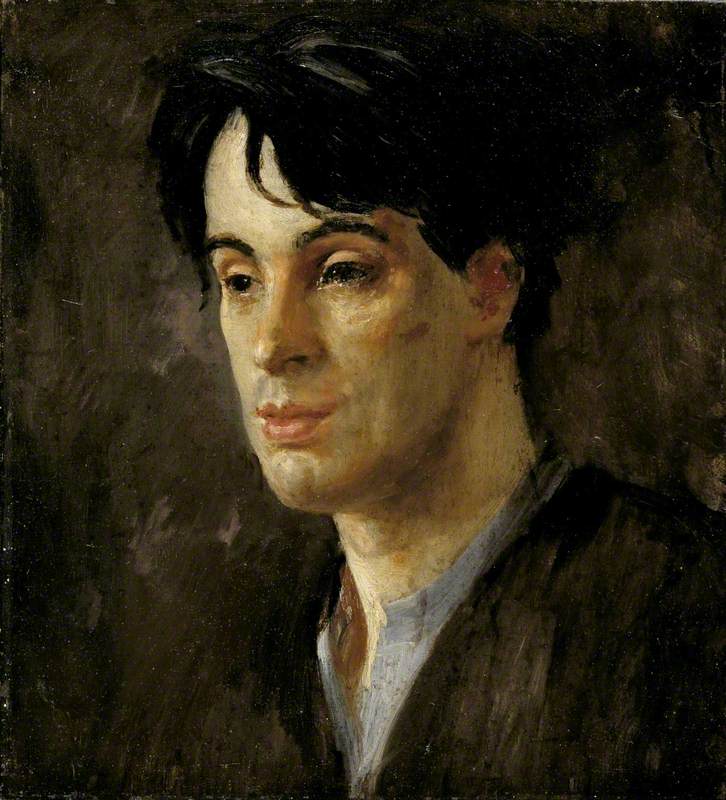

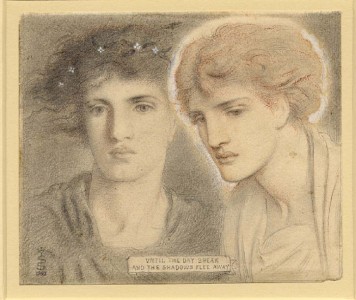

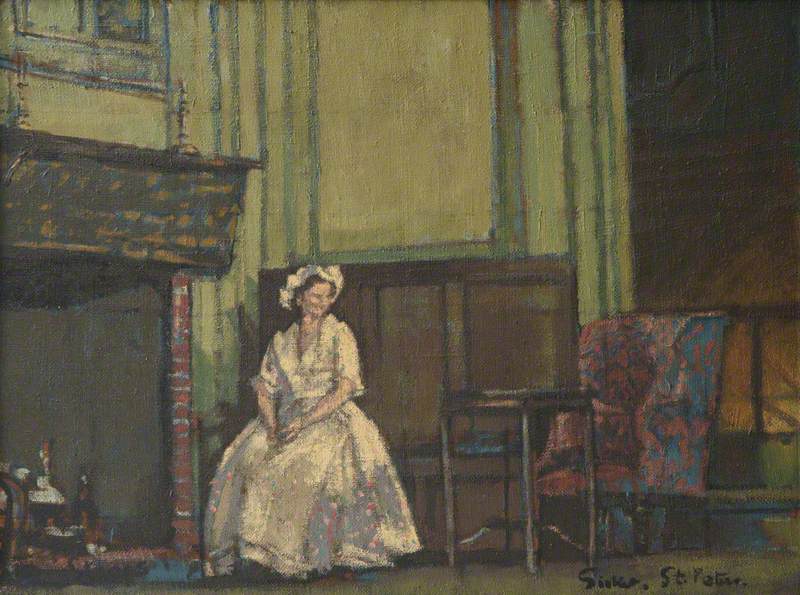

Image credit: University of Bristol Theatre Collection

Peggy Ashcroft as Miss Hardcastle c.1933

Walter Richard Sickert (1860–1942)

University of Bristol Theatre CollectionIn his final years, Sickert explored larger, brighter works based on artefacts from popular culture, including news photographs and Victorian illustrations. He had used photography as source material since the 1890s – another technique he could have absorbed from Degas – though during the 1930s this became more routine. Subjects included Amelia Earhart's solo flight across the Atlantic and an interest in the career of classical actress Peggy Ashcroft (here she stars in the comedy She Stoops to Conquer).

While a loose handling of paint and an expressionist disregard for detail gave Sickert's work added immediacy, it is his reliance on photography for inspiration that suggests he was a precursor both to Francis Bacon's use of similar sources of imagery and to Pop Art's transformation of mass media.

On his return to England, Sickert lived in London and Brighton before moving to Broadstairs, Kent, in 1934 and finally to Bathampton, Somerset, four years later, where he died in 1942. Since then, he has always been regarded as having been at the forefront of the development of British art. Even his later period, previously dismissed by pundits as one of decline, has been reappraised as important work.

Sickert's influence, though, is best described in his own words, which answered most of his critics' complaints: the catalogue for Tate Britain's current exhibition quotes from his writing: 'The plastic arts are gross arts, dealing joyously with gross material facts... and while they will flourish in the scullery, or on the dunghill, they fade at a breath from the drawing room.'

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Walter Sickert' at Tate Britain runs until 18th September 2022

You can buy a range of Sickert's works as prints on the Art UK Shop