The canon of art history has been built on a myth – that of 'the genius'.

It's a myth that perpetuates the idea that the success of the world's greatest artists rests on their natural creative talent, above all else. A gendered term, genius is also the preserve of men, with the likes of Michelangelo and Manet, Rossetti and Picasso meeting its masculine criteria. Dreaming up ideas in isolation and driven by unstoppable originality, these individuals made 'masterpieces' alone in their studios, or so the story goes.

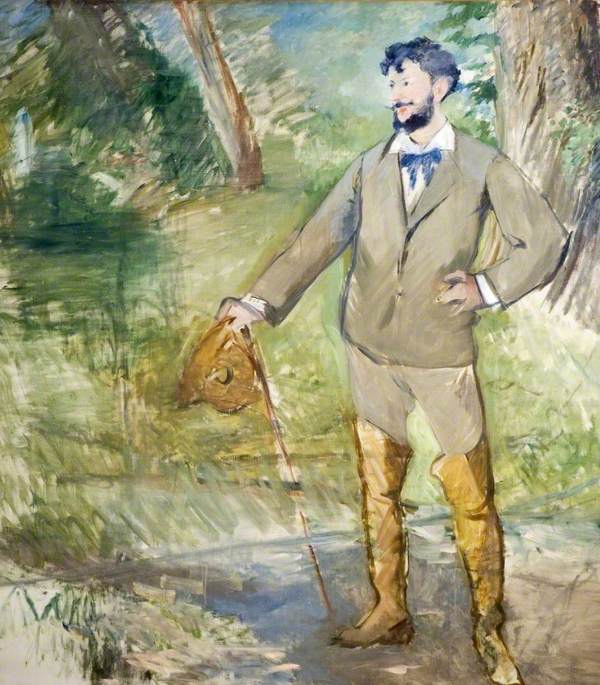

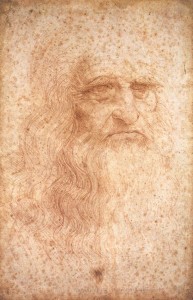

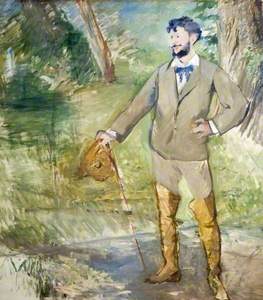

Study for 'Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe'

c.1863–1868

Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

But talent needs nurturing. As the feminist art historian Linda Nochlin famously pointed out, male artists were advantaged by access to formal arts education, while their female counterparts were barred.

Moreover, creativity isn't a solo pursuit, it's collaborative, as a spate of new exhibitions are showing audiences. From the National Portrait Gallery to Tate, museums are increasingly celebrating artist couples and the influence that has resulted from these significant partnerships, while platforming the contributions of the women involved. Working side-by-side, as mutual muses and coproducers, duos have supported and inspired one another, impacting subject, style and, as is frequently the case for the male artists, career success.

Through 'Discover Manet & Eva Gonzalès', The National Gallery invites viewers to see this pair, traditionally framed as model and master, as peers who had a transformative influence on each other's practice.

The French painter Eva Gonzalès entered the studio of Manet in 1869, aged 22, as his only pupil. At this time, Manet's career was stalling, with poor reviews of his Salon entries, but the presence of Gonzalès was hugely positive. Within a year, Manet had completed a portrait of her and successfully exhibited it with the title 'Mlle E.G.' at the 1870 Paris Salon, now named Eva Gonzalès and found in The National Gallery collection.

