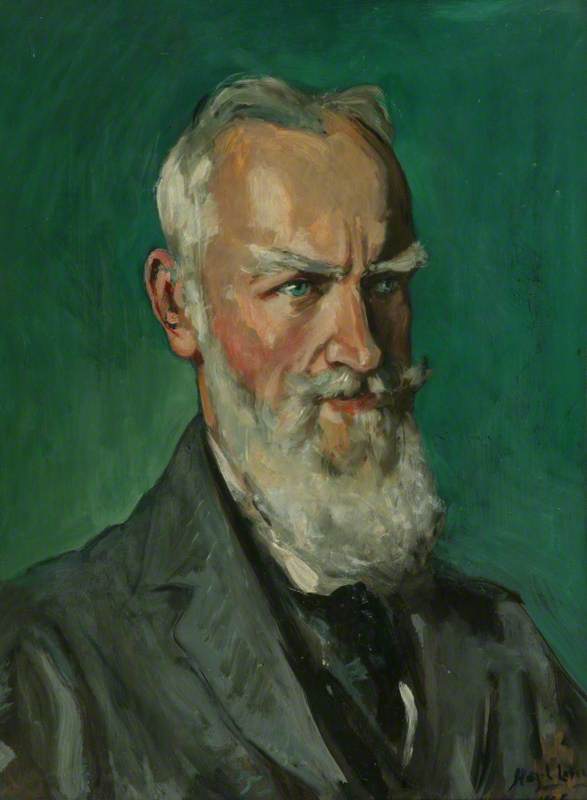

'The revelation of personal sensibility, the quality of the sketch... is overlaid and smothered by labour.' – Kenneth Clark

Image credit: National Museums NI

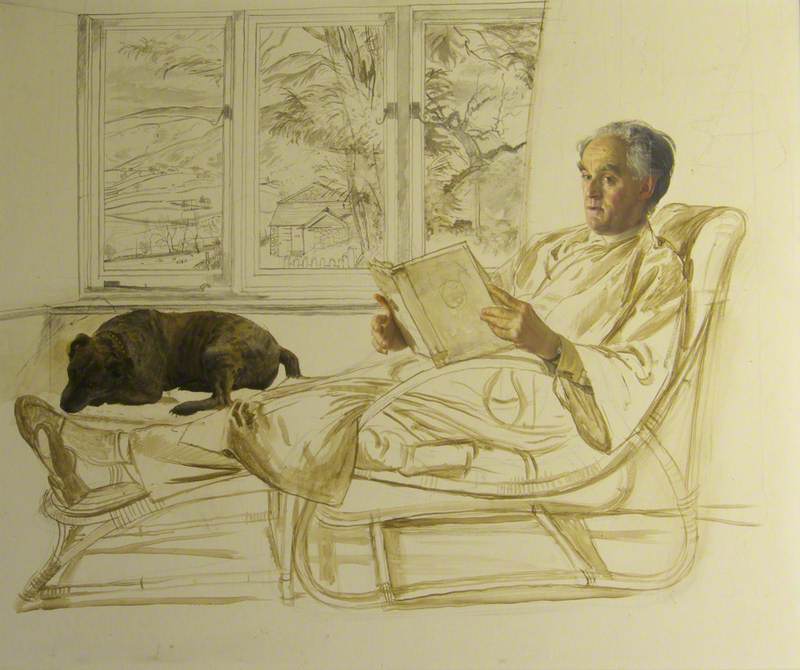

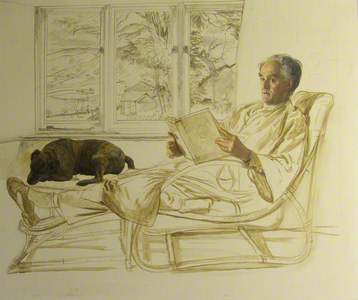

Sir William Orpen (1878–1931) (unfinished sketch) 1929–1931

Francis Edwin Hodge (1882–1949)

National Museums NIWhen is an artwork truly finished?

And why, despite the many hours an artist spends before a canvas perfecting a painting, are we sometimes more attracted to the incomplete version?

