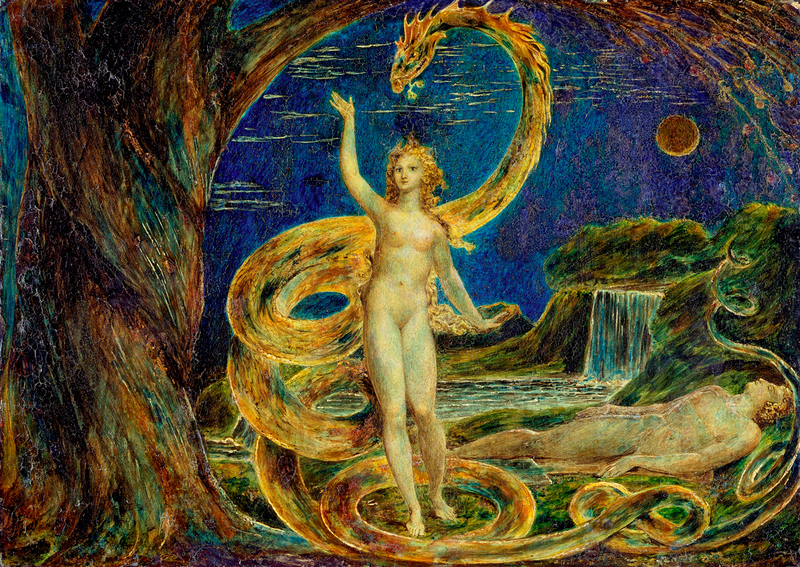

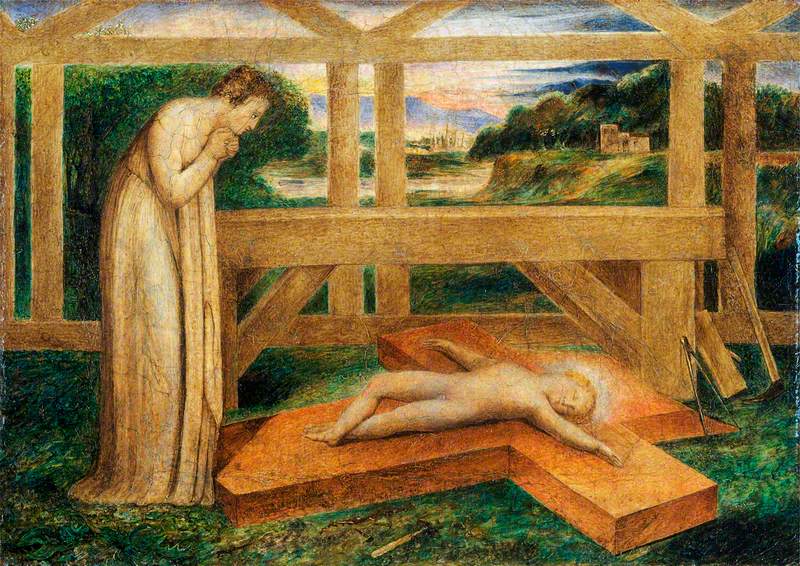

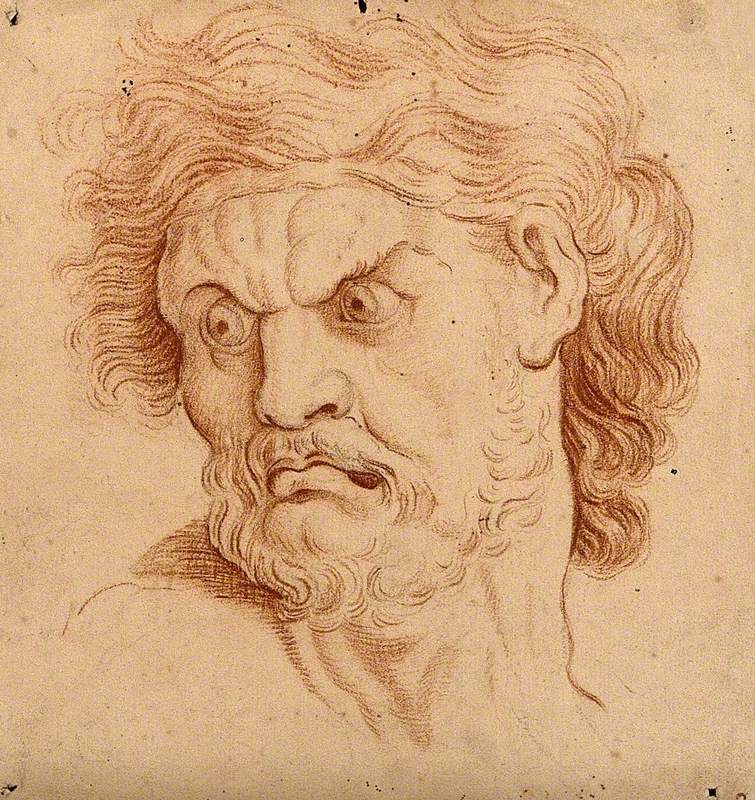

William Blake (Born London, 28 November 1757; died London, 12 August 1827). English printmaker, painter, poet, and mystical philosopher, one of the most remarkable figures of the Romantic period and one of the supreme individualists in the history of art. He was equally gifted in poetry and the visual arts, and in both fields he worked in a highly original, deeply personal idiom that expressed his idiosyncratic views and fiercely independent personality. His unorthodoxy was bound up with his hatred of materialism and rationalism, which he thought fettered the mind and spirit and led to misery and oppression. He was deeply religious and frequently depicted Christian subjects in his paintings and prints, but he used private as well as traditional imagery, with complex—often obscure—symbolism reflecting his wide and varied reading, and he came to regard art, imagination, and religion as indivisible. In matters of technique he was just as original, developing new methods of printing to publish his poetry and pictures together. He had a few loyal patrons and admirers, but for most of his life he struggled to earn a living, being ignored or dismissed as eccentric (or mad) by the world at large. It was not until long after his death that he was widely recognized as one of the great men of his age.

Blake claimed that he was helped to solve the technical problems of creating his books by the spirit of his beloved younger brother, Robert, who died of consumption in 1787, aged 19. In the practical business of hand-tinting and binding the pages he was assisted by his devoted wife Catherine. Apart from some experimental booklets, Blake's first publication using his new method was Songs of Innocence (1789). In 1794 he added Songs of Experience, never issuing this separately, but always bound with the first volume to make Songs of Innocence and of Experience. The two parts were intended to show the ‘two contrary states of the human soul’: Songs of Innocence are meditations on childhood, whereas Songs of Experience (which include the celebrated ‘Tyger, Tyger’) deal with the corruption of innocence by adult life. Blake used several other techniques in his work. He avoided oils, which he thought encouraged blurring of forms, as clarity of line was essential to him (he saw his visions—whether of angels or his dead brother—so intensely that they seemed part of the real world). For paintings he sometimes used tempera (confusingly he called the medium ‘fresco’), which he associated with the predominantly linear style of the early Renaissance, and in printing he produced some outstanding wood engravings.

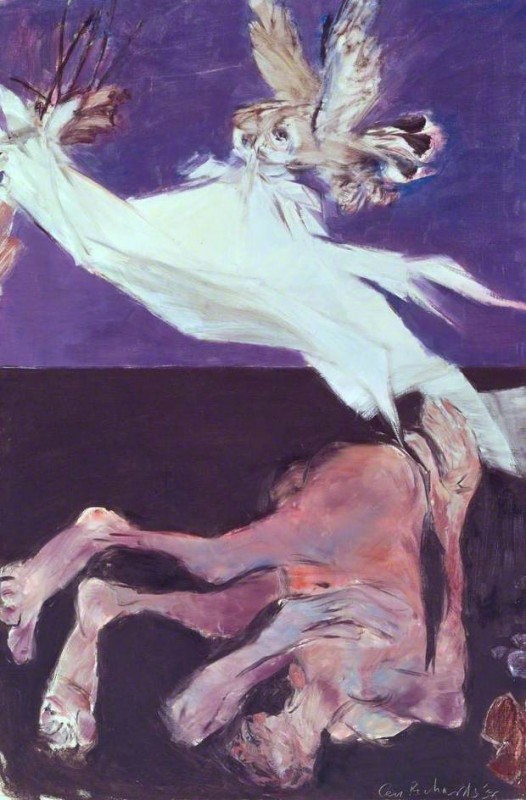

In 1795 he began a series of monotypes that are usually referred to as the ‘Large Colour Prints’. Twelve are now known; the subjects derive from the Bible, Milton, and Shakespeare, as well as from Blake's own writings, and the overall theme (if there is one) is uncertain. They have no accompanying text and in them Blake emerges for the first time as a great visual artist independent of Blake the writer (Elohim Creating Adam, 1795, Tate, London). None of these ‘colour printed drawings’ (as Blake called them) is known in more than three impressions, and the technique perhaps appealed to him more for its textural qualities than as a means of reproducing his work. In about 1795 Blake was introduced to Thomas Butts, a civil servant who became his main patron for many years, paying him what was virtually a regular wage. He had a less happy relationship with another patron, the poet and biographer William Hayley, who (through Flaxman's agency) employed Blake from 1800 to 1803 at his home at Felpham, on the Sussex coast—the only time he lived outside London. The work provided by Hayley (such as decorating his library) was ill-suited to Blake's temperament and he described his employer as ‘a corporeal friend and spiritual enemy’. After the interlude in Sussex he found it harder to pick up commercial engraving work, and in 1809–10 he mounted an exhibition of his paintings and drawings in an effort to appeal directly to the public. Few people came to see it and the only review described Blake as ‘an unfortunate lunatic’.

In 1818 he met his second great patron, John Linnell, and largely thanks to him, his final decade was comparatively free of financial worries and one of the happiest and most productive periods of his life. His work for Linnell included a series of watercolour illustrations to Dante's Divine Comedy, begun in 1824 and left unfinished at his death. These include some of his finest work, in which he reached new heights in radiant use of colour and in the rendering of visionary experience. Linnell introduced Blake to a circle of idealistic young artists—the Ancients—who admired him and his work and brought to his old age a degree of protective sympathy he had never known before. One of them, George Richmond, said that he ‘died like a saint…singing of the things he saw in heaven’. In the next generation his memory was kept alive by a few admirers (including Rossetti—another painter-poet with mystical leanings), but when the first substantial biography of him appeared in 1863—Alexander Gilchrist's Life of William Blake—it was subtitled ‘Pictor Ignotus’ (the unknown painter). The centenary of his death in 1927 stimulated a major revival of interest, and thereafter his reputation grew rapidly. His vast output now supports an academic industry of its own.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)