There's a point in late December when your liver may well be considering taking out a restraining order on the rest of you, it's become acceptable to drink bucks fizz for breakfast, and around 78% of the liquid you consume appears to be mulled. And just around the corner is an annual excuse for bacchanalian levels of excess. As New Year's Eve rears its head and with a potential 'Dry January' just around the corner, we thought it was time to take a look at the history of alcohol and art, and the relationship between the two.

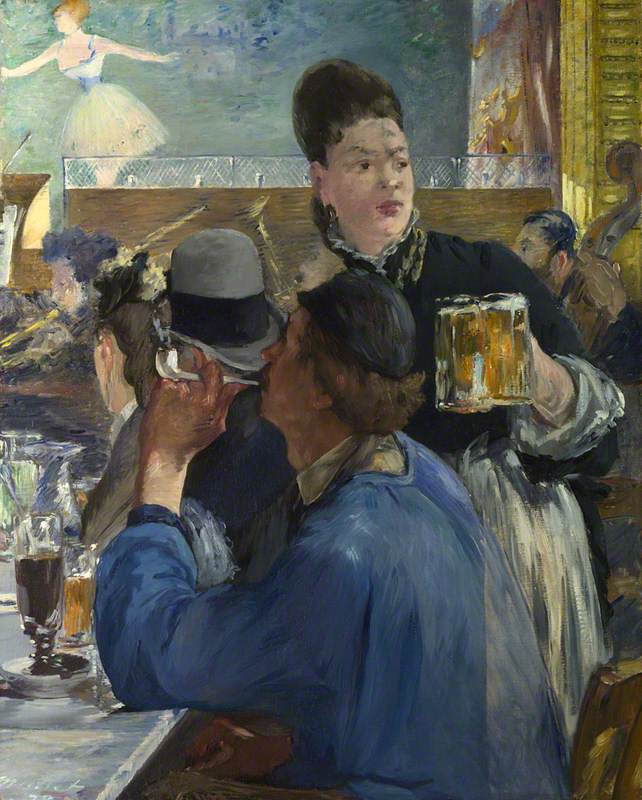

Alcohol – and its effects on those who consume it – has fascinated generations of artists. From Diego Velázquez's The Feast of Bacchus, (a copy of which is on Art UK) where the deity is depicted offering wine as a gift to mankind, to William Hogarth's (in)famous Gin Lane, powerfully decrying the evils of spirit consumption, art has served as both a celebration and critique of the power of intoxication.

We've taken a small selection of boozy works from Art UK.

There are any number of depictions of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, in art: Nicolas Poussin's A Bacchanalian Revel before a Term is a wonderful example, making debauchery look beautiful. In his Roman incarnation, Dionysus was known as Bacchus – hence the term 'bacchanalian' – and again, has been depicted in hundreds of paintings.

Drunken Silenus supported by Satyrs

about 1620

Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) (attributed to)

Drunken Silenus Supported by Satyrs, attributed to Anthony van Dyck (and thought to be from the studio of Rubens), instead shows us Silenus – Dionysus' companion – an old, drunken man who needs the support of satyrs to stay upright. His intoxication is shown as a state of collapse and loss of function: a kind of harmless, inoffensive inebriation. You can also spot Silenus here in Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne, at the back of the painting on the right, slumped over a donkey.

Dutch artist Jan Steen was fascinated by the goings-on in the booze house, and inserted himself into many of his paintings, here portraying himself as one of the drinkers in the scene (lifting the woman's skirt).

The Interior of an Inn ('The Broken Eggs')

about 1665-70

Jan Steen (1625/1626–1679)

Where other artists used mythology to comment on reality, Steen's work was grounded firmly in the real world, depicting people in all of their crass, drunken antics. The moral message here is ambiguous – is this just a humorous depiction of events, or is it meant as a warning against immoral behaviour?

George Cruikshank was renowned for his searing caricatures of English life – to the extent that he was offered money by George IV so that he wouldn't satirise the king. So this moralistic piece, depicting the negative consequences of drinking played out on a grand scale, is atypically serious for the artist.

Cruikshank's own father died in a drinking contest, and this colossal exposure of society's nasty underbelly was described by the artist as 'a mapping out of certain ideas for an especial purpose' – as a lesson, and a warning against the perils of intoxication. The grand scale of the piece attests to Cruikshank's earnestness in getting his message across.

Another painting with a moral message, we see here Robert Braithwaite Martineau telling the story of a family home lost to irresponsible behaviour driven by alcohol.

It's a bleak take on drink, with the young boy on the right hand side raising his glass and cementing a future following in his father's footsteps – a father who is remarkably unconcerned about having just gambled his home away.

An exploration of alcohol and art wouldn't be complete without discussing absinthe: the 'green fairy' that was both the fuel and the subject for a group of artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century, to the extent that five o'clock in Paris became known as the 'green hour'.

A perfect storm of circumstances led to this brief triumph of absinthe over wine as France's national drink of choice. Firstly, in the 1830s, French troops fighting in Algeria used absinthe as an anti-malarial, and when they returned home brought their new taste for the drink with them, making it popular among the Parisian middle classes.

Secondly, the insect phylloxera devastated vineyards in the 1870s, meaning any wine still being produced was too expensive for the poor, whereas absinthe could be made cheaply with the use of industrial alcohol.

Jad Adams, author of Hideous Absinthe: History of the Devil in a Bottle told the BBC in 2011 – just as sale of absinthe was about to become legal again in France – that 'it was cheap, it was an industrial alcohol, and it was very easy to buy... it was the drink of the poor, and if you were a poor artist, like Vincent van Gogh, you were going to take the cheapest kind of alcohol you could.'

Another famous partaker of la fée verte was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who illustrated the life of people in music halls, bars, brothels and the famous Moulin Rouge – all while (apparently) carrying a hollow walking stick which contained a draught of the green fairy for himself.

Jane Avril in the Entrance to the Moulin Rouge, Putting on her Gloves

c.1892

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

Even artists who weren't under the thrall of the green fairy themselves were fascinated by the 'absinthemania' that had taken over society. Edgar Degas made a number of studies of the people who frequented cafes for absinthe, and his most famous – originally titled Dans un Cafe but later re-titled L'Absinthe – was hissed at by crowds at Christie's when it came up for auction in 1892, eventually selling for £180. Another of his studies, At the Cafe, is on Art UK, the two figures, one grey-faced, engaged in despairing discussion.

Absinthe was widely banned in Europe and isn't often drunk in its original, powerful green form any more. Yet alcohol as a subject has been re-imagined and re-examined by a generation of contemporary artists. Tate Britain's 2015–2016 display Art and Alcohol brings us up to date – Gilbert and George's Balls: The Evening before the Morning After – Drinking Sculpture – a series of contemporary photographs designed to evoke the disjointed experience of an evening spent in the pub – hangs opposite Cruikshank's The Worship of Bacchus.

There's still time to visit Art and Alcohol at London's @Tate Britain. > https://t.co/LHY866cwru pic.twitter.com/Ek5Mmw0lca

— FredPerrySubculture (@FredPerry_Sub) August 18, 2016

Perhaps alcohol and creativity will always be linked in the popular imagination. For all that Degas and his contemporaries painted dead-eyed absinthe drinkers in a decidedly unromanticised fashion, there's a pervasive idea of the tortured artist – the person who spends their life drinking but who also produces works of startling genius. It's an idea that extends beyond the visual arts, into literature and music, and it's somehow never a surprise to hear that towering artistic figures of the past were big drinkers. It's easy to conjure up an image of Hemingway, sat at his typewriter, simultaneously creating Death in the Afternoon – the book – and Death in the Afternoon – the cocktail.

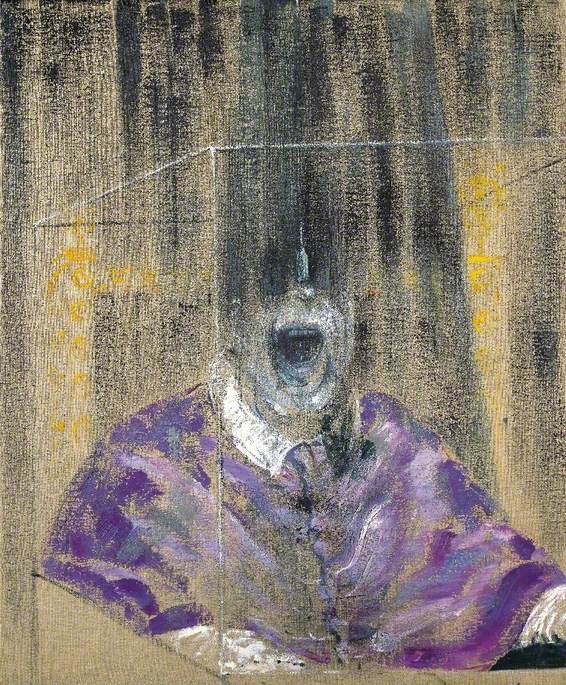

Francis Bacon, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Pablo Picasso, Maurice Utrillo, Jackson Pollock: all were known for their drinking habits as well as their artistic achievements. As Daniel Farson wrote of his friend Francis Bacon:

'He would wave his bottle of champagne, slopping it into the glasses of those around him, spilling much of it on the floor, with the Edwardian toast: "Real pain for your sham friends, champagne for your real friends"... He told me that drink and the after-effects forced him to concentrate on his painting and at times it gave him "a sort of freedom".'

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer