I have a new hobby – exploring Art UK. It is amazing what you can find there. You can peruse artists and sitters, subject matter and collections, navigating between them as you like. I usually look for works by specific artists, but you can have enormous fun searching under rather broader themes – such as ‘Dogs’, ‘Fire’ or ‘Interiors’ – which throw up all sorts of unusual and unlikely paintings in our national collections. Real discoveries can be made too.

I have just been searching the theme of ‘Death’, because I rather like pictures with a gloomy and morbid subject matter. Over 200 paintings were returned, from which you can call up larger images and find out more information. As expected, there are lots of pictures depicting the demise of the heroes and heroines of classical antiquity – Achilles, Dido, Cleopatra, etc. – and the beastly ends meted out to saints and Biblical wrongdoers.

Some sublime masterpieces stand out, Titian’s majestically fleeting The Death of Actaeon in The National Gallery is well-known, but who realised that a work attributed to Nicolas Régnier, the polished The Death of Sophonisba of 1665–1667 is held at Leicester Arts and Museums Service?

Image credit: Leicester Museums and Galleries

The Death of Sophonisba 1665–1667

Nicolas Régnier (c.1590–1667) (attributed to)

Leicester Museums and GalleriesThe same artist’s version of the death of Saint Sebastian is in Hull!

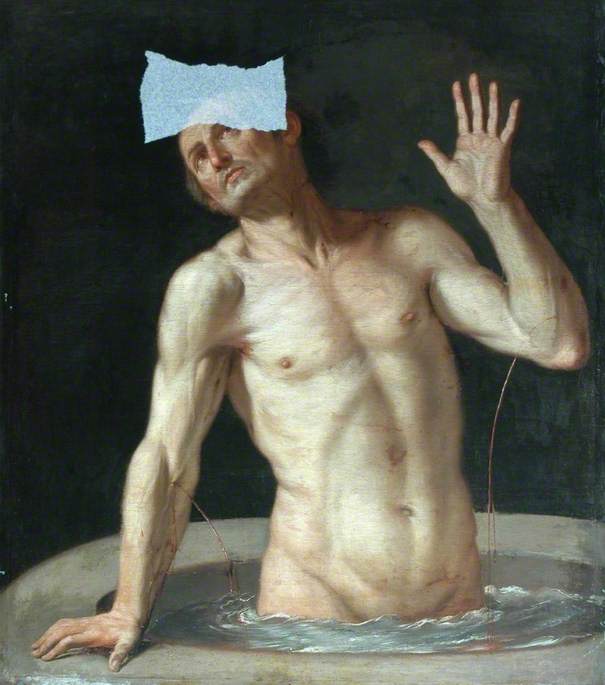

Surely The Bowes Museum’s gruesome The Death of Seneca, which shows an elderly man bleeding to death in a giant bath tub (based on a famous but much-restored Roman statue once at Villa Borghese), is earlier than c.1800?

The painting in the style of Egbert van Heemskerck the elder, Deathbed Scene with a Physician Examining a Urine Flask is, not surprisingly, in the collection of that fathomless reservoir of medical matters, the Wellcome Library.

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

A Deathbed Scene with a Physician Examining a Urine Flask

Egbert van Heemskerck II (1634/1635–1704) (style of)

Wellcome CollectionThey also have a rich collection of paintings of the Grim Reaper, from the little oil on copper Death and the Miser by Frans Francken II, to examples of those curious Life and Death pictures, which show one half of a fashionably dressed exquisite reduced to grinning bones.

This theme of ‘vanitas’, reaches its peak in Thomas Jones Barker’s The Bride of Death (1839) in the Victoria Art Gallery in Bath – a decomposing beauty perfectly encapsulating the morbid taste of our Victorian forefathers!

Compare this Grand Guignol fantasy with the Honourable John Collier’s The Death of Albine, another stricken bride of 1898, in Glasgow Museums.

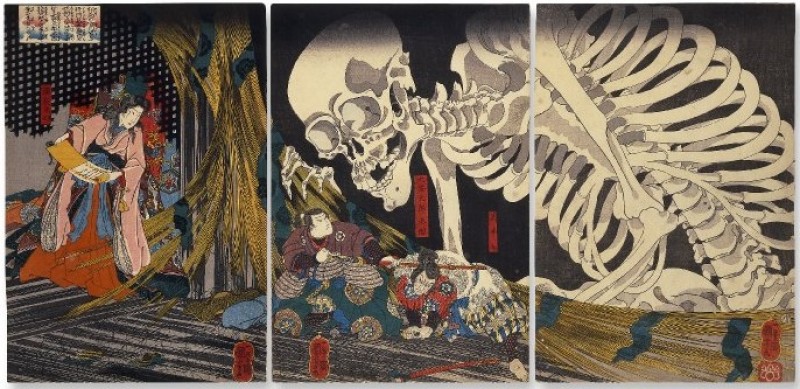

In Joseph Wright of Derby’s The Old Man and Death (c.1775) from the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, Death, in the form of an articulated skeleton, complete with arrow, apprehends a poor labourer as he works.

Then there are the historical deaths. As one might expect in British public collections, Horatio Nelson does particularly well, with many contradictory depictions of the Admiral’s heroic death on shipboard at Trafalgar.

The largest must be Daniel Maclise’s The Death of Nelson in Liverpool, a study for the even larger mural in the Palace of Westminster, which is so big that it cannot yet be photographed in its entirety. But I liked Edward Armitage’s 1848 The Death of Nelson – a sort of Regency secular pieta, with Nelson stripped down to his underclothes, from the Britannia Royal Naval College in Dartmouth.

Maclise’s monster panorama inspired John Minton’s The Death of Nelson (after Daniel Maclise) of 1952, a very fine early painting at the artist's alma mater, the Royal College of Art in London.

Other discoveries for me include James Northcote’s dramatic The Death of Prince Leopold of Brunswick (painted between 1785 and 1807, Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow), in which the shipwrecked, heavily bemedalled, Prince is seen being sucked into the briney deep.

Image credit: The Hunterian, University of Glasgow

The Death of Prince Leopold of Brunswick 1785 & 1807

James Northcote (1746–1831)

The Hunterian, University of GlasgowI can also tell the town fathers of Nuneaton that their huge, moulting, ‘British School’ The Death of Elizabeth I is in fact a copy after Paul Delaroche’s masterpiece in The Louvre.

Image credit: Nuneaton Museum and Art Gallery

The Death of Elizabeth I (copy after Paul Delaroche) mid-19th C

British School

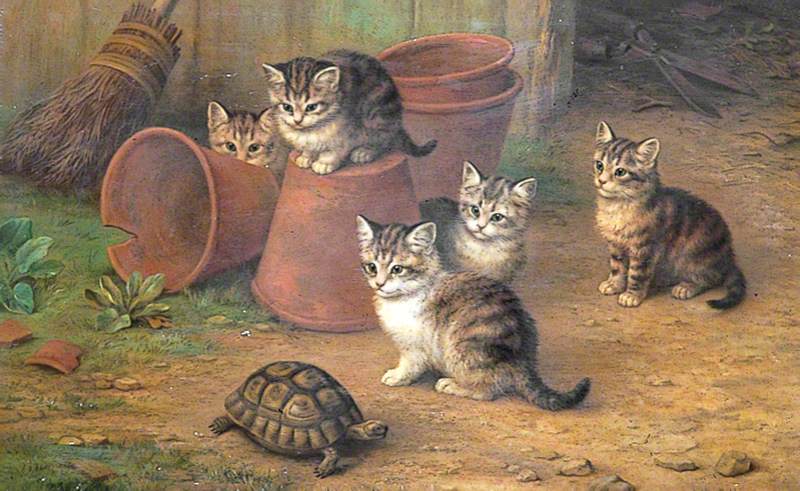

Nuneaton Museum and Art GallerySometimes the title of a picture is misleading, Edgar Hunt’s exciting-sounding Dicing with Death (1941) in Dover Museum, shows five sugary kittens balefully regarding a tortoise from the safety of some flower pots!

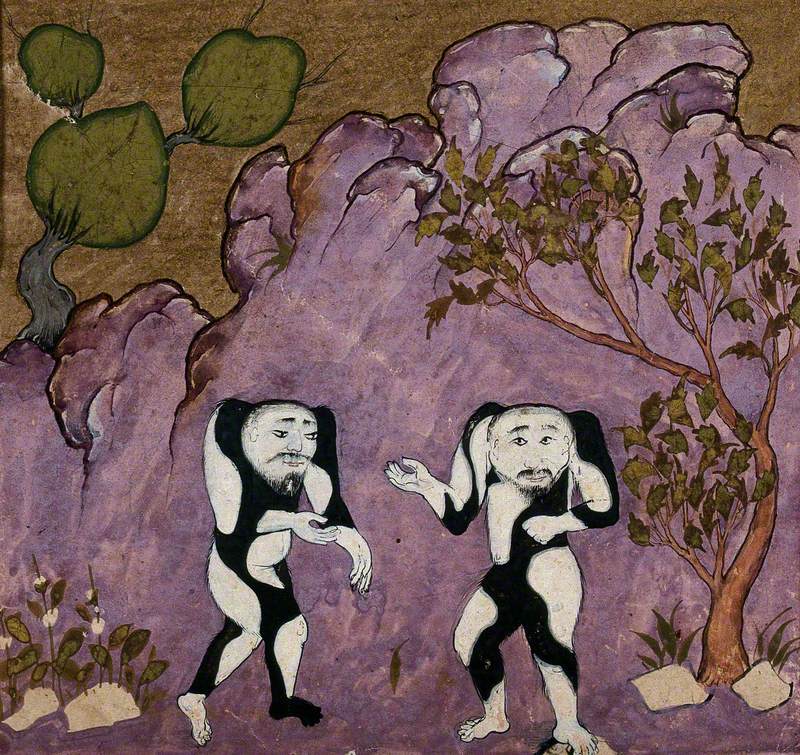

Meanwhile, Henry Fuseli’s lugubrious The Italian Count (1780) in my own Museum, Sir John Soane's Museum, depicts the aftermath of a particularly violent murder!

Image credit: Sir John Soane’s Museum

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)

Sir John Soane’s MuseumTim Knox, Director, Sir John Soane’s Museum