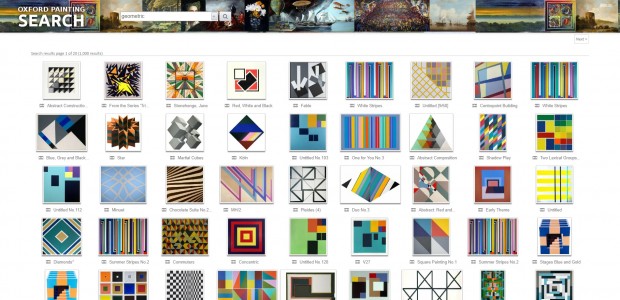

Typing Guido Reni into Art UK returns 104 images, of which seven appear to be of the same picture, Reni's Salome with the Head of John the Baptist.

Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist

Guido Reni (1575–1642) (after)

This is not a flawed algorithm, as examination of each reveals them to be seven different copies of Reni's painting from Palazzo Corsini in Rome, housed in collections as diverse as The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology in Oxford and Barrow-in-Furness Borough Council.

The same pattern is repeated when searching for other Italian painters of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Raphael returns nearly 30 Madonna della seddias; Correggio, six copies of the Madonna and Child with Rabbit (also known as La zingarella); and Titian, three replicas of his Venus Blindfolding Cupid.

Principally dating from the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, these copies are rarely on public display and have received comparatively little attention from art historians and curators. The work of Art UK presents an opportunity to consider why so many copies were made and why they are so numerous in our public collections, and may perhaps even prompt reconsideration of their status.

At its simplest level copying was the acknowledged method for learning to paint from the sixteenth until the mid-nineteenth centuries. At most European academies copying was considered a central element of artistic training; it was one of the mandatory exercises (or envois) undertaken by winners of the Prix de Rome at the French Académie, viewed as essential for teaching the young painter how to manage a composition and – after an initial training rooted in drawing – facility in handling colour.

Britain lacked the same structures before the foundation of the Royal Academy in 1768, but copying was nevertheless key to most painters' early careers, featuring as a reality in productive studios. Successful portraitists replicated their compositions as a matter of course, frequently employing assistants specifically for the purpose. Examination of almost any studio sale from the first half of the eighteenth century reveals large numbers of copies which must have been both stock and studio furnishing.

The commercial imperative to copy was compounded by the taste of British patrons. From early in the eighteenth century it was generally understood that collectors would prefer a good copy of a famous picture to an indifferent original; to this end, a number of artists worked specifically as professional copyists. An artist such as Francis Harding, for example, made a career imitating the work of the fashionable Italian painter Giovanni Paolo Panini.

The Interior of St Peter's at Rome

(after Giovanni Paolo Panini) c.1730–1742

Francis Harding (active c.1730–c.1766) (attributed to)

In 1803 Edward Edwards observed of early eighteenth-century interiors: 'frequently the compartments over the chimney and doors, were filled with some kind of picture, which was seldom the original work of any master, but commonly the production of some practical copyist, who subsisted by manufacturing such decorative pieces.' Perhaps some of the 67 canvases listed as by Panini on Art UK are actually by a 'practical copyist' such as Harding?

Rome: The Interior of St Peter's

before 1742

Giovanni Paolo Panini (1691–1765)

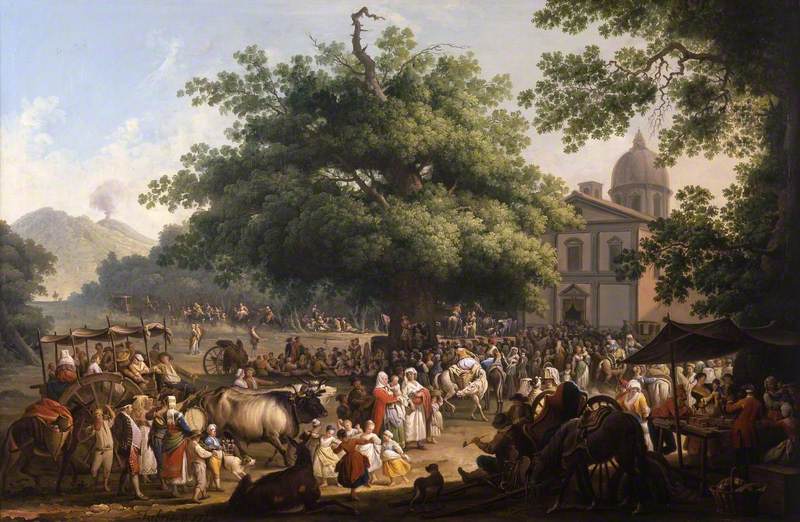

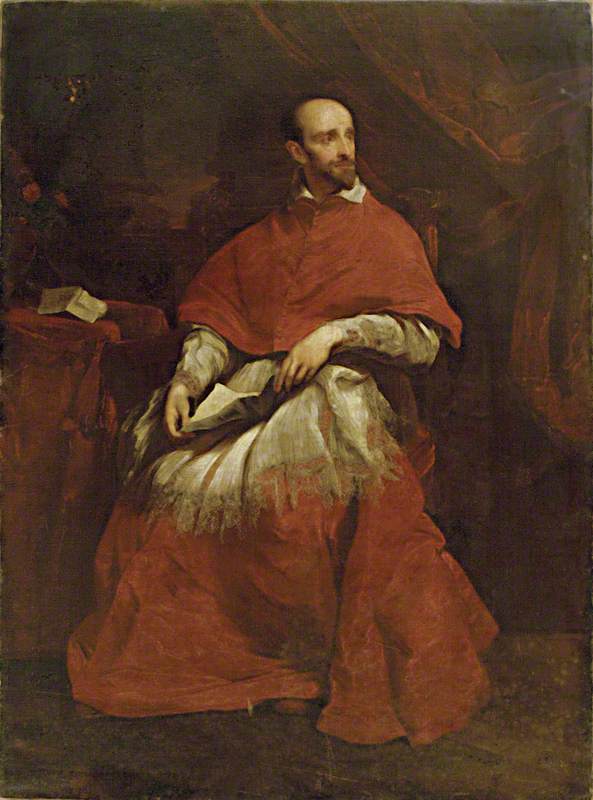

The desirability of copies, particularly of an exiguous group of Italian paintings, meant that for British artists travelling in Italy, copying was not only an educational exercise, but financially expedient. Art UK has helped publish some unexpected copies made by painters abroad. Edward Penny for example, the first professor of painting at the Royal Academy, when visiting Florence in 1741 made a fine, full-size copy of Anthony van Dyck's portrait of Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio now at The Ashmolean.

Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio

(copy after Anthony van Dyck) 1741

Edward Penny (1714–1791)

Benjamin West, travelling 20 years later, arrived in Rome with an open commission to complete copies for his American patrons, Lieutenant Governor James Hamilton and Chief Justice William Allen, as partial recompense for their financial support. In all he dispatched six copies back to Philadelphia of which four are now in the Ferens Art Gallery, Hull including a fine version of Guido Reni's Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist.

Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist

(copy after Guido Reni) 1763

Benjamin West (1738–1820)

The desirability of copies as Grand Tour souvenirs meant that they often featured prominently in decorative schemes. The Victoria Art Gallery in Bath, houses two large copies of Guido Reni's The Rape of Helen and Guercino's The Death of Dido from Palazzo Spada in Rome.

The copies, by an unknown hand, formed part of the decoration of the Saloon at Stourhead which were thought lost in a fire until their recent rediscovery in Bath.

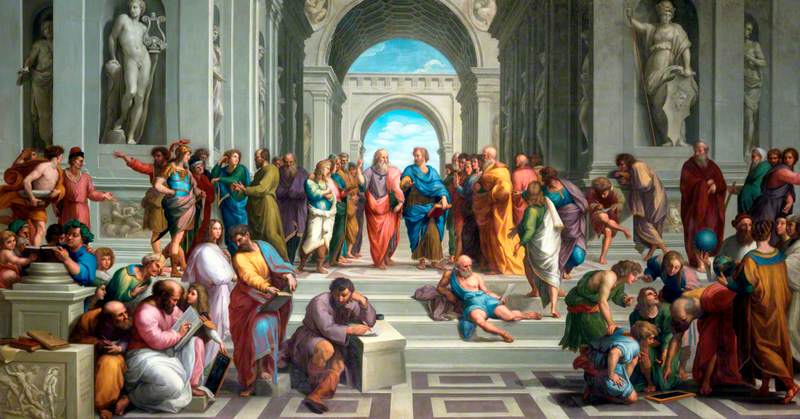

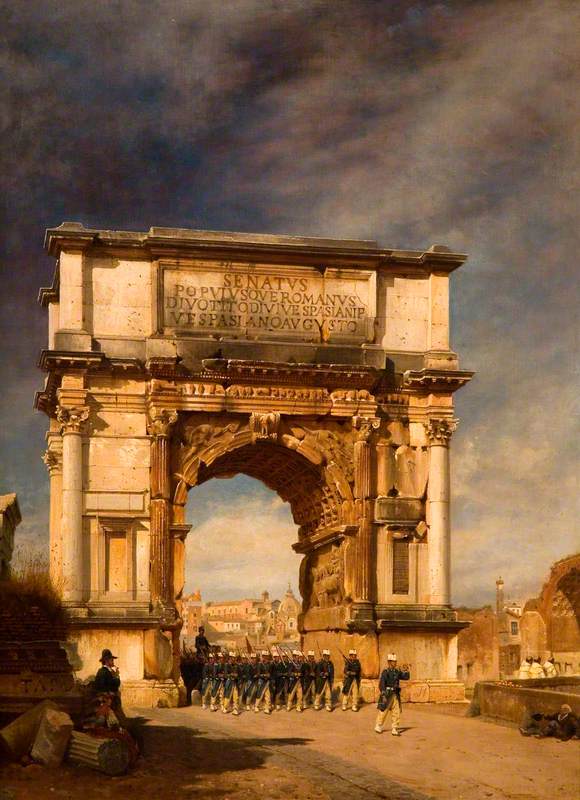

Perhaps the most splendid example of the programmatic use of copies, was the gallery at Northumberland House, whilst four of the copies are now in Venice, the fifth, a version of the School of Athens by Anton Raphael Mengs, hangs in the cast court of the V&A.

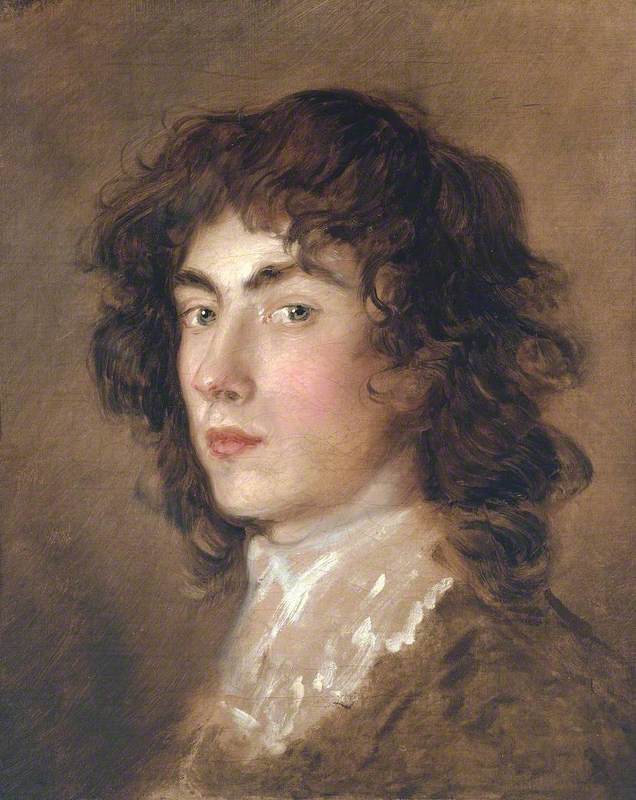

There was a reluctance to officially encourage students to copy in Britain. Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the Royal Academy, in his second Discourse delivered to the students of the Academy in 1770, stated that he considered: 'general copying as a delusive kind of industry.' This official coolness did not prevent painters copying as both a very personal exercise in understanding the work of a favourite master – for example Thomas Gainsborough's masterful essay after Rubens preserved at Gainsborough's House – or as a practical exercise.

Descent from the Cross

(after Peter Paul Rubens) c.1765–1770

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

It was not until the British Institution began an annual exhibition showing Old Masters in 1813 that artists had a space in which to copy in London and it was not until 1816, with the foundation of the Painting School, that the Royal Academy finally encouraged the practice amongst its students. Evidence of both these enterprises can be found in public collections: surely William Hilton II's copy of Rubens' Samson and Delilah at the V&A for example was painted when the original was lent to the Academy?

Samson and Delilah

(after Anthony van Dyck) c.1810–1830

William Hilton (1786–1839)

Without inscriptions, signatures or provenance details it is often difficult to establish precisely who a copy is by, but the work of Art UK offers a great tool for exploring neglected paintings and perhaps with more work the authors of more copies might be revealed.

Jonny Yarker, scholar of British painting and the Grand Tour