Back in 2017, the first episode of BBC One's The Big Painting Challenge was all about still life.

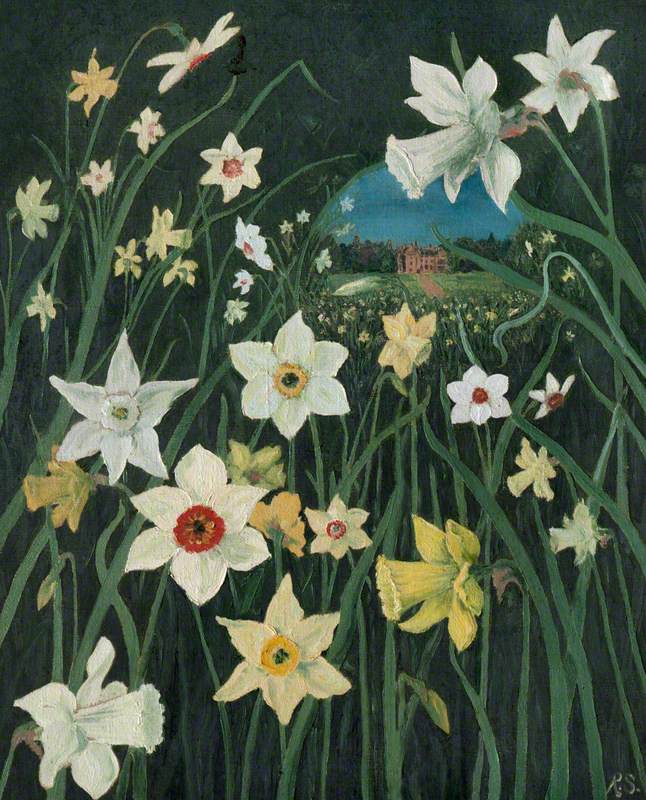

Chances are, 'still life' isn't a phrase that's going to set your pulse racing. More likely, it'll conjure up images of carefully arranged fruit, sprigs of plants or vases of flowers. Perhaps it brings to mind dark, musty, traditional compositions that your eye passes over in a gallery, quickly moving on to more colourful and lively things.

Historically, still life occupied the bottom rung of the 'hierarchy of genres' in the visual arts. In the seventeenth century, the French Royal Academy decided that 'man was the measure of all things', and so landscape and still life were the 'lowest' form of painting for not involving human subject matter. Still life, according to them, was simple: anyone could paint a peach, but it supposedly took a higher mastery of the craft to depict a Greek legend or a Biblical story.

Luckily, things have moved on since the seventeenth century and we can now look back and see if still life has just been given a bad historical rap. After all, as a genre it can encompass literally anything that isn't moving – there has to be some scope for making it exciting... right?

Can still life tell us anything interesting?

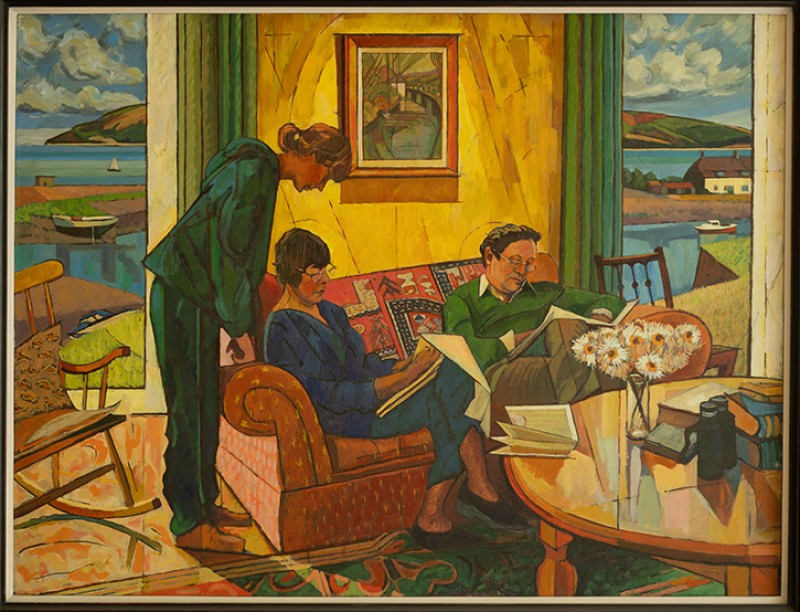

For starters, still life can be a portal to a personal kind of history. In some ways it's very intimate: the objects depicted by the artist reveal what they consider to be either of social or cultural importance, or of personal value to them.

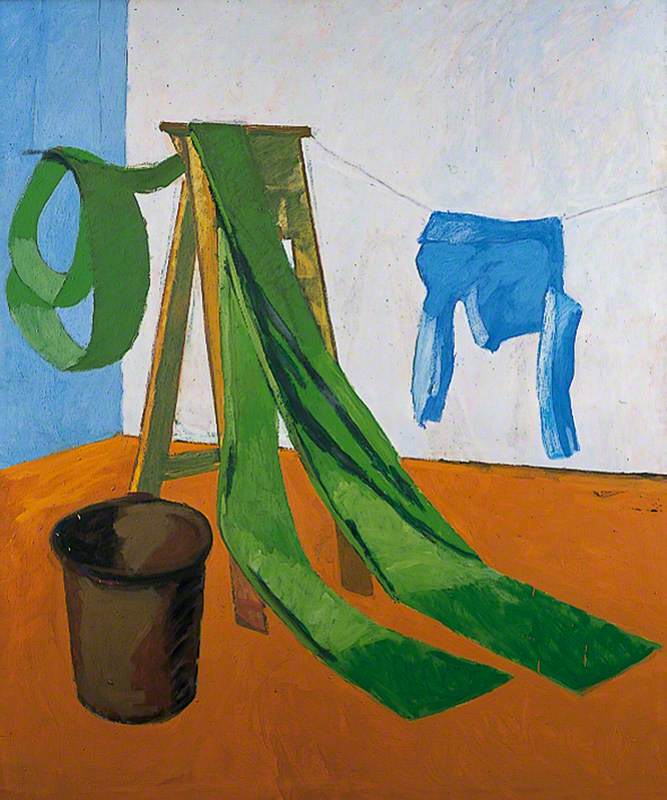

Look at the social realist movement, which used art to draw attention to the living conditions of everyday people. This still life by John Bratby tells us something about the realities of post-war Britain: instead of creating a traditional still life full of natural produce, Bratby painted the items found around him, representative of a typical household, in what would come to be known as a the 'kitchen sink' style.

On a different, but equally interesting, note, watermelons used to look really different – and still life paintings prove it, as told by our friends at Hyperallergic.

When did still life really get moving?

Still life has been around for a long time, as shown by paintings found on cave walls and from pre-volcanic Pompeii. Zeuxis, a Greek painter who was working in the fifth century BC, supposedly painted some grapes that were so realistic birds came down and tried to peck at them. None of Zeuxis' works have survived (possibly all eaten by birds?), but there are some extant examples of ancient 'still life', like this Roman painting of fruit.

However, we will fast forward to a time when still life really came into its own: the Dutch golden age. An increasingly wealthy middle class were keen to acquire and show off art, but historical and religious paintings proved unpopular.

Image credit: Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

Still Life of a Lobster, Vegetables, Fruit, and Game 1645

Adriaen van Utrecht (1599–1652)

Ashmolean Museum, OxfordStill life was straightforward and affordable for artists to produce: they didn't have to persuade or pay anyone to sit for them, just draw inspiration from arranging the everyday objects around them.

So exploded the Dutch tradition of still life painting, with artists including Pieter Claesz., Adriaen van Utrecht, Ambrosius Bosschaert (elder and younger), Willem Kalf and Rachel Ruysch, to name but a few.

However, it wasn't just about commercial gain. Still life gave an artist the opportunity to show off their technical skills, and to play with light and composition. Still lifes could also have symbolic meaning depending on the items depicted – which moves us on to...

Can still life remind us of our own mortality?

Yes it can, imaginary interlocutor.

