Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569) was the leading artist of his time in Northern Europe. He left a collection of works of remarkable detail and vivacity, showing a world of busy, everyday life. Not for him the idealised beauty of the warm south: Bruegel's world is an earthy, earthly place.

Most of Bruegel's works are in Europe – the finest single collection being in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. In the UK, The National Gallery houses The Adoration of the Kings (1564), the British Museum has a rich collection of drawings and prints, while the Courtauld gallery is home to Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (1563) and the atmospheric and sculptural grisaille, Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1565).

Christ and the Woman taken in Adultery

1565

Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

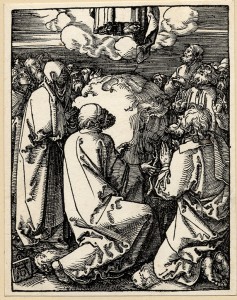

Bruegel's determination to portray the world authentically meant that when he took on mythical or religious subjects – which was relatively rare – he staged these in the recognisable settings of the Flemish village and countryside, with a cast of unprepossessing rural folk.

Bruegel's distinctive vision often places the ordinary at its centre and displaces what would normally be the focus of attention. Important figures, whether royal, religious or mythical, are diminished or marginalised. Bruegel's art makes the plain people his subject, and questions grandiosity. It deflates pride and pomposity.

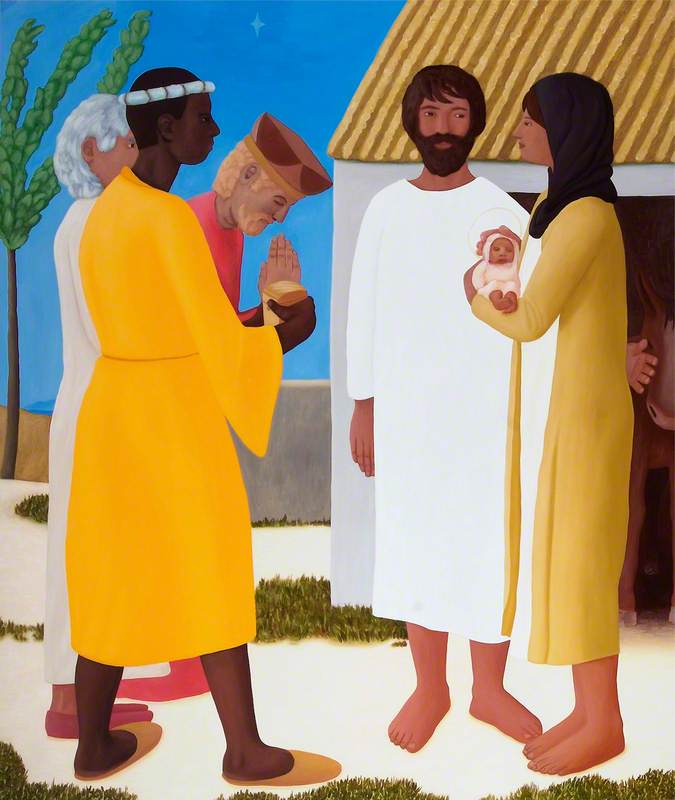

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

John Berger called Bruegel 'the most unforgiving artist who ever lived'. Berger had in mind Bruegel's portrayal of human indifference. This indifference is seen in the famous ploughman, unaware of plunging Icarus, in Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (c.1560), or in the marginalisation of Mary and Joseph in Landscape with the Flight into Egypt (1563), where a vast panorama overwhelms the travelling family, and we only see the back of Joseph disappearing down the hill.

Landscape with the Flight into Egypt

1563

Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

In Bruegel's other Adoration – the wonderful Adoration of the Kings in the Snow (1563) – the Holy family and the kings are only just within the picture space in the lower-left corner. It is the townspeople wrapped up against the cold in a marvellously rendered snowstorm who seem to be the painting's subject. Bruegel's religious subjects 'almost disappear into their painted settings, as Bertram Kaschek puts it.

Adoration of the Magi in a Winter Landscape

1567, oil on panel by Pieter Brueghel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Another notable example is Bruegel's Christ Carrying the Cross (1564), in which we have to search for the tiny figure of Christ stumbling toward Golgotha, barely visible in the centre of a mass of moving people. The crowd streams towards the execution like fans heading for a football match: their apparent unconcern for the gravity of events is shocking.

Christ Carrying the Cross

1564, oil on oak wood by Pieter Brueghel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Bruegel's tendency to give the ordinary greater prominence than the extraordinary led Aldous Huxley to characterise the artist as 'a [resolutely] human onlooker', in contrast to those artists who 'have pretended to be angels, painting the scene with a knowledge of its significance'.

