The Belgian artist James Ensor (1860–1949) wrote of his dread of 'the eternal black night, death under the colourless earth'. Art was his greatest satisfaction, yet his own mortality, as he knew well, would rob him of this and leave him with nothing.

Image credit: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, CC0

Ensor at his Easel

1890, oil on canvas by James Ensor (1860–1949)

These are the thoughts of a man without the consolation of religion, an artist whose work is full of the signs and symbols of death. In a print made when he was just 28, he visualised himself as a rotting corpse, as he imagined he would be in 1960.

Although Ensor spent almost his entire life in the coastal town of Ostend, he complained bitterly about the place, describing it as 'monotonous' and inhabited by 'a public of oysters' who 'don't want to see painting'. Belgium was where he wanted to be, but 'The Land of Milk and Honey' was also 'The Land of Contempt'.

Contradiction is key to the idea of 'Belgitude', a term coined in the 1970s that defines the Belgian soul as essentially ambiguous and paradoxical, and preoccupied with derision, self-deprecation and morbidity. Stéphane Spoiden argues (in symplokē) that Ensor's work is typically Belgian in its counterbalancing of morbidity and humour.

Image credit: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, CC0

The Intrigue

1890, oil on canvas by James Ensor (1860–1949)

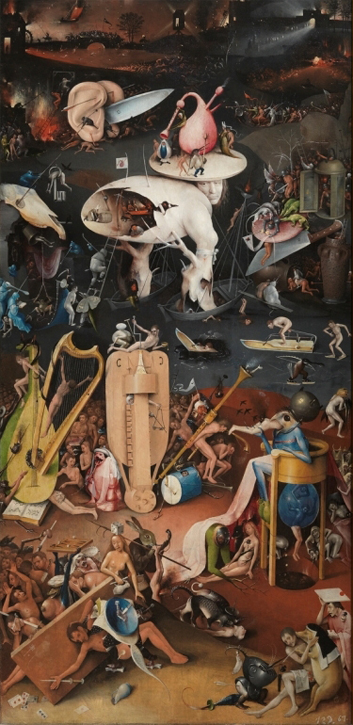

In fact, the resulting tone of derision achieved through the grotesque is characteristic of Netherlandish art through the ages, and Ensor's work has many echoes of his great Netherlandish forebears, Hieronymous Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the elder.

Image credit: Museum voor Schone Kunsten Gent, public domain

Christ Carrying the Cross

c.1510–c.1516, oil on panel by Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450–1516) or a follower

Ensor particularly admired Bruegel, whom he celebrated as: '… the master of deliverance, the master tickler of Brabant self-esteem, the master awakener of our national malice and zwanze farce, the quintessential liberator, the picture-maker dear to our little children. He is God to us all…'

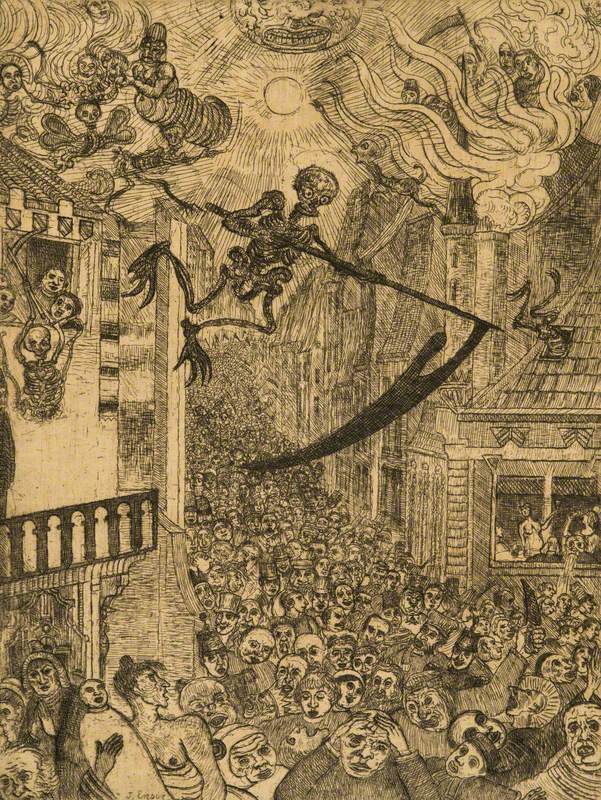

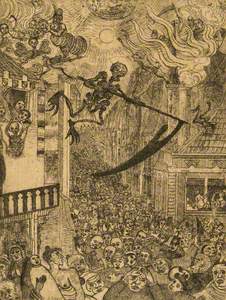

There are surprisingly few works by Ensor in UK collections. The 1896 etching La mort poursuivant le troupeau des humans (or Death Chasing the Flock of Mortals), in The Higgins Bedford, has startling parallels with Bruegel's The Triumph of Death (1562–1563).

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain

The Triumph of Death

1562–1563, oil on panel by Pieter Brueghel the elder (c.1525–1569)

In each, death is represented by skeletons who terrorise the mass of desperate human souls. Scythes are wielded, and there is in common a sense of futile panic. While most seek vainly to avoid the inevitable, there is in each picture a marginal scene of defiance – or distraction. In the lower-right corner of the Bruegel, a young man serenades his love: she seems entranced, but there is anguish in his expression. The equivalent cameo in the Ensor is to be found in the window of the building to the right, in which we see a bare-breasted woman raising a glass to her companions, one of whom vomits into the street.

These are images of a godless world, without salvation. Bruegel's army of skeletons herds the crowd into a huge box, an outsized coffin, literally signifying an earthly end. We imagine a similar fate awaits the surging mass in Ensor's work. In the skies above, there is no heavenly promise. Over a blazing sun, the lower half of a vast gurning face provides no comfort.

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain

Detail of 'The Triumph of Death'

1562–1563, oil on panel by Pieter Brueghel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Serving as Ensor's model, The Triumph of Death is remarkable for being almost entirely populated by adults. Only one child can be seen: a babe in arms, sniffed by a starving dog, its mother face down, cowering, or dead. Ensor has apparently noticed this and also includes just one child: a baby carried by its mother, who looks back fearfully. Why did Bruegel (and then Ensor) choose to remove children from their visions of hopelessness? Perhaps they did not think it right to subject innocence to such grim reality.

Image credit: The Higgins Bedford

Detail of 'La mort poursuivant le troupeau des humains'

1896, etching on paper by James Ensor (1860–1949)

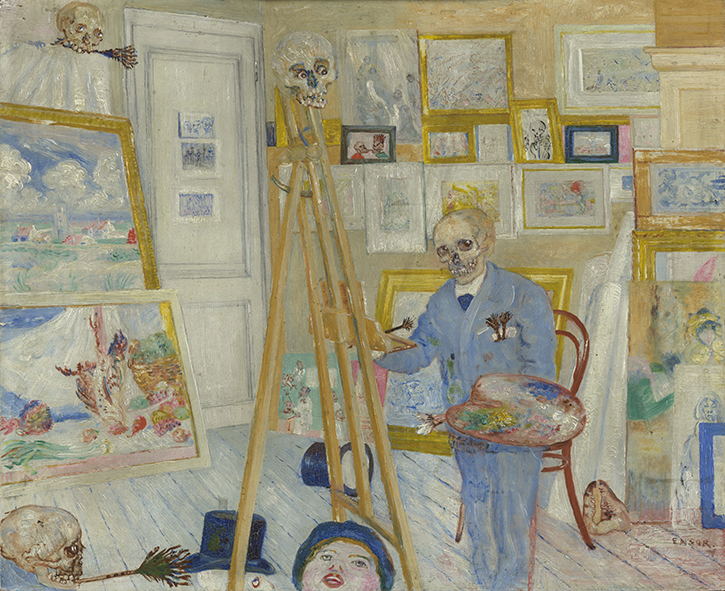

In referencing Bruegel, Ensor's picture shares a motif that he made very much his own and which haunts his oeuvre: the animate skeleton. Skeletons in Ensor are reminders of the proximity of death, but Ensor exploits their dual visual effect of being both macabre and darkly comic.

In The Skeleton Painter, Ensor presents himself in his studio, working at his easel, but his head is replaced by a skull, and other skulls oversee his work. Death stalks the artist. The transience of the creative life was a source of anxiety for Ensor. Even as a young man, he was fearful of death and the loss of his art: 'Thoughts of survival frighten me. The transitoriness of the painting material gives me cause for worry'.

Image credit: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, CC0

The Skeleton Painter

1896, oil on panel by James Ensor (1860–1949)

While skulls and skeletons clearly obsessed Ensor, their significance is not simply that of memento mori. Ensor delights in the disturbing mix of reality and imagination. This tendency reaches back to the fantastical works of Bosch and Bruegel – and to his own childhood. Arrangements of disparate items were found in the bric-a-brac shop that his parents owned in Ostend. As Ensor wrote:

'I spent my childhood in the paternal shop surrounded by curiosities from the sea and the splendours of mother-of-pearl with a thousand iridescent gleams and bizarre skeletons, monsters and marine plants. The proximity of these wonders, the colours, this light-filled, gleaming opulence undoubtedly helped turn me into a painter in love with colour and sensitive to the dazzling play of light.'

And beyond his concern with colour and light, the shop's miscellany of strange, incoherent objects (including carnival masks for hire) surely had a hand in Ensor's weird – and often claustrophobic – compositions. Bosch, of course, had juxtaposed curious and incongruous objects in his surreal visions.

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain

Detail of 'The Garden of Earthly Delights' (triptych, right wing)

1490–1500, grisaille, oil on oak panel by Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450–1516)

The skull, by virtue of lacking lips and skin, has a permanent grin of derision. It seems to mock all it sees (though it mocks us by making us think it sees at all). This gives Ensor's many skeleton-haunted works much of their unsettling power.

The mask, the other well-known trope of his art, shares with the skull a single, fixed expression. As Porcelaines et masques (in The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) shows, it seems that Ensor could not paint a still life without the faint spectres of masks in the background.

Both skulls and masks present to the world an inscrutability that belies the normal candour of the face, giving an amoral atmosphere to his pictures.

Image credit: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, public domain

Masks Confronting Death

1888, oil on canvas by James Ensor (1860–1949)

Derision is a major theme in Ensor's work. Isolated figures, surrounded by intimidating, leering faces, occur repeatedly. In Masks Confronting Death (1888), sometimes known as Masks Mocking Death, it is the skeleton which is outnumbered. But the mockers are masked: they need a disguise to match the skull's grotesquery and face the spectre of death.

Much of Ensor's art is devoted to mockery and victimhood, often his own. His best work was made in the first half of his life, when it was often met with rejection or indifference. Appreciated by neither the crowd nor the critics, he developed a powerful sense of persecution.

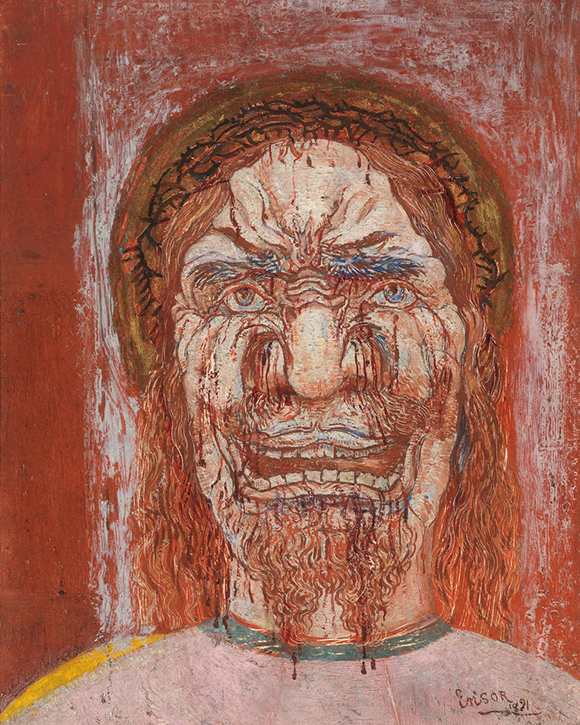

His identification with torments of Christ, who features in several works, reaches its apotheosis in a drawing of 1886, Calvary, or Ensor on the Cross (in a private collection), in which it is Ensor himself who is crucified at Golgotha, his side pierced by a lance bearing the name of one of his fiercest critics, Edouard Fétis. And Ensor is the de facto subject of The Man of Sorrows.

Image credit: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, CC0

The Man of Sorrows

1891, oil on panel by James Ensor (1860–1949)

In other works, Ensor depicts himself surrounded by grotesque tormentors, while he looks out at us with sadness and dignity, the victim of a cruel world.

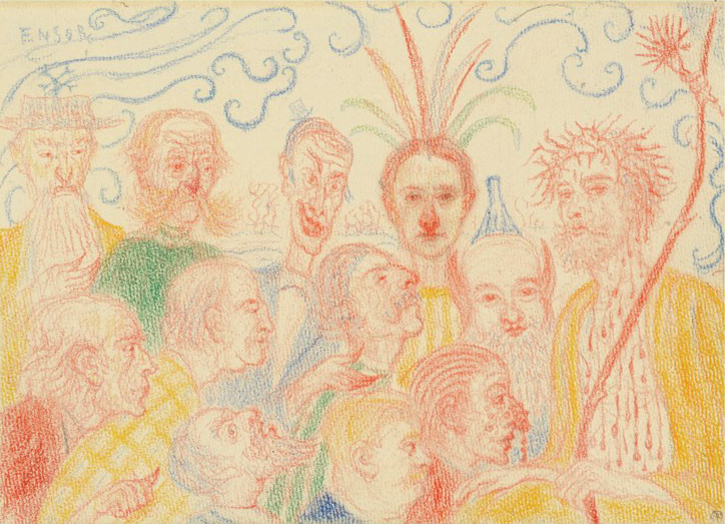

Image credit: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, CC0

Christ before his Judges

1921, coloured pencil & wax crayon on paper by James Ensor (1860–1949)

The obvious precursor is Bosch's Christ Mocked, in The National Gallery.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Christ Mocked (The Crowning with Thorns) about 1490-1500

Hieronymus Bosch (c.1450–1516)

The National Gallery, LondonEnsor made numerous works with Biblical themes, causing his fellow artists to complain about his choice of archaic religious subject matter. But much of this imagery is autobiographical, presenting his own troubles and allowing expression of his sharply satirical outlook.

Accounts suggest that Ensor was thin-skinned, moody, sarcastic and at times aggressive. Although he dismissed the people of Ostend for not recognising his talent, it is typical of his love-hate relationship with his hometown that he was offended when the artist Léon Spilliaert remarked that 'Ostend was not the world'. For Ensor, somehow it really was.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

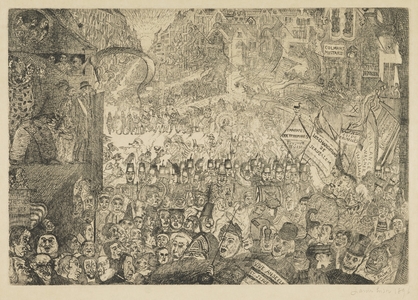

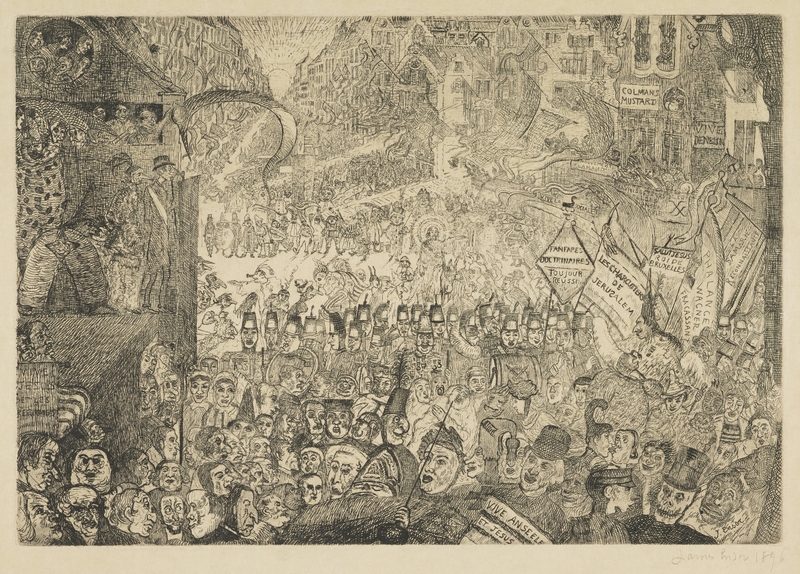

L'entree du Christ a Bruxelles (The Entry of Christ into Brussels) 1896

James Ensor (1860–1949)

National Galleries of ScotlandIn 1888–1889, Ensor painted an important work on a very large scale, The Entry of Christ into Brussels. An etching based on the picture is in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh. The haloed figure of Christ is accompanied into the Belgian capital by a coarse, pressing crowd, populated by masked and grotesque figures. As Ensor said, 'here swarm all the little hard and soft creatures spit up by the sea.'

There is a striking similarity with Bruegel's Christ Carrying the Cross of 1564. Both artists locate a Biblical episode in a contemporary setting, and in each work the figure of Christ is reduced to a detail in the middle of a progressing crowd.

Image credit: Kunsthistorisches Museum, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Christ Carrying the Cross

1564, oil on oak wood by Pieter Brueghel the elder (c.1525–1569)

Each work is a vast panorama of human indifference that gives prominence to the ordinary over the exceptional. In the Ensor, while there is a triumphal quality to Christ's arrival, the crowd engulfs the vulnerable figure, prefiguring the torments to come. Ensor's identification with Christ harbours both a threat and a fantasy of long-sought recognition. After all, Ensor saw himself as the 'revivifier of Belgian art' who might one day 'enter victoriously into the capital'.

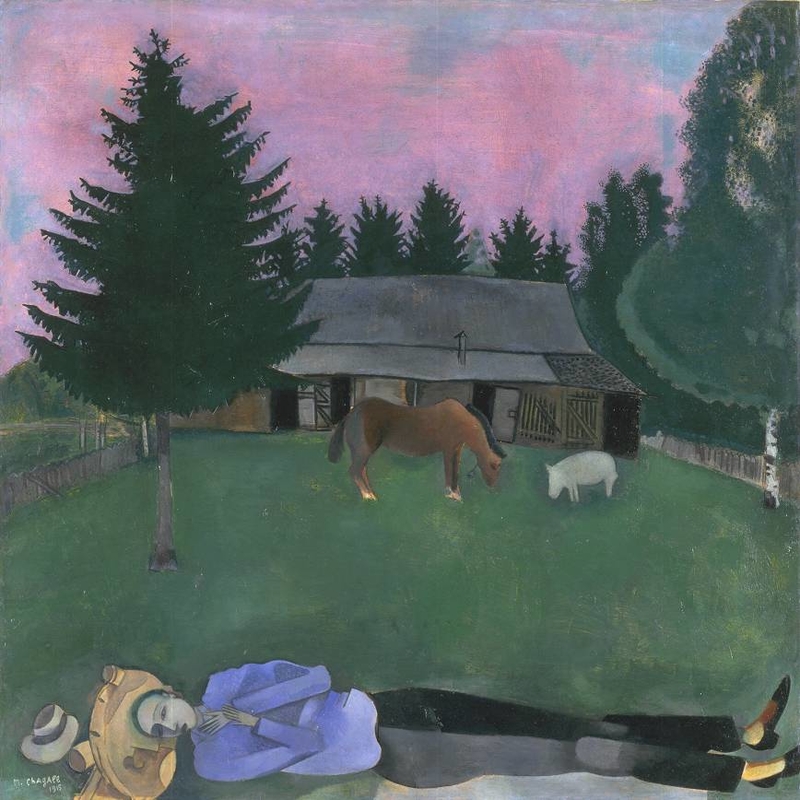

Ensor's artistic career – so embittered and yet so powerfully productive until the turn of the twentieth century – endured a long, uninspired coda that lasted half his lifetime. Much of his later work is mediocre, among which are pale copies of earlier successes.

Image credit: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, CC0

Azaleas

1920–1930, oil on canvas by James Ensor (1860–1949)

Attempts at explaining this include Diane Lesko's suggestion that Ensor suffered from the disturbing influence of one Augusta Boogaerts. She seems to have become, in Lesko's words, Ensor's 'unofficial business manager', duties which extended to arranging the objects for 'banal' still life compositions. Lesko claims that Boogaerts's assertive feminism disturbed Ensor, who turned to writing misogynistic poetry. Another theory connects his diminished creativity to low self-esteem, as expressed in psychoanalytical terms.

However, a less insidious explanation is the plain fact that the decline in the quality of Ensor's work coincided with long-coveted recognition. Significant success came in his mid-40s, and perhaps with this, his art, so long nourished by a sense of persecution and frustration, lost its fire.

Image credit: Philadelphia Museum of Art, public domain

Self-Portrait with Masks

1937, oil on canvas by James Ensor (1860–1949)

In a late self-portrait from 1937, a column of four masks – two of which look quite bewildered, while another may be sleeping – keep a safe distance from the elderly Ensor, who turns to us with a gentle smile. The paintbrush he holds seems to ward off these mild demons, and then we realise he is in the act of painting them on a grey-green background: they are no longer actual presences – the threat is over.

Ensor lived a long life. Over his remaining years, he received various honours, including a barony in 1929. He met Albert Einstein, in exile from Nazi Germany, at a restaurant near Ostend. After Einstein had tried, and failed, to explain his theory of relativity, Einstein asked what Ensor painted, and Ensor replied 'Nothing'.

From the artist for whom art was everything, another contradiction.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Ulrike Becks-Malorny, Ensor: Masks, Death and the Sea, Taschen, 2000

James N. Elesh, The Illustrated Bartsch: James Ensor, Abaris Books, 1982

Diane Lesko, James Ensor: The Creative Years, Princeton University Press, 1985

Xavier Tricot, James Ensor: Chronicle of his Life, Yale University Press, 2020

Luc Tuymans, James Ensor by Luc Tuymans, Royal Academy of Arts, 2016