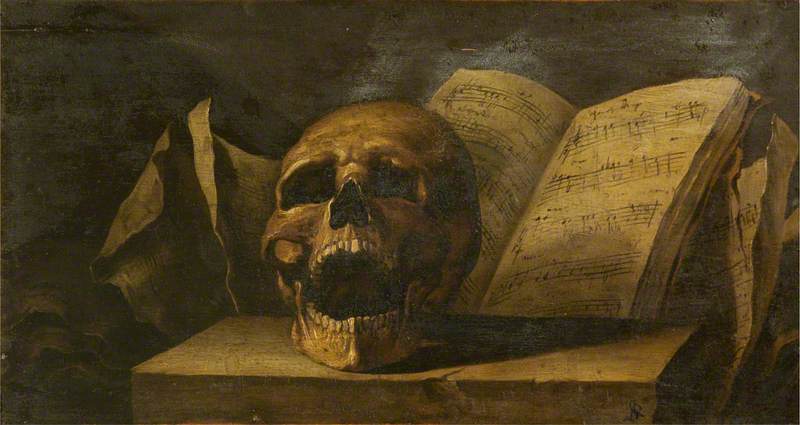

For art that's all about painting objects, still life has traditionally done a lot to remind us that material things aren't that important in our short lives. A lot of still life falls into the category of 'memento mori': art that's intended to remind the viewer of the brevity and fragility of human life. The phrase itself means 'remember you must die'.

Related to this, a 'vanitas' artwork tells us of the fruitlessness of accumulating material goods. A memento mori piece may contain deathly symbolism such as extinguished candles, ashtrays, watches, fruit (because it decays) or – less subtly – skulls.

A vanitas piece might include bottles of wine, musical instruments or books: things we enjoy on earth but can't take with us to the afterlife.

But is it all just Dutch old masters?

Let's fast forward again. In the eighteenth century we have Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin, widely considered an all-time master of the still life.

Rather than making use of traditional symbolism, Chardin simply aimed to represent the composition of items found in his own home. The Goncourt brothers put it best: '...never, perhaps, has the material fascination of painting dealing with objects of no intrinsic interest and transfiguring them by the magic of handling been developed so far... Who has expressed, as he has expressed, the life of inanimate objects?'

Chardin's pieces are, perhaps, the epitome of still life: simple items that have no symbolic meaning, simply arranged to achieve a kind of balance and unity, represented beautifully.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Still Life: The Kitchen Table c.1755–1756

Jean-Baptiste Siméon Chardin (1699–1779)

National Galleries of ScotlandThen we have Cézanne, whose still lifes are seen as a bridge between the styles of the old masters and the later Cubists. Cézanne's still lifes are notable for incorporating several different perspectives: almost like creating a sculpture. They bring in light, and strange composition, with fruit sometimes scattered almost haphazardly across the painting.

At this time, of course, we shouldn't forget Van Gogh, whose still lifes are so vibrant they draw in even the most casual of art fans.

Nice fruit and flowers. But can still life move forward?

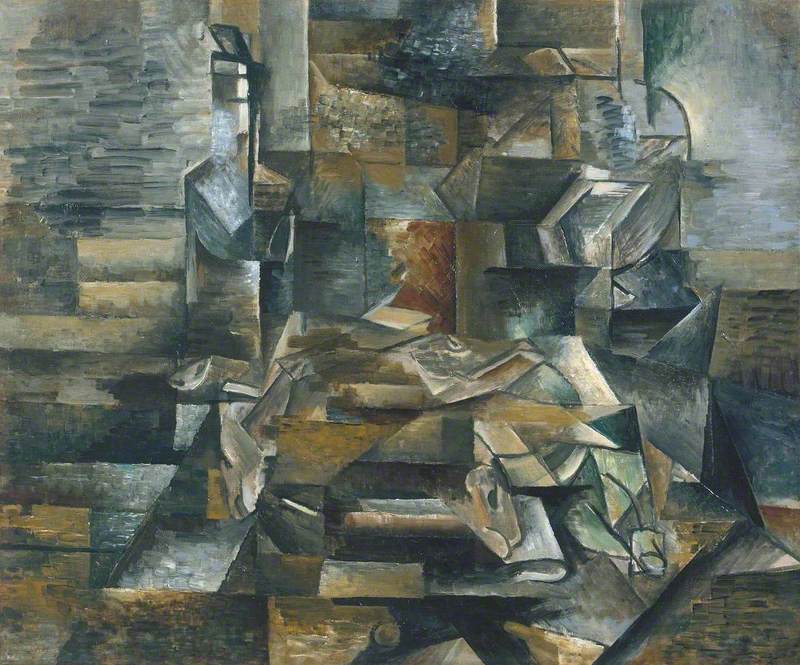

Yes. If we zip forward again, we get to twentieth century Cubism. Georges Braque, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso began using shapes and blocky forms to make still lifes that looked radically different to those of their predecessors.

The advent of photography freed artists from the obligation to paint items to be totally true to life: they could experiment with mood, colour, shapes and feeling rather than the pure technique of capturing the correct sheen on an orange.

Rather than symbolism of individual objects, the Cubists could play with the differences between appearance and reality.

Can still life be fun?

This moves us on nicely to Pop Art. Pop artists sought – as some of their still life predecessors had – to express everyday life: the people, the media, and of course, the objects. But they found a new style to do it in and new objects to depict: the typewriter, the soup cans, the lipstick. In America, pop still lifes were a way of getting back to painting real objects after the dominance of abstract expressionism, and for the first time, mass media and pop culture became the subjects of art.

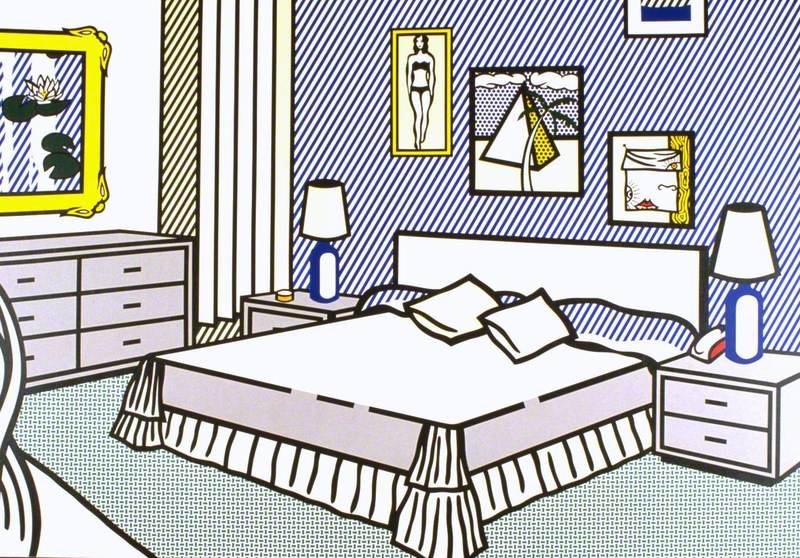

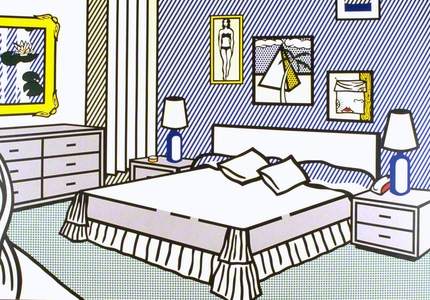

Roy Lichtenstein certainly had fun with his still lifes, aping the styles used by mass media and marketing and using them to depict otherwise mundane objects or situations.

He painted his still lifes in flat, outlined shapes inspired by newspaper and print advertisements and painted to look like the original. He made an imitation of Van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles, calling it Bedroom at Arles, and joking that had Van Gogh been alive the painting would have been to his liking.

Lichtenstein said of his work: 'When we think of still lifes, we think of paintings that have a certain atmosphere or ambience. My still life paintings have none of those qualities, they just have pictures of certain things that are in a still life, like lemons and grapefruits and so forth. It's not meant to have the usual still life meaning.'

Can still life be political or experimental?

Yes: the Guardian has an excellent list of contemporary still life artists, many of whom use photography to create their compositions, and whose work has political intent. Sharon Core, at the top of the list, pays homage to the Dutch greats by recreating their compositions as closely as possible.

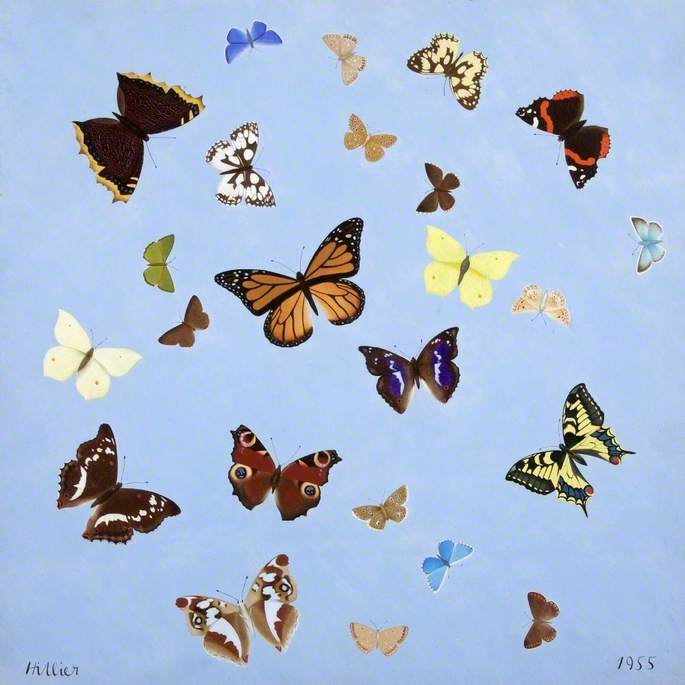

Mat Collishaw, another entry on the list, demonstrated this through his powerful photo series illuminating the last meals of prisoners on death row in the USA. His work in UK collections includes this trio of butterflies and flowers.

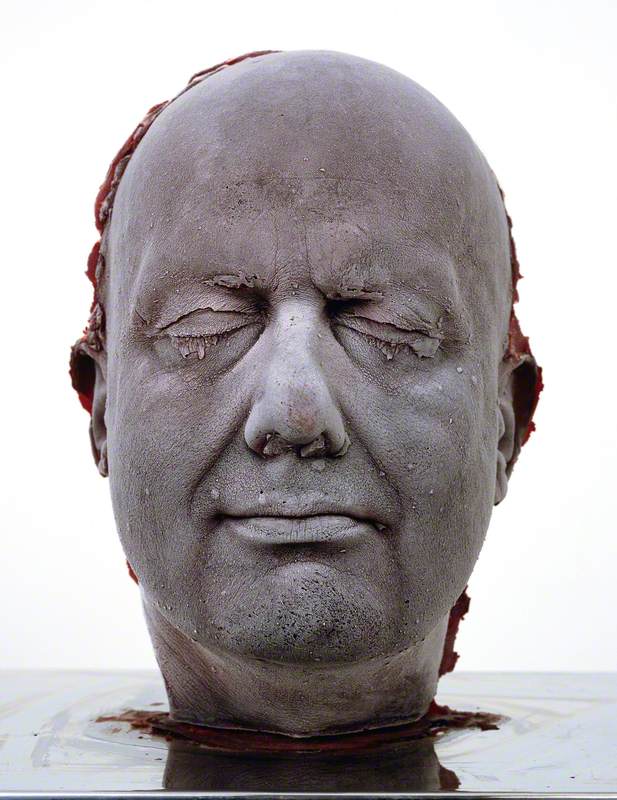

The list also includes Marc Quinn's Self, which they categorise as a still life sculpture.

The preoccupation with death perhaps puts it more in the 'vanitas' or 'memento mori' category...

Can anyone paint a still life?

It depends who you ask.

The furore around the art of the Young British Artists in the 1990s was often 'anyone could do it'. Anyone could get out of bed and call it 'art'. Anyone could daub some coloured spots on a canvas.

In 2012, Damien Hirst took a break from cutting up cows and pickling sharks to put brush to canvas. His venture into painting received mixed reviews: critics of his exhibition at the Wallace Collection voiced their disappointment and distaste for his works.

A particularly scathing Jonathan Jones wrote in the Guardian: 'If Hirst did not try to paint an orange accurately, no one would know he can't do it. But he has tried, at least I think it's an orange, and the poor sphere seems to float in mid air because of the clumsy circle of shadow below it.'

So... is there still life in still life?

Yes.

Still life has been frequently dismissed and derided – but also adopted and adapted by master painters. It's been sneered at for hundreds of years but continues to intrigue contemporary artists. Still life can encompass the mundane and the weird in equal measure, and it has never really gone away, merely waxed and waned – so who knows where an artist might take it next?

© Lucian Freud Archive / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Bridgeman Images

Still Life with Squid and Sea Urchin 1949

Lucian Freud (1922–2011)

Harris Museum, Art Gallery & LibraryNow please excuse me, I have some oranges to arrange in an artful fashion.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer