In 1760 the painter Benjamin West visited Rome only to complain that Italian artists 'talked of nothing, looked at nothing but the works of Pompeo Batoni'.

It wasn't only the Italians who celebrated the painter and draughtsman Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787). An acclaimed painter of altarpieces, religious and classical subjects, Batoni eventually became a highly sought-after portraitist amongst British aristocrats in the 1740s and 1750s.

Batoni was so favoured by the British, that out of the 225 known individual sitters he painted, 175 were British. The artist's success as a 'Grand Tour' portraitist relied not only on his popularity by word of mouth, but his ability to enhance the social status of his wealthy subjects.

But before we decode his portraits, what was a Grand Tour?

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Grand Tour was a rite of passage for the young male members of the British landed gentry, usually after completing their university studies. To travel across Europe signified affluence, sophistication and maturity. Crucially, it gave these young gentlemen a cultural education and a formal introduction to classical antiquity. The ultimate pilgrimage was to Italy and the cities of Venice, Florence, Naples, and most importantly Rome, where Batoni lived.

Batoni capitalised on the high numbers of wealthy, young individuals travelling through Italy. Although he was not the inventor of the 'Grand Tour' portrait – sixteenth-century artists like Maeten van Heemskerck had created a tradition of the 'Grand Tourist' portrait among Roman ruins – Batoni did perfect the genre. His commissions would travel from Rome to Britain, where they would be admired and read through specific iconographical details.

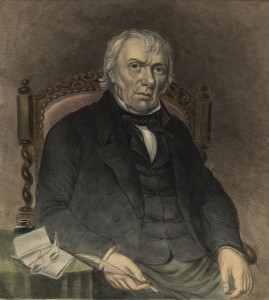

Batoni was the preferred portraitist, in part because he knew how to flatter his sitters. For example, it has been noted that Batoni greatly enhanced the physiognomy of Frederick North, who later served as Prime Minister from 1770 to 1782.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford 1753–1756

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonHistory has remembered Lord North for losing the American colonies, but also for his infamous unattractiveness. In this portrait, Batoni portrayed North as a man of affairs, as he pauses for thought while he writes a letter.

Clothing and posture

Besides capturing an excellent likeness, Batoni also had a reputation for understanding the changing fashions of eighteenth-century society.

Here, James Caulfield, 1st Earl of Charlemont, leans casually against a classical pillar in expensive and refined fabrics loosely tied together. The slightly dishevelled clothing and the sitter's nonchalant pose contribute to a sense of informality and familiarity with the subject.

A wealthy unmarried aristocrat, Caulfield spent nine years on his Grand Tour, travelling through Italy and Greece until he eventually ended up in Egypt.

Batoni often depicted his affluent sitters wearing red-heeled shoes. A sign of nobility and distinction, the red-heel shoe originated in France in the seventeenth century, at the Château of Versailles where Louis XIV wore the red heel as a symbol of power and importance. In 1673, Louis issued an edict declaring that only members of the nobility could wear his signature red-heeled shoe.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

John Ker (1740–1804), 3rd Duke of Roxburghe, Bibliophile 1761

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

National Galleries of ScotlandThe subject in this portrait is John Ker, the 3rd Duke of Roxburghe who had adopted the French fashion, which by that time had become popular among British aristocrats.

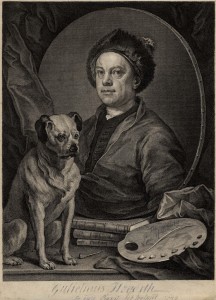

Canine companions

Many of Batoni's Grand Tour portraits also feature dogs, typically small spaniels or greyhounds.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Sir Robert Davers (1729–1763), 5th Bt, Aged 21 1756

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

National Trust, IckworthThis is because young gentleman would often bring their canine companions with them on the Grand Tour, alongside their coaches, horses, tutors and servants.

The inclusion of the small dog was also strategic, as it reinforced the good impression and affable nature of the subject.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Benjamin Lethieullier (1728/1729–1797), MP, with Two Wild Boar Spears 1752

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

National Trust, UpparkMore broadly, the presence of dogs in historical portraiture has been used to symbolise loyalty and fidelity. Batoni's particular interest in dogs may have been in homage to the Dutch royal portraitist Anthony van Dyck, who often showed his subjects alongside their pet.

Male friendship

Batoni often painted groups of young gentleman, who would have been companions voyaging together across Europe. Batoni had the ability to capture the camaraderie between his affluent subjects.

Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesThis portrait of Sir Sampson Gideon encapsulates male bonding among wealthy young Englishmen. Gideon is depicted showing his friend a portrait miniature of a young woman. Quite possibly, the miniature represents his wife Maria, who he married in 1767 (one year before this painting was completed).

Image credit: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Everard Studley Miller Bequest, 1963 (source: Google Arts Project)

Sir Sampson Gideon

(and an unidentified companion), 1767, oil on canvas by Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

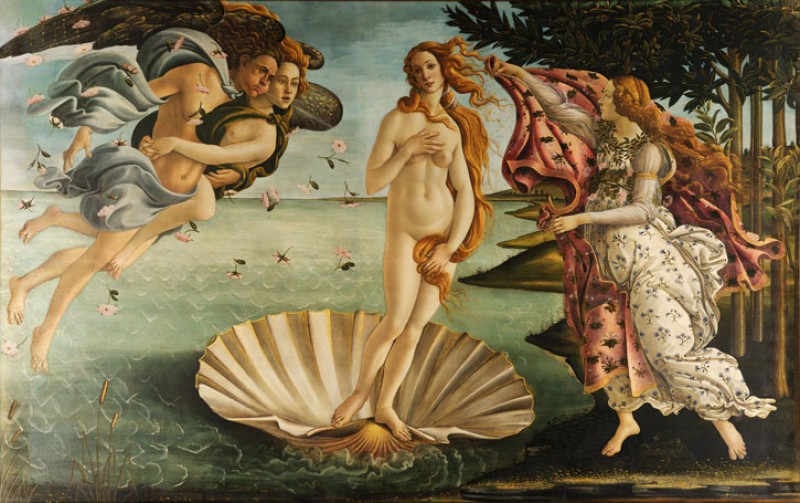

Classical backdrop

Importantly, Batoni's portraits represented his sitters within a classical tradition, against an idealised or arcadian backdrop, often featuring Roman architectural ruins, or statues of Greek or Roman mythological figures.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Thomas Peter Giffard (1735–1776) c.1765–1768

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787) (studio of)

National Trust, Coughton CourtQuite often his subjects were depicted next to sculptural busts of the Greek poet Homer, or the Roman goddess of wisdom, Minerva (looking much like her Greek counterpart, Athena). The symbol of Minerva helped to establish the sitter as a man of culture, knowledge and refinement.

This inclusion of classical sculpture not only mirrored the British fascination with antiquity during the flourishing of neoclassicism, but also Batoni's reputation as one of the finest copyists of ancient statues in Italy.

Symbols of cultivation

In 1776, the great English wit and writer of the first dictionary, Samuel Johnson, said, 'Sir, a man who has not been to Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see.'

Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1903

Portrait of a Young Man

c.1760–1765, oil on canvas by Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787)

Johnson was expressing the eighteenth-century belief that a visit to Italy was essential for a young nobleman's education. To illustrate this idea, Batoni's Grand Tour portraits often included props or symbols of learning and cultivation: books, musical instruments or globes.

In this portrait of Sir Gregory Page-Turner, he is (appropriately for his name) depicted next to a stack of books. A sword also hangs at his side, with the glint of the hilt visible. The Colosseum is visible in the background. Page-Turner was a wealthy aristocrat who eventually served as a Member of Parliament for 21 years.

In this 1772 painting of Robert Throckmorton, the sitter holds a print of the Pantheon, suggesting his interest and learning in classical architecture and Roman landmarks.

Another Batoni?

In the first episode of the 2019 series of BBC Four's Britain's Lost Masterpieces, Bendor Grosvenor and Emma Dabiri took a look at this portrait in Oxford University's Bodleian Library, which was initially described as the work of an unknown artist.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

George Oakley Aldrich (1721–1797) c.1750

Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787) (attributed to)

Bodleian LibrariesFollowing a closer inspection and extensive research, the work was indeed attributed to Batoni and the sitter joined the ranks of Britain's Grand Tourists painted by the great Italian portraitist.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK

Further reading

Robin Blake, 'In a benign and rational light Pompeo Batoni's pin-sharp portraiture brought the 18th-century artist international renown' in Financial Times (2008)

Stephen Lloyd, 'Pompeo Batoni didn't just paint aristocrats abroad' in Apollo (2016)

Edgar Peters Bowron and Peter Björn Kerber, Pompeo Batoni: Prince of Painters in Eighteenth-century Rome (2007)

You can find a selection of prints of works by Pompeo Batoni in the Art UK shop

![Sir Robert Davers, 5th Baronet (1729–1763) [aged 21]](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/h300/collection/NTIII/ICK/NTIII_ICK_851699-001.jpg)