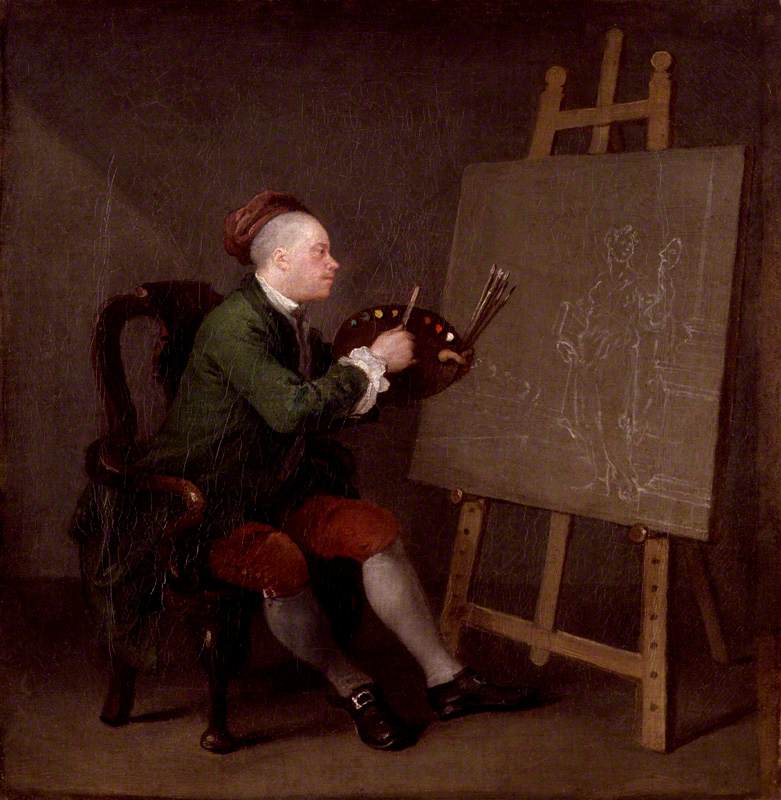

The artist, social commentator and polemicist William Hogarth (1697–1764) is best known for his satirical engravings and paintings of eighteenth-century Britain – a society he regarded as deeply flawed, uncivilised and debauched.

Hogarth lived and worked during the Georgian era, when alcohol played a central role in society – across the spectrum of class and wealth. The rising consumption of cheap gin from the 1700s – peaking between the 1720s and 1740s – resulted in an epidemic of binge drinking that historians now term the 'Gin Craze'.

