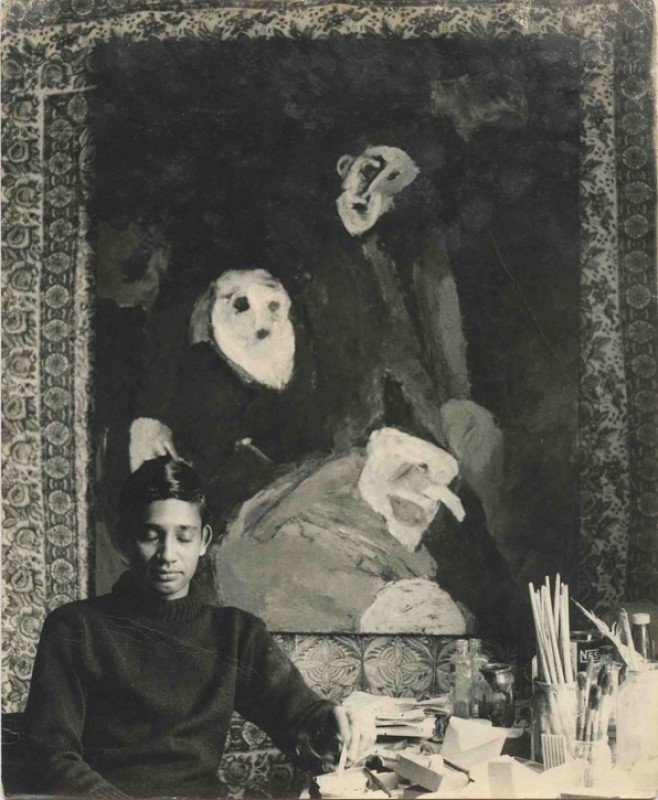

In the years before the First World War, the Slade School of Art in London found they had attracted a golden generation of students – it was what the school's professor of fine art, Henry Tonks, called their last 'crisis of brilliance'.

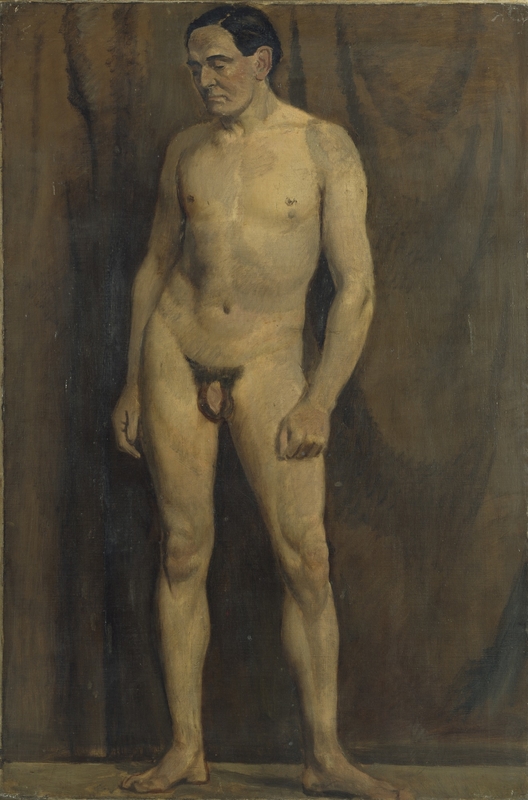

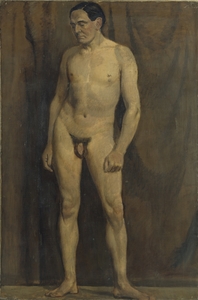

Along with Christopher Nevinson, David Bomberg, Stanley Spencer and Mark Gertler, Thomas Saunders Nash was already recognised as a highly gifted and original painter by the time he was awarded the school's First Prize in Drawing and Painting from Life in 1912, the year he graduated.

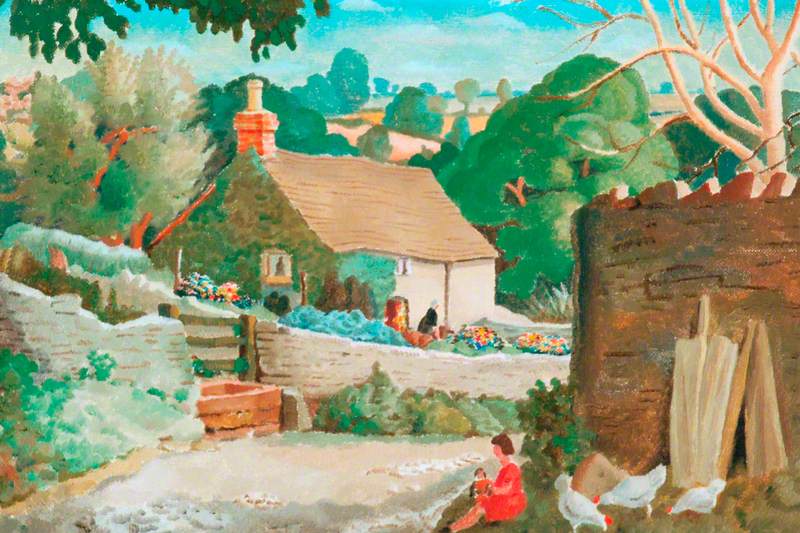

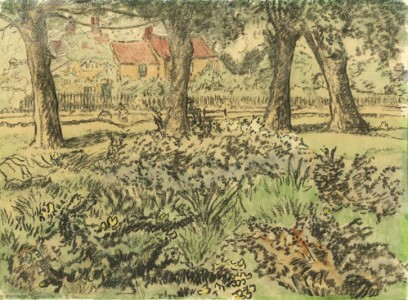

The middle son of Henry and Lydia, Thomas was born in July 1891 at Walton-on-the-Hill, Surrey, into a family whose main income came from his father's job as a railway signalman. The family's cottage overlooked the parish church of St Peter. It was here, aged seven, Nash claimed to have had his first visitation when studying a copy of Murillo's painting The Madonna and Child, which still hangs in the church's Lady Chapel.

It was soon after this revelation Thomas discovered he had a talent for drawing when he was involved in a serious skating accident and spent several weeks in hospital. The accident left one of his feet permanently disabled.

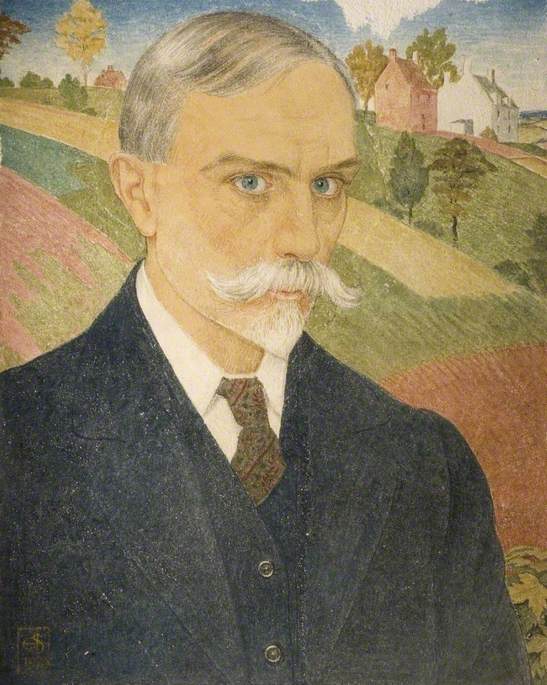

His art education began at the Epsom Technical Institute and School of Art when he was 14 years of age. Three years later he was interviewed by Fred Brown and the formidable Henry Tonks, respectively the professor and head of drawing at the Slade. His portfolio must have impressed because the usual entrance examination was waived, and Nash was accepted, supported by the artist and philanthropist Violet Eustace, who paid his fees.

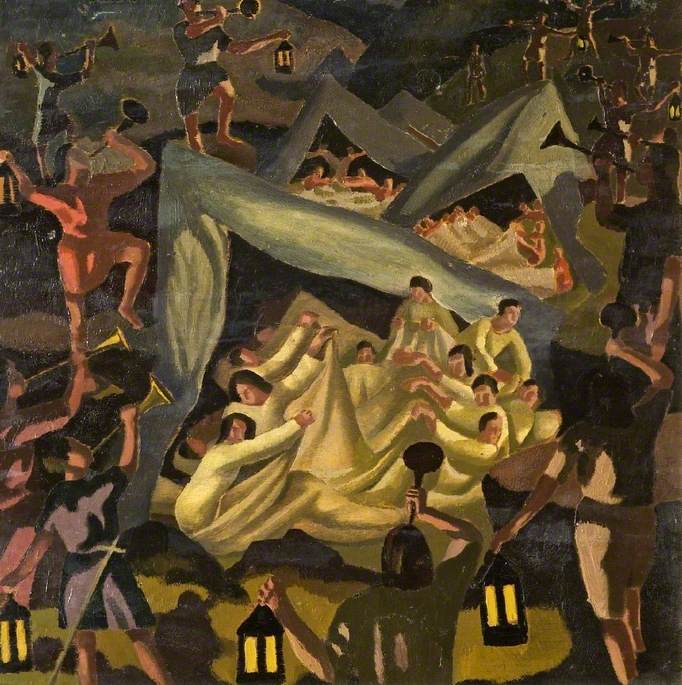

Nash's earliest work was poetic, lyrical and heavily influenced by reading the bible and experiencing almost daily 'visions and experiencing dreams', which he sought to paint as accurately as possible. During his first term, he joined the Slade Sketch Club which was structured around a series of set composition subjects and monthly prizes; he produced a total of twelve drawings, all inspired by biblical or literary themes.

His own, early taste in art points to Pre-Raphaelitism, which at this time remained popular with some Slade students – it was also seen as a continuing tradition in English painting. Other influences were the French Symbolist artists, notably Puvis de Chavannes, who was very popular in England at the time, and early Renaissance Italian painting, especially Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Fra Angelico and Giotto, whose large bulky figures are not dissimilar to Nash's work of the period.

Soon after leaving the Slade, Nash trained as a teacher and afterwards settled into a rhythm in which teaching and the practice of painting complemented each other; a regular wage was necessary after his marriage to Muriel Maud Emery in 1914. The First World War, which created shortages in so many areas, created them also in the teaching profession: many of the schoolmasters available at the time were either elderly, having been brought out of retirement, or young, inexperienced and awaiting conscription.

In his private journals, Nash stated that he and Muriel often struggled with the cost of married life. 'I do worry where the next shilling is coming from, and I hate the obsession we have with money.'

He had, for some reason, not exhibited at any recognised gallery since leaving art school but that changed in 1920, when he entered two biblical-themed pictures for the New English Art Club, as he did the following year as plain Tom Nash, alongside David Jones and Stanley Spencer.

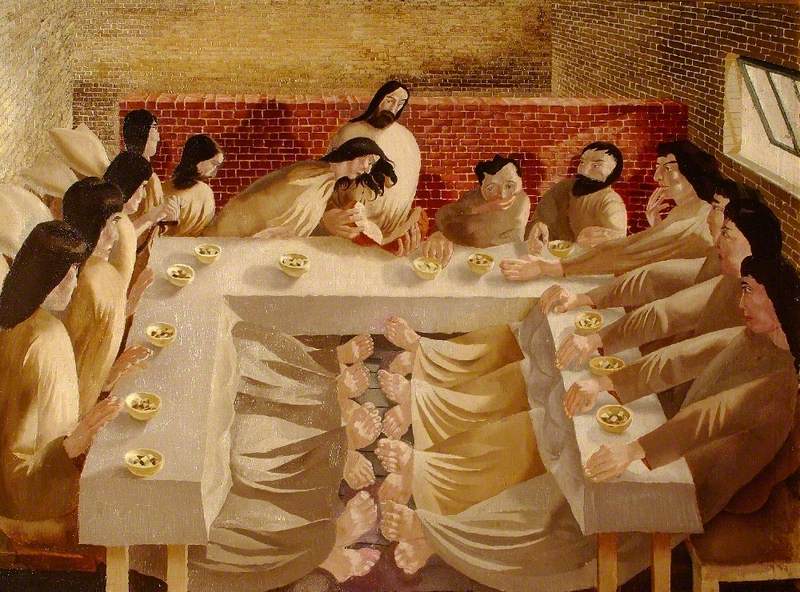

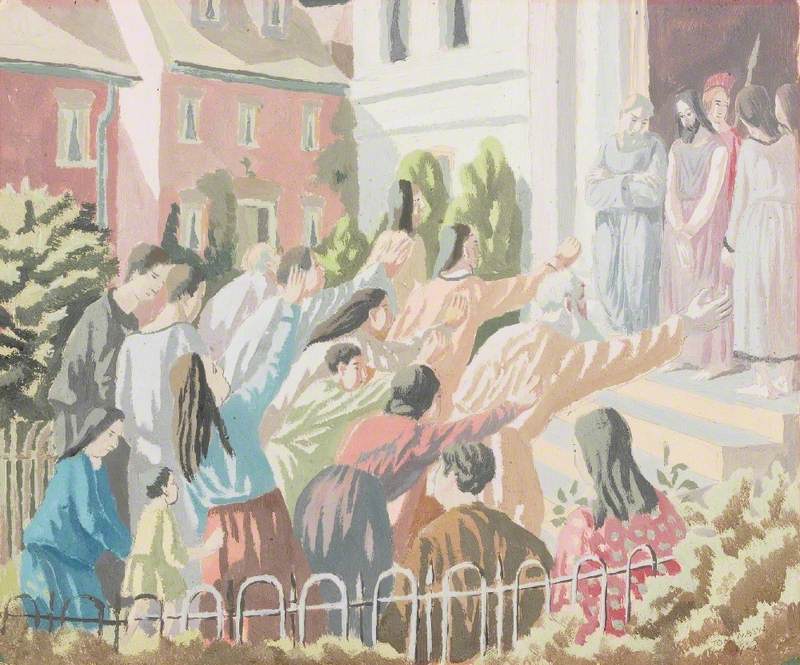

The 1921 show was not a great success for painters who were inspired by the Italian primitives. The art critic for Truth, the newspaper founded by the politician Henry Labouchère, singled out Stanley Spencer's The Last Supper as 'quite repulsive in colour,' while writing that Tom Nash's painting of Women Looking for Christ 'looks like a rehearsal for a Garden City pageant.' (The newspaper gave no definitive description of what Women Looking for Christ looked like – it could be the same painting or a different one to Christ before the People, now at the Laing Art Gallery; Nash did occasionally retitle works after poor criticism.)

From his journals, it is clear this criticism was a blow to his self-confidence and he struggled with carrying on, writing: 'In vain do individuals hope for immortality, or at least from oblivion.'

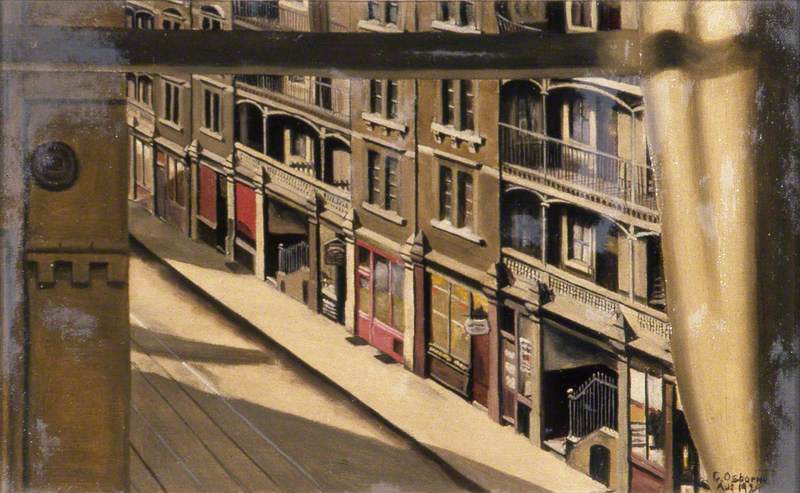

That autumn he entered a small painting for a mixed show at the Goupil Gallery and found himself praised for originality in a press notice published in the Evening Standard. It was hard-won acclaim, as his diary reveals the hardships of finding time away from teaching to paint was extremely difficult, as he started the school day at 8am and ended it twelve hours later.

He saw artists as a race apart and suggested that they contended with agonies unknown to other solitary creators such as writers. Even so, he persisted and reacquainted a friendship with Stanley Spencer's brother Gilbert Spencer, who had been in the same year as Nash at the Slade. He was looking for a house to rent, so Thomas invited Gilbert to lodge with them, which he did at their cottage at Caversham in Reading.

It was partly through Gilbert and Stanley Spencer's interventions that Arthur Knyvett-Lee and Anthony Maxtone-Graham, founders of the Redfern Gallery, offered Thomas gallery space in 1927. The show caught the attention of collectors, including Thomas Balston and the polymath Edward Marsh.

The Westminster Gazette noted the majority of the paintings had already been bought by the time the show opened. The newspaper singled out Nash who its critic described as 'an intensely religious school teacher', and noted that Stanley Spencer's painting Resurrection was 'painted in a rather similar genre' as Nash's Angels Appearing Before the Shepherds.

'The question now seems to be: did Spencer copy Nash, or Nash, Spencer? Both of them seem pre-occupied with religious subjects.'

Quite what Spencer made of this review isn't recorded but he chastised Nash in later life saying that, at the Slade, 'Nash walked about with a Bible in one hand and my ideas in the other.'

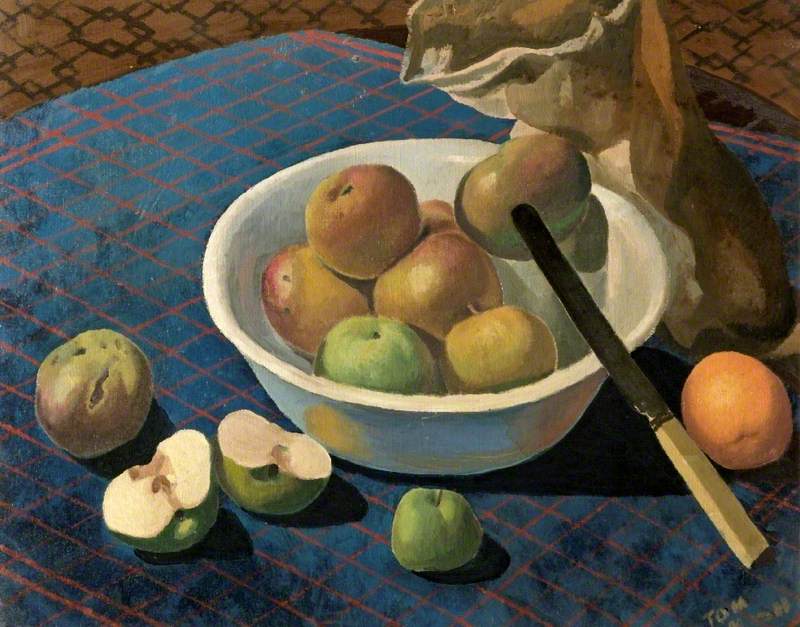

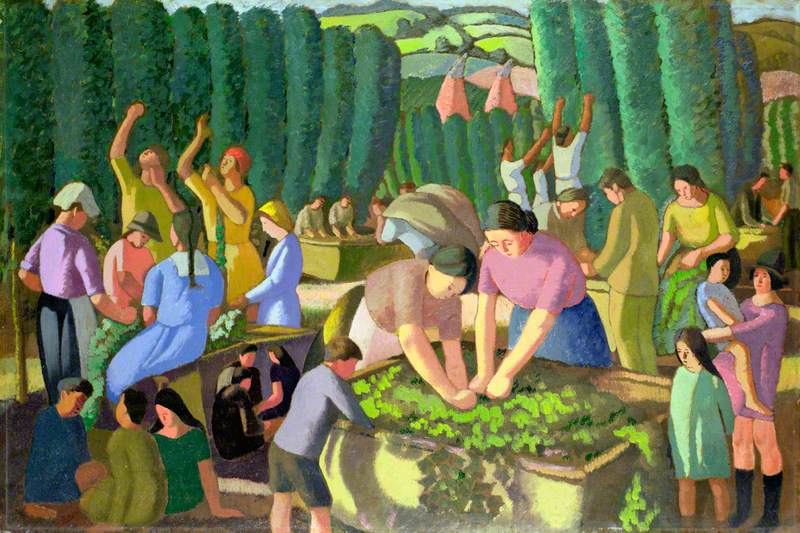

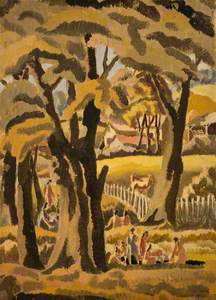

For all the exhibition's good news – The Ashmolean in Oxford bought In the Orchard (The Applepickers) – it was a dark year domestically. In theory, Gilbert Spencer's intimate relationship with Mabel was a closely guarded secret until Nash discovered the two in bed together; Gilbert agreed to sign as co-respondent (he was a model of decisiveness when he had to be) with Mabel and Thomas divorcing in 1928 just before Nash's pictures were hung at the Redfern Gallery, alongside those of his friend Adrian Allinson and the war artist George Edmund Butler.

In the months leading up to the show, Nash had sold a number of pictures, including one to Thomas Balston for £25. His patron resolved to introduce him to the British art dealer Joseph Duveen, who was considered, even then, one of the most influential art dealers of all time. The year passed in a rush as Nash prepared for an exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, which, when it was over, he called 'a partial failure'.

To add to his always perilous financial problems, his second marriage that October to Emily Gurr meant he needed to find a full-time job; his prevailing conviction that he was born to be an artist was checked by the mundane business of paying bills.

In March 1930, writing from 4 Council Cottages, Tadworth in Surrey, Nash revealed in a letter to Balston that he was unable to complete commissions. Even so, that month a selection of his drawings went on show at the Festival of Contemporary Arts at Bath, alongside work by Henry Moore, Vanessa Bell and William Nicholson.

Later that summer, Nash later sold Crucifixion (completed in 1928) to the Contemporary Art Society for £50, but despite all these efforts – which included sending work to Duveen's British Artists' Exhibition, a touring scheme to introduce new artists to the public – his sales amounted to very few.

Thomas proved less tractable an artist than his backers had hoped, particularly Duveen, who was now buying his work, and in 1930, Nash secured a post as arts master at Ackworth School, a Quaker boarding school near Pontefract, West Yorkshire. The appointment was helped by the historian and educationalist Sir Michael Sadler, who had been born in Yorkshire and had many friends in the county.

Before his departure to Yorkshire, Sadler had arranged for Nash's pictures to be shown at the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, where they were received with a standing ovation at the private view.

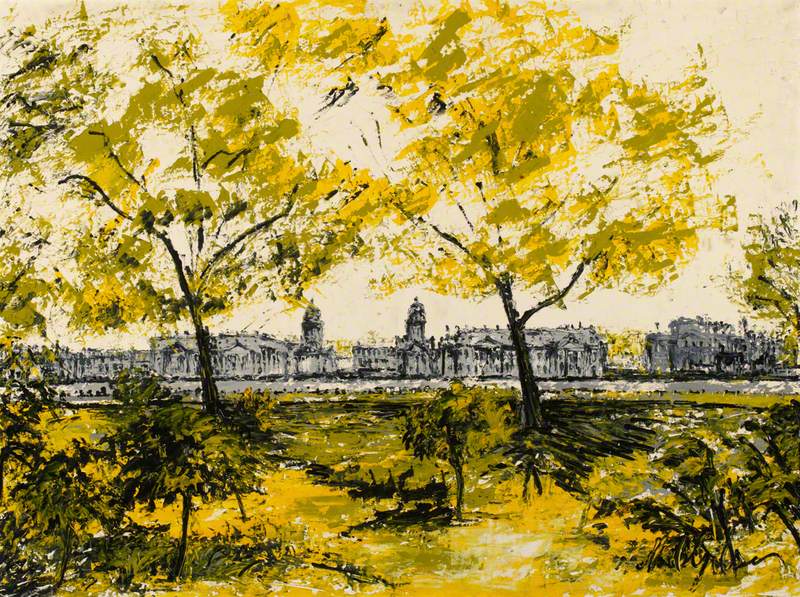

Thomas continued sending work to London – notably to the Royal Academy in 1934 – and made the most of his connections with the Ferens by submitting work to their shows on a regular basis.

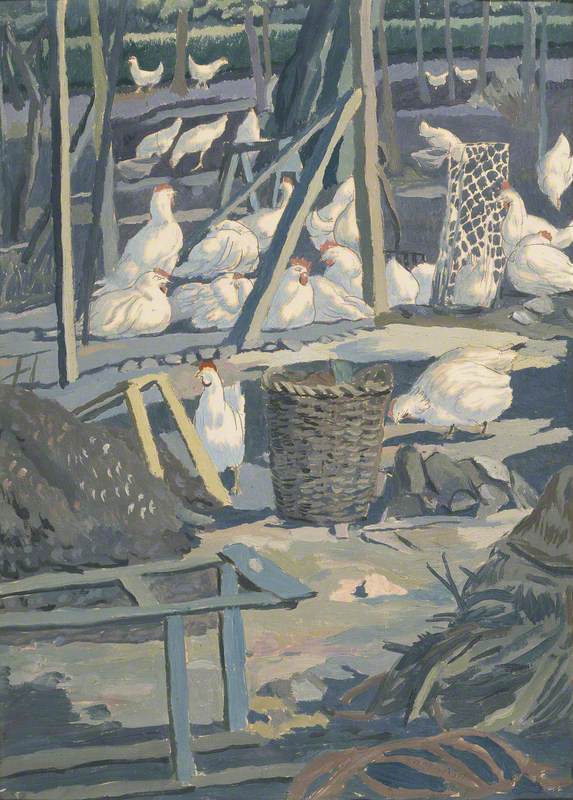

The subsequent arrival of a son, David, in 1935 and caring for two daughters that Emily and Thomas had adopted, meant his domestic budget clashed with buying materials to continue to paint. He submitted work to the New English Art Club's autumn exhibition in 1936, where his painting of beehives attracted the attention of T. W. Earp, the art critic for the Daily Telegraph, who praised the picture as 'very satisfying'.

Nash's valedictory submission to the Royal Academy's annual exhibition was in 1941. When Nash died in January 1968 at Poole in Dorset, at a little over 76 years of age, he had given his all to his family and teaching art. It wasn't that he was out of contact with the commercial art world, he just chose not to participate in it.

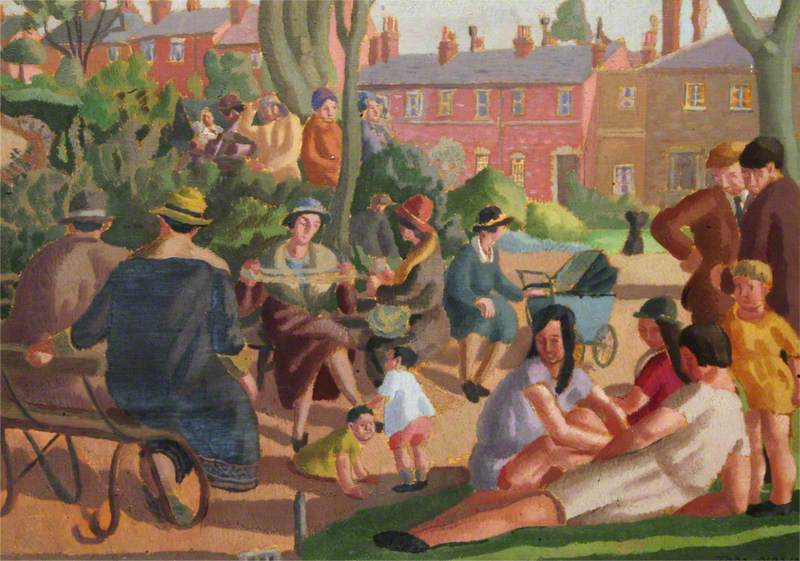

In the catalogue for his retrospective at Reading Art Gallery in 1979 the art historian Charles Tracy wrote: 'Nash's artistic manifestations of subjects from both the New and Old Testaments are self-conscious reconstructions of the events in a generalised contemporary English setting... Whether or not Nash was a religious man, his treatment of sacred subjects is suffused with a powerful religious instinct.'

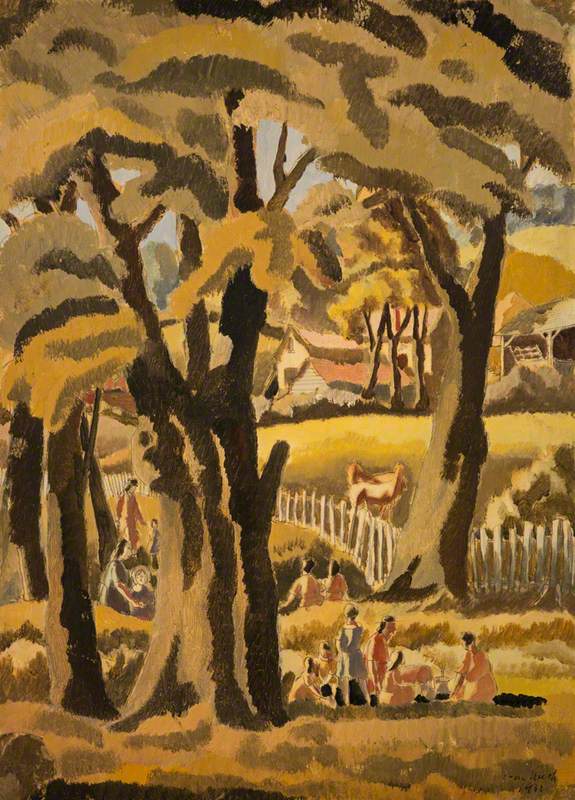

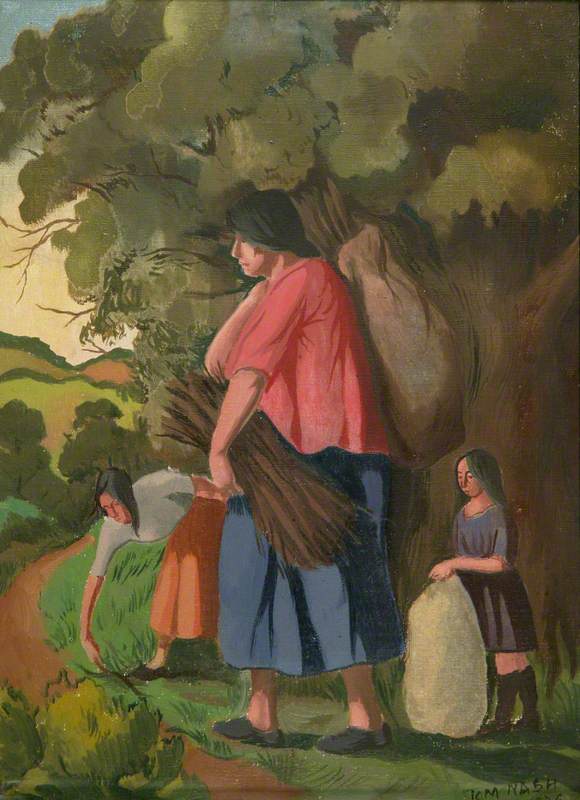

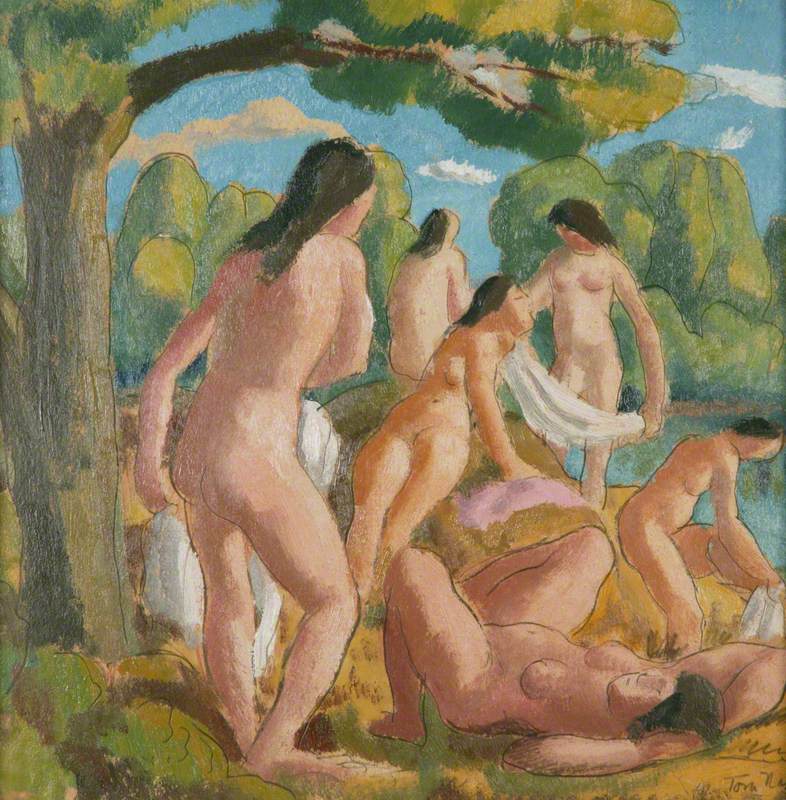

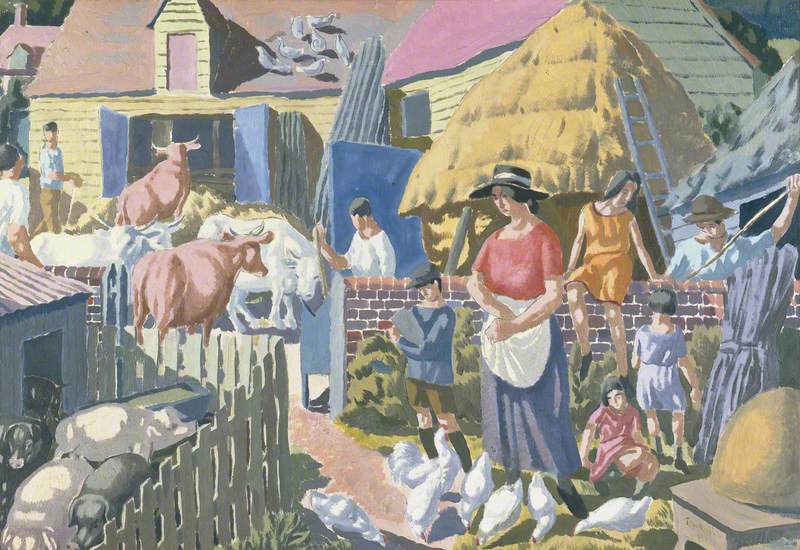

It may be argued that Nash's work of a religious theme was influenced by Stanley Spencer but we should focus instead on those aspects of his art which made him a familiar presence in the 1920s and 1930s – his ability to create a melding of the everyday and the mystical into a homespun figurative style that, at its best, is transcendent.

Richard Morris, art historian

Prints of Thomas Saunders Nash's paintings can be purchased, framed or unframed, from the Art UK Shop