In Tom Phillips' 1986 portrait of Iris Murdoch, the philosopher-novelist gazes out of an unseen window. She is still in a manner that goes beyond the necessary posed-ness of portraits – a stillness distilled in the flat, scrupulous brushwork of her face and foreground. But the background is another thing altogether. In the half-dark behind her is an impressionistic bustle of activity. A man kneels with a knife in his hand, intent on an object hanging before him.

For those familiar with the original, the scene glimpsed behind Murdoch resolves into a familiar image: Titian's The Flaying of Marsyas. Painted in the years before his death in 1576, the picture is one of the long series of works in which Titian depicted scenes from the ancient Roman poet Ovid's narrative poem, Metamorphoses. The subject is the fate of the satyr Marsyas, foolish enough to challenge the god Apollo to a musical contest. His reward was to be flayed alive.

The Flaying of Marsyas

c.1570–c.1576, oil on canvas by Titian (1490–1576)

In an epic filled with divine cruelty, it is a scene of remarkable gruesomeness. Ovid's description of the punishment, summoned in just a few lines, seems to envisage Apollo skinning the satyr as a butcher might skin a goat or sheep: by starting with a knife and then pulling back the skin by hand, inch by inch. 'Why are you tearing me from myself?' – quid me mihi detrahis? – Marsyas cries out; Apollo gives no answer except continuing. While the satyr screams,

the skin was torn off the surface of his body,

until he was nothing but a wound; blood flows all over,

his muscles are uncovered and exposed, his shivering veins

without skin shake; you could number the guts twitching

and the innards shining through his chest.

It is a terrifying image. Titian and Phillips offer something both calmer and stranger. Their Apollo kneels calm as a surgeon, one hand steadying his strung-up victim, the other delicately wielding the knife. The satyr's gaze meets the viewer's in silent dismay.

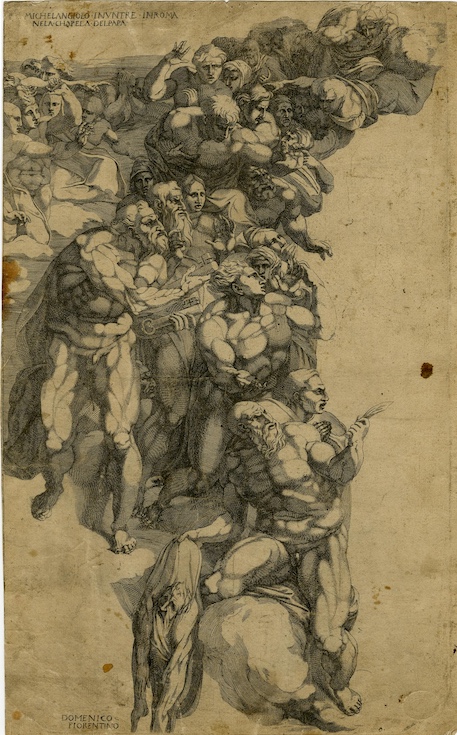

Study of 'The Flaying of Marsyas'

(after Titian) 1985–1986

Tom Phillips (1937–2022)

Murdoch and Phillips bonded over the painting in 1983 when they first met, both fresh from seeing it for the first time. In a 1984 interview for the BBC, Murdoch said the work had 'something to do with human life and all its ambiguities and all its horrors and terrors and misery and at the same time there’s something beautiful… and something also to do with the entry of the spiritual into the human situation.'

