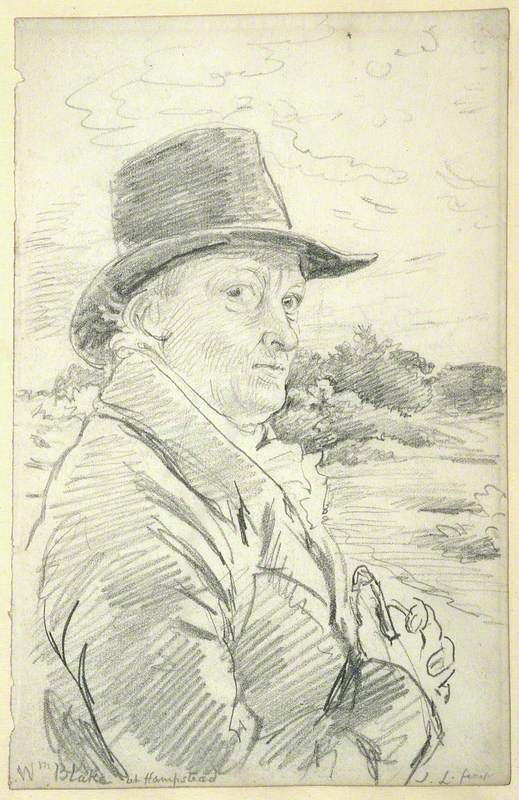

William Blake was a visionary artist and poet who expressed his ideas in words and images, which he combined in his rare, hand-coloured and hand-printed books.

Poems such as The Chimney Sweeper and The Tyger are among his best-loved and from his poem Milton are the words to Jerusalem, set to music by Hubert Parry. Blake's art allies the crisp outlines and idealism of the neoclassical style with a personal romantic vision.

Blake was born in Soho, London, in 1757, the son of a hosier. From an early age he saw religious visions. His artistic talents led his father to send him to Henry Pars' drawing school at the age of 10, where he learnt to copy from prints and plaster casts, and in 1772 he was apprenticed to the engraver James Basire.

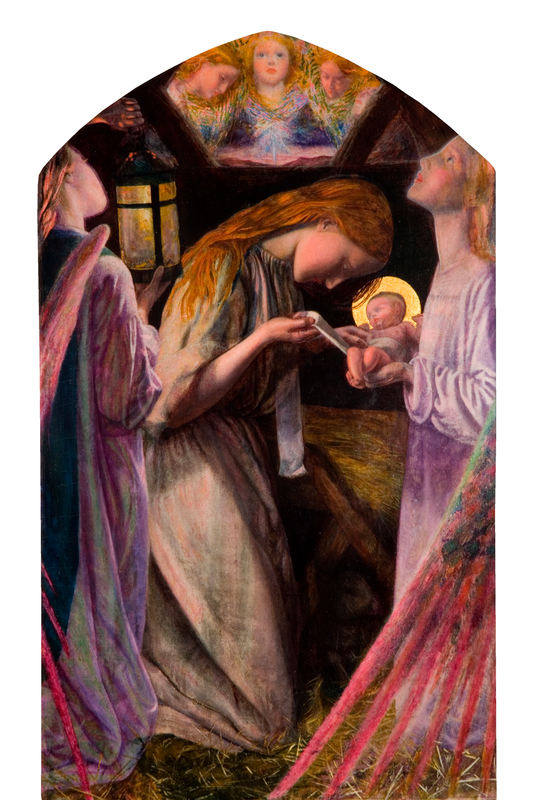

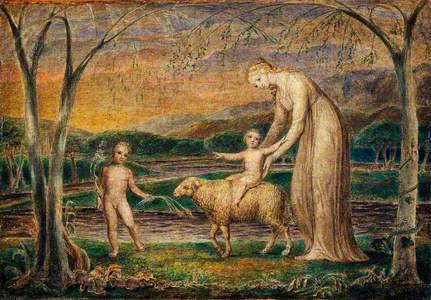

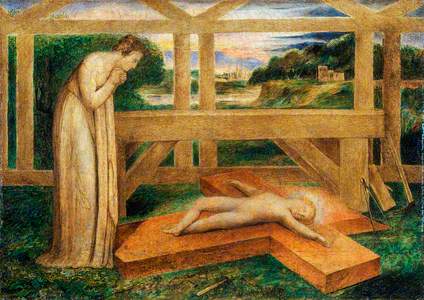

Our Lady with the Infant Jesus Riding on a Lamb with Saint John

1800

William Blake (1757–1827)

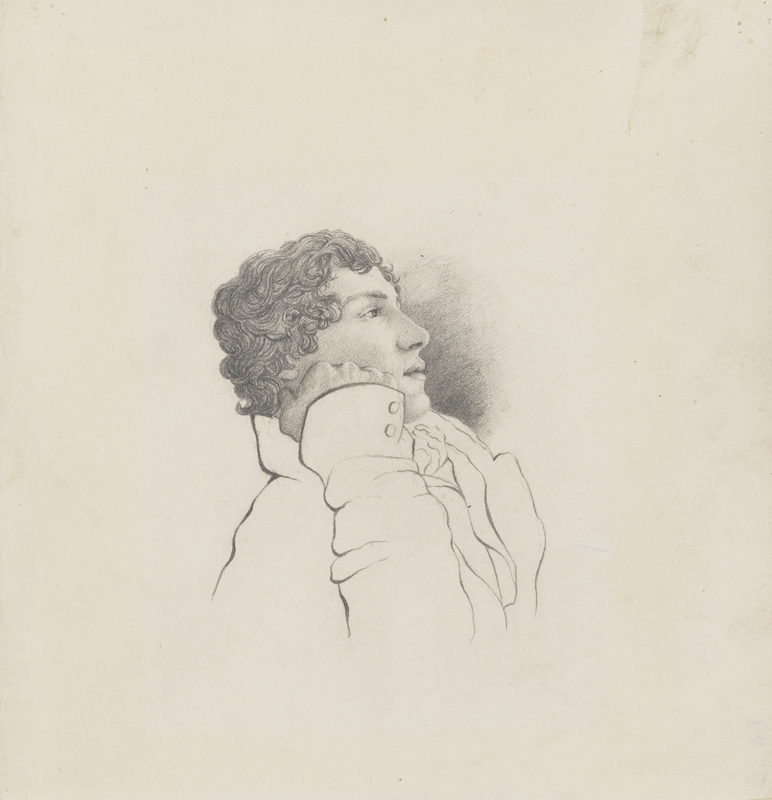

Blake entered the Royal Academy schools in 1779, but he disliked life drawing, preferring classical sculptures and Greek vase paintings. There he befriended some of the leaders of the neoclassical movement, such as John Flaxman and Thomas Stothard.

