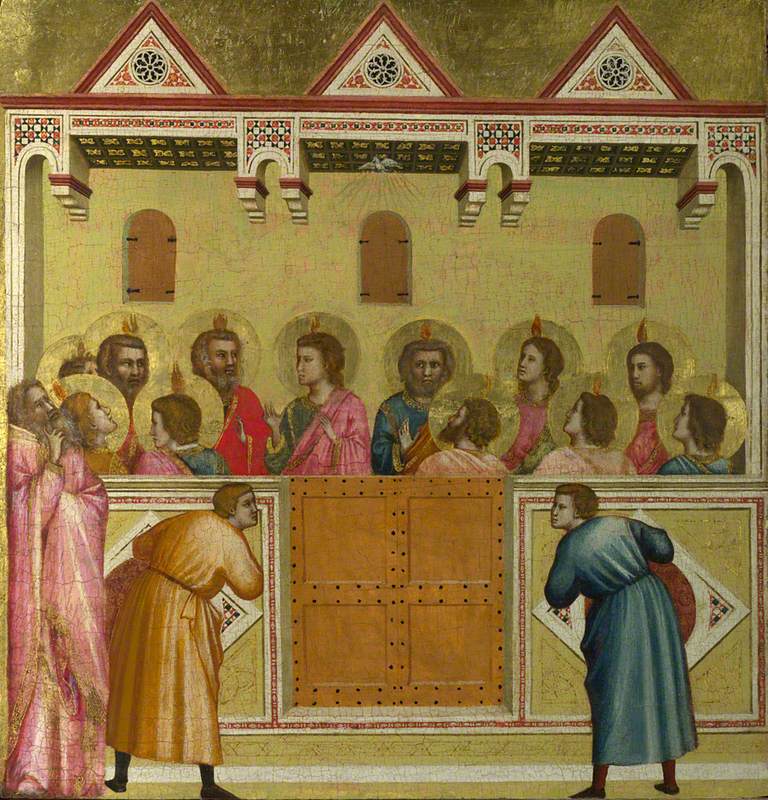

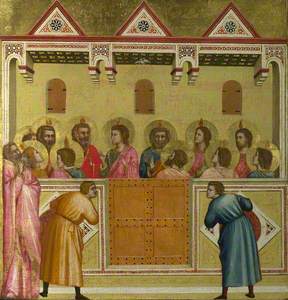

What do we mean by 'ghost'? The word was once commonly used to refer to the third part of the Christian Trinity – the Holy Ghost. This was often depicted in art as a dove, or tongues of fire, or rays.

That religious usage in English is largely now replaced with 'spirit' (from the Latin 'spiritus'), as the word 'ghost' has come to mean the disembodied manifestation of a deceased person (or animal).

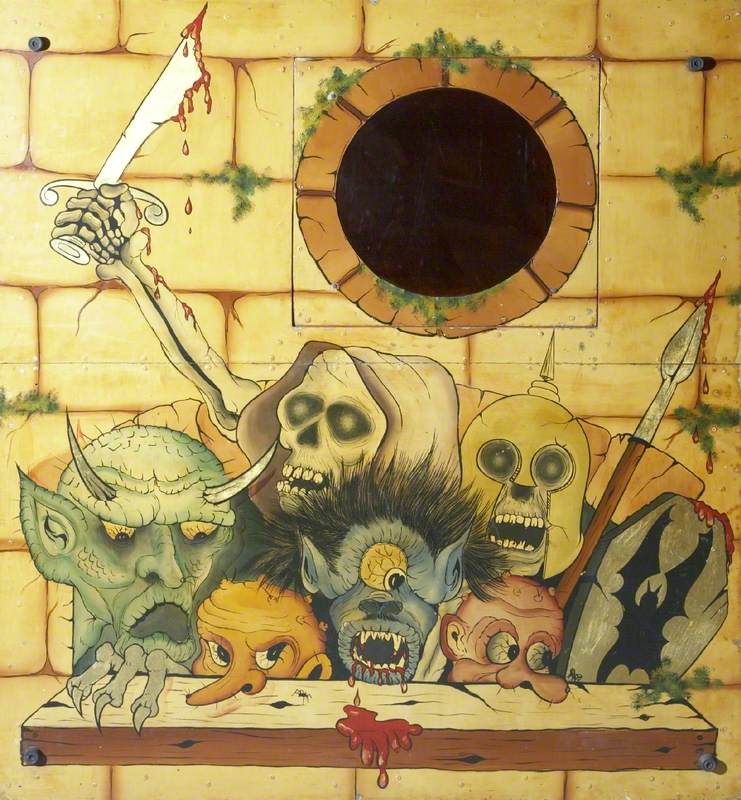

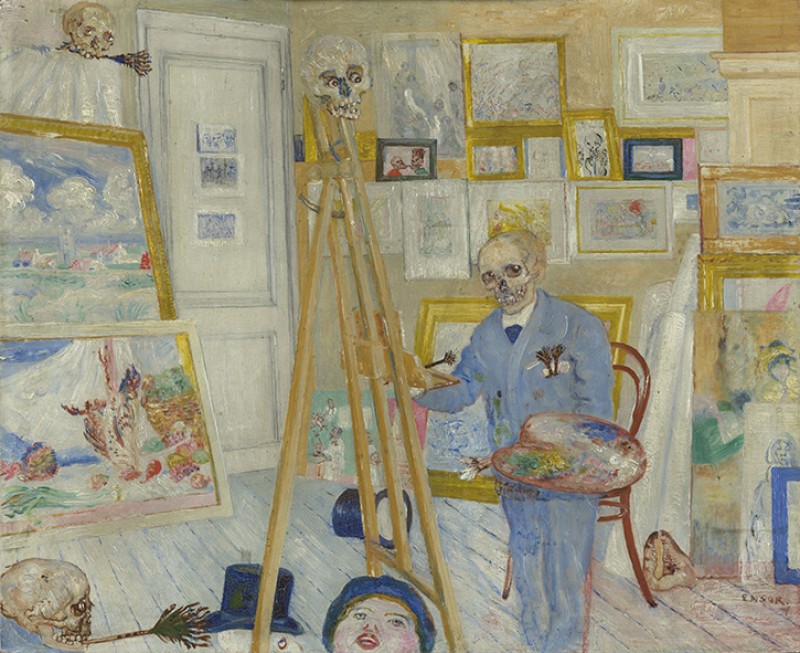

Over time, artists have rendered ghosts, spooks, spectres, ghouls, apparitions and wraiths in a variety of ways.

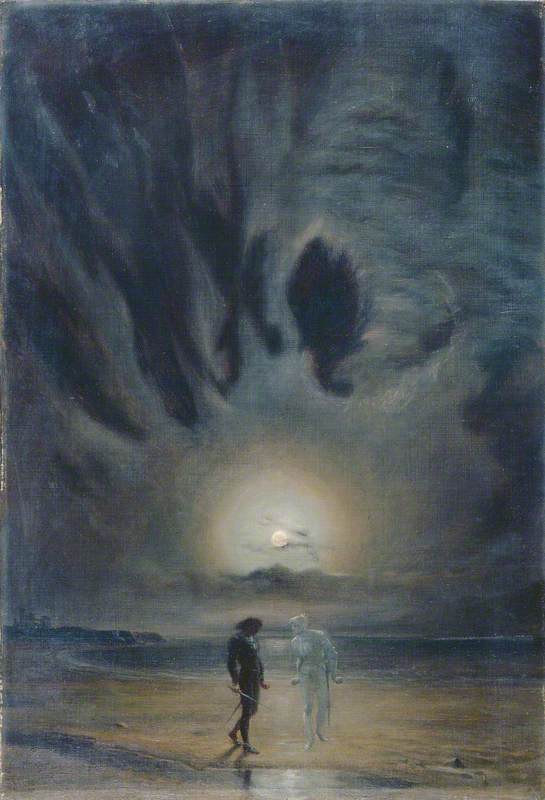

A famous example is the ghost of Hamlet's father (also called Hamlet).

John Henderson as Hamlet in the Ghost Scene of 'Hamlet'

1775

unknown artist

The character has been brought to life (well, not life...) on stage in different ways, and artists have captured that scene too – some faithfully rendering what was on stage, and others with a more cinematic approach.

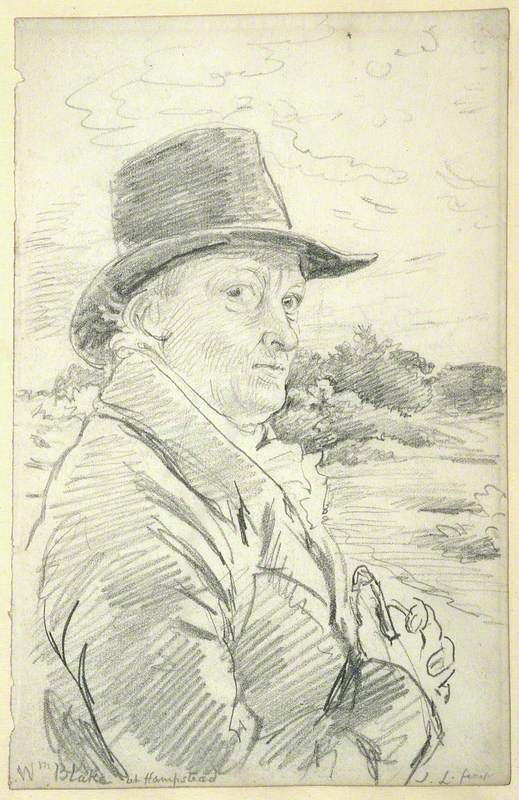

If you wanted a wildly original take on things in the Romantic period, you could always rely on the ever-quirky William Blake. His painting The Ghost of a Flea is just that – the literal ghost of a flea.

