'The key thing dividing great art from the gothick [sic],' wrote John Smith, in 1701, is 'the Justness, Nobleness, and Gracefulness of […] Expressions.' Smith was writing the dedication for his English translation of the Conference of Monsieur Le Brun, the celebrated yet austere chief painter to Louis XIV. In 1668, concerned at the apparent incompetence of young painters, Le Brun delivered a series of lectures to students at the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture on the proper representation of facial expressions. These were illustrated with 23 drawings depicting faces experiencing key emotions such as hate, despair, laughter, fear and astonishment.

Charles Le Brun died in 1690, but his lectures, transcribed and published in 1689, were widely translated (including by Smith) and published throughout Europe. As a result, they became a key text in the development of artists' ideas about facial expression and characterisation throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

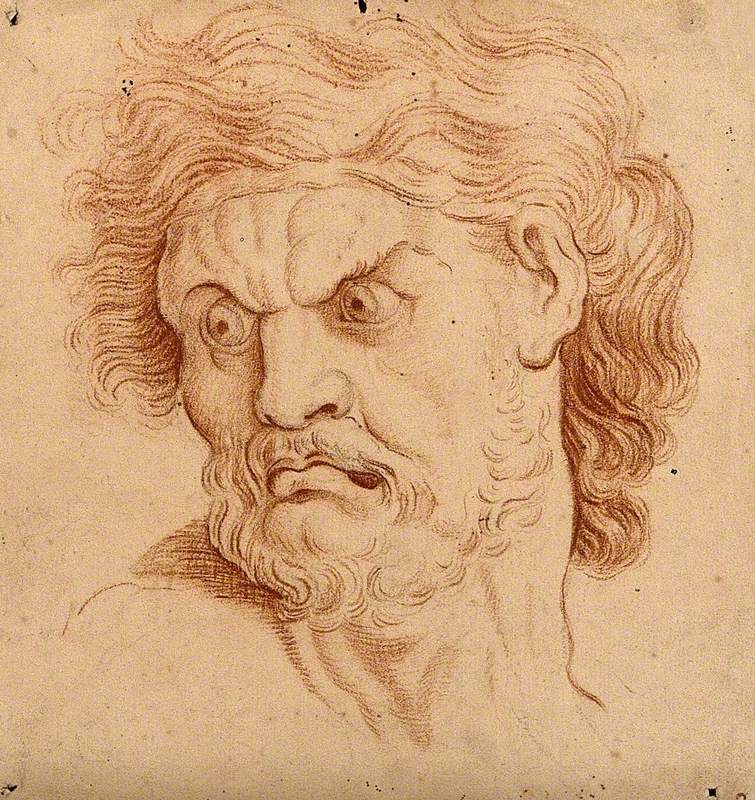

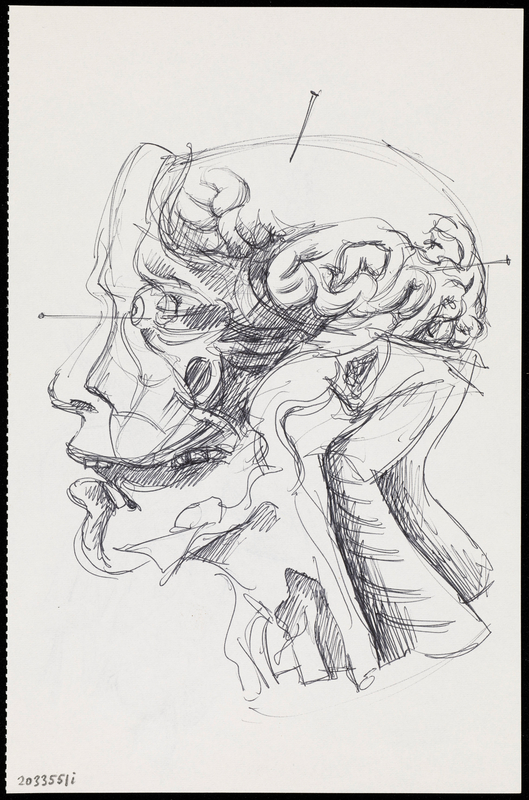

Though Le Brun's project sought primarily to 'direct our young Painters in the right way,' it was also insistently scientific, drawing on the work of the philosopher René Descartes to better understand what causes expressions in the first place. Le Brun believed in the principle that 'whatsoever causes Passion in the Soul, makes some Action in the Body.' Through detailed experimentation, including dissecting the faces of animals, Le Brun concluded that the key to everything lay in the eyebrows. Under the influence of what he called 'concupiscible' passions – chiefly love and hatred, joy, sorrow and pain – they moved up. 'Irascible' passions – such as hope, despair, confidence and fear – caused them to descend. Le Brun's sample drawing of 'Anger,' an irascible passion, illustrated its effects. The subject developed 'red and inflamed eyes.' 'He will seem to grind his teeth […] The veins of the forehead, temples and neck will be swollen and taut.'