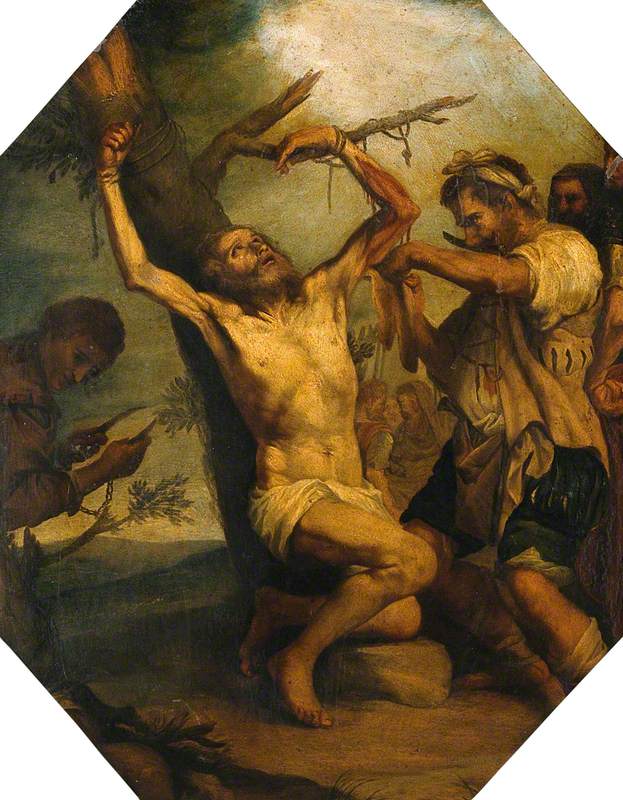

The Flaying of Marsyas

1616-18

Domenichino (1581–1641) (and assistants)

For those of a less philosophical turn of mind, it can be hard to get beyond the horror that comes from empathising with what such a fate must feel like. Artists who came to the subject of Marsyas faced a double challenge. Perhaps the most gruesome death imaginable, flaying alive represents a moment of total extreme, both in terms of interpretation – how to imagine what passes through a person's mind in such agony – and representation – how to tackle the technical problem of showing both the exterior and interior results.

Titian was far from the first to tackle the problem. Beyond classical and renaissance representations of Marsyas, Christian iconography dealt regularly with Saint Bartholomew, who, according to the thirteenth-century text Golden Legend, suffered the double fate of inverted crucifixion and being flayed alive. Often, treatments of that scene were indirect.

Michelangelo's Last Judgement fresco in the Sistine Chapel depicts the saint, whole and resurrected, clutching the ghostly droop of his own skin.

More commonly, artists depicted Bartholomew unhurt, holding the knife with which he was peeled. As the National Gallery's recently acquired portrait by Bernardo Cavallino (1640–1645) shows, though, this too has a power of horror.

We are delighted to announce that we have acquired Bernardo Cavallino's 'Saint Bartholomew'.

— National Gallery (@NationalGallery) January 31, 2023

This is one of the largest and most splendid works Bernardino Cavallino ever painted and dates to the 1640s, when the Neapolitan artist was at the height of his artistic powers. pic.twitter.com/QiugAZaVCP

Cavallino's chiaroscuro focuses our gaze above all else on the saint's skin, sumptuously rendered, and the bolt of fabric draped across it. The inevitable thought is of the knife turning living skin into a kind of fabric too, and of the ultra-nakedness of the flesh beneath.

More brutal pictorial possibilities were explored too, of course. In a thirteenth-century French collection of saints' lives held in the British Library, the apostle's torture takes place within the confines of a single initial 'O'. Against a brilliant background of gold, he is held writhing on a bench as two skinners turn his chest into a scarlet splash of blood.

Depiction of Saint Bartholomew being flayed

13th C, illuminated manuscript made in France

Later artists brought all the advantages of expanded scales and new techniques to summon death to life in increasingly inventive ways. None more so than Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), for whom Bartholomew and Marsyas alike held a fascination, and whose images of both spare no detail of the pain involved. While those paintings show the suffering writ large, he was capable of reducing it in no less striking ways.

Apollo and Marsyas

1637, oil on canvas by Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652)

His 1624 print of Bartholomew draws on classical images of Marsyas tied to a tree, substituting the aged apostle for the satyr. It is movingly brutal. As the saint looks heavenward, one torturer, knife gripped between his teeth, pulls back a ragged flap of skin from his arm to reveal the muscles beneath; another, sharpening his own blade, leers directly at the viewer from the shadow of the tree.

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew

1624, engraving by Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652)

The image was popular enough that painted copies of it can be found in both the Royal Collection and the Wellcome Collection.

In an artistic tradition loaded with the brutality of the classical and biblical tales, violent deaths are hardly exceptional, but there is something elemental about flaying. Most wounds, placed here or there in the body, hold the possibility of escape from a pain defined in place – of mental separation from that part of the body.

Flaying offers no such hope – at least not without the kind of angelic intervention fondly imagined by religious artists in later centuries. To imagine the body being stripped of skin is to imagine not just being wounded but, as Ovid puts it, becoming a wound. Pain with no location and no boundary.

At the same time, the possibility of detaching from that horror offers the chance for a special kind of objectivity – both artistic and scientific. In the sixteenth century, as art interacted with the discourses of natural philosophy, getting under the skin became a vital enterprise for understanding how bodies really looked, and how they worked.

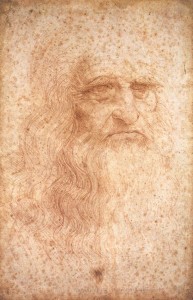

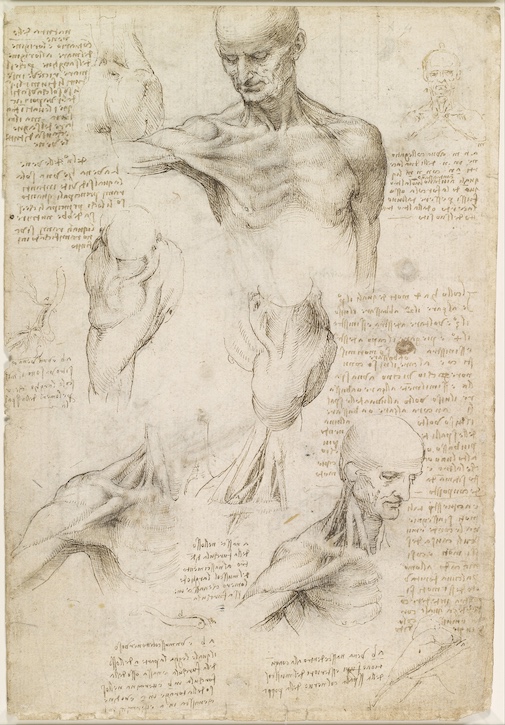

Leonardo da Vinci's (1452–1519) famous anatomical studies are symptoms of a confluence between art and science, which, on its journey into the workings of the human machine, started with flaying as its first step. The results were the exquisite muscle-men or écorchés that became almost ubiquitous in the period.

Superficial anatomy of the shoulder and neck (recto)

c.1510, pen & ink with wash, over traces of black chalk by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

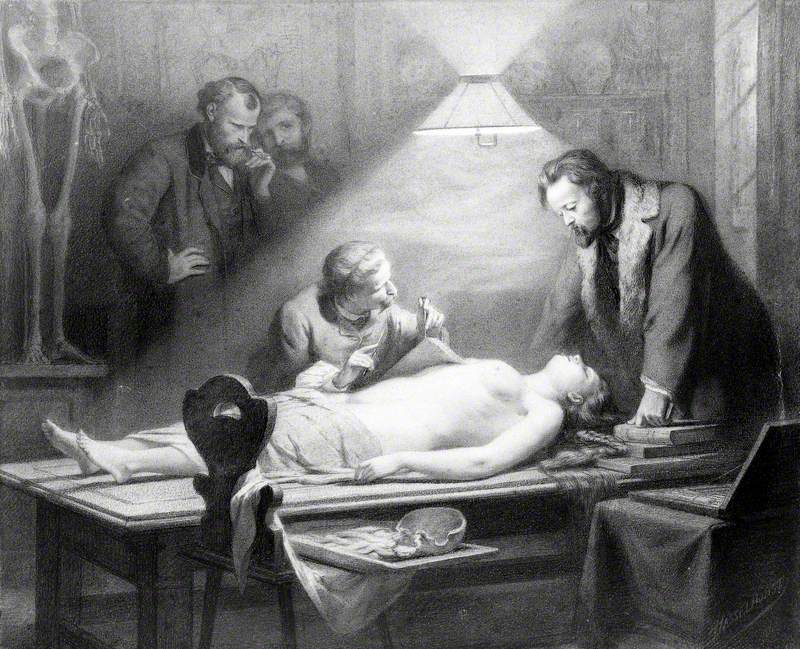

Beginning with Andreas Vesalius' De humani corporis fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body, 1543), which details Vesalius' own dissections, the new age of anatomical figure studies mark the beginnings of a revolutionary partnership. This was especially true in Britain with the appointment of the great surgeon William Hunter (1718–1783) as the Royal Academy of Arts’ inaugural Professor of Anatomy.

A painting by Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) shows Hunter in a lecture demonstrating anatomy to art students flanked by a live model and a life-size écorché.

By the eighteenth century, however, it was possible to go further than ever before: in 1771, Hunter cast an écorché directly from the flayed body of a murder, removed for anatomisation still warm from the scaffold.

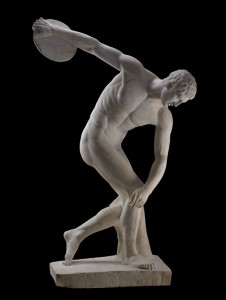

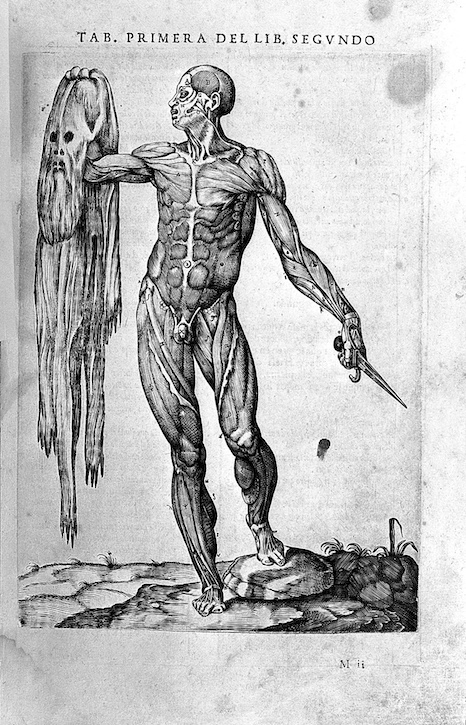

The irony of the écorché, though, is that its objectivity is as fantastical as anything in Ovid or the Golden Legend. In Titian, the wounds are barely visible, and yet Apollo's helpers need a bucket for the blood. In the new age of anatomy, the muscle men are bloodless and blithe. As they cross the pages of works such as Vesalius' Fabrica and its kin, they wander through classical landscapes with studied grace, to show off to the best advantage all the muscles in motion.

A flayed man holding his own skin

1556, printed illustration from Juan de Valverde de Amusco's 'Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano', attributed to Gaspar Becerra (c.1520–1570)

They are as far from the agony of death as could be: detached not just from their skin, but from all the pain proper to it. So much so, that in the most famous of Gaspar Becerra's illustrations to Juan de Valverde de Amusco's Historia de la composicion del cuerpo humano (History of the Composition of the Human Body, 1556), the first écorché walks onto the page having skinned himself for the viewer's edification – proudly holding both his own hide and the knife he used to strip it.

Unlike Titian's Marsyas or Ribera's Bartholomew, they might show how the body works but they cannot show how it feels.

Tim Smith-Laing, writer and critic based in London

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation