The women's bathroom – a place of intimacy, mystery and spectacle. Few of us can deny its seductive power. From its role in our daily private ablutions to its allure as a hothouse of gossip, comfort and conflict, the women's bathroom is multifaceted. It can serve as confessional booth, therapist's couch and safe haven all in one.

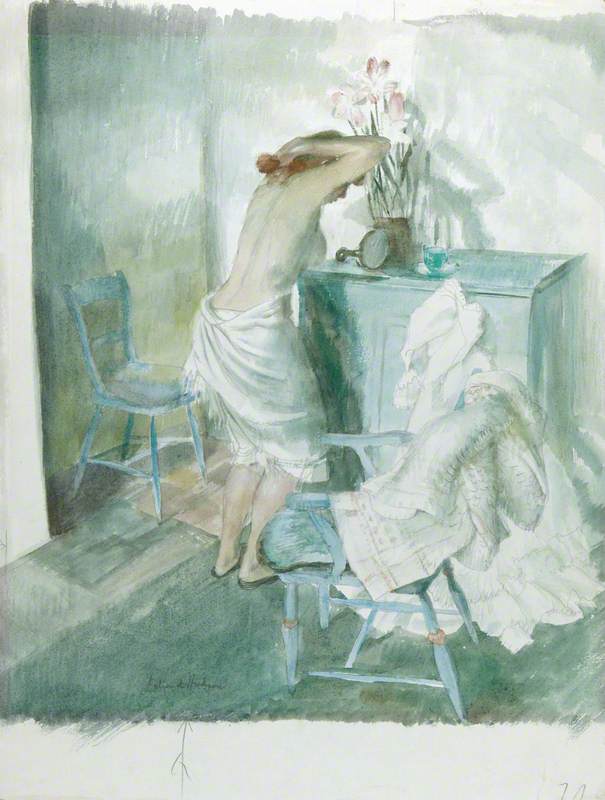

The origins of this hallowed space may be found in the morning toilette, depicted throughout art history in 'Ladies at their Toilet' or 'La toilette' paintings – a type of painting in which a woman or women are seen in some stage of intimate preparation or private moment, whether styling hair, bathing, applying make-up or getting dressed.

A Lady Dressing Her Hair

c.1657–1658

Gerard ter Borch the younger (1617–1681)

Toilette paintings are typically associated with early modern French art – particularly Rococo paintings – although scenes of women getting ready were a popular feature of Dutch genre painting in the mid-seventeenth century. The theme first emerged in the Renaissance, via depictions of mythological figures such as Venus at her 'toilet', or the goddess Diana.

Not to be confused with the modern understanding of the 'toilet', 'toilette' derives from the French word for a cloth – or toile – that covered a dressing table. As such, the toilette (and hence paintings of the toilette), tends to refer to anything that might form part of one's washing or dressing routine.

It was in the seventeenth century that the toilette became an integral part of the aristocratic daily ritual, as well as a wider social occasion. During the reign of the famously ostentatious Louis XIV, from 1643 to 1715, what modern audiences might see as an ordinary, habitual act became an elaborate ceremony within the Palace of Versailles. The monarch's ritual of dressing in public was known as the levée (from the French verb lever, meaning 'to get up' or 'to rise'), and under Louis XIV, it became a fully fledged ceremony, attended by his entire court – around 100 people. A smaller group enjoyed the privilege of watching the king wash and shave.

A Gentleman's Toilet (La petite toilette)

Jean-Michel Moreau le jeune (1741–1814) (after)

For high-ranking, influential female figures such as Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764), the official mistress of Louis XV (1710–1774) and an important political figure in her own right, the toilette was where she regularly conducted business and negotiated with ministers, courtiers and intellectuals – often while still in dressing robes.

Madame de Pompadour at her Tambour Frame

1763-4

François Hubert Drouais (1727–1775)

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this act of conducting business in intimate chambers and in semi-undress infiltrated elite society across Europe. It is seen, for instance, in William Hogarth's (1697–1764) A Rake's Progress: 2 – The Rake's Levee, in which the now fashionable Tom Rakewell entertains a busy crowd at home. Notably, he is shown in slippers and without a wig, instead wearing a house cap that was typically worn in the bedchamber, or in this case, for entertaining informal guests.

Similarly, plate 4 of Hogarth's Marriage A-la-Mode: The Toilette (c.1743) depicts an Englishwoman of obvious means entertaining visitors while completing her toilette. This is a clear nod to the aristocratic French penchant for having visitors while getting dressed.

Marriage A-la-Mode: 4, The Toilette

about 1743

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Elsewhere, Nicolas Lancret's (1690–1743) painting The Four Times of Day: Morning from 1739 shows a young woman attending to a priest over breakfast, while only half-dressed – her breast is exposed as she turns away from her dressing table to pour tea.

Such works differ from the more private depictions of the toilette, seen in The Modiste (c.1746) by François Boucher (1703–1770), in which a woman considers various pieces of fabric while seated at her dressing table. The slight mess of the room is indicative of the intimacy of the space we are looking at.

As with much of the ceremony and tradition of the ancien régime (the 'old order'), the French Revolution in 1789 and the growth of Enlightenment ideas brought a new perspective to the toilette. In the early eighteenth century, it had been seen as an activity and space that was occupied and enjoyed by both men and women. By the mid-1750s, however, the toilette had been designated an exclusively 'feminine' practice.

Portrait of a Lady at Her Toilet Table, Dressed in a Peignoir

c.1740–c.1760

French School

As Enlightenment ideals reshaped society, the once-celebrated rituals of the toilette (particularly the application of make-up) began to be seen as excessive and deceitful. During the reign of Louis XIV, the application of cosmetics (by both sexes) was a marker of aristocracy, but by the French Revolution it had become entirely feminised and associated with the treacherous, performative former elite – including figures such as Madame de Pompadour and Marie Antoinette, who was Queen of France from 1774–1793.

Pompadour at Her Toilette

1750, oil on canvas by François Boucher (1703–1770)

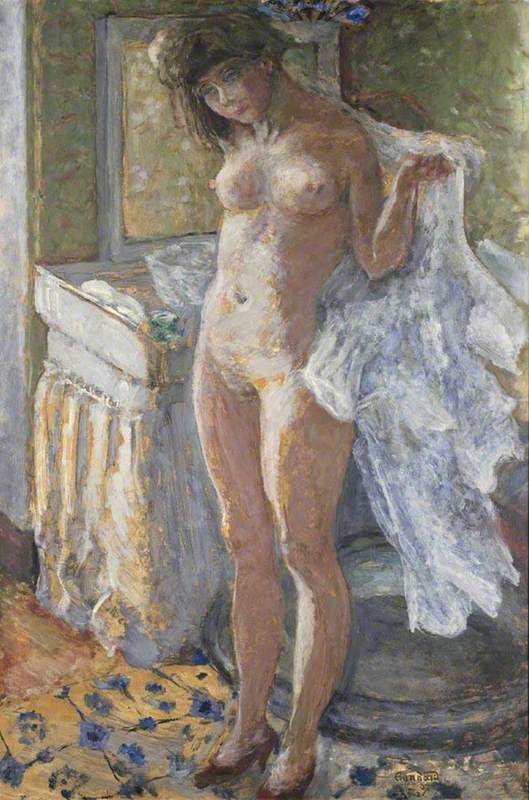

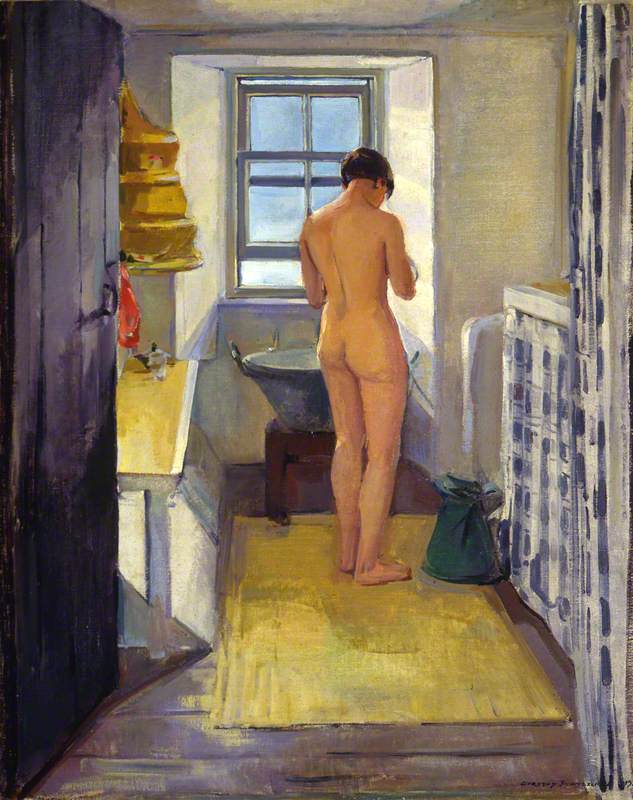

Throughout art history, depictions of the toilette have frequently been voyeuristic and erotic in nature, deliberately inviting a male gaze. This is largely due to the fact that these works were painted almost entirely by men, imagining a space they themselves were unlikely to frequent. Such works made the space and rituals of the toilette public, as well as open to societal scrutiny and harsh judgement, something which grew in the wake of the French Revolution and dissolution of the monarchy.

An Elegant Woman Dresses

1796, oil on canvas by Michael Garnier (1753–1819)

Consequently, many toilette paintings show women in a compromising position or state of nudity. Such paintings transformed the toilette into a seductive, even comical space fantasised about and objectified by men, and where the female subject became an object of titillation. While men are rarely depicted, it is clear such paintings reflect male notions of what women could and should be doing in their most intimate moments – consider, for example, Boucher's provocative La Toilette intime (Une Femme qui pisse).

In The Bath (Le plaisir de l'été), we see a bathing woman ogled by a Peeping Tom at the window, while in Jean-Antoine Watteau's (1684–1721) earlier work, A Lady at her Toilet, the subject stops mid-dress to smile coyly out at the viewer, openly displaying her full nakedness.

More moralistic overtones can be found in a sub-genre of toilette paintings called beau désordre, which emerged in French Rococo art. Set within an interior, these paintings attempted to form a symbolic link between the dishevelment of a room and the promiscuity of the woman. This is clear in The Broken Mirror (c.1762–1763) by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805).

Depicted at her toilette (a string of pearls and powder puff are seen on her dressing table), this woman is shown in a clear state of distress with undone hair, a cluttered room and a suggestively unlaced gown. She looks down sombrely at a broken mirror and her barking dog, both symbolic of the loss of virtue.

The genre of toilette painting continued to fascinate artists into the modern period and remained a constantly evolving subject. In the nineteenth century, thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the growth of an urban class, we see a shift away from the toilette as a predominantly aristocratic space.

A Woman Tying up her Hair Seen from Behind

1891

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

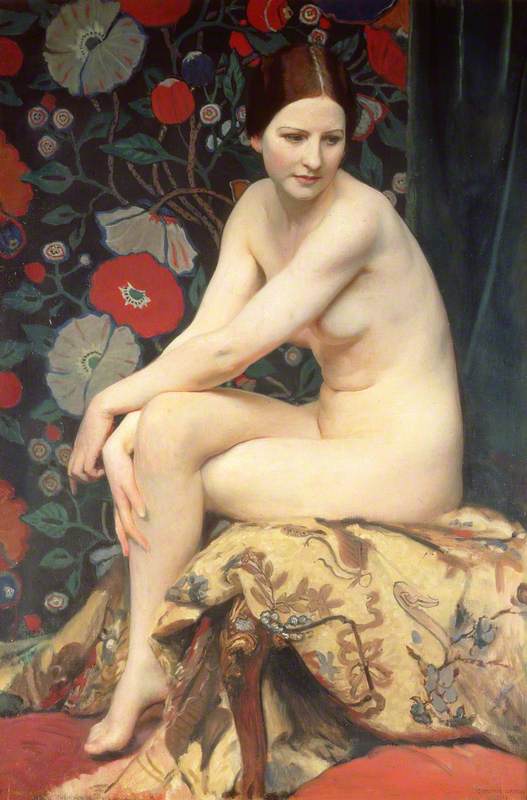

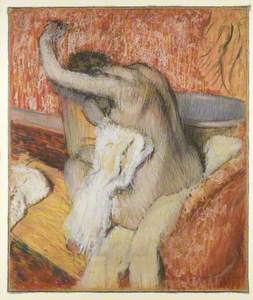

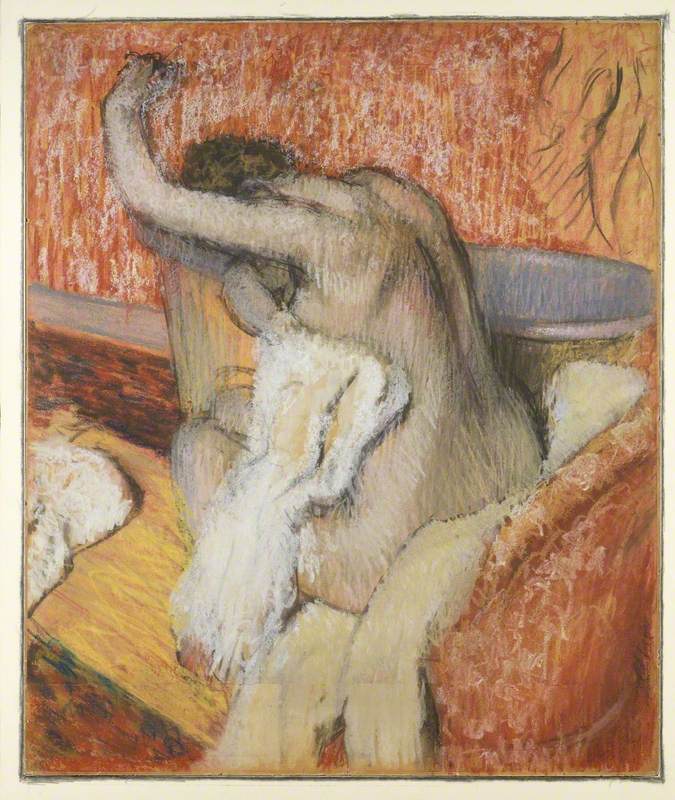

French artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), and Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947) focused more on the toilette's intimacy, and the private glimpses it gave into everyday experiences of ordinary, working women – albeit from a male perspective. The theme often provided an excuse for male artists to paint a nude figure in various states of undress.

After the Bath – Woman Drying Herself

c.1895

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

Significantly, many modern women artists such as Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), Eva Gonzalès (1849–1883), and Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) turned their attention to toilette paintings, producing works that reveal the subtle power of the female gaze. The feminine domestic interior was a space that women artists could claim at a time when depicting other scenes from daily life – such as theatres or nightclubs – was easier for their Impressionist male counterparts.

Woman at Her Toilette

1875–1880, oil on canvas by Berthe Morisot (1841–1895)

Depictions of women at their mirror, such as Gonzalès' The Full-Length Mirror (1869–1870), were popular among Impressionist artists (in art history, the mirror is a symbol of both vanity and interiority). These works, alongside later examples like Black and Yellow by Scottish artist Dorothy Johnstone (1892–1980), may be seen as a wider part of the toilette tradition in their focus on the daily ritual of getting ready for the day.

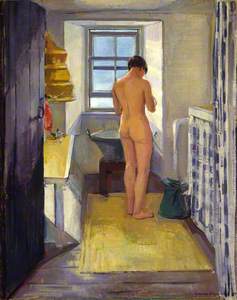

A more recent work from 2017 by Rebecca Harper (b.1989) offers a startling interpretation of the toilette theme. Here, a woman, seemingly post-shower with a towel wrapped around her head, is shown standing with her back to a man in a shower, his gaze meeting ours. A decidedly everyday scene, the work is unusual in turning traditional depictions of women getting ready on their head, with the female gaze of the artist focused on the male nude figure.

This brief history of 'ladies at their toilette' paintings brings us back to the contemporary idea of the women's bathroom as a space of ritual, reflection and social interaction. Perhaps more significantly, these historical depictions of the toilette resonate with questions today around privacy and public scrutiny – when digital media has collapsed the boundaries between private and public, and bathrooms are often cited in wider debates around gender identity. Just as toilette paintings are filled with meaning, the women's bathroom emerges as a site that is anything but neutral.

Grace England, writer and art historian

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Yves Carlier, 'Details of the Toilet Service of the Duchesse de Cadava' in Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts, vol. 78, no. 1/2, 2004

Elise Goodman-Soellner, 'Boucher's "Madame de Pompadour at Her Toilette"' in Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 17, no. 1, 1987

Melissa Hyde, 'The "Makeup" of the Marquise: Boucher's Portrait of Pompadour at Her Toilette' in The Art Bulletin 82, no. 3, 2000

Melissa Hyde, 'Rococo Redux: From the Style Moderne of the Eighteenth Century to Art Nouveau' in Sarah D. Coffin (ed.), Rococo: The Continuing Curve, 1730–2008, Cooper Hewitt Museum, New York

Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, 'Pompadour's Touch: Difference in Representation' in Representations 73, no. 1, 2001

Mary Sheriff, Fragonard: Art and Eroticism, University of Chicago Press, 1990