'The Director of the National Gallery has given the British public an electric shock. People gather in crowds in front of it, they argue and discuss and lose their tempers… Even if it should not be the superb masterpiece which most of us think it is, any sum would have been well spent on a picture capable of provoking such fierce interest in the crowd.'

These are the words of the critic, painter and champion of modern art Roger Fry, writing in 1919 about an exciting new acquisition by The National Gallery in London. But Fry is not talking about some avant-garde masterpiece by Paul Cézanne, Paul Gauguin or Henri Matisse. Rather he is praising a painting made more than 400 years earlier by the Greek artist Doménikos Theotokópoulos, more commonly known as 'El Greco' (1541–1614).

The Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane

1590s

El Greco (1541–1614) (studio of)

As Fry reported, The Agony in the Garden (1590s) caused public outcry when it was first displayed. The acrid colours, elongated figures and swirling semi-abstract landscapes led many to call the artist a madman, and the acquisition a colossal waste of public money (it cost £5,200). These debates about El Greco are not new. Even in his day, he was considered an eccentric, controversial and capricious painter. So, who is this 'Marmite' artist? And do you love him or hate him?

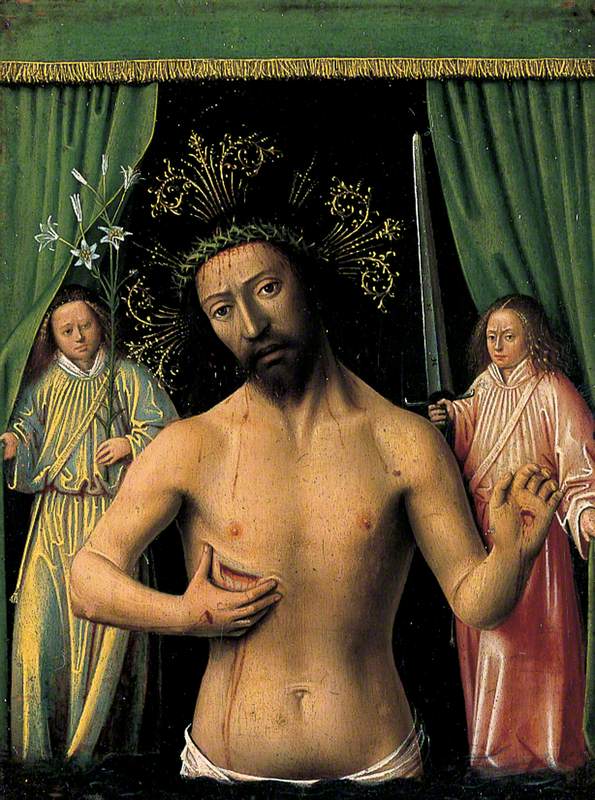

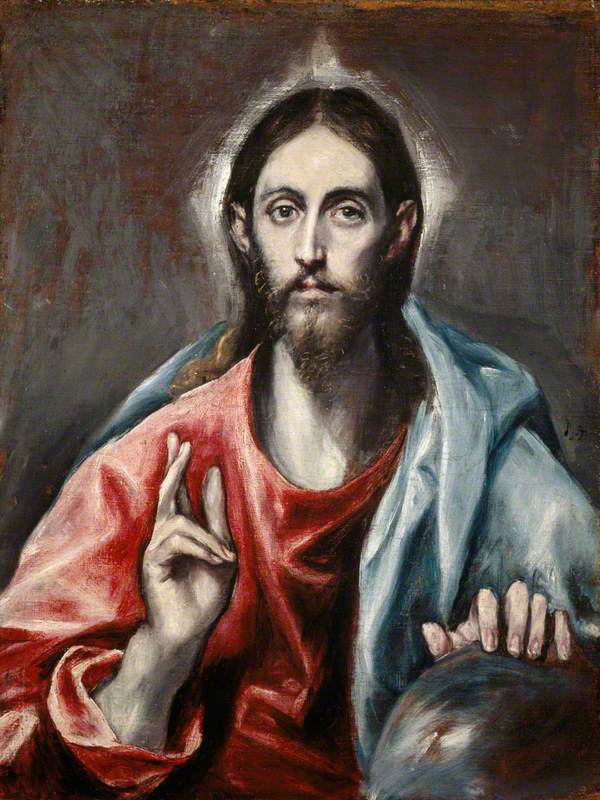

El Greco was born in Candia on the island of Crete in 1541. He first trained as an icon painter in the post-Byzantine manner, producing small religious panels with gold grounds and stiff, stylised figures. El Greco returned to these iconic forms throughout his life, even as his style developed and changed. In the National Gallery of Scotland's Christ Blessing, painted 30 years after he left Crete, we can still see these echoes of the Byzantine tradition of his youth.

Christ Blessing, The Saviour of the World

c.1600

El Greco (1541–1614)

In the spring of 1567, aged 26, El Greco set sail for Venice. The shining city on the lagoon was a marvel unlike anything he had seen and it, along with its art, had a profound effect on the young artist. At the time of El Greco's arrival in the city, the undisputed master of painting was the elderly Titian (c.1488–1576). For El Greco, Titian embodied the immortal ingenious painter, the artist courted by princes and for whom poems were written. In other words, he embodied everything El Greco aspired to become.

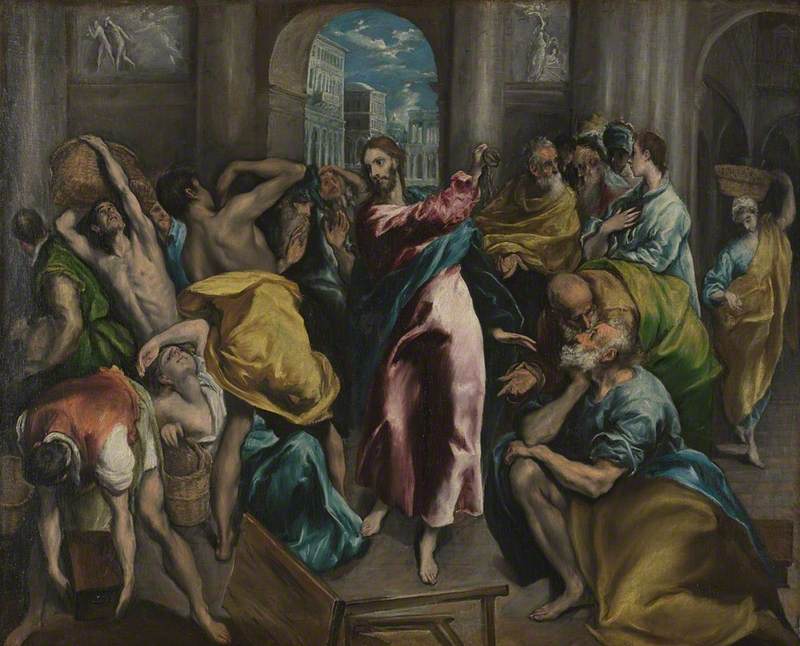

His admiration for Titian can be seen almost immediately in the paintings he produced. Christ Driving the Traders from the Temple (c.1600) was a composition that he first developed while in Venice and returned to many times throughout his career.

Christ driving the Traders from the Temple

about 1600

El Greco (1541–1614)

Gone are the gold backgrounds and stiff figures of his icon paintings. Instead, the bodies twist and writhe, and the space is rendered with depth and perspective. Looking through the arch, we see a gleaming marble-clad city with flat facades and colonnades. Here El Greco has transformed Jerusalem into Jacopo Sansovino's Venice.

In 1570, El Greco moved again, this time to Rome. Here he entered the circle of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, grandson of Pope Paul III and one of the greatest collectors of the age. The Palazzo Farnese where El Greco first lodged was full of interesting characters. Most notable was the painter and illustrator Giulio Clovio (1498–1578), nicknamed the 'Michelangelo of Miniatures'. Clovio and El Greco bonded over their shared eastern roots (Clovio was born in modern-day Croatia) and their interest in the arts of ancient Rome.

It may have been following discussions between the two men that El Greco painted An Allegory (Fàbula) (c.1580–1585). This strange subject, a boy blowing on an ember with a monkey and a man beside him, links to a painting described by the ancient Roman author Pliny the Elder. Pliny recounts a work so brilliant because it captured in paint the light from an ember flickering across a boy's face. In recreating this lost painting the young El Greco was laying claim to the laurels of the ancients.

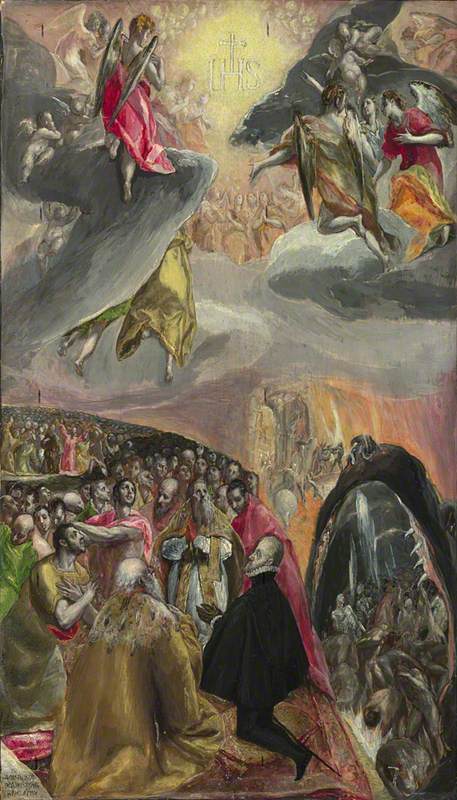

In 1577, El Greco was called to Spain to help decorate the colossal new palace-monastery of El Escorial in the mountains to the north-west of Madrid. Here he designed The Adoration of the Name of Jesus, a large altarpiece celebrating the victory of the 'Holy League' against the Turks at the Battle of Lepanto. The Holy League was a collaboration between the Pope, the Doge of Venice and Philip II of Spain, and El Greco includes their portraits in the lower left of the painting. The National Gallery's small sketch of the altarpiece is likely a version made by El Greco to record the painting.

To the right is the gaping maw of the Hellmouth swallowing the damned. The writhing, drowning souls, painted with violent flicks of the brush, show El Greco at his most expressive and disturbing. Perhaps it was this unorthodox style that turned Philip II against the artist, or maybe it was El Greco's grating, arrogant character. Either way, the artist never worked for the king again. Instead, he settled in Toledo, the centre of the Catholic Church in Spain.

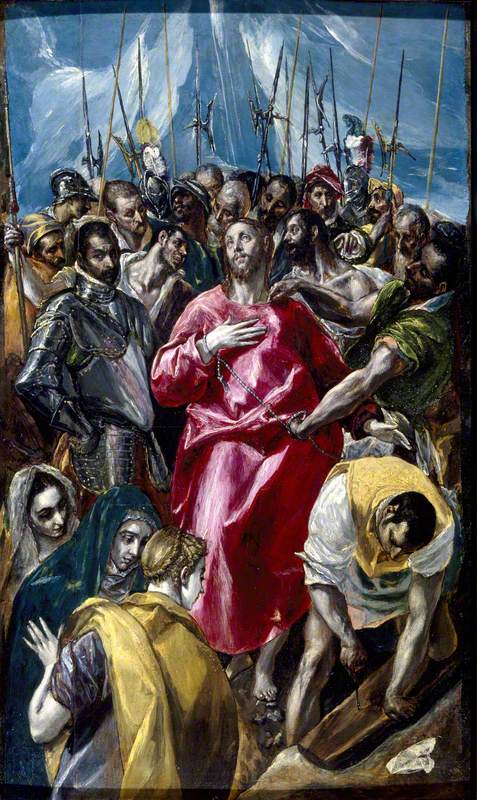

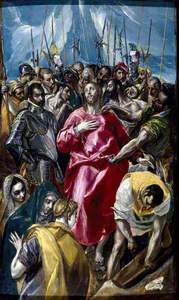

These years in Toledo were not without their own controversies. One of the first surrounds his painting of The Disrobing of Christ (1577–1579; the larger work from which the Upton House sketch below derives currently hangs in the Sacristry of Toledo Cathedral). It was designed for the altar in the vestiary of Toledo Cathedral, the room where the priests put on their religious robes or vestments, before a service. Christ, drenched in a blood-red robe, is surrounded by a baying mob. The space is flattened and distorted so that the crowd seem to press continually in, jostling, leering and grabbing at Christ – a claustrophobe's nightmare.

The cathedral hated the painting and refused to pay. Most egregious, they argued, was the inclusion of the three Maries (Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalen and Mary Salome) in the bottom left corner as these figures aren't present in the Bible's narrative, and the fact that Christ's head is below figures in the crowd was regarded as a near-heretical slight. This was the first legal dispute El Greco had to settle in Spain, but it would not be his last.

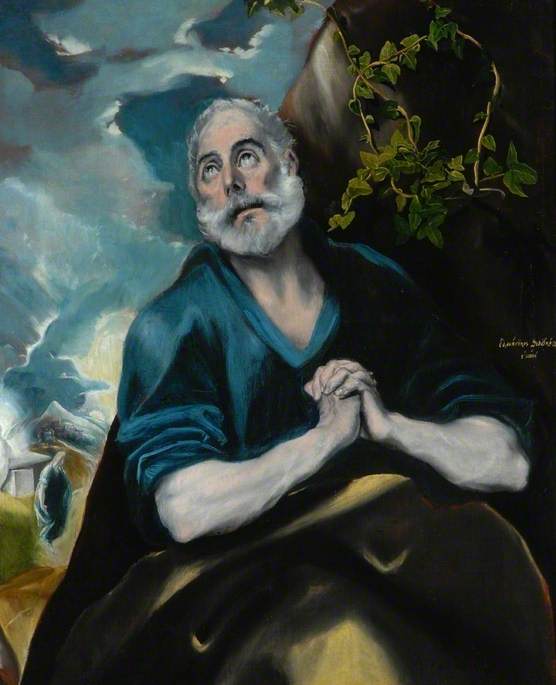

Despite these controversies, El Greco became immensely successful in Toledo. Most popular were his images of saints, filled with a religious fervour that stirs us even today. In Britain, we have four great examples, one from the beginning and the other three from nearer the end of the artist's career in Toledo. The Tears of Saint Peter (c.1580–1589) at the Bowes Museum in County Durham was painted a few years after the artist settled in the city. It depicts Saint Peter desperately praying for forgiveness after he has denied Christ during the Passion story.

It is one of the best El Grecos in the country and illustrates the full spectrum of his virtuosic style. Compare for a moment the detail and delicacy of the ivy catching the light on the right to the landscape of near-abstract volumes and forms on the left. Note also the prominent golden signature in curling Greek letters – despite his many years abroad, Doménikos never lost his pride in his Cretan heritage.

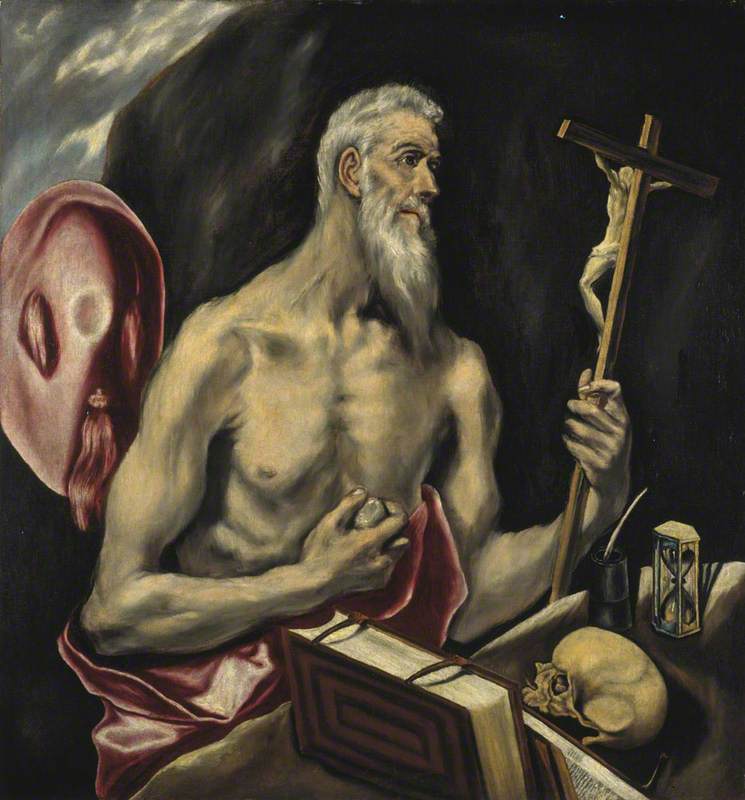

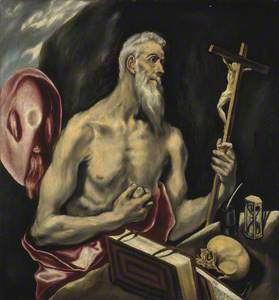

Later his paintings are looser and more expressive, his figures more sinuous and his highlights a stark and brash white. This is exemplified in the National Gallery of Scotland's Saint Jerome in Penitence (c.1595–1600), in which the wiry old saint beats his chest as he meditates on Christ's own suffering on the cross.

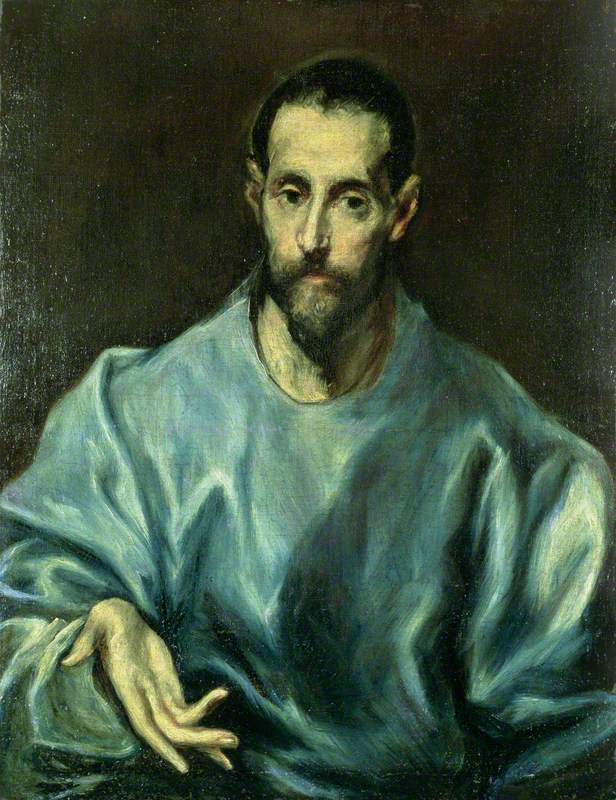

As El Greco's popularity grew, so too did his studio, with both the artist and his assistants creating various versions of the same composition. Particularly popular were painted cycles depicting each of the twelve apostles or the four evangelists. Saint John the Evangelist (1600) from the Schorr Collection (on long-term loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) and New College, Oxford's Saint James the Greater, were likely originally part of such a painted group.

El Greco died in 1614 and, beyond the borders of Spain, he was largely forgotten. It was only in the nineteenth century, first with the collecting of Spanish art after the Napoleonic Wars, and then with his 'discovery' by artists such as Édouard Manet, Cézanne and, later, Pablo Picasso, that his star once again began to rise. Echoes of El Greco's distorted anatomies, saturated colour and stark highlights can be found in the works of these modernist painters, yet it is his spiritual intensity that resonates most strongly through the ages.

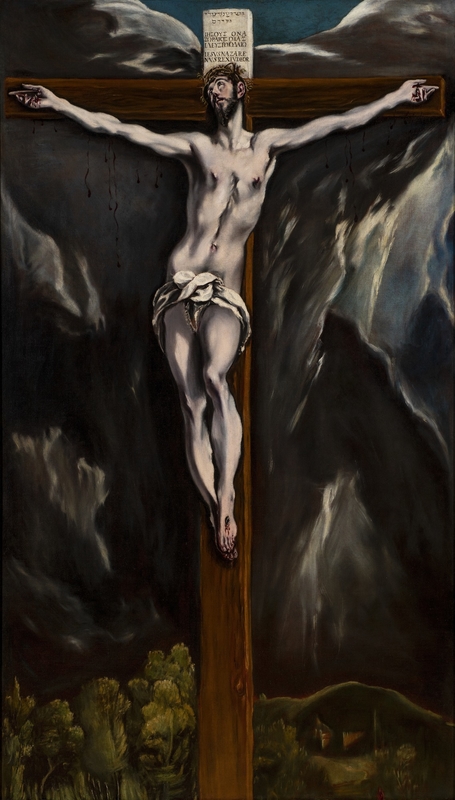

The public outcry of 1919 may be why El Greco's paintings are still fairly rare in British public collections. Indeed, the painting that caused the furore, The Agony in the Garden, is rarely seen as it was deemed a studio copy not long after its purchase. However, the tides may be turning. In 2015, with the help of the Art Fund, Christ on the Cross was bought for the new Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland. It is the first large-scale altarpiece by the artist to enter a public collection in Britain and well worth the pilgrimage to County Durham.

Isabelle Kent, art historian and writer specialising in Spanish art

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation