Broadly speaking, genre painting depicts scenes of everyday life. Such scenes proliferated in the Netherlands during the seventeenth century, with subject matter including taverns, markets and domestic interiors. The region's economic growth during this period played a role in the rise of genre painting – a fast developing middle-class had money to spend on art to decorate their homes. Scenes mirroring their own contemporary lives had huge appeal.

The term itself is slightly confusing. In art history, 'genre' means 'type' or 'category' and is used to describe broader subjects of painting such as history painting or still life. 'Genre painting', or painting scenes from everyday life, is a different category within this umbrella term.

A hierarchy of genres was established in the seventeenth century by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture which identified five categories of varying importance. 'History painting' was seen as the most important genre, followed by 'portraiture', 'genre painting', 'landscape' and 'still life'. These latter two were ranked lowest because they didn't include people, unlike history painting, which was placed highest because it also depicted grand events and was seen to have intellectual weight.

Genre painting sits in the middle of these five categories, in part because it includes depictions of people – albeit ordinary people, both rich and poor. Nevertheless, genre works would have been dismissed as vulgar and trite in comparison to battle scenes or aristocratic portraits. It's worth noting, though, that the boundaries between these hierarchies frequently blur – genre painting, for example, often combines elements of history painting, portraiture and still life.

If genre painting's beginnings can be traced to northern Europe, then its roots are to be found in the sixteenth-century peasant scenes of Flemish painter Pieter Bruegel the elder. His realistic, honest depictions of everyday activities such as country fairs or weddings reveal his attention to detail; this is an attempt to capture life in all its variousness.

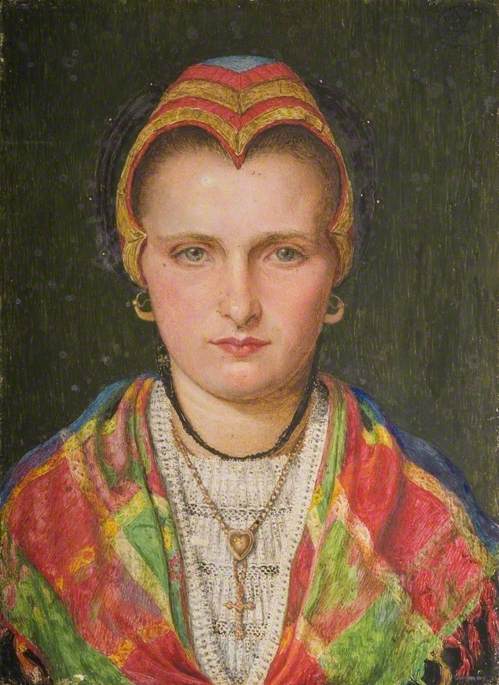

Image credit: Perth & Kinross Council

Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569) (school of)

Perth & Kinross CouncilIn the Netherlands, Hendrick Avercamp's winter landscapes recall Bruegel, while early proponents of the genre such as Frans Hals, Hendrick ter Brugghen and Willem Buytewech reveal their mastery of merrymaking scenes.

The influence of Caravaggio is clear in Ter Brugghen's luminous depictions of musicians – a subject Hals was drawn to in the 1620s. His Merry Lute Player (c.1624–1628) shows his skill at capturing something of his sitters' characters, and makes clear why genre painting is seen to overlap with portraiture.

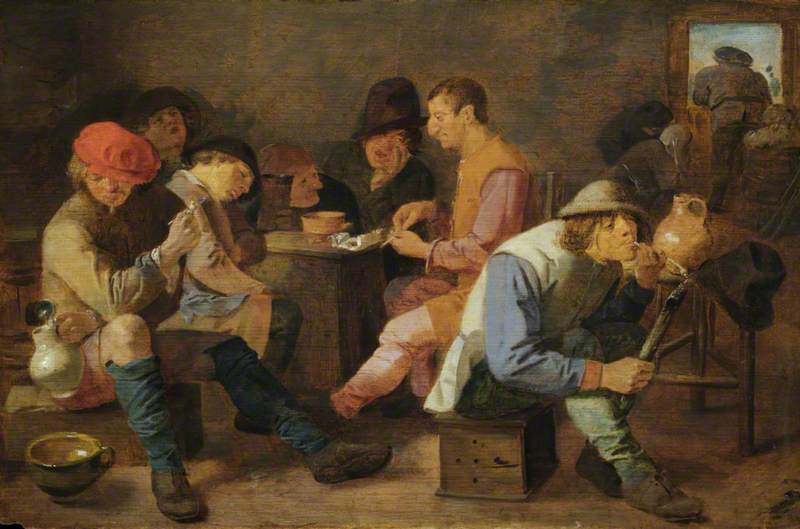

Hals' pupils Adriaen Brouwer and Adriaen van Ostade were especially adept at low-life tavern scenes.

Image credit: National Trust Images

The Interior of an Inn with Peasants Playing Cards 1674

Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685)

National Trust, AscottThe obvious humour in Brouwer's work lies in his capacity to capture human expression – he particularly revelled in showing people smoking, which was associated with disreputable behaviour in the Netherlands at this time.

Having studied under Rembrandt, Nicolaes Maes initially focused on history painting but his inventiveness, as well as the lessons he learned about light and dark, are clear in his intimate genre scenes. His series of eavesdroppers set up a unique relationship with the viewer thanks to the direct gaze of his figures, and the different points of action within these works reveal Maes' ability to create the illusion of space.

Women undertaking ordinary tasks often form the centre of Maes' genre works. He was especially drawn to the milkmaid, a figure made famous a few years later by Johannes Vermeer – today perhaps the most celebrated of Dutch Golden Age genre painters.

Image credit: Rijksmuseum, CC0

The Milkmaid

c.1660, oil on canvas by Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675)

The Milkmaid (c.1660) evinces the quiet absorption that characterises Vermeer's works, which often focus on one subject – usually a woman – engaged in a task. He had a special ability to make the ordinary extraordinary, aided by his unparalleled skill at capturing light.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

A Young Woman standing at a Virginal about 1670-2

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675)

The National Gallery, LondonWhile The Milkmaid elevates a humble life, Vermeer is primarily known for genre scenes depicting the pastimes of the middle class, as well as those reflecting the increased wealth of merchant families who required a high-end art to match their superior social status. The genre scenes of Gerard ter Borch the younger similarly drew attention to the daily lives of the well-heeled – letter reading and writing, music-making, courtship – which were increasingly popular in the third quarter of the seventeenth century.

Maes' experiments with intimate, interior space had a huge influence on Vermeer and another Delft master Pieter de Hooch. Women and children are at the heart of De Hooch's predominantly domestic early genre works. Like Maes, De Hooch's work is characterised by views into other rooms or spaces via open doors and windows.

Creating complex spatial arrangements is a common feature of Dutch genre painting. Consider A View through a House (1662) by Samuel van Hoogstraten, who uses the trompe l'oeil device to create perspective and trick the viewer into reading depth into the work.

Jan Steen signals how the theme of merrymaking remained a popular subject, with this work from around 1674 also referencing the earlier Flemish tradition of the tavern scene. The convivial painting seems to contain all human life – from mothers and children to young dancers and old women – but like many Dutch genre scenes it has moralising overtones.

The phrase 'a Jan Steen Household' is a common saying in Dutch which conjures the warm chaos of his homes.

It's worth saying that the impact of Dutch low-life painting was felt in Spain during the seventeenth century, when artists produced bodegónes (from bodegón, meaning tavern). Bodegónes also refers to still life paintings, but in the early seventeenth century there was a separate tradition of works depicting people with food and drink, often set in taverns or kitchens. A prime example is Diego Velázquez's An Old Woman Cooking Eggs (1618).

Following three wars with England, the last one of which coincided with a battle with France in 1672, the production of paintings in the Netherlands waned and with economic decline came a collapsed art market. By the mid-1670s, the Dutch Golden Age, and with it the appetite for genre painting, was over.

