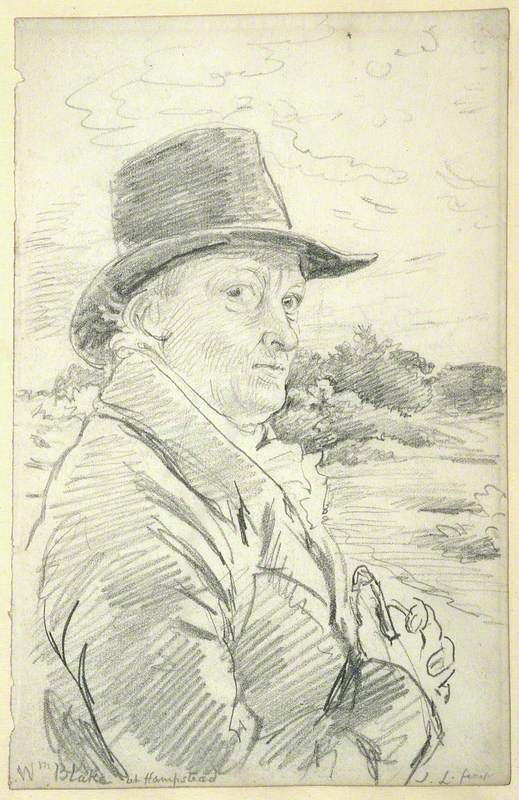

Imagine the man who teaches English to children who only like maths. Imagine the man who wishes someone cared about the arts. Imagine the man who teaches Paradise Lost to atheist sixth-formers. This is the man who wears William Blake Doc Martens.

Wear Blake’s iconic artwork on your feet courtesy of our collab with Tate Britain.

— Dr. Martens (@drmartens) November 8, 2017

EU https://t.co/I0llLwLmWI

US https://t.co/aONifluY8A pic.twitter.com/vPraONGfCc

Indeed, my first experience of this work four years ago was through the medium of shoe leather as Satan's body curved round my English teacher's foot. There is perhaps a cruel irony in this as the very industrialisation and mass production that Blake and his fellow Romantics railed against allowed me to discover their work.

Blake was a big believer in the crossover of the arts, being both a visual artist and a poet, and so it is apt that it was an English teacher who introduced me to it. This work is a representation of a story in the Book of Job from the Old Testament, discussing the nature and cause of evil. Blake's visual and written works were often intertwined and so it feels only right to discuss this work in the context of his writing.

Britain's favourite hymn, Jerusalem, is a Blake poem set to music in which 'the Countenance Divine' is contrasted with 'dark satanic mills'. In this painting however, God is not present. Rather, Satan in the foreground takes up most of the space of the work, seemingly stooping slightly in his torturing of Job to even fit within the bounds of the panel. Satan is clearly presented as incredibly powerful, standing atop the man he is smiting; humanity, whilst also in the foreground, lies static or curled up tightly compared to the spread dynamism created by the diagonals of Satan's arms and wings. Satan is all-powerful compared to humanity.

However, Blake symbolically associates Satan with human activity. The black smoke behind his wings hints at those 'mills' and the industrialisation of the economy in the nineteenth century. There is no 'green and pleasant land' – rather than the grand, soft greens, blues, and yellows of Romantic art as used by Turner and Constable, Blake here depicts an unnatural discolouration of the natural world in black water and blue vegetation. The perversion of nature is further highlighted through the sharp edges of the Sun's rays in the same manner as Satan's wings are formed. Moreover, the image itself is presented on a mahogany panel, physicalising the presented destruction of nature.

Blake's bleak depiction of the state of the world perhaps belongs even better in a world of rapid anthropogenic climate change than his own – I can see Blake championing Extinction Rebellion or supporting Greta Thunberg and continuing his radical activism through art. The Book of Job depicts Job's stoic belief in God to make his life right again and so Blake, through his use of the Biblical story, is hinting that this is not the end; there is a way out of environmental disaster. His poem reminds us to 'not cease from mental fight', just as Job does not. Fighting for a better world is possible despite the seeming impossibility of change for the better.

The Sun is only half visible over the horizon line and so this is merely a liminal time. The viewer is invited to remember that they are a defender of Creation and on the side of God. Whilst Doc Martens were not the medium Blake had in mind, it surely is better to use emissions to advocate for fewer in future, and besides, Blake would be pleased with the success of this image that he never had when he was alive.

George Rowe, second-place winner of Write on Art 2022, Years 12/13

Further reading

William Blake, Jerusalem, Poetry Foundation, 1810

Martin Myrone, William Blake, Tate Publishing, 2019

Andrew Sanders, The Short Oxford History of English Literature (Third Edition), Oxford University Press, 2004

Tate's description of the painting, 2010

Victoria and Albert Museum, 'The Romantic Tradition in British Painting 1800–1950', 2002 (abridged from the touring exhibition catalogue by Mark Evans)