It is part of a series of 'Visionary Heads' commissioned by the watercolourist and astrologist John Varley (1778–1842). Blake and Varley would get together and conduct seances, and the flea apparently appeared to them at one of these sessions. Varley was unable to see the spirits conjured, so Blake drew them...

Ghosts also represented the ever-present spectre of disease in times gone by.

A Ghostly Skeleton Trying to Strangle a Sick Child; Representing Diphtheria

Richard Tennant Cooper (1885–1957)

From diphtheria to tuberculosis, the Wellcome Collection has a few notable examples.

The very real horrors of the First World War were responsible for a rise in sightings of the supernatural. Long-suffering troops, many of whom were under the stress and strain of shell shock and what we would today call PTSD, regularly reported seeing ghosts of former comrades killed in action.

Some of these sightings can be attributed to a fictional short story published in the Evening News in September 1914, in which English bowmen killed at the Battle of Agincourt (1415) rose up to defend their countrymen in the contemporary conflict.

Ghost stories told in literature have been perennially popular, and similarly artists have periodically taken it upon themselves to depict haunted places, often with a sense of Gothic foreboding.

Georg Emil Libert (1820–1908) was born in Copenhagen, and worked across southern Germany and Austria. This painting is a fine example of the Romantic imagery which developed in Northern Europe in the nineteenth century.

It shows a frozen river where three boys play and an austere (supposedly haunted) manor in the middle distance. Dated 1847, the work was made shortly after Libert went to Munich where he met a group of Romantic painters under the influence of Caspar David Friedrich (whose only work in the UK is a haunting winter landscape at The National Gallery).

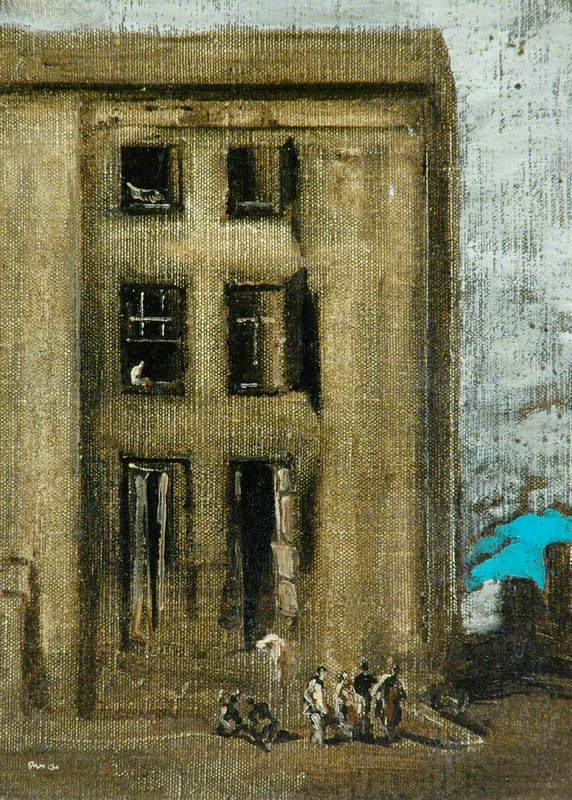

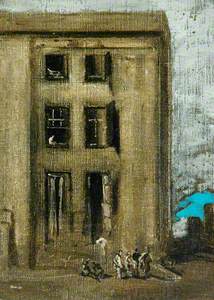

James Ferrier Pryde was a painter and designer, as well as being the brother-in-law of (the much more famous) artist William Nicholson. He is best known for dramatic and sinister architectural views, with figures dwarfed by their gloomy surroundings. The title of this work doesn't leave the interpretation to the viewer – it's a haunted house, so those figures in the windows may well be the ghosts about to haunt you.

Alfred Munnings created a vast body of work and the majority of his paintings were of horses and horseracing. It seems as if he dabbled in haunted things occasionally, however.

This painting was originally titled In the Room: A Problem Picture.

The Haunted Room, Painted at a Farmhouse on Exmoor

Alfred James Munnings (1878–1959)

When it was displayed at the Royal Academy in 1952 it caused quite a stir amongst the public and press as it was so unlike any other painting ever exhibited by Munnings. The artist stated that he just let the painting develop as the fancy took him – initially focusing on just the figure in the bed, shown in this study.

He later decided that the picture needed a ghost. When asked about the narrative he was rather vague: 'maybe' the man on the ground had run the ghost through in a duel.

The actual bed in the painting is real and was reputed to have had a sinister past, coming from Littlecote Hall, Wiltshire, where Wild Will Darrell murdered a baby and was convicted on evidence which included a piece of cloth from the bed.

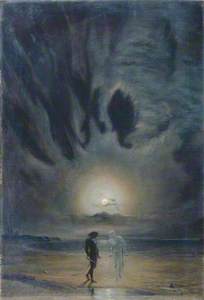

It wasn't Munnings' only foray into the supernatural. The subject for this painting may have been inspired by a poem written by Robert Burns.

Munnings described the composition in his autobiography as: 'a country couple, staring in the moonlight at a female phantom with outstretched arms, and a lovely head thrown back, appealing to the stars, her white robes trailing on the still water reflecting her luminous figure and the sickle moon.'

Carel Victor Morlais Weight (1908–1997), for many years professor of painting at the Royal College of Art in London, always said that he had a lonely childhood which was full of dreams of ghosts – that sense, of the supernatural in the everyday, is apparent in many of his paintings. However, his 1980 Ghost in Garden is a straightforward example of an artist literally painting a ghost.

There's no explanation as to why it's there, or what it represents, and perhaps that makes it all the more impactful – apparitions are unexplained phenomena and the painting reflects that.

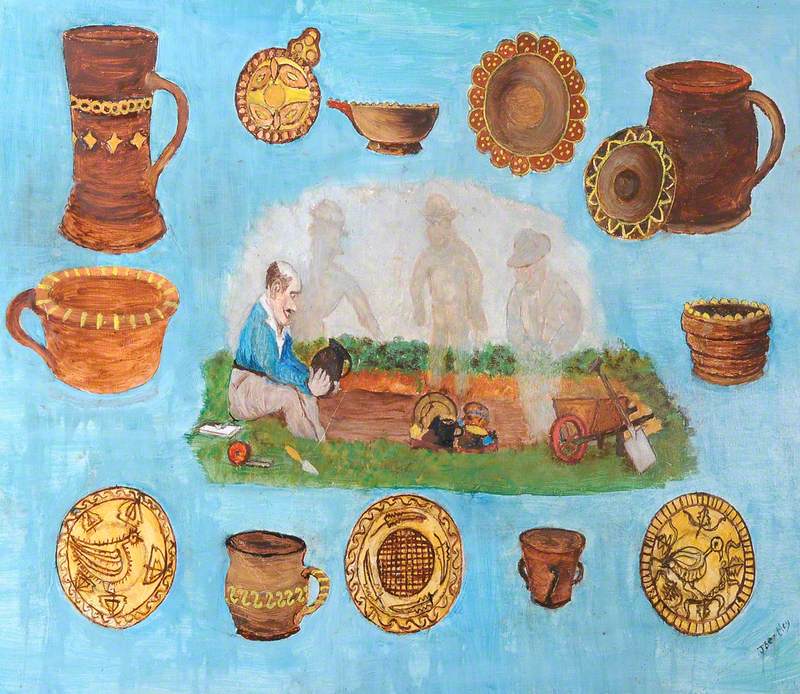

An unusual idea of the souls of the dead being all around us, this painting shows local archaeologist (and artist) James Bentley digging up late medieval and early post-medieval pots at Brookhill in Buckley, a town in Flintshire in North Wales.

Surrounding him is a group of ghosts of seemingly benevolent potters – the ones who made the pottery in the first place, long dead but still interested in what's happening to their works.

A truly unsettling image is this sculpture by Finnish artist Kim Simonsson, titled simply Ghost.

Made of glazed stoneware, the white skin and unseeing eyes of the creepy child evoke horror movies and the uncanny. As a quote on his own website from fellow artist Johan Sjöström says: 'His sculptures in glazed stoneware operate on both sides of the threshold of consciousness. These physical objects have a strangely timeless quality, as if they were quiet representatives of a detailed but unknown borderland.' I hope nobody's reading this just before bed.

Although in art spooks and spectres have been largely allegorical, this example of trick photography (a double exposure) shows that quite often it turns out to be just some guy messing about in a sheet!

A Spectre

(from an album of doppelgängers and spectres, early 1900s) early 1900s

unknown artist

And he would have gotten away with it if it weren't for us meddling art lovers...

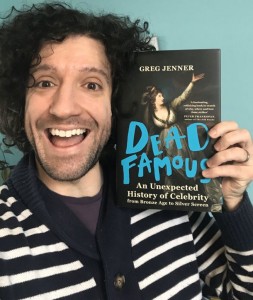

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK