(b Málaga, 25 Oct. 1881; d Mougins, nr. Cannes, 8 Apr. 1973). Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, draughtsman, ceramicist, and designer, active mainly in France, the most famous, versatile, prolific, and influential artist of the 20th century. Although it is conventional to divide his work into certain phases, all such divisions are to some extent arbitrary, as his energy and imagination were such that he often worked simultaneously on a wealth of themes and in a variety of styles. He said: ‘The several manners I have used in my art must not be considered as an evolution, or as steps toward an unknown ideal of painting. When I have found something to express, I have done it without thinking of the past or future. I do not believe I have used radically different elements in the different manners I have used in painting.

Read more

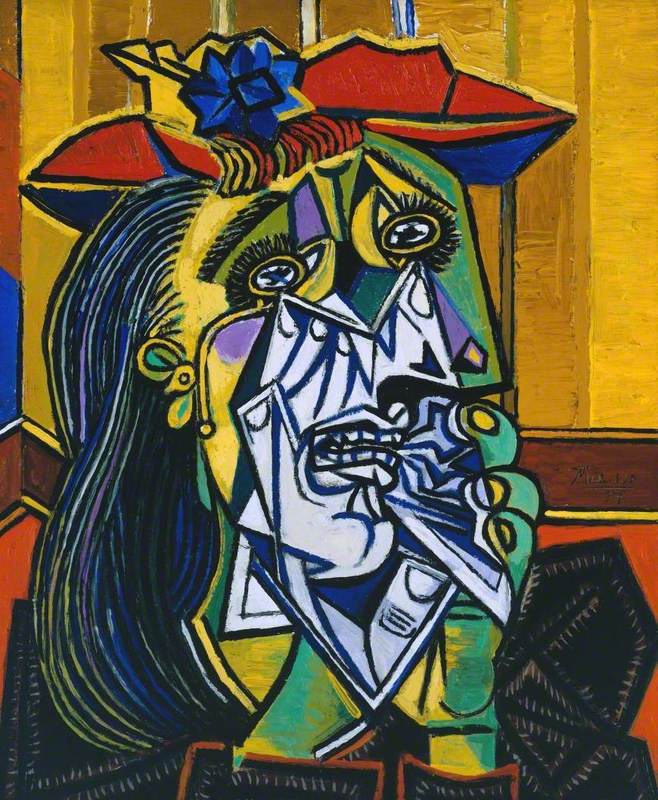

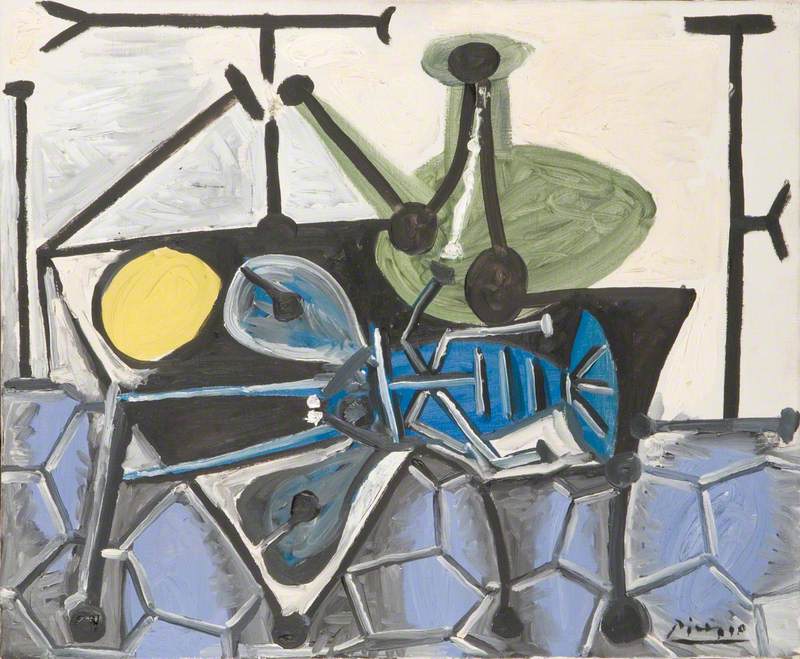

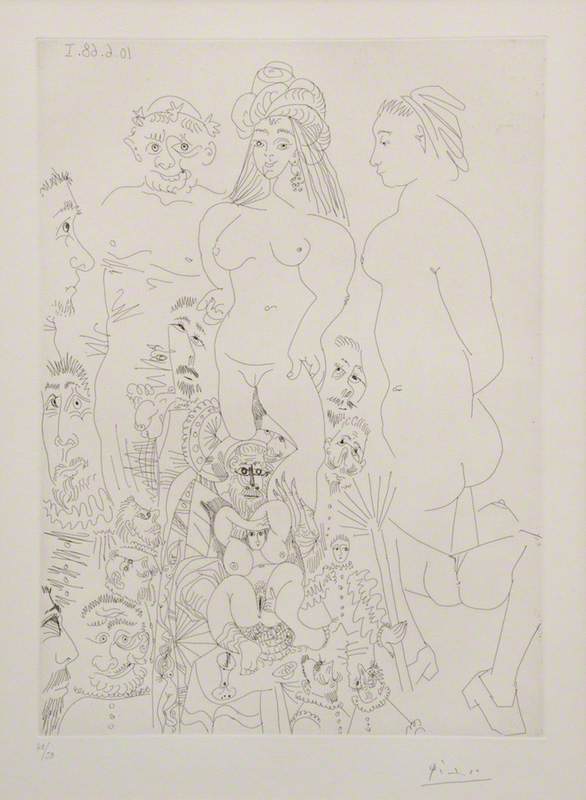

If the subjects I have wanted to express have suggested different ways of expression, I haven't hesitated to adopt them.’Picasso was the son of a painter and drawing master and was immersed in art from childhood (his first word is said to have been piz, baby talk for lápiz, ‘pencil’). In 1900 he made his first visit to Paris and by this time had already absorbed a wide range of influences. Between 1900 and 1904 he alternated between Paris and Barcelona, and these years coincide with his Blue Period, when he took his subjects from social outcasts and the poor, and the predominant mood of his paintings was one of slightly sentimental melancholy expressed through cold and ethereal blue tones (La Vie, 1903, Cleveland Mus. of Art). He also made a number of powerful etchings in a similar vein (The Frugal Repast, 1904). In 1904 he settled in Paris and quickly became part of a circle of avant-garde artists and writers. A brief phase in 1904–5 is known as his Rose Period. The predominant blue tones of his earlier work gave way to pinks and greys and the mood became less austere. His favourite subjects were acrobats and dancers, particularly the figure of the harlequin. In 1906 he met Matisse, but although he seems to have admired the work being done by the Fauves, he did not share their interest in the decorative and expressive use of colour (indeed his work often shows little concern with colour, and it is significant that—unlike most painters—he liked to work at night by artificial light). The period around 1906–7 is sometimes called Picasso's Negro Period, because of the impact that African sculpture made on his work, but Cézanne was an equally powerful influence at this time, when he was engrossed in the analysis of form. His explorations climaxed in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1906–7, MoMA, New York), which in its distortions of form and disregard of any conventional idea of beauty was as violent a revolt against tradition as the paintings of the Fauves in the realm of colour. At the time, the picture was incomprehensible even to other avant-garde artists, including Matisse and Derain, and it was not publicly exhibited until 1916 and only one reproduced before 1925. It is now seen not only as a pivotal work in Picasso's personal development but also as the most important single landmark in the development of 20th-century painting. It was the herald of Cubism, which he developed in close association with Braque and then Gris from 1907 up to the First World War.During the war Picasso continued working in Paris, but in 1917 he went to Rome with his friend Jean Cocteau to design costumes and scenery for the ballet Parade, which was being produced by Diaghilev. Picasso fell in love with one of the dancers, Olga Koklova, and married her in 1918; they moved into a grand apartment in a fashionable part of Paris, as the bohemian days of his youth were left behind. The visit to Italy was an important factor in introducing the strain of monumental classicism that was one of the features of his work in the early 1920s (Mother and Child, 1921, Art Inst. of Chicago), but at this time he was also involved with Surrealism—indeed André Breton hailed him as one of the initiators of the movement. However his predominant interest in the analysis and synthesis of form was at bottom opposed to the irrational elements of Surrealism, its exaltation of chance, or its fascination with material drawn from dreams or the unconscious. Following his serene classical paintings, Picasso entered on a period when his work was typified by violent emotions and expressionist distortion, the elements of the human face often being rearranged to convey intensity of feeling. This phase began with The Three Dancers (1925, Tate, London), a savage parody of classical ballet, painted at a time when his marriage was becoming a source of increasing unhappiness and frustration (he could not obtain a divorce, so he remained officially married to Olga until her death in 1955; he remarried in 1961). The period culminated in his most famous work, Guernica (1937, Centro Cultural Reina Sofía, Madrid), produced for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris Exposition Universelle of 1937 to express horror and revulsion at the destruction by bombing of the Basque capital Guernica during the civil war (1936–9). It was followed by a number of other paintings attacking the cruelty and destructiveness of war, including The Charnel House (1945, MoMA, New York): ‘Painting is not done to decorate apartments’, he said; ‘it is an instrument of war against brutality and darkness.’ Picasso remained in Paris during the German occupation, but from 1946 he lived mainly in the south of France, where he added pottery to his many other activities. His later output as a painter does not compare in momentousness with his pre-war work (indeed some critics think there was a sad decline in his powers), but it remained prodigious in terms of sheer quantity. It included a number of variations on paintings by other artists, including 44 on Las Meninas of Velázquez (the theme of the artist and his almost magical powers is one that exercised him greatly throughout his long career). In his old age he was haunted by the idea of death, and images of physical decay and the contrast between youth and age occur frequently in his work, as if he hoped to ward off his own end through the potency of his art. Some of his late paintings are aggressively sexual in subject and almost frenzied in brushwork (Reclining Nude with Necklace, 1968, Tate); they have been seen as sources for Neo-Expressionism.Picasso's status as a painter has perhaps overshadowed his work as a sculptor, but in this field too (although his interest was sporadic) he ranks as one of the outstanding figures in 20th-century art. He was one of the first artists to make sculpture that was assembled from varied materials rather than modelled or carved (in this way he helped to inspire Constructivism), and he made brilliantly witty use of found objects (see objet trouvé). The most celebrated example is Head of a Bull, Metamorphosis (1943, Mus. Picasso, Paris), made of the saddle and handlebars of a bicycle. Alan Bowness has written (Modern Sculpture, 1965), ‘Picasso's sculpture sparkles with bright ideas—enough to have kept many a lesser man occupied for the whole of a working lifetime…it is not inconceivable that the time will come when his activities as a sculptor in the second part of his life are regarded as of more consequence than his later paintings.’ As a graphic artist (draughtsman, etcher, lithographer, linocutter), too, Picasso ranks with the greatest of the century, showing a remarkable power to concentrate the impress of his genius in even the smallest and slightest of his works. His emotional range is as wide as his varied technical mastery: by turns tragic and playful, his work is suffused with a passionate love of life, and no artist has more devastatingly exposed the cruelty and folly of his fellow men or more rapturously celebrated the physical pleasures of love. There are several museums devoted to him in France and Spain, the largest being in Barcelona and Paris, and other examples of his huge output are in collections throughout the world. Just as this extraordinary oeuvre has been more discussed than the work of any other modern artist, so Picasso's personal life has inspired a flood of writing, particularly regarding his relationships with women. He once characterized them as either ‘goddesses or doormats’ and he has been criticized for allegedly demeaning them in his work (especially his later erotic paintings) as well as mistreating them in person.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)