Like the text, Le Brun's drawing (which was engraved and printed in 1727), shows a man; others in the series (such as 'Acute Pain') are ambiguously androgynous. Indeed, Le Brun generally avoids giving his figures any narrative context. Nothing explains what has brought this man to such a pitch of rage. He wears no clothes that we can see, does not appear particularly young or old, and rages against a blank background. Even his hair, which might appear to be ruffled by the wind, is identified in the text as 'bristling' – the result not of atmospheric conditions, but of the 'abundance of blood' brought about by strong emotion.

This helps underline Le Brun's scientific credentials: rather than a depiction of a person or an event, these drawings are prototypes, presented for artists to study, and copy – something their status as drawings, with all the standard academic connotations of study and preparation, makes particularly clear. Le Brun hoped the rigour of his approach would help elevate the popular and critical status of painters of fine art in contrast to journeymen sign-painters and other artisans. By 'painting', Le Brun meant specifically 'history painting': large-scale works illustrating notable events from history and poetry. This genre was traditionally at the top of the hierarchy of painting in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

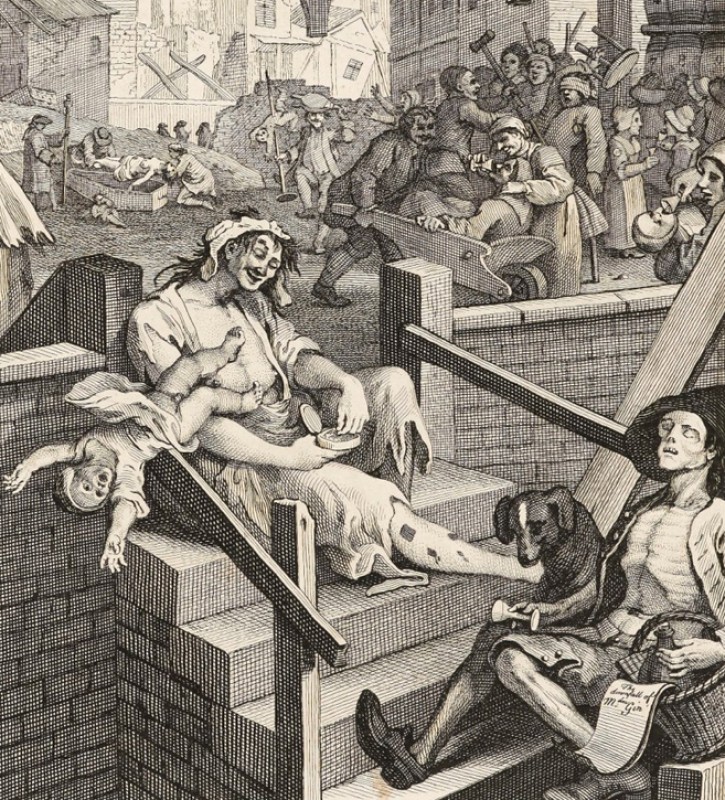

The British painter and printmaker William Hogarth probably read Le Brun in Smith's translation; by 1753, he was referring to 'Le Brun's passions of the mind' as 'the common drawing-book for the use of learners.' Hogarth's friend, the actor David Garrick, liked to run through imitations of the illustrations at dinner parties. Yet despite its cultural dominance, Le Brun's project had obvious shortcomings. Chiefly, since facial expressions are movements of the features, they are inherently transient and difficult to reduce to a rigid prototype, something Hogarth clearly wrestled with in his own work.

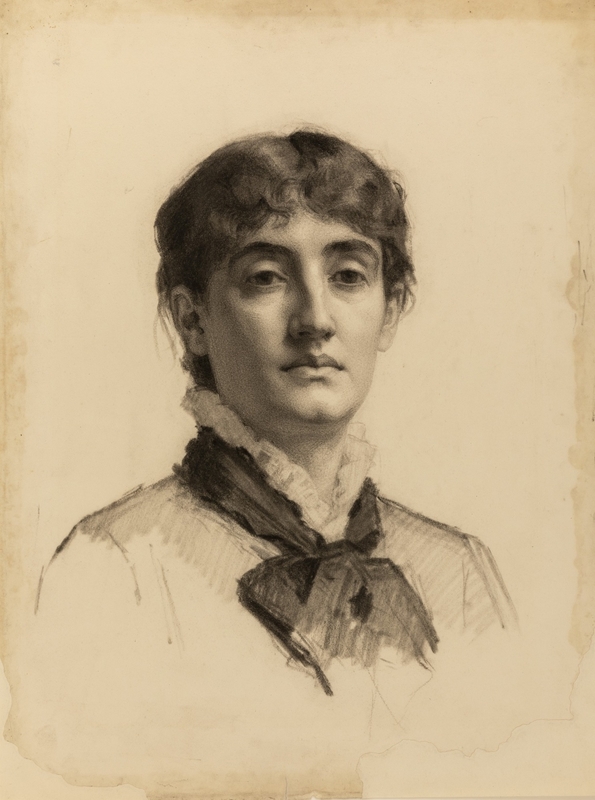

Shortly after the decisive defeat of the 1745 Jacobite rising, Hogarth travelled to St Albans to draw a portrait of the captured rebel Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat. Lovat was notorious as a kidnapper and rapist as well as a Jacobite and would become the last man in England to be beheaded.

Simon Fraser (c.1667–1747), 11th Lord Lovat

1746

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

Hogarth's portrait shows his familiarity with Le Brun: Lovat's expression is carefully delineated, with arched eyebrows (furrowed in the middle, in line with the irascible passions). At the same time, there is a naturalism about the figure's piercing stare and untrustworthy leer, resulting in an expression that is difficult to precisely define. This is a strikingly effective method of representing a man known as a turncoat and double-dealer, whose pronouncements, whether visual or verbal, should not be trusted. At the same time, the mobility of the face is underlined by the sense that we have caught Lovat mid-reminiscence: he is counting off the highland clans that fought for him on his fingers.

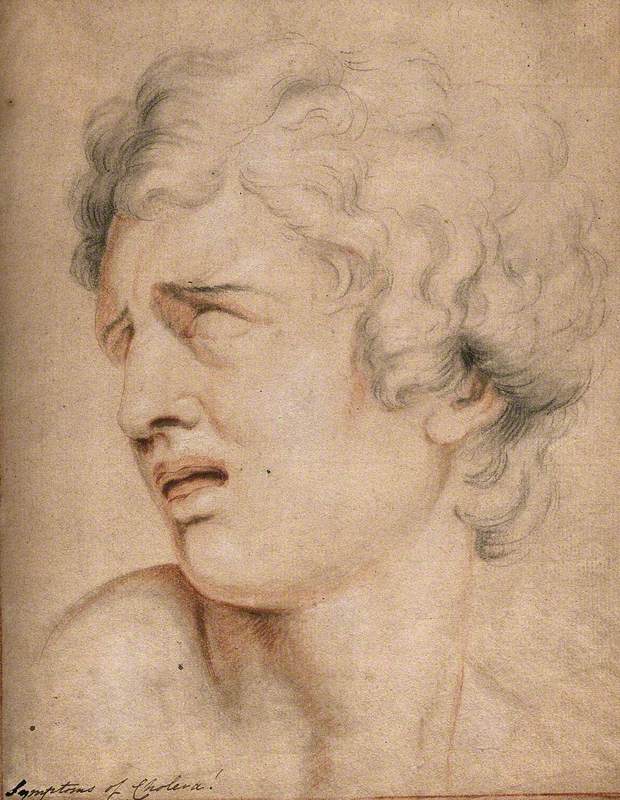

Hogarth's drawing was later issued as a shilling print and became an instant bestseller, reflecting a growing popular interest in images of criminals and rogues. Hogarth's customers were certainly buying into the latest sensational news, but they were also presumably hoping to see, in a development of Le Brun's theorising, how far the details of deeds could be traced in the face. Over the course of the 1770s, this idea would take on a new resonance through the work of the Swiss minister and physiognomist Johann Caspar Lavater, whose work – particularly his Essays on Physiognomy (1789) – was widely reprinted, summarised, parodied and discussed. Lavater maintained that there was a 'correspondence between the external and internal man, the visible superficies and the invisible contents,' and that both could (and should) be organised, categorised and scientifically studied.

Lavater's theories were illustrated with systematised faces and diagrams like those that had accompanied Le Brun. Nevertheless, his thesis was in many ways the opposite. While Le Brun was interested in the external manifestation of transient emotion (specifically manifested in the eyebrows, as set in motion by the muscles), Lavater was preoccupied with the skull, dismissing the flesh that covered it as irrelevant, and believing that a person's fundamental way of thinking was analogous to (and indeed partially formed by) the shape of their body. While Le Brun had suggested that facial expression could be systematised according to a set of biological principles and prototypes, flattening difference to arrive at a universally applicable ur-expression, Lavater was interested in what made an individual distinct. However, he proposed to judge this by his new system, which focused less on the movement of the passions through the body and more on comparing and contrasting angles and measurements. This approach would ultimately make Lavater essential to the development of scientific racism and the construction of race.

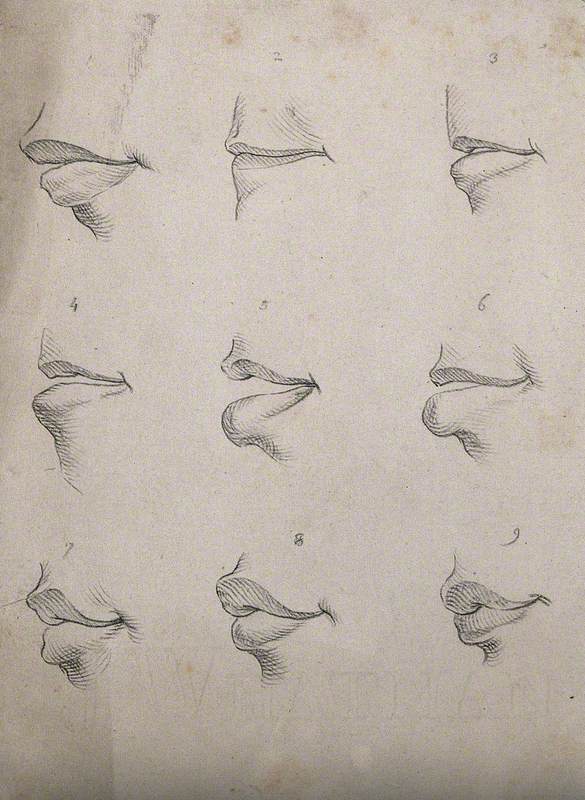

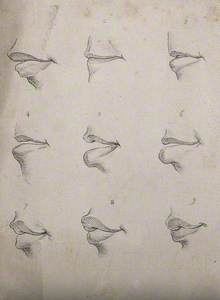

Lavater's Essays were translated into English by Henry Hunter in a lavish edition that sold for 30 guineas a set. The illustrations were provided in the main by Thomas Holloway. They included both diagrammatic images designed to teach comparison between different types of features (such as the plate for 'Nine Mouths'), and reproductions of notable physiognomies from art history – focusing on Anthony Van Dyck, Poussin and Raphael. Painting and physiognomy, therefore, continued to be closely entwined, though this time 'great' art was the example, rather than the aim. 'When I wish to fill my mind with admiration at the perfection of the works of God,' Lavater concluded, in a paragraph published beside a copy of Raphael's self-portrait, 'I have only to recollect the form of Raphael.'

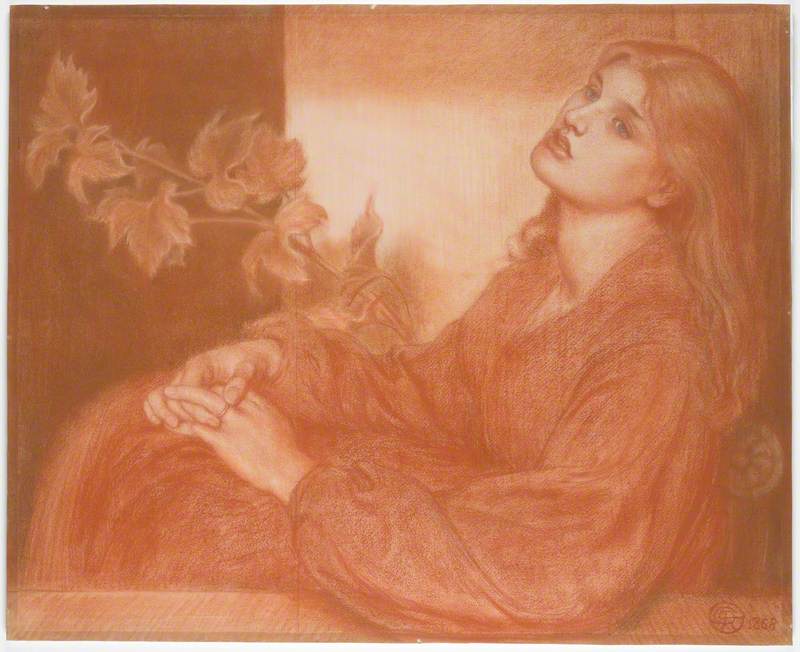

However, Lavater also had important connections with contemporary artists. Both Henry Fuseli and William Blake illustrated his work, and both incorporated Lavater's ideas into their own. In the autumn of 1819, Blake began working with the eccentric landscape artist and astrologer John Varley, creating a series of drawings now known as the 'Visionary Heads'. These were partially published as illustrations to Varley's 1828 Treatise on Zodiacal Physiognomy.

As recounted by Varley, the two men sat up all night while Blake, apparently in a trance, drew portraits of 'those whom I most desired to see.' Subjects included the poet Pindar – his face, as Varley described it, possessed by 'poetic fervour' – and, on the same sheet, an undistinguished 'courtesan' named Lais who (according to Varley) 'stept in' [sic] while Blake was drawing someone else, in an act of visionary queue-jumping ('he was obliged to paint her to get her away').

Visionary Heads (Pindar and Lais)

1820

William Blake (1757–1827)

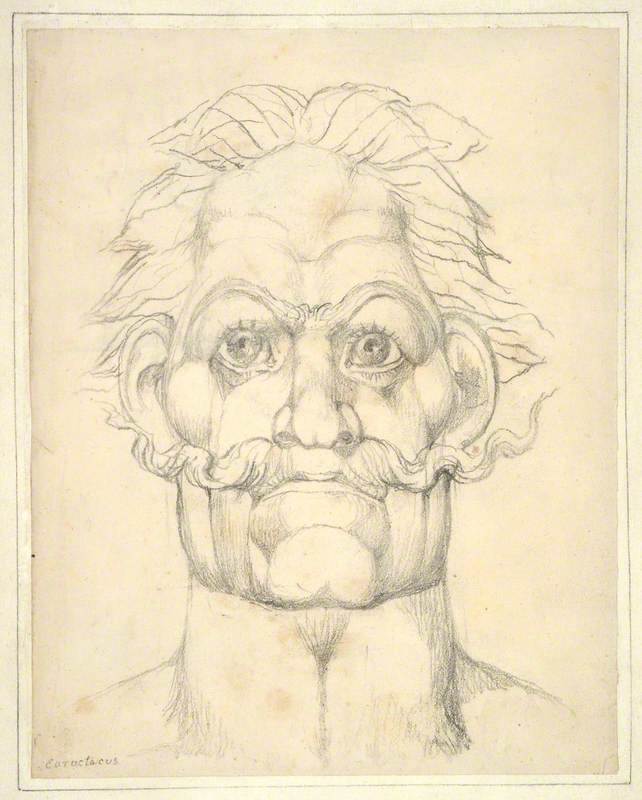

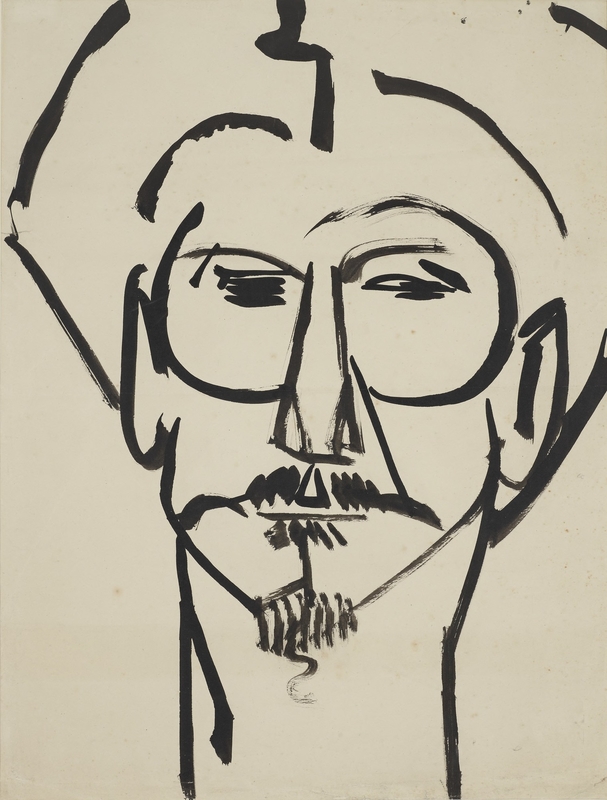

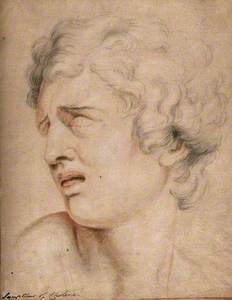

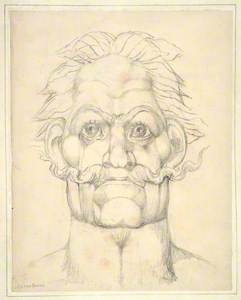

In general, however, the visionary sitters were either notable figures from history with strongly marked destinies (Owen Glendower, the Earl of Warwick) or personally anonymous people who had an impact on history ('The Man Who Built the Pyramids'). There was also a group of famous criminals. However, one of the most powerful portraits is Blake's drawing of King Caractacus, the British king who resisted the Roman invasion.

This is unlike most conventional portraits of the period. The king is presented fully face on, does not meet the viewer's eye, and (unlike Hogarth's portrait of Lovat) has no contextual mise-en-scene. Yet in contrast to the similarly free-floating heads of Le Brun, his face is almost studiously blank – expressionless – so the famous strength of his character is instead suggested by clearly delineated musculature. The drawing's scientific precision belies its imagined origin. Ultimately, however, this is an irony inherent to any attempt to systematise the expressive potential of the human face – which, as many of these writers and artists found, is not so easy to pin down.

Kirsten Tambling, writer and academic

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

G. E. Bentley, The Stranger from Paradise: A Biography of William Blake, Yale University Press, 2001

John Graham, 'Lavater's "Physiognomy" in England', Journal of the History of Ideas, 22:4, 1961, pp. 561–572

Johan Caspar Lavater, translated by Thomas Holcroft, Essays on Physiognomy: Designed to Promote the Knowledge and the Love of Mankind, William Tegg & Co, 1848

Charles Le Brun, translated by John Smith, The Conference of Monsieur Le Brun Cheif Painter to the French King, Chancellor and Director of the Academy of Painting and Sculpture; Upon Expressions, General and Particular, Translated from the French and Adorned with 43 Copper-Plates, printed for John Smith, 1701

Jennifer Montagu, The Expression of the Passions: The Origin and Influence of Charles Le Brun's Conférence sur l'expression générale et particulière, Yale University Press, 1994