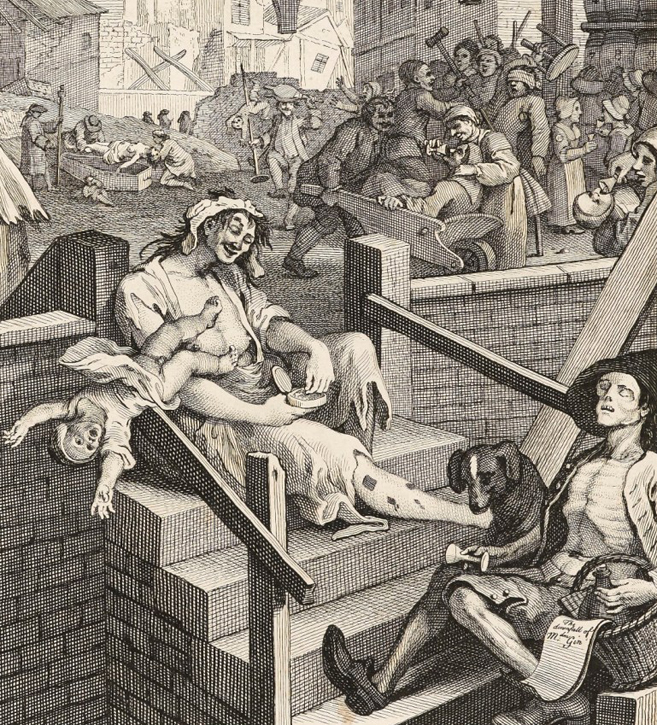

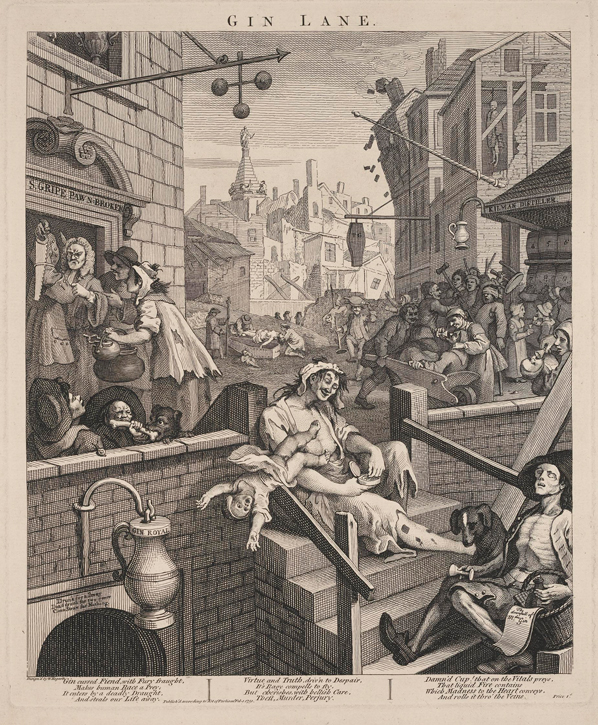

Gin Lane

(detail), 1751, engraving by William Hogarth (1697–1764)

This era of intoxication led to a number of dire health and social problems – including violence, insanity and often death – and sparked widespread moral outrage culminating in Parliament's involvement and the final Gin Act of 1751.

The unquenchable thirst for gin had become so immense by 1743, that the writer (and notorious alcoholic) Samuel Johnson once warned that to take away gin from the poorer classes would incite 'rebellion'. For the working classes, gin was a cheap and easy way to forget hunger, hardship, and was often safer to drink than the city's contaminated, sewage-infested water.

The tonic was nicknamed 'opium of the people', 'Madam Geneva' or 'mother's ruin', and Hogarth – who closely observed an increasingly drunk and idle society – documented the corrupting influence of gin better than any of his contemporaries.

Born in London in 1697, Hogarth came of age during the popularisation of gin in Britain. In the wake of political and religious conflict between Britain and France, the production of the spirit became a cheaper alternative to both French brandy and beer, which had previously been the dominant forms of alcohol in London's taverns and alehouses.

After the Glorious Revolution of 1688 which ushered in the reign of William of Orange as William III, Dutch gin had been imported into Britain and the juniper-based spirit (once called 'jenever' or 'genever') was soon being distilled and distributed across London. The drink was enjoyed by the poorest to the wealthiest members of society (including the royal family and famously Queen Anne).

Although gin was fashionable, its unregulated production meant that it was often distilled illegally in people's homes and harmful substitutes were mixed into the solution, additions that could cause severe health problems or, on occasion, death – for example, sulphuric acid, lime oil and turpentine.

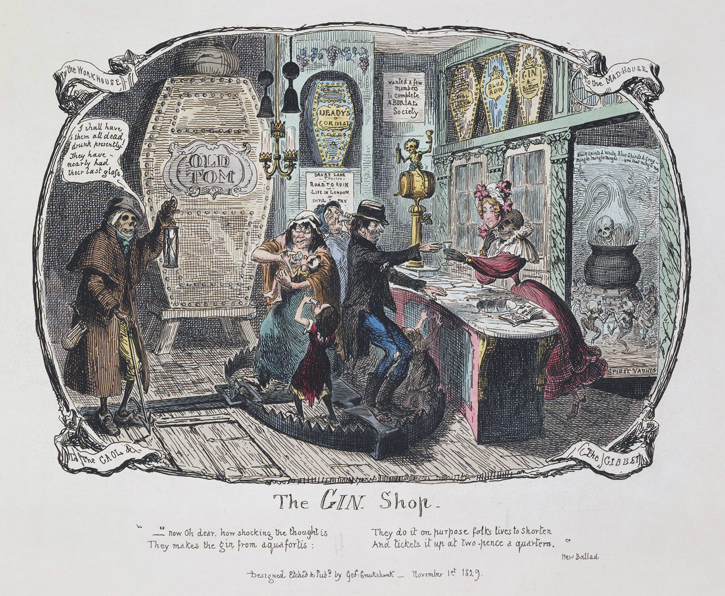

'The Gin Shop' from Scraps and Sketches

1829, etching by George Cruikshank (1792–1878)

The historian and author of Hogarth: A Life and a World, Jenny Uglow, writes that gin 'was sold everywhere – in grocer's shops and ship's chandlers. There was a bar in every building' and the typical signage above the gas-lit gin cellars of London read: 'Drunk for a penny; dead drunk for two pennies; clean straw for nothing'. By 1730, it is estimated that around 7,000 gin shops were functioning in London alone, serving around 10 million gallons of 'mother's ruin' every year.

In the 1720s and 1730s, Hogarth had made a name for himself, not only for being a successful 'conversation piece' painter but for openly condemning contemporary attitudes and tastes, particularly those of the wealthy elite.

From the 1730s onwards, Hogarth developed his modern morals, some of the most famous being A Harlot's Progress (1732), A Rake's Progress (1734), Marriage A-la-Mode (1743), Beer Street and Gin Lane (1751) and The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751). These series demonstrated that exorbitant drinking – and a society under the influence of alcohol and moral abandonment – would lead to misery and ruin.

A Harlot's Progress

1732, engraving by William Hogarth (1697–1764)

In the engraving above from A Harlot's Progress, Hogarth's naïve protagonist, Moll Hackabout (figure on the left), arrives in the city from the rural countryside, where she finds herself in the possession of Mother Needham – a notorious procuress.

Upon entering the city, Moll is quickly led astray and the series ends with her fall from grace and premature death. In Plate 6 of the series, titled Moll's Wake, her coffin becomes a makeshift tavern bar – Mother Needham feigns to mourn as she clutches to a flask of spirit.

During the early eighteenth century, a rise in crime and prostitution was blamed on gin overconsumption – women had become more dependent upon the drink (and therefore also pimps and madams if they had the misfortune to fall into prostitution). Women with 'loose morals' came to be closely associated with gin, as the drink could be served outside of alehouses, which were predominantly male domains. Among its other nicknames, gin became known as 'ladies' delight'.

In A Rake's Progress, Hogarth narrates the fall of his fictional character Tom Rakewell – the heir of a rich merchant who squanders all of his money on prostitutes, gambling and booze. In Orgy, Tom is visibly drunk at the Rose Tavern, Covent Garden, surrounded by prostitutes (with syphilis spots) who take advantage of his inebriation to pickpocket his watch.

A Rake's Progress: 6 – The Rake at the Gaming House

1734

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

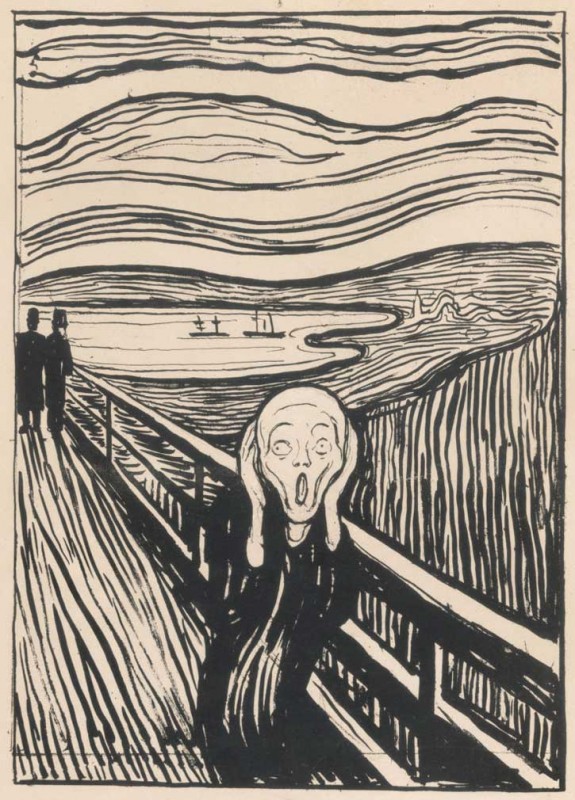

Despite his good fortune, Tom ends up in Fleet debtors' prison followed by Bedlam, where he lies naked, alone and insane. By depicting the downfall of the wealthy, Hogarth pointed out to his contemporaries that the excessive pursuits of pleasure could lead to the demise of anyone, including members of 'polite society'. A Rake's Progress exposed the hypocrisies of the wealthy, who often attached the gin epidemic solely to the poorer classes.

The biographer of Samuel Johnson, James Boswell, recorded in his diaries in 1790 that regular excessive drinking in 'polite company' would often result in 'total oblivion', perhaps not unlike the scene above captured by Hogarth.

Hogarth's two prints Beer Street and Gin Lane were created to be viewed together in 1751, in support of the Gin Act of the same year. The Act (the eighth time Parliament had tried to curtail the production of gin) was directly in response to Henry Fielding's Enquiry into the causes of the late increase of Robbers, which had highlighted the connection between gin drinking and crime:

'A new kind of drunkenness, unknown to our ancestors, is lately sprung up among us, and which if not put a stop to, will infallibly destroy a great part of the inferior people. The drunkenness I here intend is... by this poison called Gin.'

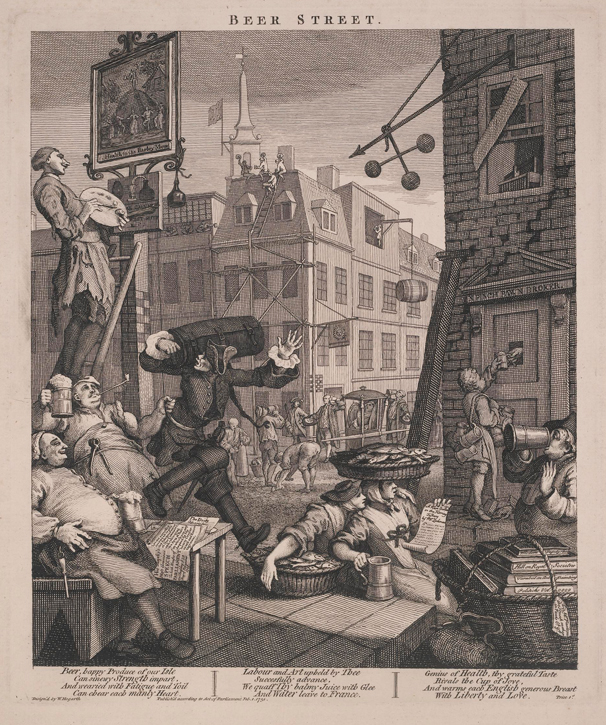

The first of the two prints, Beer Street, reveals a harmonious street scene, in which civilians appear jolly and healthy, albeit overweight. Baskets overflow with food and men and women take pleasure in flirtation.

Beer Street

1751, engraving by William Hogarth (1697–1764)

In contrast, Gin Lane presents a scene of urban chaos. Desolation unfolds as gin-crazed Londoners enter into a brawl in the area of St Giles – a location of ill-repute in Bloomsbury that was known for its brothels and gin shops.

Gin Lane

1751, engraving by William Hogarth (1697–1764)

In the foreground, a drunk woman (the embodiment of 'Mother Gin') fails to notice that her baby is tumbling into a gin-vault below, as she absentmindedly sniffs on tobacco. At her feet, a skeletal man lies in a drunken stupor, loosely clutching a bottle of gin. Above his emaciated head, a young mother pours gin into her toddler's gaping mouth.

Real events that turned into urban legends gave rise to the idea that gin turned mothers away from their responsibilities. In 1734, a woman named Judith Dufour scandalised society after she strangled her two-year-old son and sold his clothes for gin.

Daniel Defoe, who had previously campaigned for the liberalisation of gin distilling, complained that drunken mothers were threatening to produce a 'fine spindle-shanked generation' of children. In 1726, the Tavern Scuffle had declared: 'when a woman once takes to drinking, I give her over for lost, she then neglects husband, children, family, and all for her darling liquor.' The exorbitant gin-drinking habits of women were so bad that in 1750, the writer Eliza Haywood published the popular book A Present for Women Addicted to Drinking.

More than any other artist of his time, Hogarth immortalised London's drunk and debauched era of the Gin Craze through satirical engravings. However, he captured the follies of those addicted to gin with compassion as well as mockery and condescension – understanding that society's deprivation and depravity led the masses to become victims of the drink.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK