(Born Pieve di Cadore, c.1480/5; died Venice, 27 August 1576). The greatest painter of the Venetian School and one of the supreme figures of world art. In the course of a very long and highly prolific career he dominated Venice's art during its golden age and also worked for many illustrious patrons outside the city; his paintings have had a profound and enduring influence on European art. Most of his career is well documented, but his early years are somewhat obscure and his date of birth has long been a subject of scholarly debate, for the evidence concerning it is contradictory; certainly he was very old when he died, although perhaps not quite as old as some accounts suggest (traditionally he lived to be 99). He was probably a pupil of Giovanni Bellini, and in his early work he came under the spell of Giorgione, with whom he had a close relationship. In 1508 (the first secure point in his career) they collaborated on the external fresco decoration (destroyed) of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi (German warehouse) in Venice, and after Giorgione's early death in 1510 Titian is said to have completed a number of paintings that his friend left unfinished. The authorship of certain works (some of them famous) is still disputed between them.

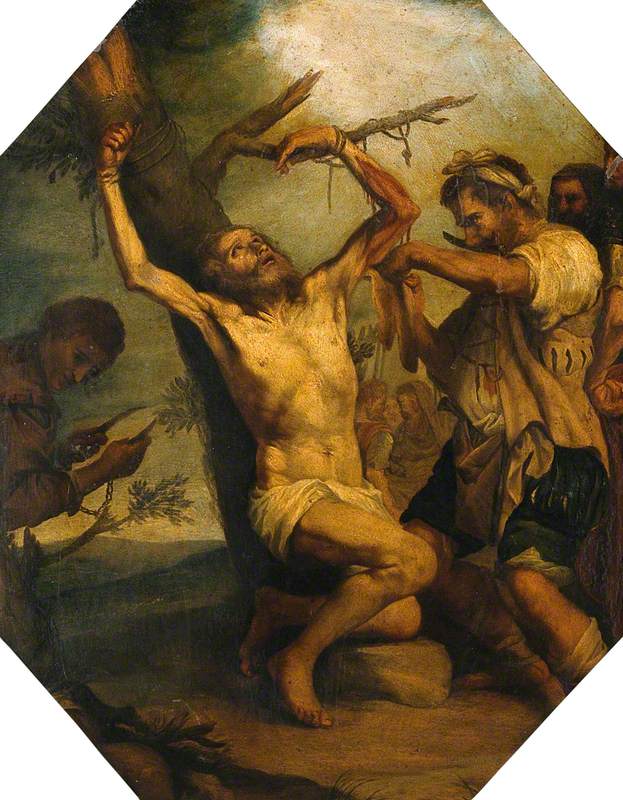

In the second decade of the century Titian moved away from Giorgione's dreamily romantic style and developed a much more robust manner of his own. There is still a good deal of Giorgione's enigmatic poetry in the allegorical Sacred and Profane Love (c.1514, Borghese Gal., Rome), but it is tempered by worldliness, and Titian's style soon became much more dynamic. This is seen particularly clearly in the work that more than any other stamped his authority in Venice—the huge altarpiece of the Assumption of the Virgin (1516–18, S. Maria dei Frari, Venice). It is one of the largest pictures he ever painted and one of the greatest, matching the achievements of his most illustrious contemporaries in Rome in grandeur of form and surpassing them in splendour of colour. The soaring movement of the Virgin, rising from the closely packed group of Apostles towards the hovering figure of God the Father, looks forward to the Baroque. Similar qualities are seen in Titian's two most famous altarpieces of the 1520s: the Virgin and Child with Saints and Members of the Pesaro Family (the Pesaro Altarpiece) (1519–26, S. Maria dei Frari), a bold diagonal composition of great magnificence, and the Death of St Peter Martyr (completed 1530), which he painted for the church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice, having defeated Palma Vecchio and Pordenone in competition for the commission. The painting was destroyed by fire in 1867, but it is known through copies and engravings: trees and figures together form a violent centrifugal composition appropriate to the action, and Vasari described it as ‘the most celebrated, the greatest work…that Titian has ever done’.

The young Titian had important secular as well as ecclesiastical commissions, notably a set of three mythological pictures (1518–23) for Alfonso d' Este, his first princely patron—the Worship of Venus, the Bacchanal (both in the Prado, Madrid), and Bacchus and Ariadne (NG, London). He was also busy as a portraitist. Many of his early portraits are of unknown sitters, as with the exquisite Man with a Glove (c.1520, Louvre, Paris), but later he painted some of the most famous personalities of the day.

Titian's success brought him a substantial income and from 1531 he lived in a palatial house in Venice, with gardens overlooking the lagoon. In 1533 the Emperor Charles V (see Habsburg) appointed him court painter and elevated him to the rank of count palatine and Knight of the Golden Spur. This was an unprecedented honour for a painter, and Ridolfi tells a revealing anecdote concerning the respect Titian was accorded even by the emperor himself: Titian dropped a brush and when Charles picked it up for him he protested ‘Sire, I am not worthy of such a servant’, to which the emperor replied ‘Titian is worthy to be served by Caesar.’ Although he had probably had a fairly basic education (he knew no Latin), he does indeed seem to have been at ease in the elevated society of his patrons: contemporary accounts say he was well-mannered and a good conversationalist, and his best friend was the famous poet Pietro Aretino. Titian had first met the emperor in 1530, when he was crowned in Bologna. Although he made several short visits such as this to towns in northern Italy, he was reluctant to journey far from Venice and he turned down Charles's invitation to go to Spain to paint portraits of the royal family. In the 1540s, however, he overcame his resistance to travelling long distances, visiting Rome in 1545–6 at the invitation of Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese) and then Augsburg in Germany in 1548 to work at Charles's court. He returned to Augsburg in 1550–1.

