The telling detail

A leading scholar of Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569), the art historian Joseph Leo Koerner, wrote that a work by the Flemish artist 'can sustain a lifetime of looking'. We think of the incredibly detailed and profusely peopled paintings usually associated with the artist. But there's a quite different work in the Courtauld Gallery, London, which also rewards a closer look.

Landscape with the Flight into Egypt

1563

Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Bruegel's Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (1563) – the title itself suggests that landscape is the presiding theme – is by Bruegel's standards a small painting, almost a miniature, luminous and exquisitely made. As we take it in, we quickly find a patch of red in the foreground: a woman on a donkey. Then a less conspicuous figure in grey, its back to us, leading the way down the hillside. This is the story of the biblical figure Joseph taking his family to safety in Egypt, to escape Herod's orders to kill all first-born male children.

Bruegel presents the Holy Family almost as incidental details against the immensity of nature. They are leaving behind low-lying, gentler terrain for forbidding peaks and caves. Hardly discernible are tiny figures in the lower left, crossing a frail bridge across a gorge, foretelling hazards to come.

If we keep looking, we notice a small statue – an idol – tumbling from a gabled box on a tree. This falling idol comes from an account of the Flight found in an apocryphal Gospel. According to that text, as the Holy Family entered a temple on their way to Egypt, 'all the images fell, and every idol, cast on its face, showed itself clearly to be nothing', and so the arrival of Christ meant the end of paganism.

But a falling idol had quite different associations in Bruegel's time, when there was considerable tension between the endemic Catholicism of the region (and of the ruling Spanish Hapsburgs) and the growing appeal of Protestantism. Across Catholic Europe, reformist mobs attacked churches, destroying statues and imagery, and even killing clergy. For these iconoclasts, Catholic artefacts were similar to pagan icons, and shrines like the one depicted here (which usually housed representations of Mary) were easy targets.

So a detail which we might have missed reveals itself to have a dual significance: a scriptural reference and a topical allusion to the religious upheavals of the day.

Colour, line and form

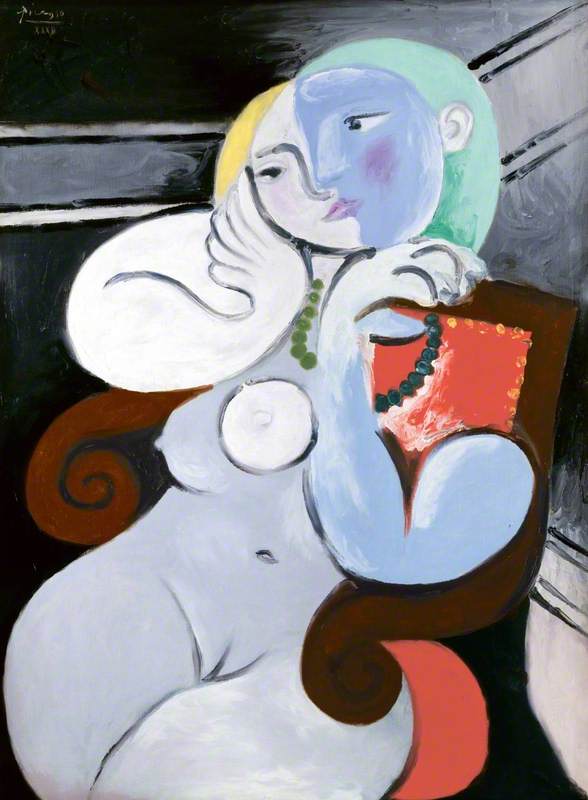

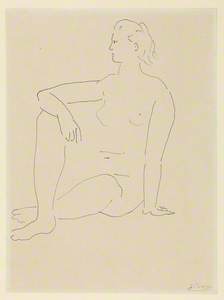

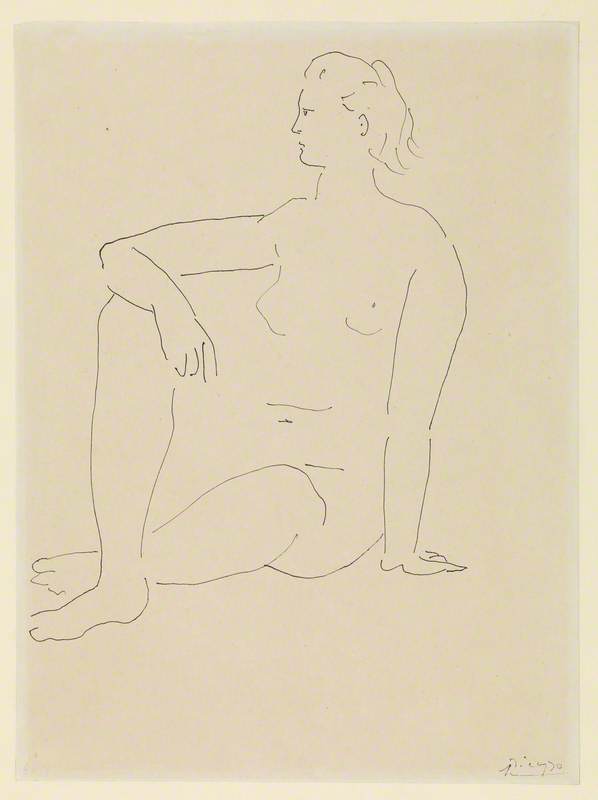

Spanish artist Pablo Picasso had extraordinary skill with line. He could evoke the body by the most delicate of means. In his Seated Woman (Femme assise) from around 1923–1925 – also in the Courtauld – even the absence of line is no deficiency.

Seated Woman (Femme assise)

c.1923–1925

Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

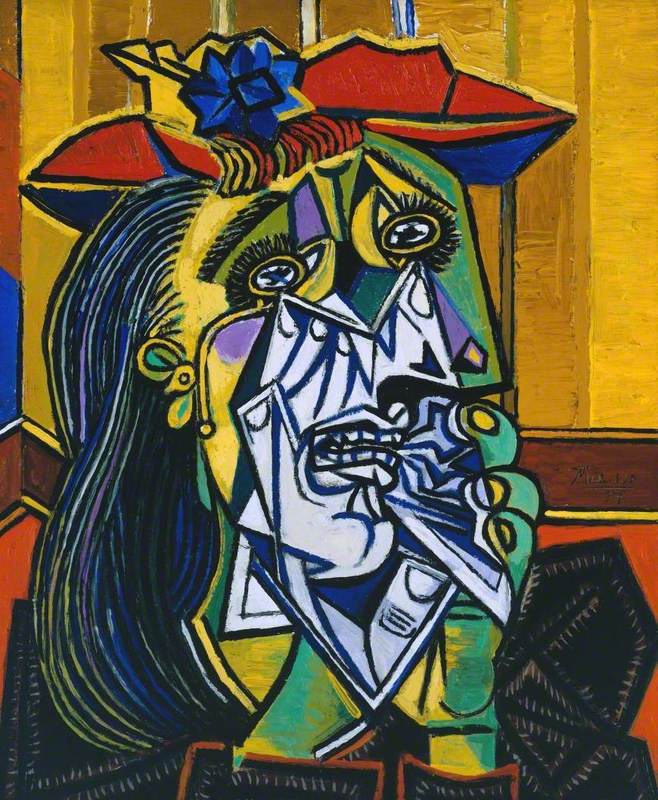

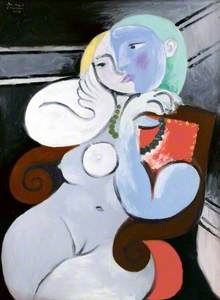

Picasso knew the power of line, form and colour as emotional triggers. In stark contrast to Seated Woman, his Weeping Woman (Femme en pleurs) (1937) in Tate Modern, London, achieves its effects in a barrage of expressive ways.

Weeping Woman is the culmination of a series of drawings and etchings of distraught women made in 1937, a year of civil war in Spain – the year of the terrorist bombing of the Basque town of Guernica. Picasso's monumental mural Guernica is itself fraught with gaping mouths, splayed limbs and panicked eyes. These forms affect us with the speed of a nervous impulse.

The sheer distress of Weeping Woman brings to mind the agonised faces of Christ and Mary in the throes of their sorrows, but Picasso's elaborate distortions aim for an even greater emotional impact.

Weeping Woman is a clenched concentration of anguish.

The red hat with its blue flower seems out of place amidst this tumult of emotion, incongruously, even comically (it might evoke Salvador Dalí's Lobster Telephone, made just a year earlier), reminding us of the reserve and normality of this woman before she was seized with sorrow. It is an image which combines the composed (hat, hair and earring) and the discomposed.

The red of the hat bleeds into the woman's fringe, but the predominant flow here is of tears. They course in lines like further fingers down the handkerchief, a handkerchief which appears to be in two places at once – gripped in one hand and between the teeth, and spiking at the eyes as it tries in vain to soak up the flood of tears. A single tear follows a bending track down the cheekbone, tipped from the boat of the woman's right eye. These small boats – upset in both senses – pour their tears down her face.

The lower part of the face is painted a skeletal bluey-white, as though it were an X-ray focusing on an exposing inner turmoil, while the rest of the skin is a sickly green and yellow, the colours of nausea.

When we look into those eyes, what do we see? Not the small spots of pupils but strange cross-like forms – the planes that bombed Guernica, according to artist Roland Penrose (1900–1984), who owned the painting before it was bought by the Tate: '...the reflection of the man-made vulture which has changed her delight into insufferable pain.'

But who is Weeping Woman? Picasso said it was Dora Maar (1907–1997), one in a series of lovers and muses of the great artist-egoist, the great consumer of muses. But Maar did not want to be identified with these tortured representations, saying 'They're all Picassos, not one is Dora Maar'.

It could be said that Maar's misfortune was bad timing – she became Picasso's model in the savage war years of the late 1930s, while Marie-Thérèse Walter (1909–1997) (whom Maar ultimately usurped) was painted repeatedly as a ravishing nude in more peaceful times.

Picasso kept both relationships alive, enjoying their jealousies. Although Maar played down the hurt she must have felt, Walter recalled life with Picasso as 'full of happiness, then of tears. Of tears above all... He was a wonderfully terrible man'.

Light and reflection

Two paintings in The National Gallery, London, contain details which surprise the eye by playing with the laws of physics.

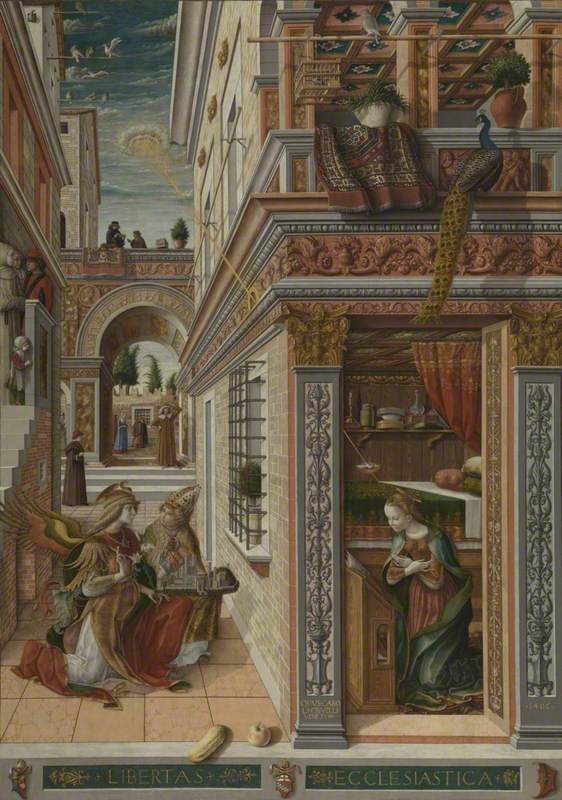

Italian Renaissance painter Carlo Crivelli's Annunciation with Saint Emidius from 1491 is a tour de force of perspectival representation. Its assertion of spatial depth is offset by the playfully outsized cucumber and apple in the foreground. Another detail, the shaft of light which zaps Mary from the distant sky, also flouts the reality it otherwise strives to represent.

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius

1486

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

A shaft of light is a common representation of the Holy Spirit in conferring on Mary the divine conception. Crivelli locates the source of this light in the line of the vanishing point where all things are directed (or from where all things come), yet allows his beam to take an impossible course through a tiny aperture in the wall where it strikes Mary in her private chamber: the supernatural disobeys earthly laws in seeking out the unsuspecting virgin.

In many Annunciation scenes there's a sense of encroachment into Mary's personal space, the space itself a metaphor for her virginity, but few are as fortified as these ornate walls, which nonetheless will not hide Mary from the penetrative force of God's will.

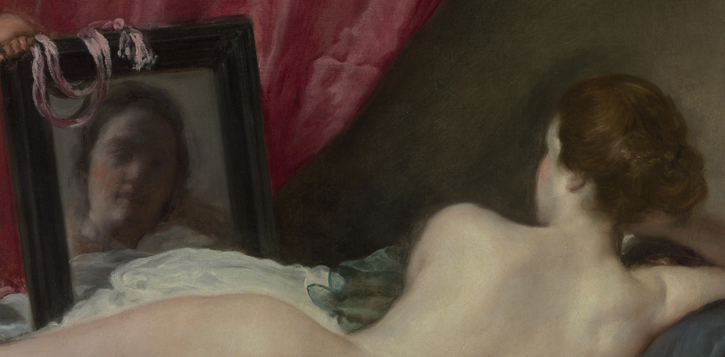

Another detail which defies expectation is the reflected face of the Venus in Diego Velázquez's Rokeby Venus (1647–1651). We may quickly realise that Venus cannot be admiring herself and looking at us at the same time. Velázquez has deliberately arranged things so that what appears at first to be an image of narcissism has instead a jolting sense of detachment and mutual surveillance.

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus')

1647-51

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

That long body spans the canvas like a landscape – a rolling ridge of hills, a horizon – that the indistinct face in the mirror appears not to belong to. 'Her body unfolds... into a moment of bodily sovereignty... turned elsewhere, opening out beyond', as critic Edward Snow describes it. This is not a sensuous nude but a majestic anatomy that Venus – as the face in the mirror – seems separate from.

It is commonly remarked that her face is indistinct in order to obscure its identity and allow us to project what we want to see there. But this may be Venus as she sees herself: less than ideal, with all her perceived flaws – that round, rosy-cheeked face, older and plainer, perhaps, than we expected from our rear view of that elegant head and neck.

A further discrepancy, which might escape us, is that Venus's head is too large in the mirror. From our viewpoint, her reflected image should appear twice as far away and therefore much smaller.

What do these distortions add up to? Is the mirror to be considered a painting within a painting, a portrait of Venus's inner self, held up by Cupid for all to see? Is it more vanitas (a reminder of the brevity and fragility of life) than vanity?

Whatever his reasons, Velázquez wanted us to see that framed face as separate from that exemplary body, lying like a sculpture across its languorous divan.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Judi Freeman, Picasso and the Weeping Women, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1994

James Lord, Picasso and Dora, Farrar Straus Giroux, 1993

George Mather, The Psychology of Visual Art: Eye, Brain and Art, Cambridge University Press, 2014

Stephanie Porras, 'Rural Memory, Pagan Idolatry: Pieter Bruegel's Peasant Shrines' in Art History 34, no. 3, 2011

Stephanie Porras, Pieter Bruegel's Historical Imagination, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016

Edward Snow, 'Theorizing the Male Gaze: Some Problems' in Representations, no. 25, 1989