In the eighteenth century, however, genre painting became popular in France – earlier artists such as Louis Le Nain had paved the way with realistic portrayals of peasants – and the influence of the Dutch masters can clearly be seen in the work of Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin. Yet this was at a time, up until the 1780s, when the hierarchies of genre were still adhered to; in France, history painting was king. Despite this, it attracted collectors and a wide public.

Chardin, who primarily produced genre scenes from the 1730s to the 1750s, is well-known for his depictions of children, maids, and figures engaged in everyday activities.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

The Young Schoolmistress probably 1735-6

Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699–1779)

The National Gallery, LondonA master of the interior, he painted the servants' quarters and the private spaces of middle-class families with equal care and attention. The Scullery Maid (1738) is indicative of his ability to glorify the commonplace, the different shades of brown perhaps suggestive of the dreary work the maid is engaged in. The pots and pans on the floor also point to Chardin's skill as a still life painter.

Image credit: The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699–1779)

The Hunterian, University of GlasgowThe romanticised genre scenes of Jean-Antoine Watteau and Jean-Honoré Fragonard contrast greatly with Chardin's realism. Both artists are known for their fête galantes – dreamy scenes featuring fashionable well-heeled young people in lush parkland settings. Watteau often drew on the popular commedia dell'arte, as well as focusing on music-making.

Genre scenes depicting the luxurious, privileged life of the upper classes can be found in the work of François Boucher, who trained as a history painter yet was equally adept at idealised rustic scenes. These often featured fetching women wearing silk in pastoral settings, being approached by, or talking to young men.

The trend for sentimentality continued with the work of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, yet he brought a dose of morality alongside. His modern genre painting can be seen in The Broken Mirror (c.1762–1763), in which the disarray of the woman's room speaks to her loose morals (the dog symbolises carnal desire).

Elsewhere, Interior of a Cottage – an interior scene that clearly draws on earlier Dutch realism – takes a poor family as its starting point, the mother caught between the demands of her child and looking after the elderly woman beside her. Greuze was clearly influenced by his rival Chardin's earlier focus on lower-class daily life.

The moral genre painting of Greuze and others such as Étienne Aubry, whose work Paternal Love was praised when it was exhibited in 1775 for its positive depiction of familial happiness, can be found in the work of Louis-Léopold Boilly in the early nineteenth century.

Yet despite the obvious message of A Young Man Vaccinating a Young Child (c.1807), which extols the virtues of being vaccinated against smallpox, Boilly's art – particularly his early works – looks back towards the more sentimental, lovelorn genre scenes of Watteau.

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

Louis-Léopold Boilly (1761–1845)

Wellcome Collection

Where the French moral genre find parallels is in the social satire of the eighteenth-century British artist William Hogarth. Morality tales such as The Rake's Progress (c.1733–1735), a series comprised of eight works, give a damning account of life in eighteenth-century London by exploring the city's sins and vices via the womaniser Tom Rakewell.

Image credit: Sir John Soane’s Museum

A Rake's Progress: 6 – The Rake at the Gaming House 1734

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Sir John Soane’s MuseumAn artistic figure associated with the English Enlightenment, Joseph Wright of Derby – known as the 'painter of light' – often made works about scientific progress. Many of his most important paintings revolve around ordinary people witnessing an extraordinary scientific event.

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump (1768), which aims to show what happens when a living thing is denied air, is a theatrical example of how the artist examined the everyday in the context of the monumental.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump 1768

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797)

The National Gallery, LondonPerhaps the most popular genre painter at this time was the Scottish painter David Wilkie, who had a big influence on the development of genre painting in the early nineteenth century. The Village Politicians, which Wilkie showed at the Royal Academy in 1806, was a runaway success and he was dubbed 'the Scottish Teniers', revealing how he reignited a taste for Dutch genre painting in Britain.

Image credit: Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)

David Wilkie (1785–1841) (attributed to)

Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)Wilkie's depictions of the poor were, however, considered less vulgar than those of David Teniers the younger (note the urinating man below) and thus more appealing to middle class audiences.

Artists who followed in Wilkie's wake included Edward Bird and the Irish artist William Mulready, who abandoned history painting around 1808 due to the huge demand for genre scenes. The Fight Interrupted (1816), in which a vicar disbands a schoolboy fight, shows how his early rural works drew on Dutch genre painting, not least through their moralising message.

Later, in the 1850s, William Powell Frith documented contemporary scenes on a large scale which brought him great commercial success. The Derby Day (1856–1858) and The Railway Station (1862) reveal his skill at capturing the bustle of a diverse crowd, giving a unique glimpse into Victorian life.

It also shows how genre painting overlapped with history painting – although, in this case, Powell Frith is interested in one brief historical moment in the life of ordinary people.

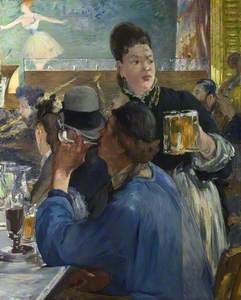

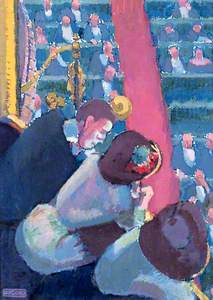

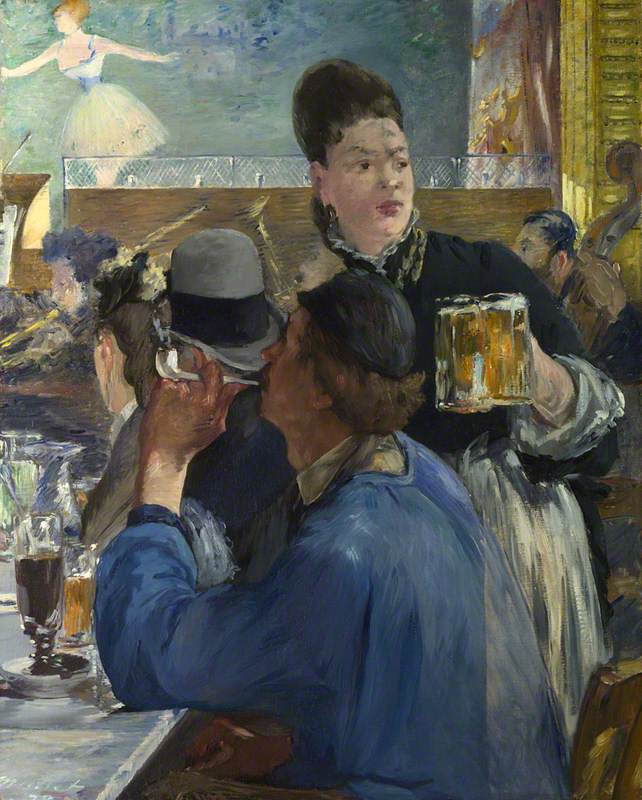

Powell Frith's focus on scenes of everyday life anticipates the Impressionists – Édouard Manet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot – and their depiction of the everyday spaces of modernity such as cafés and theatres. What's more, they tended to work outdoors – en plein air – which gave their works an 'of the moment', fleeting quality.

For Berthe Morisot, her subject was the daily rituals of domestic family life (she was not allowed to go out alone to paint café or bar scenes because she was a woman). A Woman and Child in a Garden (c.1883–1884) is part of a series depicting the artist's daughter, Julie, and a nanny. Situating herself outside the frame speaks to the first-hand quality of Impressionist art, an immediacy aided by the work’s sketchy finish.

According to the poet Paul Valéry, Morisot was 'living her painting and painting her life'.

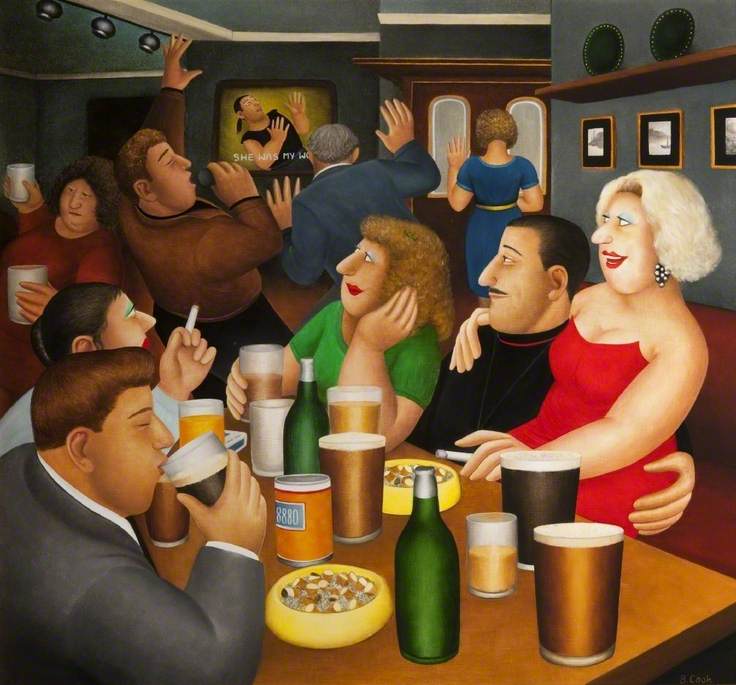

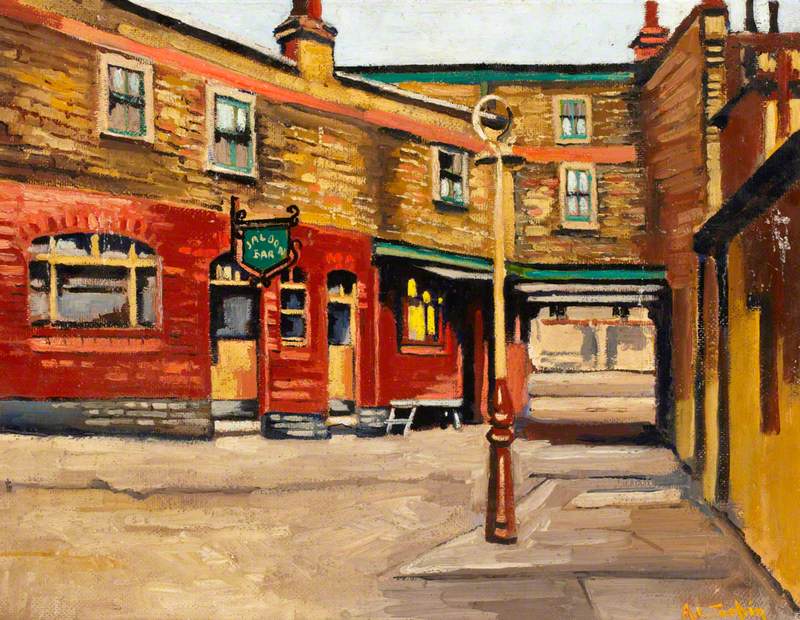

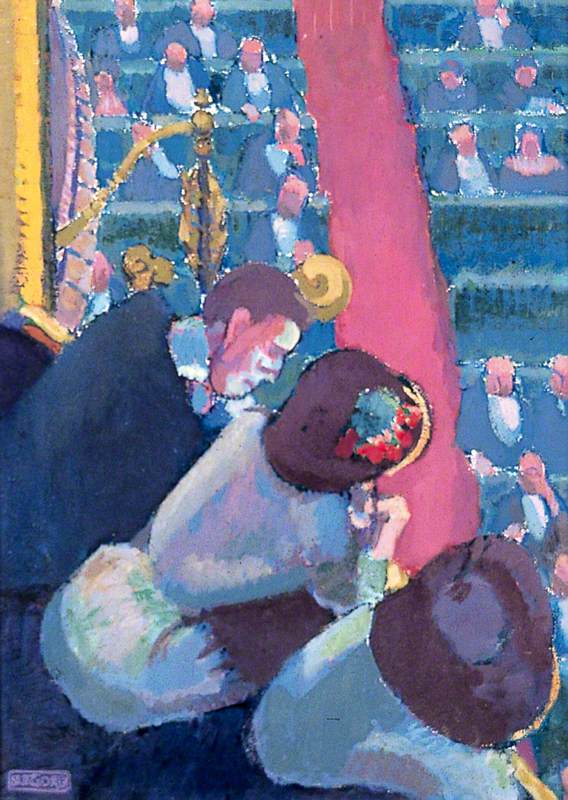

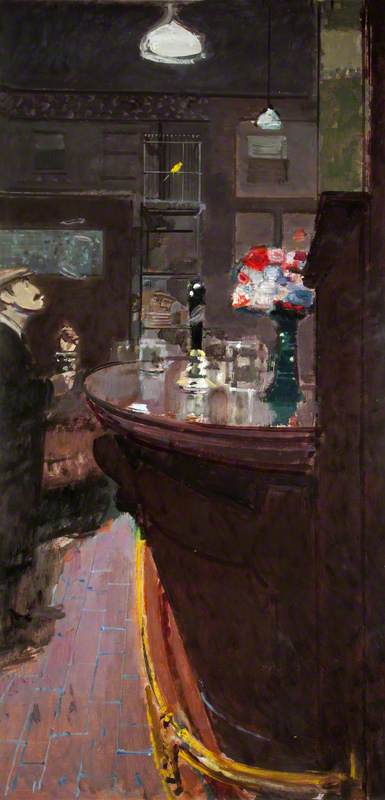

Later British artists such as Walter Sickert and others associated with the Camden Town Group took urban modernity as their focus, which they explored in honest scenes set in London bars, theatres, and music halls – the latter especially attracted Spencer Gore.

Domestic interiors were popular subjects, too, and these were frequently depicted in drab or dreary ways. In Harold Gilman's interiors, made in the early years of the twentieth century, space is often compressed so his works feel both claustrophobic and fleetingly personal. In Sickert's House (1907), the open doors nevertheless play with perspective in a way that recalls the earlier Dutch experiments of Pieter de Hooch.

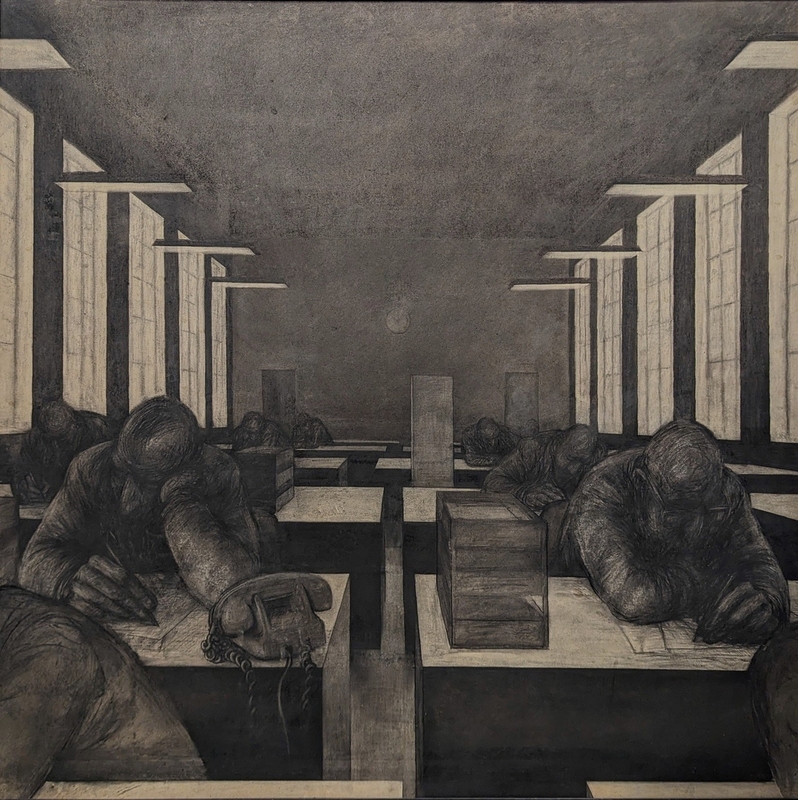

Sickert's American contemporary Edward Hopper (who was inspired by the British artist) produced similar examinations of modern life, although his dimly lit works, such as Automat (1927), are infused with a greater sense of alienation as a result of city living.

Post-war artist Ruskin Spear, who was influenced by the Camden Town Group, made a socially realist art out of affectionately observing pubs in Hammersmith, the area of West London where he was born.

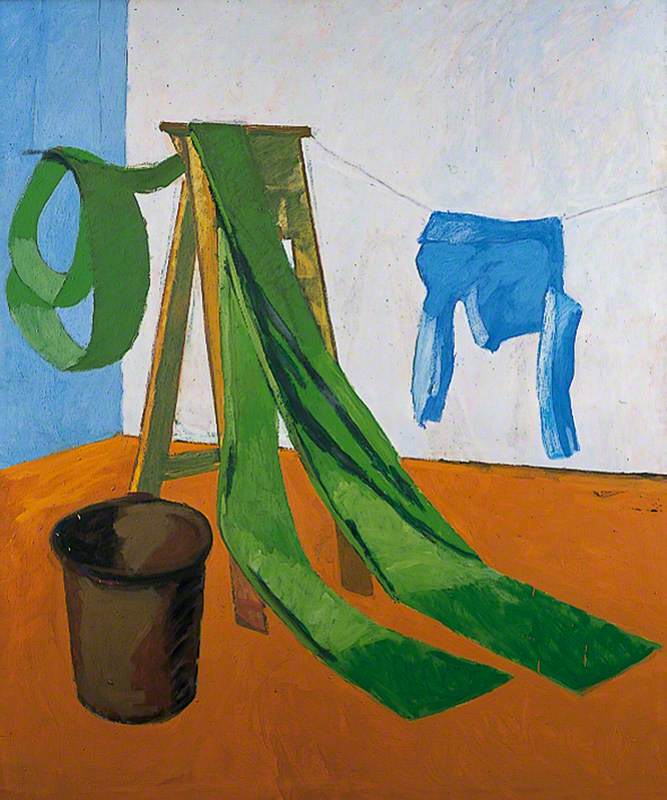

Spear taught many of the Kitchen Sink artists, such as John Bratby and Derrick Greaves, who were active in the 1950s and committed to a kind of hyper-realism in which every ordinary, banal object or person was to be celebrated. As the critic David Sylvester wrote in 1954, their subject was 'Everything but the kitchen sink – the kitchen sink too'.

© the artist's estate / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of Leeds

John Randall Bratby (1928–1992)

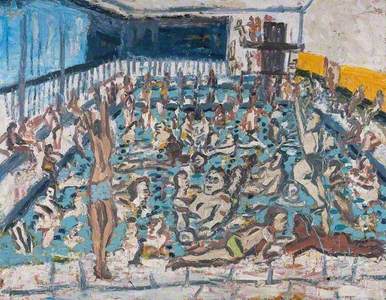

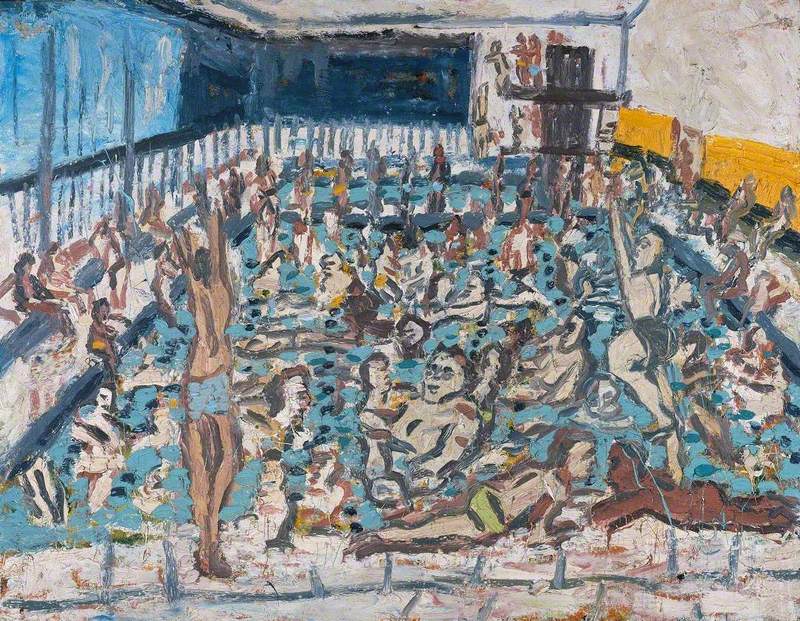

The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery, University of LeedsIn the early 1970s, Leon Kossoff made a series of works based on children playing in crowded swimming pools which capture the frenetic energy at the heart of this everyday activity.

Denzil Forrester's works from the 1980s echo the dynamism of Kossoff's bustling canvases in their vibrant celebration of London's reggae and dub nightclub scene. These are merrymaking scenes for the contemporary age.

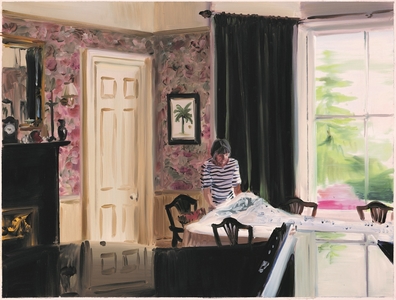

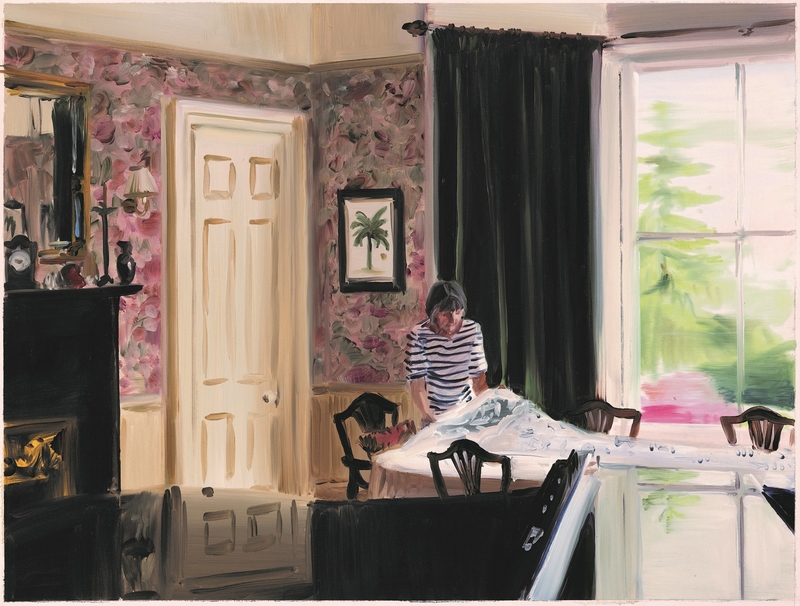

More recently, and in stark contrast, Caroline Walker has turned her attention to quietly intimate, often voyeuristic, depictions of women at work (calling to mind Degas' series of women ironing, begun in the 1870s). Her latest look at women in contemporary society includes a poignant focus on mothers and childbirth – an everyday occurrence that significantly expands on genre painting's capacity to show the stuff of life.

Genre painting's subject matter is varied, running from raucous merrymaking to milkmaids at work and fleeting glimpses into family life. It's a genre that has evolved over the centuries, none more so than when Marcel Duchamp made art out of a urinal, allowing artists to experiment more fully with everyday, found objects such as soup cans (Andy Warhol), mattresses (Sarah Lucas) and bottle tops (El Anatsui).

This is an expanded understanding of genre that can nevertheless be traced back to the village fairs and taverns of seventeenth-century Dutch art.

Imelda Barnard, Art UK Commissioning Editor, pre-nineteenth-century European art and twentieth/twenty-first-century British art

This content was supported by Freelands Foundation as part of The Superpower of Looking

![Beyond the Pleasure Principle [Freud]](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/collection/TATE/TATE/TATE_TATE_T07820-001.jpg)