His work in Rome included a celebrated portrait of the pope with his grandsons, Cardinal Alessandro and Ottavio Farnese (Mus. di Capodimonte, Naples), and he brought with him a painting of Danaë (c.1544–5, Mus. di Capodimonte), previously commissioned by the cardinal. It is one of his most gloriously sensuous treatments of the female nude, and a papal legate writing to the cardinal in 1544 stressed its overtly erotic character by comparing it with Titian's own slightly earlier Venus of Urbino (1538, Uffizi, Florence): ‘the nude that Your Reverence saw…in the apartment of the Duke of Urbino [Guidobaldo della Rovere] looks like a nun compared with this one.’ According to Vasari, Michelangelo praised the colouring of Danaë but found fault with the drawing.

Titian's work in Augsburg included Charles V on Horseback (1548, Prado, Madrid), the largest and grandest of all his portraits.The greatest patron of Titian's later career was Charles's son, Philip II of Spain, whom he first met in 1549 in Milan. Initially Philip was unimpressed with Titian's work, finding his brushwork too broad, but he came to admire him above all other painters, and eventually—rather than commissioning specific works from him—he was content to accept whatever the master cared to send him. Like his father, Philip was intensely devout, and Titian's work for him included religious pictures as well as portraits. However, the most famous works he painted for him are a series of seven erotic mythological subjects (c.1550–c.1565) based (sometimes loosely) on Ovid's Metamorphoses. In probable chronological sequence, these are: Danaë (a variant of the earlier picture for Cardinal Farnese) and Venus and Adonis (Prado), Perseus and Andromeda (Wallace Coll., London), Diana and Actaeon and Diana and Calisto (Ellesmere Coll., on loan to NG of Scotland), the Rape of Europa (Gardner Mus., Boston), and the Death of Actaeon (NG, London). Titian referred to these pictures as poesie (poems), and they are indeed highly poetic visions of distant worlds, quite different from the sensual realities of his earlier mythological paintings. By this time his style had changed greatly from that of his youth, becoming freer and riper, with a growing emphasis on inner feeling rather than external drama; his colour ranges from shimmering delicacy to fiery intensity, and his brushwork is loose and almost impressionistic. It has been argued that the extreme freedom of handling in some of his final works is a result of their being unfinished and perhaps partly a consequence of failing eyesight. The situation is complicated by the fact that in his later career Titian is known to have made extensive use of assistants, among them his brother Francesco Vecellio (c.1490–1559/60) and his son Orazio Vecellio (1525–76). Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that Titian's final works include some of his most sublime creations, and his career ends with the awe-inspiring Pietà (c.1575–6, Accademia, Venice), which is said to have been intended for his own tomb and was evidently finished after his death by Palma Giovane.Titian was recognized as a towering genius in his own time (Lomazzo described him as ‘the sun amidst small stars not only among the Italians but all the painters of the world’) and his reputation has never declined (it has been commonplace for centuries to describe him as the greatest of all colourists).

He was supreme in every major branch of painting practised in his time and his achievements were so varied—ranging from the joyous evocation of pagan antiquity in his early mythologies to the depths of tragedy in his late religious paintings—that he has been an inspiration to artists of very different character. Van Dyck, Poussin, Rubens, and Velázquez are among the painters who have particularly revered him. In many subjects he set patterns that were followed by generations of artists, particularly in portraiture: more than anyone else he was responsible for widening the scope of portraiture beyond the head-and-shoulders type that prevailed in the 15th century, not only by popularizing the half-length and the full-length, but also by varying his poses and introducing accessories such as a dog, a book, or a classical column.

In technique he was just as influential, for he was the first to show the limitless expressive potential of oil paint, creating a vibrant pictorial surface in which the artist's personal ‘handwriting’ is evident in every touch of the brush. According to Palma Giovane, ‘in the final stages he worked more with his fingers than with his brush’, and Vasari wrote that his late works ‘are executed with bold, sweeping strokes, and in patches of colour, with the result that they cannot be viewed from near by, but appear perfect at a distance…The method he used is judicious, beautiful, and astonishing, for it makes pictures appear alive and painted with great art, but it conceals the labour that has gone into them.’

Titian's greatness as an artist, it appears, was not matched by his character, for he was notoriously avaricious. In spite of his wealth and status, he claimed he was impoverished, and Erwin Panofsky comments that ‘his tax declaration of 1566…would land him in jail today’. However, he was lavish in his hospitality towards his friends, notably Pietro Aretino and the sculptor and architect Jacopo Sansovino. These three were so close that they were known in Venice as the triumvirate, and they used their influence with their respective patrons to further each other's careers.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)