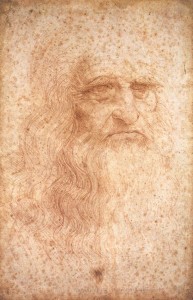

Whether left unfinished deliberately or abandoned because of illness, tragedy, or even death, we can still learn about an artist's creative process by looking at their incomplete works. For example, it is well known that many of Leonardo da Vinci's paintings were left unfinished because he was a notorious procrastinator or, at least, he was always jumping from one project to the next.

Or take the great Venetian painter Titian as an example, who left many of his works incomplete in the final decade before his death. Never satisfied with his painting The Flaying of Marsyas, he continued to work on the large-scale canvas for over a decade.

Let's explore Art UK to consider the everlasting allure of unfinished artwork.

Proximity to the artist

We revel in the incomplete artwork because, for some reason, it allows us to feel closer to the artist.

The curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibition 'Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible' Kelly Baum said:

'An unfinished picture is almost like an X-ray, which allows you to see beyond the surface of the painting.'

Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist 1528–1537

Perino del Vaga (1501–1547)

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)In agreement with her, there is something curiously intimate, or even invasive about seeing an unfinished work. Every visible brushstroke, line of under-drawing, or smudge of a fingerprint allows us to feel as if we are being let into an artist's secret world. It's almost as if we are sitting in the same room as the artist, before an undeveloped work that demands a bold decision, careful application and patience. The artist is exposed and rendered vulnerable. Yet somehow they become more relatable, more fallible – more human.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

The Virgin and Child with Saint John and Angels ('The Manchester Madonna') about 1497

Michelangelo (1475–1564)

The National Gallery, LondonA perfect example is this painting by Michelangelo. Known as 'The Manchester Madonna', the tempera on poplar shows the Virgin and Child next to Saint John and angels. Left unfinished in the late 1490s, the work reveals a great deal about Michelangelo's decision-making. Art historians noticed that he worked on individual figures one by one, rather than approaching the work as a large-scale composition. It also gave specialists new insight into how Michelangelo and other Renaissance painters used green pigment, or 'terra verde', as the base tone for flesh.

This can also be detected in this unfinished Michelangelo work of Christ below.

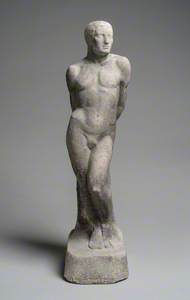

The 'non-finito' work

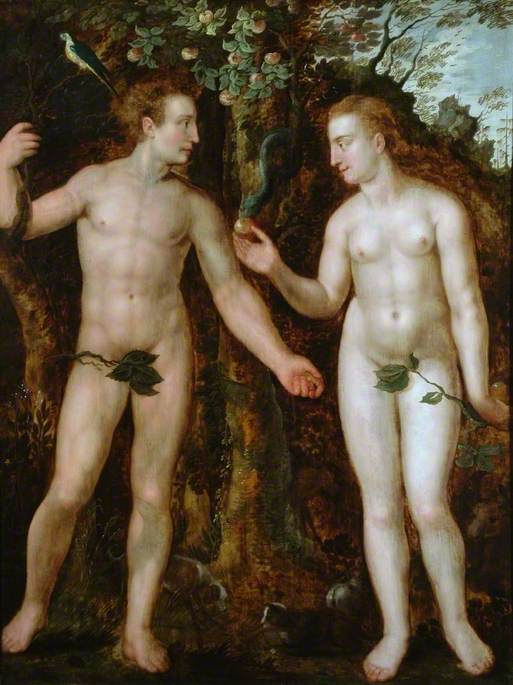

The unfinished works by Renaissance Masters – Donatello, Leonardo and Michelangelo – set a new precedent for artists in the sixteenth century and beyond. It became fashionable to leave works incomplete, so much so, that it became an aesthetic term 'non-finito' (literally meaning 'not finished').

The Italian Renaissance art historian Giorgio Vasari once observed that Michelangelo's works 'were of such a nature that he found it impossible to express such grandiose and awesome conceptions with his hands, and he often abandoned his works, or rather ruined many of them... for fear that he might seem less than perfect.'

Titian also left this work unfinished in the decade before his death, or at least, he appears to have mimicked the non-finito style, according to Alistair Sooke. The brushstrokes are remarkably loose and expressionistic, diverging from his previously more polished approach to painting.

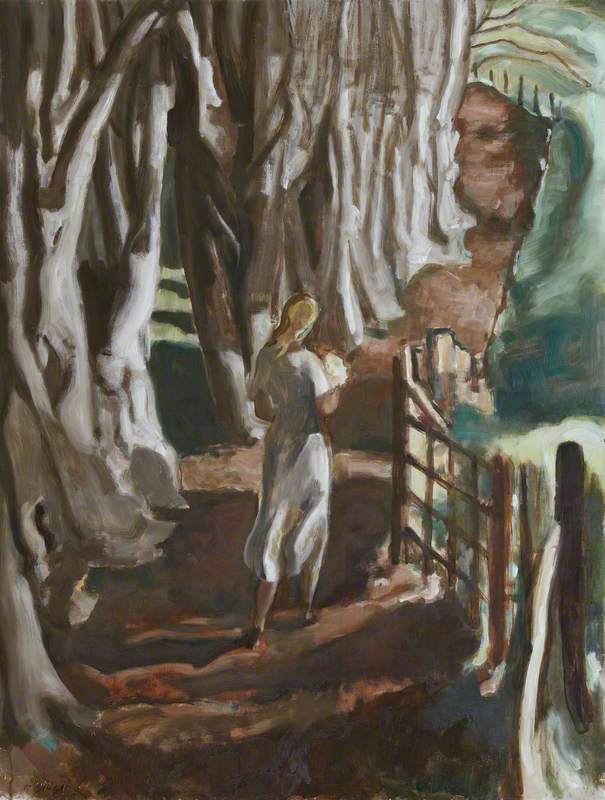

The problem of perfection

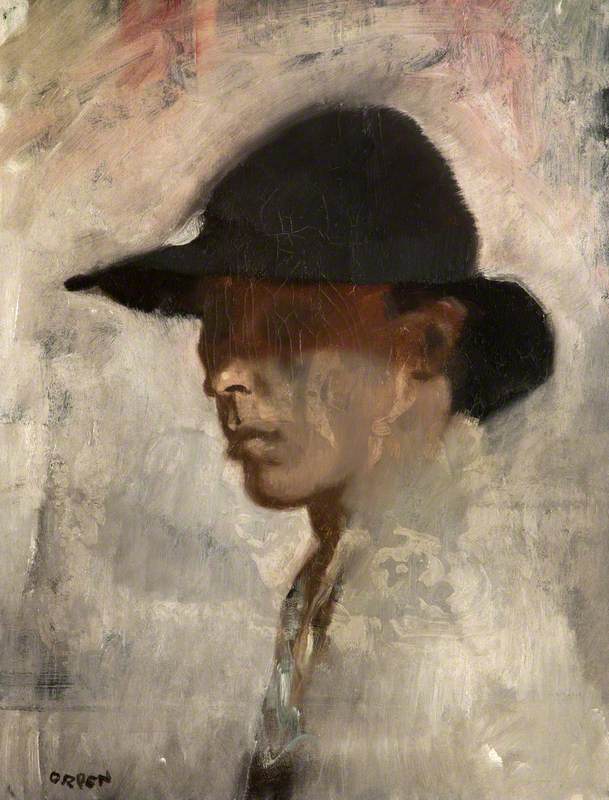

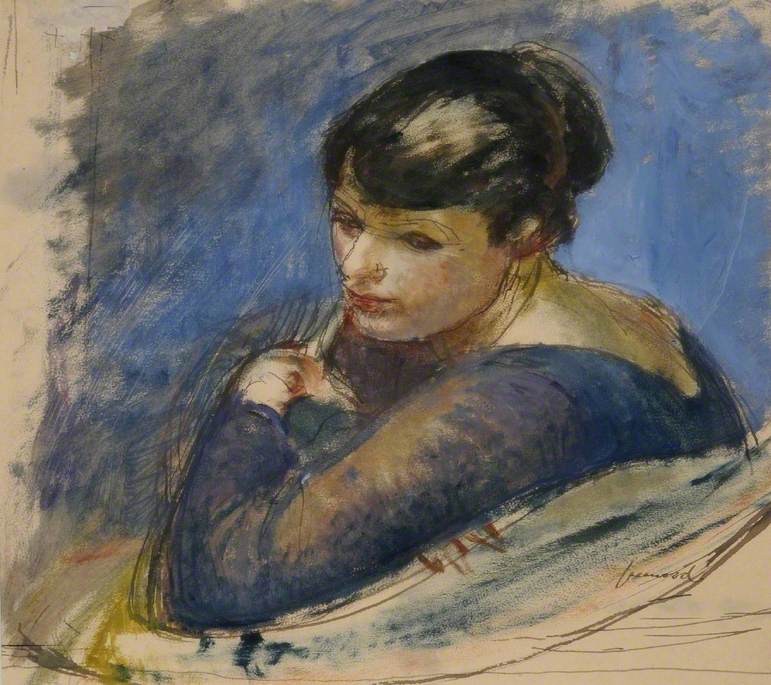

Arguably, an unfinished or incomplete work holds a unique kind of beauty, one which can feel more painterly or raw, even authentic. For example, Sydney Earnshaw Greenwood's Portrait of the Artist's Wife is fleeting and sketchy, though it captures a sense of movement, character and the inner essence of the sitter.

Image credit: University of Hull Art Collection

Sydney Earnshaw Greenwood (1887–1947)

University of Hull Art CollectionSo why are we so fixated with the 'perfect' or 'ideal'?

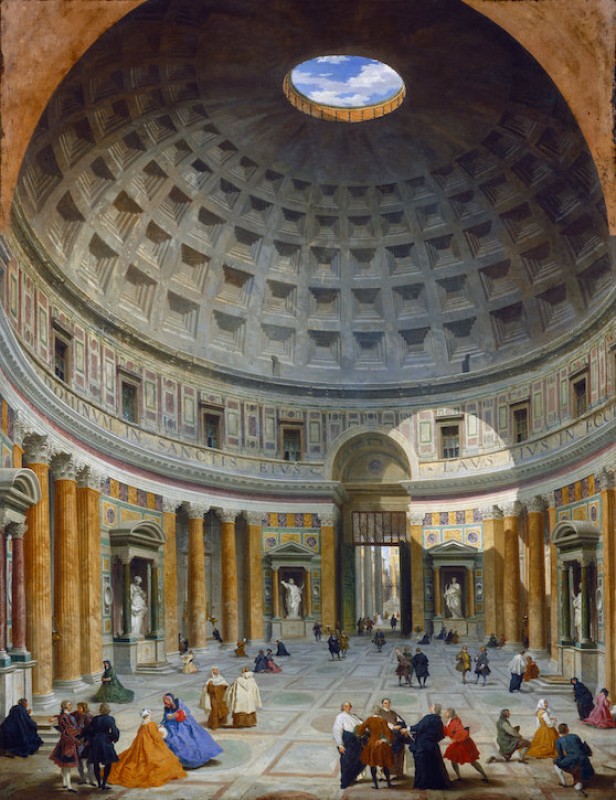

In ancient Greece, philosophers like Plato believed that art was 'mimesis', meaning it was an imitation of the divine. Plato taught that art is merely an illusion, one which can be dangerous if it appears too real. Nevertheless, in the centuries following, artists continued to strive for the kind of ideals once set out in ancient Greek art, following aesthetic principles that were believed to be the divine proportions and ratios for architecture and the human body.

During the Renaissance, the school of thought known as Neo-Platonism flourished, and Humanist artists and philosophers incorporated the teachings of Plotinus, Plato, Aristotle and other Greek philosophers into their work. The Renaissance strivings for visual perfection were rooted in a similar desire that characterised the ancient world. Art historian Vasari perpetuated the expectation for god-like perfection or 'genius' in the work of the artist. He once praised the artist Andrea del Sarto by claiming his work was 'free from errors, and absolutely perfect in every respect.'

It could be argued that the modern sculptor Auguste Rodin was returning to the classical tradition of presenting the non-finito work, although his idea of the sculptural 'fragment', seen particularly in works such as La Pensée (1895), was actually quite new and shocking. While he revered antiquity, he wanted his own sculpture to be radically modern. Consequently, many of his works embrace naturalism over idealism.

Unexpected tragedy

Unfinished works can also tell us more about significant moments in an artist's personal life or their inner psychological state. Many artworks throughout history were left incomplete simply because the artist became sick or died before finishing the work.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Three Men and a Boy about 1647-8

Antoine Le Nain (c.1588–1648) and Louis Le Nain (c.1593–1648) and Mathieu Le Nain (1607–1677)

The National Gallery, LondonThis painting by three seventeenth-century French brothers, known as 'Le Nain brothers' (Antoine Le Nain, Louis Le Nain, and Mathieu Le Nain) was left incomplete between 1647 and 1648.

The brothers worked in collaboration, though specialists have never been able to distinguish between their individual hands. Both Antoine and Louis died in 1648, which may be one reason why the painting was left unfinished. In retrospect, the painting becomes an embodiment of loss and absence.

Take Your Son, Sir! is another example of a work that was left unfinished due to the psychological strife taking place in the artist's life. Ford Maddox Brown created this painting depicting his second wife, Emma, and their newborn son, Arther Gabriel. He started the painting when Emma was pregnant and abandoned it in 1857 when his son died at only 10 months old.

The immediacy of painting

Au Bal – Marguerite de Conflans en toilette de bal 1870–1880

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

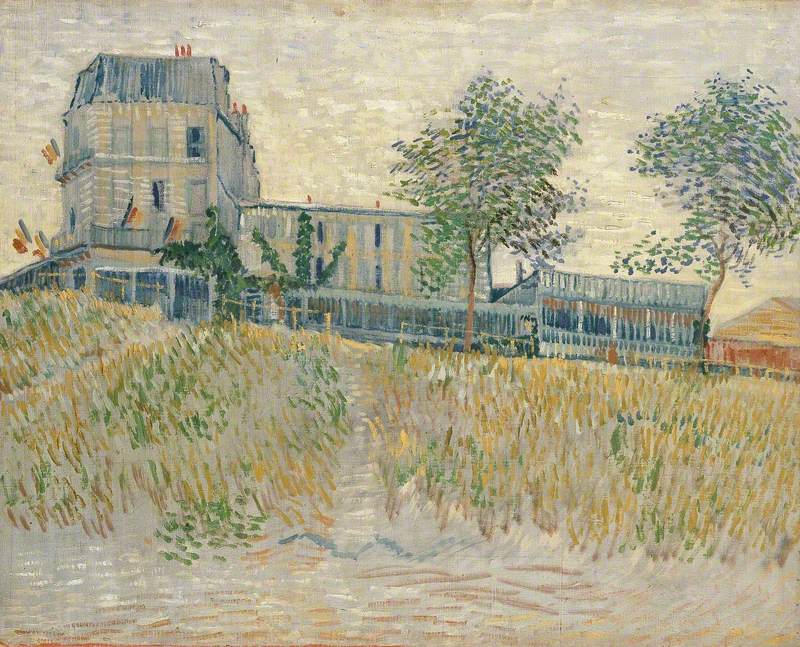

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)With the advent of Impressionism in the nineteenth century, artists turned towards a style of painting that aimed to capture fleeting moments in time. Their work sought to imprint an impression of light, the sensibility of the artist rather than an accurate representation of a particular subject or object. A change of taste in the nineteenth century led to the development of the 'painterly' style, popularised by the Swiss art historian Heinrich Wölfflin. He advocated for a non-academic approach to painting that left visible brushstrokes, a looser application and impulsive use of colour.

This painterly style stood in direct juxtaposition to the academic, polished or highly 'finished' looking work. Instead it embraced a rougher, sketchier form often including an impasto application of paint.

In 1874, at the first organised Impressionist exhibition in Paris, artists Claude Monet, Edgar Degas and Camille Pissarro (amongst others) exhibited work. Critic Louis Leroy accidentally coined the name 'Impressionism' when he criticised Monet's Impression, soleil levant.

'Impression I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it – and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape.' – Louis Leroy in Le Charivari, 25th April 1874

Image credit: National Trust Images

Pont de Londres (Charing Cross Bridge, London) 1902

Claude Monet (1840–1926)

National Trust, ChartwellThe cult of the unfinished artwork has re-emerged at different points in history and is arguably a reflection of changing tastes and aesthetics, but also the mindset of artists.

Though many artists never intended for us to see an incomplete product of their oeuvre, we can still appreciate these incomplete and imperfect visual forms, which tell us so much about the inner psyche of their creator.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK