In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

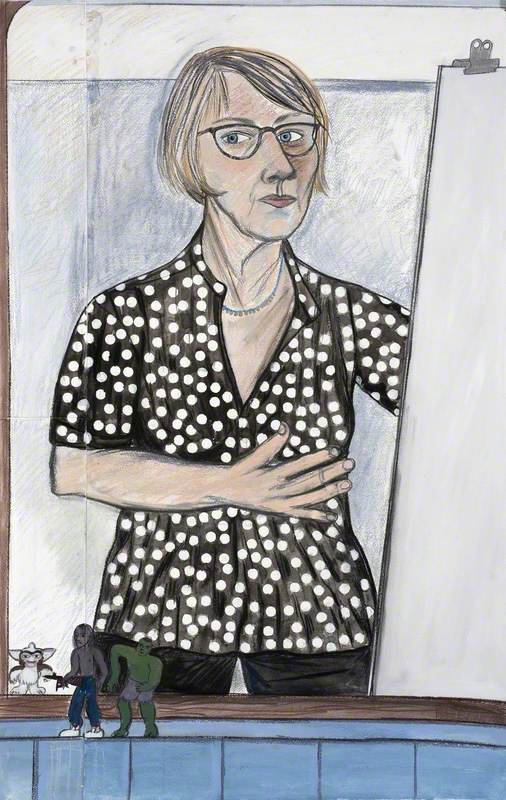

The paintings of Scottish artist Caroline Walker meditate on women's work, or at least, the kind of work that is often overlooked or wrongly devalued by society. From hotel cleaners to the domestic chores of her mother, Walker shifts the gaze towards the often invisible, everyday labour of many women across the country. Seductive, atmospheric and ostensibly contemporary in subject matter, her paintings nevertheless maintain the realist traditions of the medium. Loose and visible brushwork recalls some of her artistic influences from history – going as far back as Édouard Manet or Mary Cassatt.

In anticipation of her upcoming show at The Fitzrovia Chapel, 'Caroline Walker: Birth Reflections' – which will present a new body of work following her residency at the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (the maternity wing) at University College London Hospitals (UCLH) – Art UK speaks to the artist.

Caroline Walker, 2018

Lydia, Art UK: Your work has consistently captured the interior lives of women, whether women's physical space at home or at work, or simply their private and intimate moments with themselves. How and why do you think this fascination began?

Caroline Walker: It's difficult to say. Some of it just seemed to be hardwired. From a very early age, I would draw obsessively and all I wanted to make were pictures of women. I remember being fascinated by what I referred to as 'fancy ladies' in magazines and mail-order catalogues, especially if they were wearing high heels and glamorous clothes.

But I think the environment of home had the biggest influence on me. My parents took very traditional, gendered roles – my Dad went out to work and then spent the weekends doing building projects on the house, while my Mum took the role of the homemaker – cooking, cleaning and looking after me and my brother. So my Mum was a very strong presence in my life and a role model. I questioned this division of labour though from a very early age and was always asking annoying questions about why Mum (i.e. all women) had to do some jobs that Dad (all men) never seemed to do. And the images of women I was looking at in magazines seemed far away from the reality of my Mum's day-to-day life. I was both delighted to have my Mum at home all the time and quite adamant that that wasn't what I would do when I grew up. I think it was this early questioning about the roles of women and that conflict between career and home that sparked a fascination that's continued in my work as an artist.

Lydia: One of your earlier series from 2009, 'St Pauls Road' chronicles the daily activities of an anonymous female figure. Can you tell us more about this body of work?

Caroline: I made this series while I was studying at the Royal College of Art. I met a model called Liat at a life drawing class and really enjoyed drawing her, so we started working together. She didn't have a permanent home at the time, so would move around different people's houses dog and cat sitting. I would go and visit her at each of these houses, where I would draw, paint and photograph her. It resulted in a series of paintings where she was this constant subject, but the backdrop kept changing. It made me realise how this could change what we imagined the narrative to be. I also found it interesting that she was not 'at home' in any of these places, so I think there was an inherent awkwardness about her in those spaces. It started me on a path over the next seven or eight years of pulling apart different elements of the way I was making paintings, from this starting point of location, to lighting, colour, characters and props.

Lydia: You use photography to aid with the composition of your scenes, but you also spend time with your subjects, so that the work is infused with your experience of getting to know these women – how do you obtain this delicate balance between objective and the subjective in your work?

Caroline: It's hard to pinpoint how this combination of photography and memory comes together in the resulting paintings, but it's vital that the photography is my own, that it's a document of the time I've spent in a space, and the way I saw it. I think perhaps memory starts to become an important part of the process when I'm in the studio and assessing the photographic material that I have. I find myself drawn to the images that resonate with my spatial memory of the place or capture something about how I remember particular people or the atmosphere. My photographs are often not totally accurate in terms of colour and lighting so it's then the job of my memory to fill in the gaps or adjust things. I find that lighting that can often be a very strong factor in that memory – for example, if it's harsh strip lighting, bright sunlight or the contrast of twilight and lighted interiors.

Lydia: Works such as Conditioning (2019) in the National Museum Cardiff remind me of Dutch painting or 'toilette' scenes – perhaps the interiors of Vermeer or Gerrit Dou. To what extent do art historical references shape and inform your work?

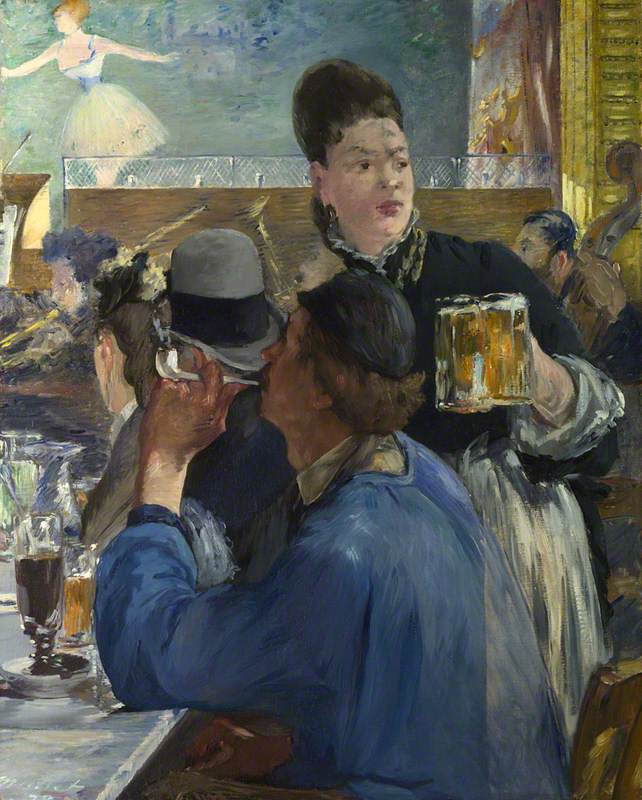

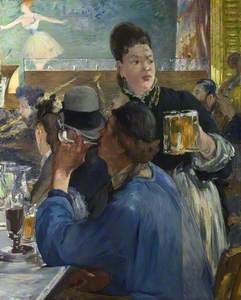

Caroline: Western art history is a significant reference in my work and its historical artworks that I return to again and again for inspiration, particularly Dutch genre painting, as you mention, and also late nineteenth-century French painters such as Manet, Dégas and Cassatt.

I think rather than referencing specific paintings though, I tend to think of the compositional elements or recurring subject motifs that run as a thread through particular periods of art history. What I admire in both Dutch genre painting and those nineteenth-century French painters is that the work reflects so directly on the times and society in which it was made. That's how I try to think about the work I make – I want it to be about what it is to be alive, in this moment.

Lydia: In 2018, you worked on a series in collaboration with the charity Women for Refugee Women and Kettle's Yard, Cambridge, when you created Joy, 11am, Hackney. Can you tell us how you navigated this project and what it was like to closely observe the everyday experiences of asylum seekers?

Caroline: Kettle's Yard asked me to make a series of work in response to the refugee crisis in autumn 2016, but it was another six months of thinking about how and if I should take this on as a subject before the project started to take shape. I knew I had to approach it in a very different way to any previous work, which for years had been the result of staged photoshoots which were driven by a narrative of my invention. I knew from the outset that this project needed to take the lead from the people who would be the subject of it.

The collaboration with Women for Refugee Women took the form of portraits of five women in their network that wanted to work with me. I started by making visits to these women in the accommodation that they had at that time (summer 2017). I was quite nervous before starting though as I hadn't met most of the women before or seen where they were living, so I had no idea what to expect visually and, in turn, how or what form my artistic response would take. This was so different to how I was used to working, where I had complete visual control. I had to use all the skills I'd developed over years of creating narrative in my paintings, but in reverse – I was entering someone's story and looking for the clues to its telling.

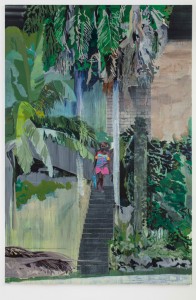

Tarh, 10.30am, Southall

2017, oil on linen by Caroline Walker (b.1982)

The women I worked with all had very different circumstances, were from different countries, and had come here for different reasons. But the overwhelming sense I got from all of them was of being in limbo, unable to move forward with their lives because they faced such uncertainty in their day-to-day living and their future. I wanted to try and capture some of that feeling in the paintings but in a quiet way, the opposite of the headline-grabbing drama of the media's representation of the experience of refugees. I wanted the paintings to be about the everyday, and the banality or boredom of time spent in this kind of limbo. I asked the women just to do what they'd be doing normally, or we chatted about how they felt about where they were living. I wanted them to be in control of how they would be presented as much as possible.

When I started the project, I was anxious about making 'portraits' in any kind of traditional sense, because that wasn't what I did, and I thought that being very specific would stop the paintings being universal. I completely changed my mind though once I'd made them. I'd spent years travelling to the other side of the world to invent stories in my paintings, but this project made me realise that real people's lives are far more interesting and complex. Joy was only living a ten-minute walk away from my studio and it made me think about invisibility and how there are all these lives around us in the city that we don't know about. That had a huge influence on me and really transformed my working methods. The starting point for all my work now is real women's lives.

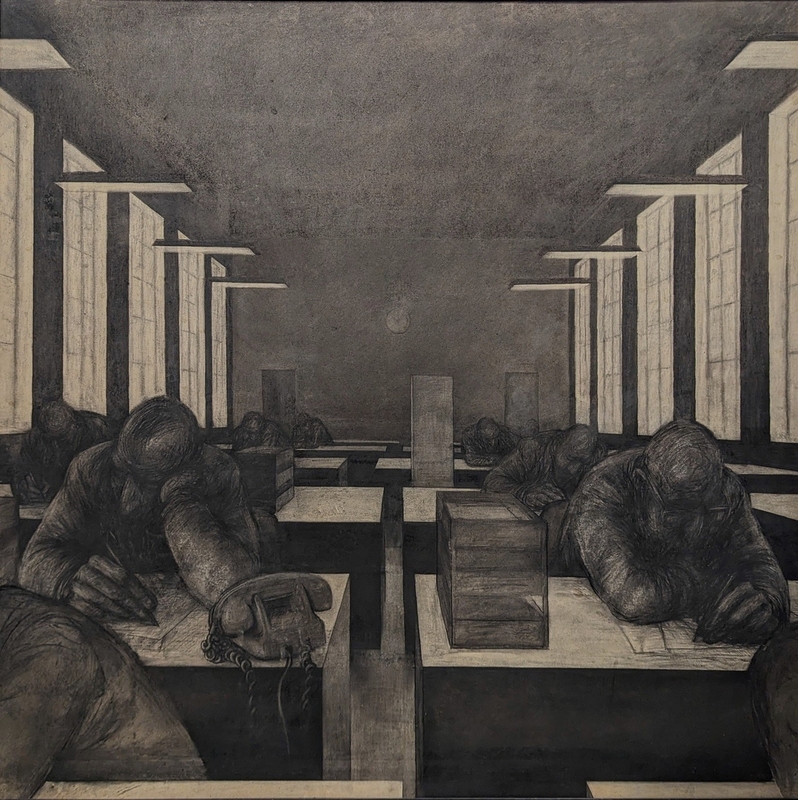

Corridor, 3rd Floor

2018, oil on linen by Caroline Walker (b.1982)

Lydia: Between 2019 and 2020 you created a series about your mother, highlighting the time and labour that goes into the maintenance of the home. In this sense, your work recalls the lineage of women who have given visibility to the unpaid labour of women in the home, I'm thinking of the 'maintenance' work of artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles, or the Italian feminist group, Wages for Housework. Did you spend a lot of time thinking about these kinds of issues whilst observing and painting your mother?

Caroline: Yes definitely. The idea to make my Mum and her home life a subject for my work came out of a conversation with her about the unpaid labour of housework and its place as 'women's work'. In 2018 I was working on a series of paintings about women in hotel housekeeping and I'd spent a couple of mornings shadowing women working in London hotels. I was really struck by both the hard physical nature of their work – cleaning rooms at speed – also the very repetitive and boring aspect of doing the same task repeatedly in identical rooms: changing 20 beds, cleaning 20 bathrooms, mopping 20 floors.

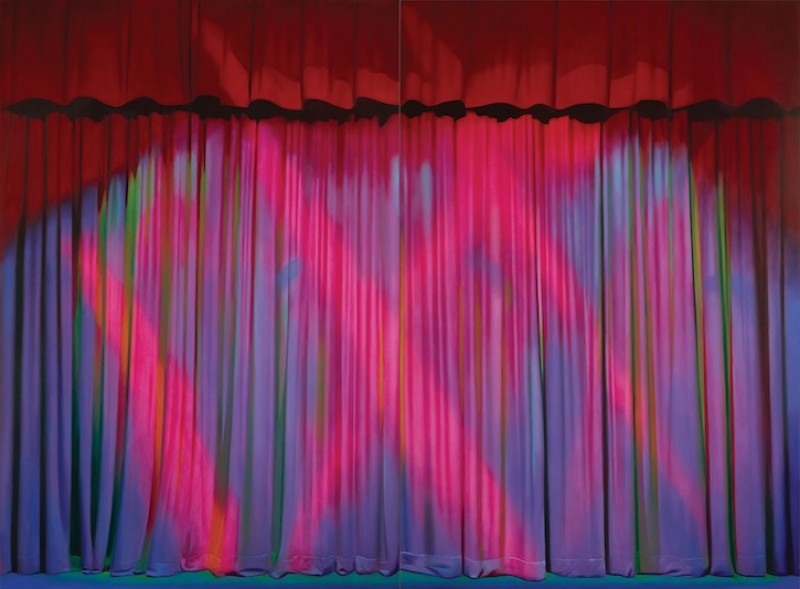

Changing Pillowcases, Mid Morning, March

2020, oil on linen by Caroline Walker (b.1982)

I was talking to my Mum about this, and she reminded me that her Mum and Gran had been cleaners, mainly cleaning houses in Edinburgh. We discussed how women would go out to these paid cleaning jobs but would then inevitably go home and get to work on the unpaid job of cleaning their own homes. My Mum was reflecting on how, through education and social mobility, she hadn't had to clean anyone's house for money, but had instead spent the last four decades cleaning her own for nothing.

It made me think a lot about this undervalued and largely unseen work that is done in the home, overwhelmingly by women. I'd been thinking about this in various ways since I was a child, observing my Mum forever busy, and it seemed like the right time to make it the subject of my work, to recognise and celebrate it.

Lydia: Your upcoming show 'Birth Reflections' at The Fitzrovia Chapel reflects your residency at UCLH and adds a new dimension to observations about women's work, or life experiences. The series coincided with your own pregnancy (congratulations!). How did this personal journey entwine with your artistic one?

Caroline: I'd started speaking to UCLH about a residency in the hospital in spring 2019 but wasn't sure yet where I wanted to focus my attentions. It wasn't until I got pregnant and started visiting the hospital for appointments as an expectant mother that I began to become very interested in the maternity wing. There are a lot of different things going on there, which makes it visually interesting, but also, it's such a women-centred part of the hospital – the patients are women but the workforce is also largely women, as midwifery and nursing are so female-dominated. As the pregnancy progressed it seemed like the obvious choice for my residency in the hospital.

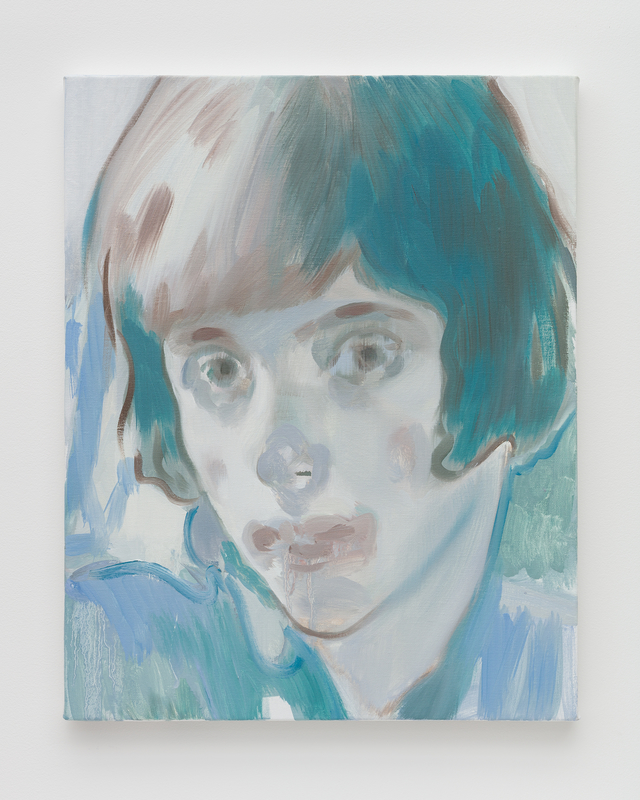

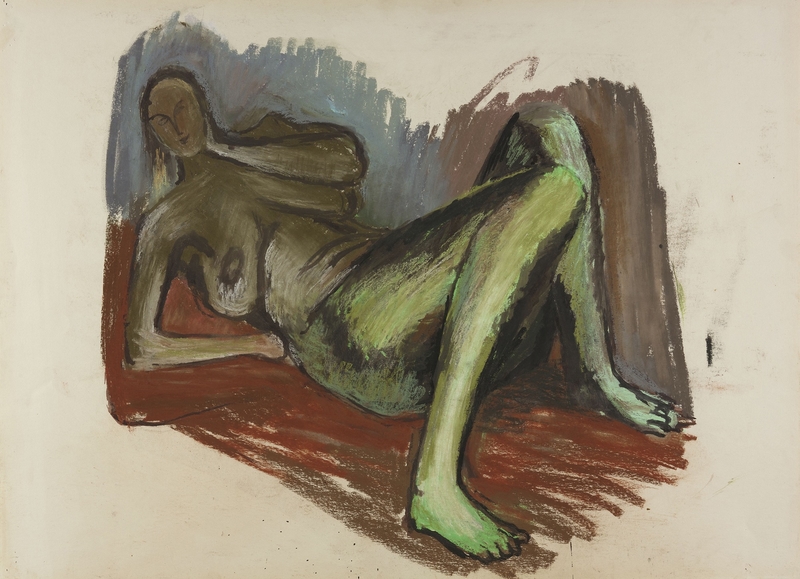

Study for 'Ultrasound'

2021, oil on paper by Caroline Walker (b.1982)

I didn't have a great birth experience, which I know is not uncommon. As a result, though I was nervous about returning to the hospital – it was over a year later than had been planned, because of Covid – I found it strangely cathartic, as I felt much more confident in my role as an artist than I had as a new mother, and it highlighted to me how much our experience of space can be intertwined with our emotional state so that memory is not necessarily the most reliable record.

Distances that had seemed enormous to me when I was struggling to move around, post-birth, were only a few metres. I think mixing the personal and subjective experience of place with the observational or documentary view of women's working lives that I'm known for, has led to a unique body of work that is infused with those different roles women are balancing all the time, and which I'm trying to figure out through the act of painting.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Birth Reflections' at The Fitzrovia Chapel will run between 18th February and 4th March 2022