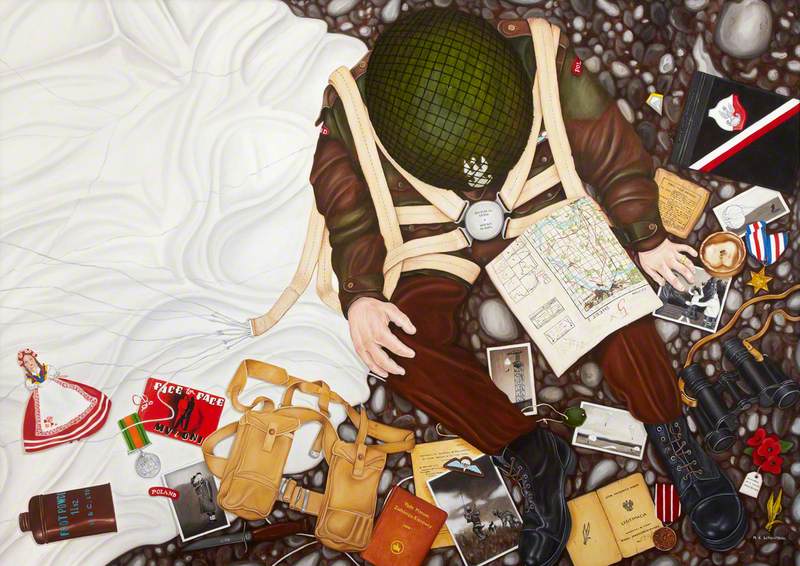

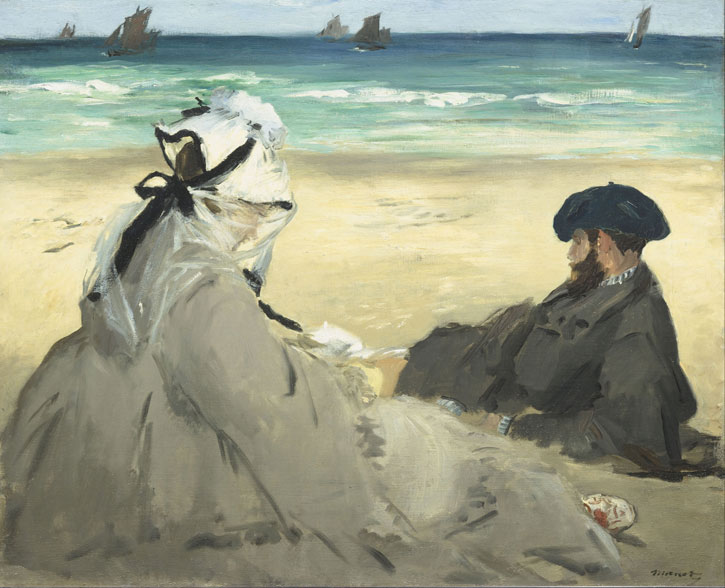

On the Beach

1873, oil on canvas by Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

Centre-stage in The National Gallery's exhibition, this portrait presents Gonzalès as an artist hard at work on a floral still life, with her portfolio propped up behind her. In the right-hand corner, Manet has included a rolled-up painting of his own – with his signature visible, he seems to be congratulating himself on a job well done, as her teacher. But he also seems to be reflecting on their close working relationship as artists in the same studio, where they naturally developed a shared artistic vocabulary.

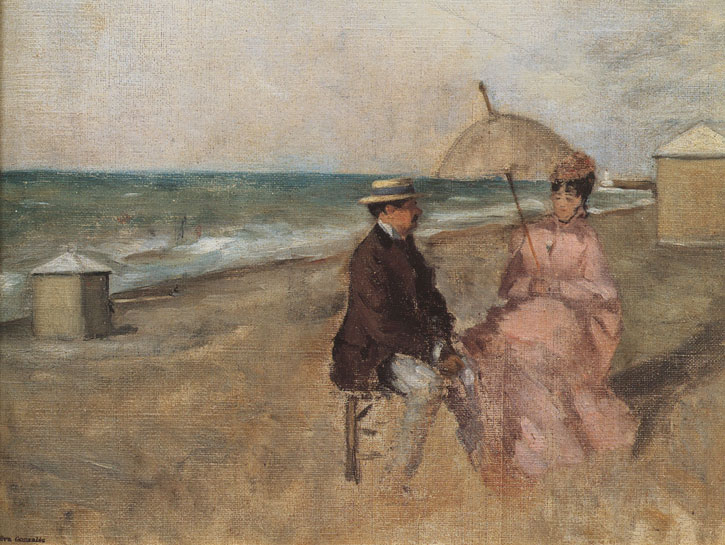

Study on the Beach (Étude sur la plage)

c.1875, oil on canvas by Eva Gonzalès (1849–1883)

Indeed, the pair's paintings developed at the same pace as they took subjects from everyday life, depicting them in the same sombre palette. Pairings include Manet's On the Beach, 1873, to which Gonzalès responded with Study on the Beach (Étude sur la plage), c.1875; then in 1880 she painted The Donkey Ride, echoed in Manet's later work, a portrait of Carolus-Duran in riding boots, from 1876.

In 1874, Manet made a pastel sketch, Couple in a theatre box, while Gonzalès painted A Theatre Box at the Italiens, in which a bouquet resting on the ledge very closely resembles the one being presented by the maid in Manet's Olympia, 1863.

Avec #DansNosCollections, notre équipe de conservation vous parle d'œuvres que vous ne connaissez peut-être pas encore comme...

— Musée d'Orsay (@MuseeOrsay) June 11, 2020

"Une loge aux Italiens" (1874) d'Eva Gonzales .#FemmeArtiste pic.twitter.com/BiitUyde7S

Olympia

1863, oil on canvas by Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

But Manet's success and legacy as a genius, sparked in great part by his artistic partnership with Gonzalès, has undoubtedly overshadowed her reputation as a painter. Moreover, she is still seen primarily through his lens and gaze, as The National Gallery's staging of her portrait by Manet proves.

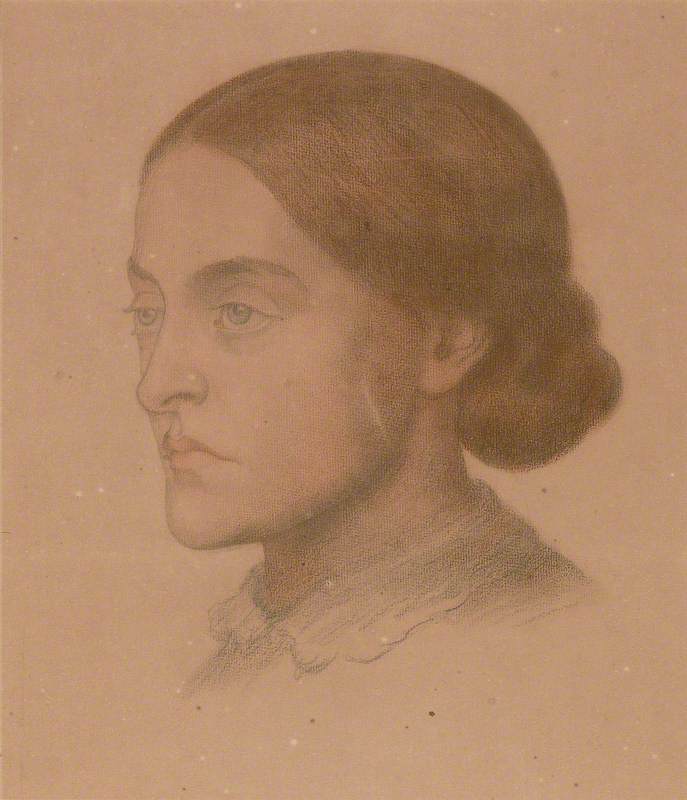

Likewise, Dante Gabriel Rossetti's identity as a great artist has historically overshadowed that of his creative and romantic partner, Elizabeth Siddal. However, an upcoming exhibition at Tate Britain, 'The Rossettis', seeks to rebalance this narrative, exploring the working and personal relationships between Dante Gabriel, Christina Rossetti and Elizabeth. It will be the first time that all the surviving paintings, major drawings and watercolours by Siddal will be shown to the public.

Today, Siddal is best known as an iconic muse and model for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, having posed for many of its members, including John Everett Millais, Walter Howell Deverell and Rossetti, whom she eventually married.

In her 1896 poem In an Artist's Studio, Christina reflected on the relationship between her brother and sister-in-law, while exposing the gap between the positions of man and woman, artist and model, in Victorian society: 'One face looks out from all his canvasses... A saint, an angel; – every canvas means / The same one meaning, neither more nor less. He feeds upon her face by day and night, / And she with true kind eyes looks back on him...'

But Siddal was also a talented artist and poet, and inspiration flowed both ways for this pair. 'The Siddal-Rossetti partnership was a mutual commitment to art, poetry and each other, despite the power imbalance that inevitably existed', explains curator, art historian and writer, Hannah Squire.

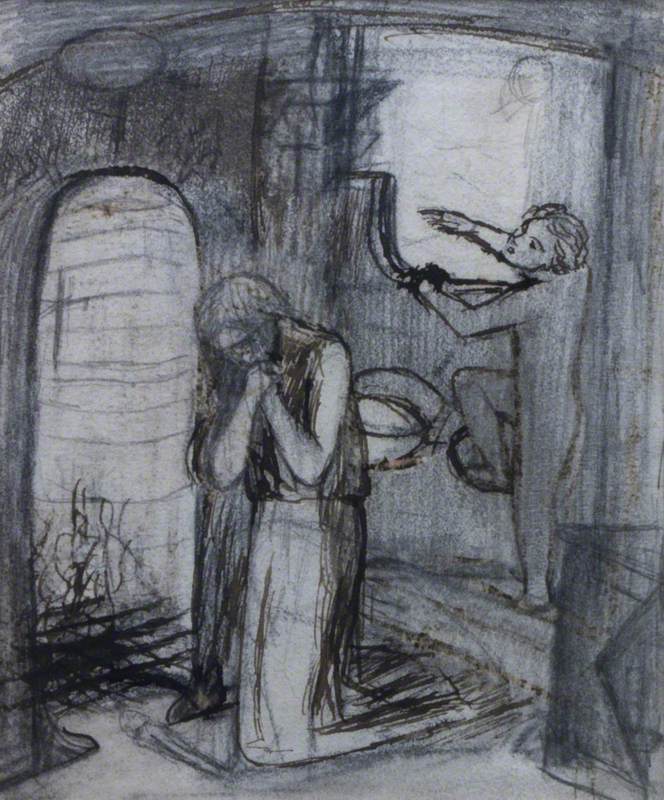

'They shared artistic commissions and created pieces of artworks together, harmonising their styles and ideas. When depicting the same figures their art is clearly inspired by each other's compositions. For instance, Siddal's drawing Sister Helen, 1860, is an artistic response to Rossetti's poem of the same name.'

Modern art has also been defined by countless creative partnerships: Marcel Moore and Claude Cahun, Emilie Flöge and Gustave Klimt, Gala and Salvador Dalí, Jo and Edward Hopper, Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz, and, of course, Picasso and his long line of artist-partners who also acted as muses.

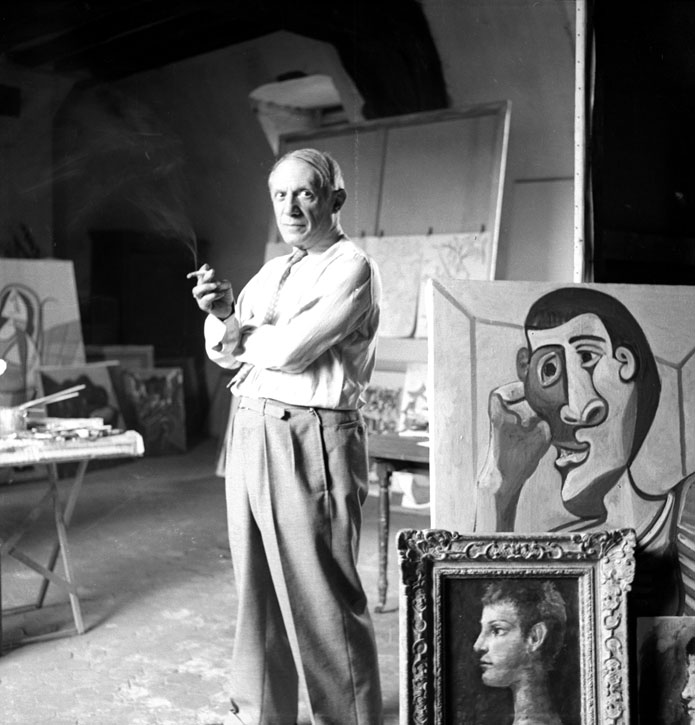

Picasso in his studio, Liberation of Paris, Rue des Grands Augustins, Paris, France

1944, photograph by Lee Miller (1907–1977)

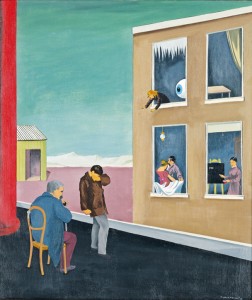

With their show, 'Lee Miller and Picasso', Newlands House are disrupting dominant narratives about the Spanish painter and his female models, to present Picasso as Miller's muse. 'I would rather take a photo than be one' said the American model turned Surrealist photographer turned war correspondent.

Miller first met Picasso in the summer of 1937 whilst holidaying in the South of France, after which he painted six colourful portraits of her, one of which, Portrait of Lee Miller as Arlesienne, 1937, she hung in her home.

Portrait of Lee Miller as Arlesienne, 1937 #picasso #pablopicasso https://t.co/Wi13u7nMO6 pic.twitter.com/bqORRmXdXF

— Pablo Picasso (@pablocubist) June 30, 2022

However, and discussed far less, Picasso also became an important muse for Miller, who photographed him more than 1,000 times in the ensuing years, as they became long-lasting friends. Many of her images present Picasso as a man and father, as well as an artist, visiting her in Sussex, where dressed in cap and boots, he can be seen on country walks and attending to the family bull, William, whom he later drew for a print that was used in the 1950s for a fundraising campaign for London's Institute of Contemporary Art.

Miller also gained access to Picasso's studio, a privilege awarded to only his closest circle. Her images of the site, both with and without Picasso inside it, accompany the Spanish artist's portrayals of it, as if he not only trusted her with his image, but needed her to affirm it. Constructing himself as a great art genius, Picasso often painted his studio as a sacred space where he, the master, conjured magic; 'inspiration exists but it has to find you working', he once declared.

Lee Miller and Picasso after the liberation of Paris, France

1944, photograph by Lee Miller (1907–1977)

Separated by the Second World War, the pair were reunited upon the Liberation of Paris inside Picasso's studio in Paris, which Miller headed straight to. Her poignant photograph shows them embracing and beaming into one another's faces. 'This is marvellous, this is the first Allied soldier I have seen, and it's you!' Picasso is reported to have said. Allies in art, both of whom endlessly reinvented their work, is exactly what these two were.

Contemporary art, too, has seen artists working in partnership, from Christo and Jeanne-Claude to Gilbert & George.

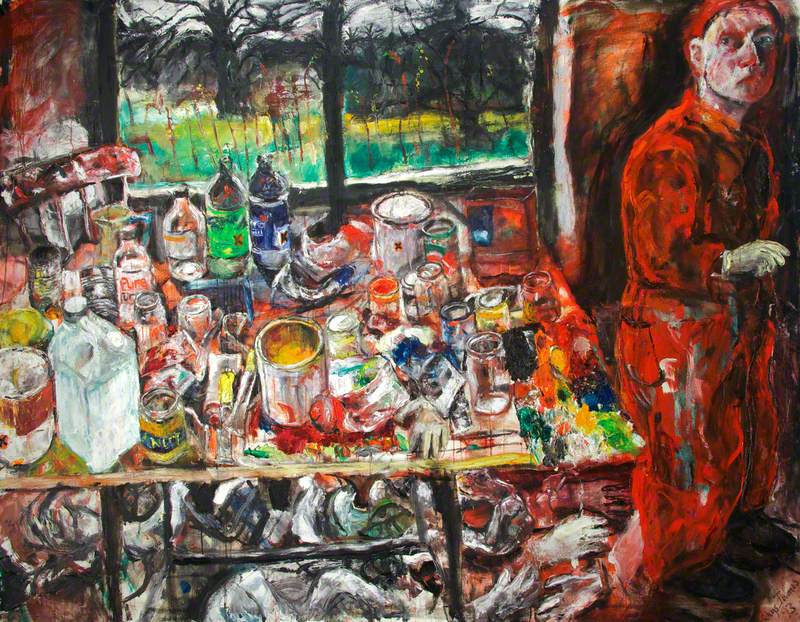

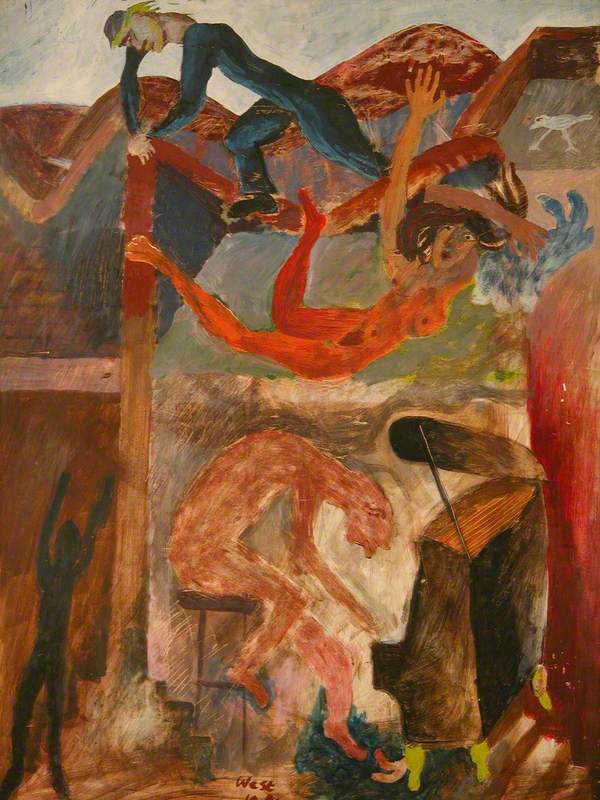

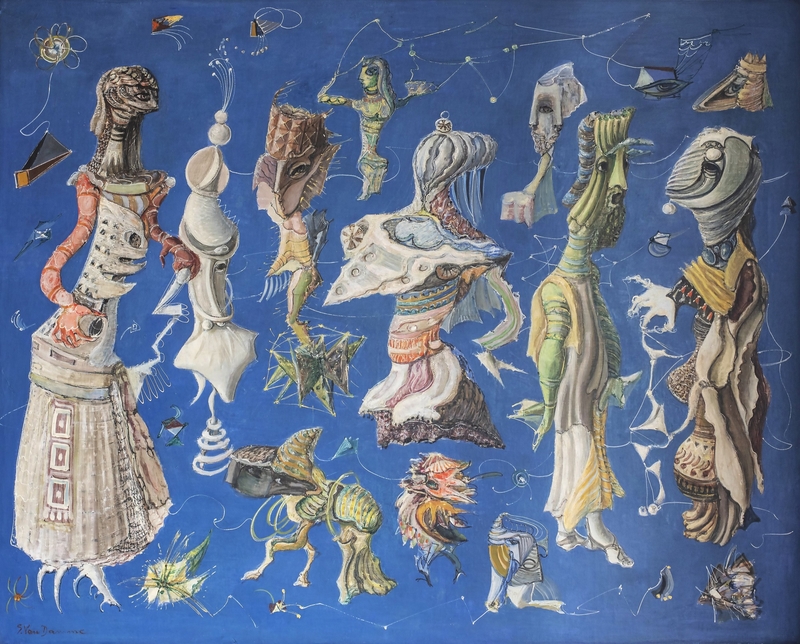

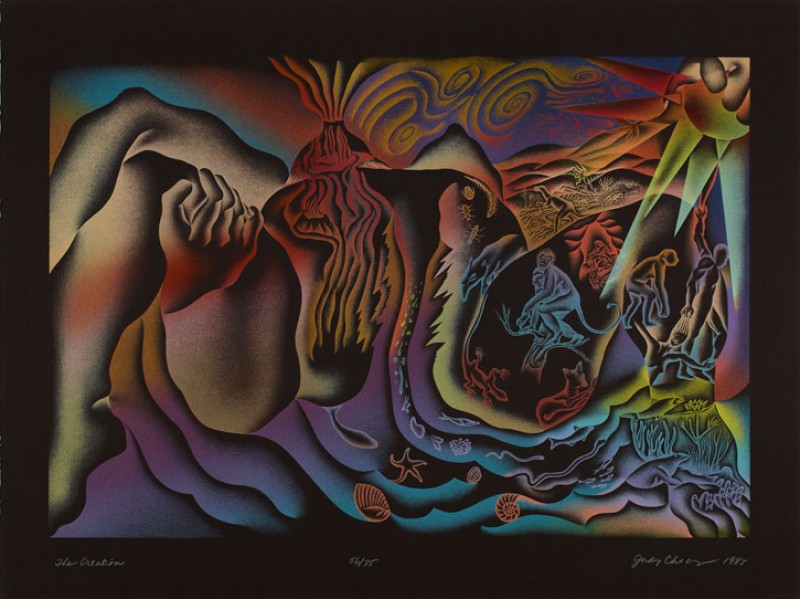

Among those with the most long-lasting of working relationships is the married couple Shani Rhys James and Stephen West. Their recent show, aptly titled 'Shared Space' at Oriel Davies, reveals a conversation of ideas, influences, inspiration and emotions, to be found in the shared subject matter – a garden ladder, their bed, a ceramic dish appear as symbols in two unique sides of the same story.

'When 2 people work alongside each other for 40 years there's going to be a lot of cross-over - but the artistic personalities remain distinct as each has to give the other space to think and create', says Stephen West. Rhys James is in agreement, 'We work in two separate studios linked by a door. We intuitively respect each other's space and both work in isolation. Occasionally we invite each other into our space with the refrain, 'what do you think?'.

Just as Rhys James and West acknowledge their mutual influence, so too are museums finally reflecting the notion of collective and creative exchange, over individualism, which has shaped art history. In cases such as that of Manet and Gonzalèz or the Rossettis, who worked in tandem, the result has been a synchronicity of approach, style and subject matter. For other pairings, collaboration has come in the form of emotional and practical support, as well as deep friendship; the likes of Miller and Picasso spurred one another onto success through their reciprocal relationship, in which they were equal muses.

By deconstructing the myth of the great art genius, museums can importantly show audiences that many, if not most, masterpieces cannot be understood simply as the work of one pair of hands. Rather, art's superstars have worked in partnership, relying on the assistance of others, and often women, whose contributions have historically been downplayed, overlooked and even obscured, despite the fact that they frequently acted as an equal force in their duos.

Acknowledging such influence, it's evident that the story of art has not been created by masters in silo but rather in creative collaboration, and often with women.

Ruth Millington, art historian and freelance writer

Further reading

Jane Alison and Coralie Malissard, Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-Garde, Prestel, 2018

Ruth Millington, Muse, Vintage, 2022

Linda Nochlin, Representing Women, Thames and Hudson, 2019

Hannah Squire, 'Beyond Ophelia' – A Celebration of Lizzie Siddal, Artist and Poet', National Trust