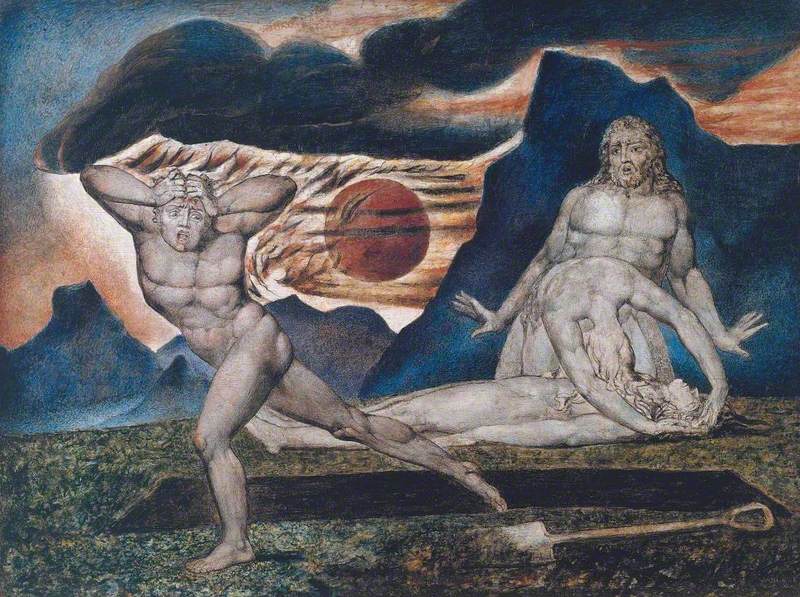

Blake's personal artistic vision clashed with his work as a reproductive engraver and he was beginning to achieve a reputation as poet – Poetical Sketches was published in 1783. In the 1780s he also exhibited several apocalyptic subjects at the Royal Academy. Blake shared the artistic establishment's view that art should address great historical, religious and philosophical subjects. A continuing theme of his work was the conflict between rulers and their people, a radicalism that coincided with the period of the French Revolution.

The death of Blake's father allowed him time to develop a printing technique that enabled him to combine his visionary texts and images on one printing plate. The first successful work of this kind was the Songs of Innocence (1789), to which was later added Songs of Experience (1794).

William Blake was born #onthisday in 1757. Here are the title pages for Songs of Innocence and of Experience pic.twitter.com/LWnLxTwAzF

— British Museum (@britishmuseum) November 28, 2013

Songs of Innocence was followed by The Book of Thel, one of Blake's works of prophecy, and in 1790 by The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, an attack on the Christian mystic Swedenborg and an account of Blake's own spiritual and artistic struggles.

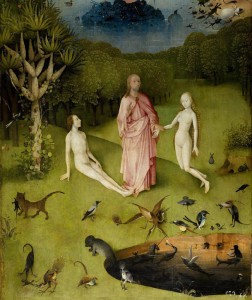

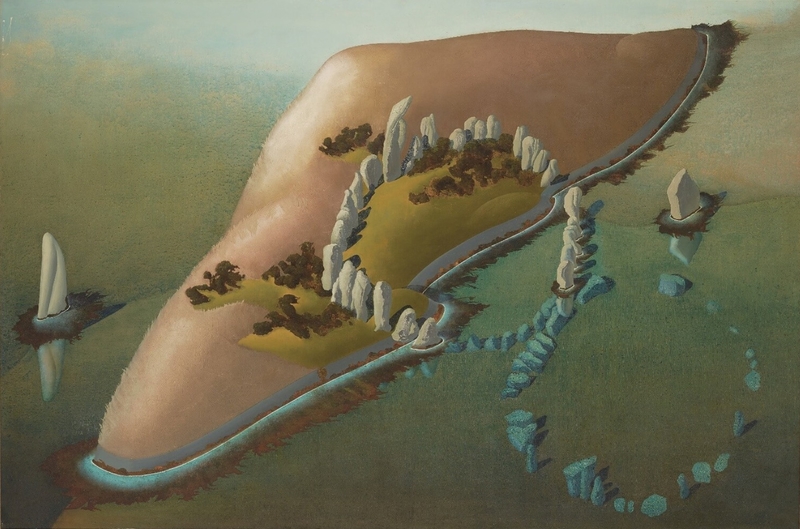

Visions of the Daughters of Albion, America and Europe, three further books of prophecy from 1793 to 1794, were based on Blake's views that the French and American Revolutions were the precursor of the Final Judgement of mankind and that America was the embodiment of political and spiritual liberty. Further small books, Los, Urizen, and Ahania, retellings of the Old Testament, were full of strong images, and 12 large individual prints, with some of his most famous images such as Newton, followed in the mid-1790s. But all these books were sold in very small numbers, copies of each edition differently compiled and coloured.

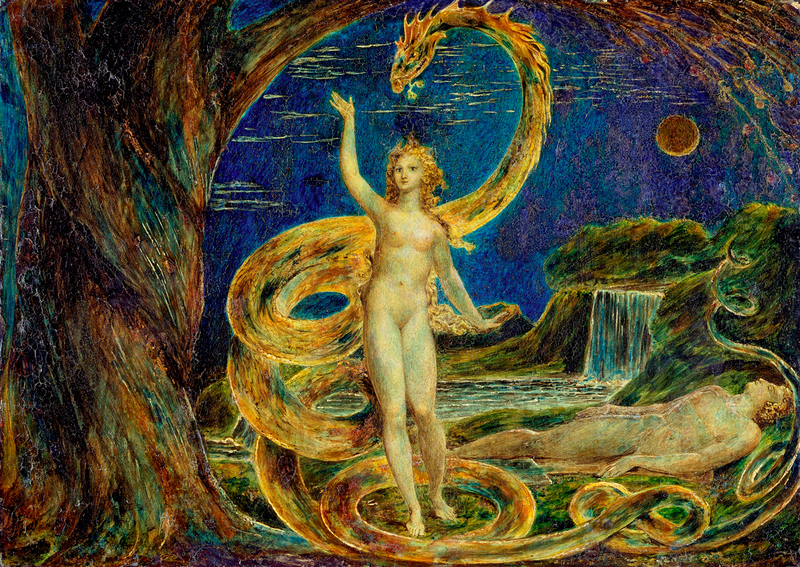

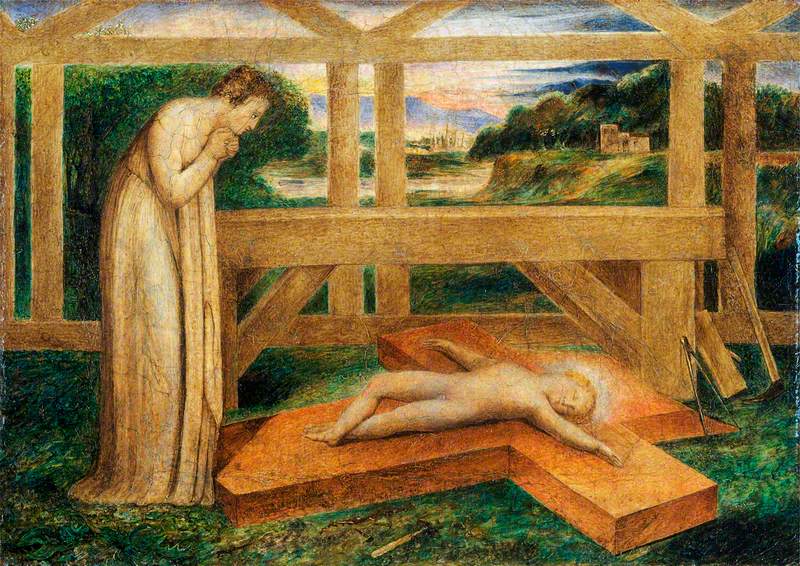

Blake had more success with independent works, such as several series of tempera paintings and watercolours of biblical subjects for his most important patron Thomas Butts (such as The Body of Christ Borne to the Tomb and The Christ Child Asleep on the Cross). Blake's livelihood relied on patrons but some, such as the well-meaning William Hayley, were more concerned with his welfare than his art.

In 1809 Blake arranged an exhibition centred on his large painting of The Canterbury Pilgrims. The exhibition's Descriptive Catalogue contained a defence of his art, torn between classical ideals, interpretations of biblical prophecies and his own visions. But most saw in the exhibition and catalogue only 'the wild effusions of a distempered brain'. Even in a period when personal experience and grand themes were increasingly highly valued, Blake was considered particularly eccentric and unworldly.

At the time of the exhibition, Blake was living in dire poverty, supported only by Thomas Butts, and was also working on two final prophetic books, Milton and Jerusalem. He received additional commissions from Butts and the Reverend Joseph Thomas for illustrations to Milton's poems (Satan Calling Up His Legions is from Milton), and for The Book of Job (1825–1826).

Satan Calling Up His Legions

(from John Milton's 'Paradise Lost') c.1805–1809

William Blake (1757–1827)

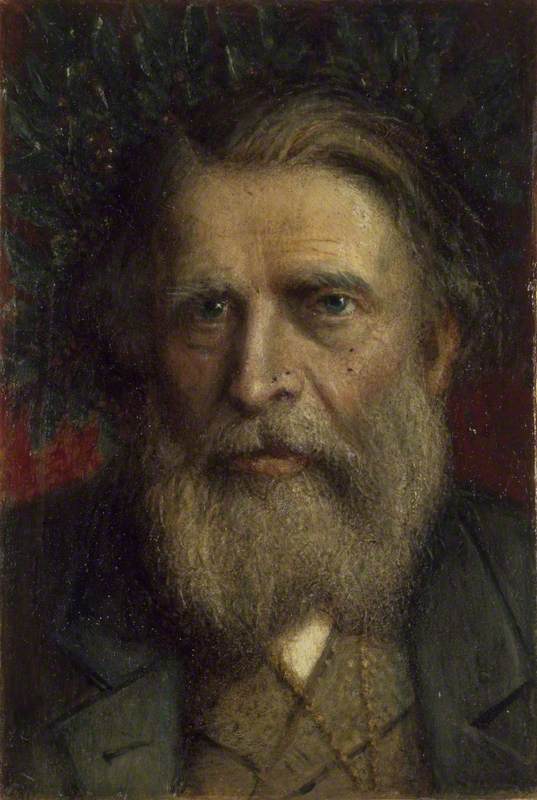

100 unfinished watercolours for Dante's Divine Comedy (including Ugolino and His Sons in Prison), begun with John Linnell's encouragement in 1824, show Blake at a new peak of creativity.

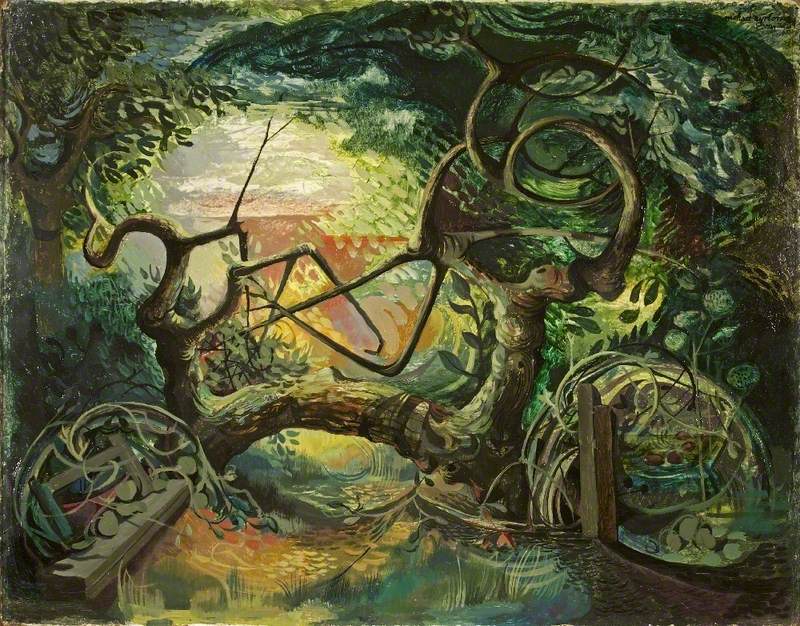

In Blake's last decade he began to be recognised by a new generation of young Romantic artists. The landscape painters John Linnell, Samuel Palmer and Edward Calvert were particularly supportive, despite Blake's unorthodox Christianity and his distrust of the natural world. But by then his earlier revolutionary and visionary fervour seems to have largely died down and in 1822 he even accepted a gratuity from the Royal Academy. He died in 1827.

Andrew Greg, National Inventory Research Project, University of Glasgow