The National Gallery's The Adoration of the Kings is just as unconventional in its way, being quite different from the standard serene, photogenic, angel-attended spectacle. It does show, however, the influence of Italian composition (for example, see Carlo Dolci's Adoration). Its vertical format and large, dominating figures are noteworthy: it is the only painting by Bruegel in this format, and the first of his oeuvre to contain large-scale figures.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

A cast of gawping bystanders (one scholar refers to their 'bovine amazement') attend upon the squirming babe. This Christ Child has attracted a pressing crowd of village folk and armed men whose weaponry stabs the grey sky. A giant soldier leans forward behind Mary, all agog, and the heavy mass of the stable appears to lean in with him, bearing down on the Holy family. It adds its great weight to the sense of oppressive encirclement, and seems to bode no good.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

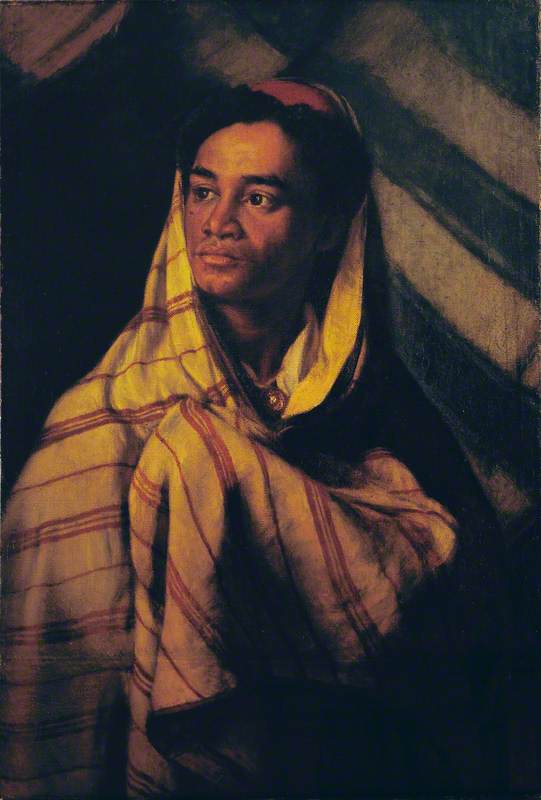

Completing the disturbing circle are the three kings. The crouching older king causes the babe to flinch, while his younger but no more appealing colleague waits grimly by to offer his gift. Only the Black magus keeps a distance, but stares out of the picture, as if distracted.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Old Joseph stands behind his wife. But there's no look of pride on his face. Rather, he listens as someone whispers in his ear. What secret is this? What gossip? Is it, as some scholars claim, tittle-tattle concerning Mary's fidelity? The age difference of the Holy couple in itself would set some tongues wagging. Others point out the broad-brimmed hat he holds and wonder at its significance.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Returning to Berger's idea, there's a kind of innate indifference to be found in the depiction of the cast of the Adoration. It is their unbecoming vulgarity, their ugliness, their inquisitiveness, perhaps even their covetousness – all in all, their plain humanity – which betrays an expectation for something more beautiful and in keeping with this hallowed episode.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

We might ask if it was Bruegel's intention to greet the newborn Christ with unpleasantness and menace. It may seem so. The presence of so much weaponry – the pikestaffs, the swords, the crossbow – signals the eternally warring world. Scholars are fond of finding unsettling, sinister signs in this painting: the crowd, threateningly close, ogle the expensive gifts, while the kings are ugly and scary (one writer calls them 'a disreputable crew'), and the whispering man dispenses malicious gossip.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

This line of thought even extends to the position of Joseph's hat, held – in a way that signals his impotence – over his defunct loins, and the absence of an ox alongside the ass, which seems to bray in distress. Most obscure of all, a study has been made of the designs embroidered into the old king's robe, which include a centaur, sirens and a sphinx. These images, it is claimed, identify this king as 'totally ruled by the forces of evil'.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

One critic's interpretative imagination extends to the cross-shaped head of the tall soldier's pikestaff, which is seen as an allusion to the cross upon which Christ will be crucified, an idea reinforced by its central position over the babe's unknowing head. Even the staring eyes of the onlookers, wide we might think with wonder and curiosity, may be read as suggesting anger or madness.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Taken together, what are we to make of these effects? They might add up to a subversion of this most precious Biblical scene – a demotion of the Holy to the very earthly – indicating a questioning attitude to religious orthodoxy. Max Dvorak, who wrote elegantly on this painting, saw it rather as a new way of representing religious faith: not a remote, beautified version of events, but rather a down-to-earth view of 'the spiritual life of ordinary people'. It is the very stiff and gawky presence of the curious crowd that both makes us smile and makes us believe in them.

Detail of 'The Adoration of the Kings'

1564, oil on oak by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Bruegel was concerned with unvarnished truth. Ugliness is not a sin, nor is curiosity, and need not mean anything is wrong. The cast of characters are Bruegel's own people – plain, Flemish types – and ordinary folk are often not beautiful, are indeed wrinkled, white-haired, short-sighted, nosy, severe. Even Mary is a heavy-set country girl, encouraging her baby to look at the offerings with a gesture of her large right hand. The child's uncomfortable reaction to being approached by a strange old man bearing gifts seems only natural.

Compared with so many ethereal and romanticised Nativities and Adorations, Bruegel's shocks us by simply being true to life.

And life isn't picture perfect, Bruegel seems to say.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Walter S. Gibson, Pieter Bruegel and the Art of Laughter, University of California Press, 2006

Bertram Kaschek, Pieter Bruegel the Elder and Religion, Brill, 2018

Manfred Sellink (ed.), Bruegel: The Master, Thames & Hudson, 2018

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.

.jpg)