Paintings of cattle are ubiquitous on Art UK. Dutch artists working during the so-called Golden Age paved the way for this distinct genre of landscape painting. Writing in Het Schilder-Boeck (1604), an artists' guide to painting, Flemish painter and art historian Karel van Mander commends bulls, oxen and cows as beautiful and graceful subjects for painting, best observed from life 'grazing on the green'. Many Dutch artists went on to specialise in this field. But why were cows and bulls rampant in the Dutch imagination?

The political significance of cattle dates back to the birth of the Dutch Republic in 1581, when seven provinces of the Netherlands united to fight against Spanish rule. Paintings and prints from the 1580s feature cows as a symbol of Dutch identity, as well as a vital landed asset to be protected during the Eighty Years' War that followed unification.

A satirical painting by an unknown artist from around 1586 shows key European players flocking around a Dutch cow, poking fun at those who undermined Dutch independence. Elizabeth I feeds the cow, while the leader of the Dutch revolt, William of Orange, holds it steady by the horns. Philip II attempts to ride it, drawing blood, while the Duke of Anjou (responsible for a failed coup against Antwerp in 1583) is pooed on. The venturesome Earl of Leicester, the governor-general of the United Provinces from 1585–1587, milks the cow.

Image credit: public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Queen Elizabeth I Feeds the Dutch Cow

c.1586, oil on panel by unknown artist

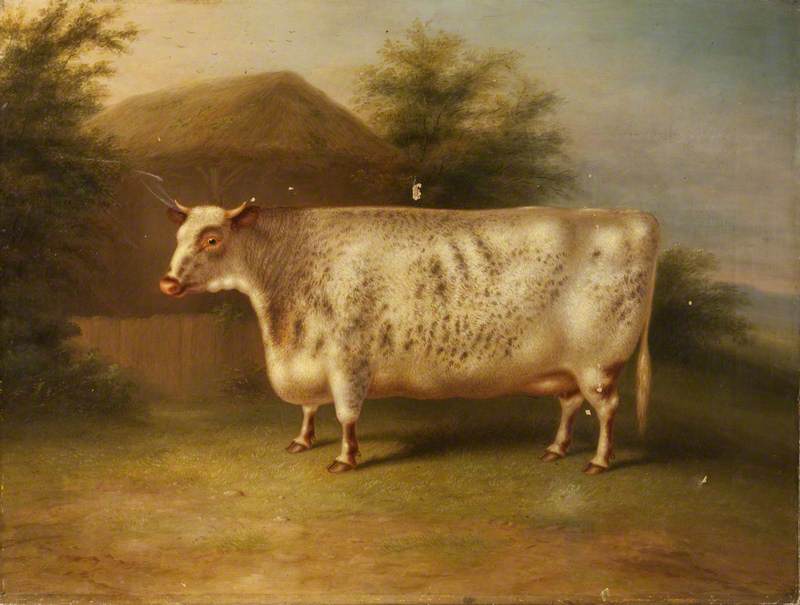

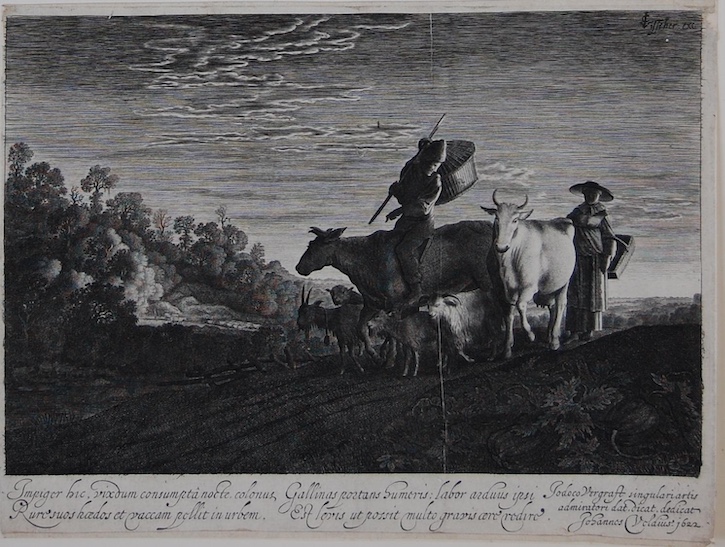

An early print, The White Cow (1622) by Haarlem artist Jan van de Velde II (c.1593–1641), is explicit about the economic status of cows. A horned cow is illuminated in sharp contrast to the farmer, shepherdess and goats who are silhouetted in shadow. The accompanying inscription reads: 'The night is hardly gone before this industrious countryman drives his goats and a cow from the country to the town...The heavy work is light for him as long as he comes home loaded down with much money.' The balance of light and dark in the etching supports a clear message: cows were prized possessions for farmers because they were profitable.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

The white cow

1622, engraving on paper by Jan van de Velde II (c.1593–1641)

After unification, the Dutch Republic's merchant navy was a leading player in global trade. High imports of grain allowed farmers to focus their efforts on animal husbandry and the meat trade. The Dutch pioneered new farming methods, including the four-crop rotation system, which resulted in higher yields and more feed for cattle. Efforts to improve land and transportation, particularly closer to coastal areas, also supported the cattle industry.

The grazing cows in A Landscape with Cottages (1646) are not incidental. The building of canals and towpaths between cities in the seventeenth century (trekvaarten), and the enclosure of land, supported the trading of meat, dairy and livestock.

Image credit: National Trust Images

A Landscape with Cottages 1646

Emanuel Murant (1622–1700) (attributed to)

National Trust, Upton HouseThe dairy industry contributed to a rich and varied Dutch diet, and high consumption of butter (over lard) was seen as a sign of wellbeing by European neighbours. Meat, butter and cheese were sold as expensive exports too. In his epic poem, Hertspiegel (1614), Dutch writer and philosopher Hendrik Laurenszoon Spiegel celebrated spring as a time when cattle, 'full of milk', are sent to 'fresh pastures' and ice melts 'to fat and butter'.

The Milkmaid (1646), by the forefather of animal painting, Paulus Potter (1625–1654), celebrates Dutch dairy farming. Painted on a grand scale, the cattle, sheep and milkmaid are elevated using a low viewpoint. The milkmaid is shown with disproportionately large hands, indicating her strength for the task of milking. The horned cow on the left gazes out at the viewer with a slightly open mouth, as though smiling, and Potter renders the textures of the animals' coats of matted hair and wool in incredible detail. A rugged tree trunk on the left frames the picture, giving it a theatrical quality.

The same dramatic device is used in Potter's famous painting, The Bull (1647), held at the Mauritshuis. Here a young bull dominates the canvas, his playful expression mirroring that of the stocky farmer standing to the left. Young bullocks had an important role in Dutch farming. They were sold at the age of two or three to be fattened on the best pastures around towns, and then sold on for slaughter. Potter was masterful at bringing out the personalities of animals, and he was one of the first Dutch artists to focus on changing and inclement weather. Man and beast are unfazed by dark storm clouds on the horizon.

Image credit: Mauritshuis, The Hague

The Bull

1647, oil on canvas by Paulus Potter (1625–1654)

Potter's bulls and cows celebrate animals and Dutch prosperity, but also Dutch resilience. His paintings coincided with the end of the Eighty Years' War against Spain and the consolidation of Dutch land. From around 1570–1648, land and livestock were periodically ransacked and plundered during the battles of the Revolt. War with the Spanish threatened a trajectory of growth. The Peace of Münster in 1648 ended the threat, in a deal recognising the Dutch Republic's right to exist. Characterful and tranquil cattle scenes that followed the Peace celebrated more stable times.

Adriaen van de Velde (1636–1672) was influenced by Potter, and pastures with cattle and herders predominate his work of 1653–1658. In A Farm with a Dead Tree (1658) – a typically expansive scene incorporating many vignettes – a distinctive grey-horned bull is shown on the right. It is possible that the stark, dead tree in the centre references the darker story of Dutch independence. However, the tree is softened with foliage growing around it, and Van de Velde places a milkmaid milking a cow at its base. They are bathed in sunlight and cattle grazing on a plain are visible in the background. There is a sense that what is past is past.

Many other Dutch artists specialised in cattle painting, one of the most celebrated being Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691). Cuyp's clientele were wealthy traders living in his hometown of Dordrecht, who had landed property in the vicinity. A Herdsman with Five Cows (c.1650–1655) is characteristic of his back-lit and side-lit landscapes, low horizons, drifting fluffy clouds, soft lighting and earthy colours. Here Cuyp paints the cattle on a similar scale to Potter. Compositionally, they are given equal weight to the local river (the Maas or Waal), which carries fishermen and ships – other signs of Dutch wealth.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

A Herdsman with Five Cows by a River about 1650-5

Aelbert Cuyp (1620–1691)

The National Gallery, LondonIn The Avenue at Meerdervoort (early 1650s), cattle relax and roam freely on a distinctive tree-lined avenue, distracting the horsemen and a group of women and children. The church tower and windmills of Dordrecht dominate the skyline on the right, emphasising the Dutch Republic's affiliation with Protestantism, as well as signalling their work pumping water from low-lying plains into rivers. Drainage projects made more land usable for cattle and dairy farming.

Nicolaes Berchem (1620–1683) and Karel Dujardin (1626–1678) were among a group of artists who combined cattle painting with contemporary Italian scenery and buildings. It is not clear whether either artist travelled to Italy, but many Dutch artists did travel there as part of their artistic training in the seventeenth century. In Pastoral Landscape (probably 1650s), which features Italian mountains, Dujardin places the viewer below the horse and the fattened bull, while two boys sit together and relax alongside the animals.

In A Woman with Cattle and Sheep (1650–1655), a Dutch worker sits happily spinning wool alongside livestock, either side of an Italian farm building in the distance. The standing cow is shown with its back to the viewer, adding a sense of spontaneity and realism, but its horns and bulk are powerfully outlined against the sunlit sky. Dujardin's compositions are carefully balanced, giving equal weight to people and animals, who are shown at ease with one another.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

A Woman with Cattle and Sheep in an Italian Landscape 1650-5

Karel Dujardin (1626–1678)

The National Gallery, LondonBerchem also combined elements of genre painting with landscape painting, and featured cattle frequently in paintings calculated to please and reassure Dutch and Italian clientele. In A Peasant playing a Hurdy-Gurdy (1658), Berchem draws upon older images of the Madonna and Child to frame a vignette of a countrywoman cradling her infant near a large, brown ox. This gentle giant mirrors her repose and is painted with the same warmth and depth of colour.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Nicolaes Pietersz Berchem (1620–1683)

The National Gallery, LondonPerhaps the most striking idealised Dutch painting showing the interaction of humans and animals with the landscape is Canal Landscape with Figures Bathing (1675) by Hendrick ten Oever (1639–1716). It shows the sun setting on a glorious summer's evening over a canal on course to the artist's birthplace, Zwolle, and an expanse of bright, verdant grassland. The knowing cattle, canal, flat plain and city skyline are now familiar hallmarks of Dutch patriotism, but the inclusion of nude figures striking a variety of Classical poses was unusual.

Scenes of bovine bliss contrast with the state of livestock farming in the Netherlands today. The intensity of cattle farming has prompted the European Union to issue a directive aimed at tackling high nitrogen emissions and associated environmental costs. A large-scale farmers' revolt in 2019, bearing slogans such as 'how dairy you', and ongoing resistance to the closing and purchase of farms suggests that cattle remain crucial to the Dutch psyche.

Rachel Bates, freelance writer

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Jan Bieleman, Five centuries of farming: A short history of Dutch agriculture 1500–2000, Wageningen Academic Publishers, 2010

Jan Bieleman, 'Rural Change in the Dutch Province of Drenthe', in Agricultural History Review 33, 1983

Christopher Brown et al., Dutch Landscape: The Early Years, National Gallery, 1986

Jaap Harskamp, 'The Low Countries and the English Agricultural Revolution', in Gastromonica, vol. 9, no. 3, 2009

Karen Hearn, Dynasties: Painting in Tudor and Jacobean England, Tate Publishing, 1995