Please note that this story was first published in 2016. In August 2019 The Times published an update (£) on tests undertaken on the picture at Haddo House.

Haddo House in Aberdeenshire is the most northerly stately home (as opposed to a castle) in Britain. Moscow is on the same latitude. In winter the days are short, and occasionally arctic. But that didn't stop the Earls of Aberdeen who lived there from wanting to create a house and landscape that took Italy, rather than Scotland, as its inspiration.

The house itself is built to a William Adam neo-Palladian design, and was begun in 1732. The landscape is now not what it was – fir trees have been planted in much of the park – but long vistas crowned with classical columns stand testament to George Gordon, 4th Earl of Aderdeen's deep interest in all things Roman.

The Italian theme continued inside the house too. Masterpieces by the likes of Veronese, Titian and Canaletto were amassed by the Gordon family during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Many of these were sold in the decades following (during what the current Marquess of Aberdeen tactfully describes as 'a period of fiscal naivety').

But many treasures remain. Perhaps because of the house's distant location, it appears not to have been as combed over by art historians as one might expect. When we began to research the collection for an episode of Britain's Lost Masterpieces, beginning as we always do through the Art UK website, it soon became clear that there were a number of exciting possibilities to investigate: a landscape described as 'attributed to Claude', but which had never been published or seen by Claude scholars before, as well as portraits by leading names described simply as 'British School'.

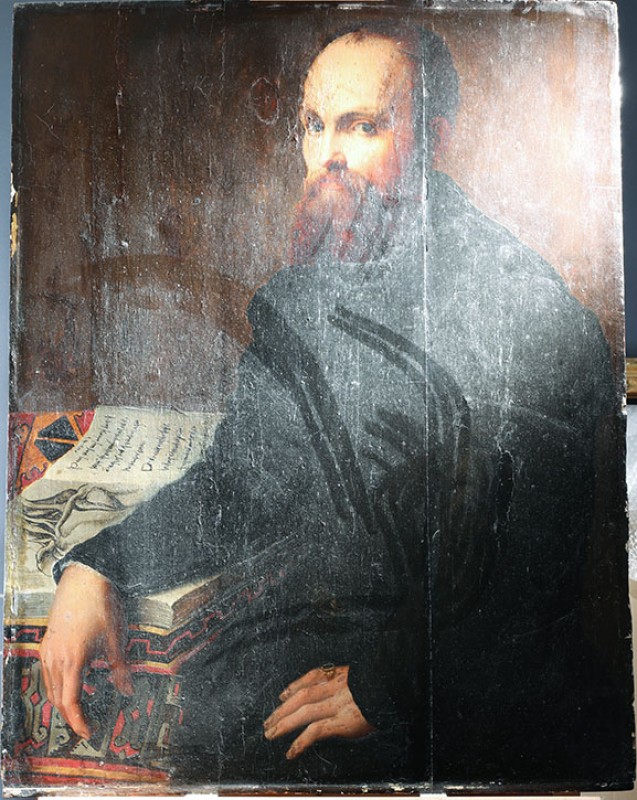

But the picture that most caught my eye, and which I must confess I had glided past on the Art UK database, was a Madonna hanging high over a door in the drawing room.

Looking at it with the advantage of binoculars (an essential part of my stately home visiting kit) I could see that it was a work of great quality, and beauty. 'After Raphael', said the label on the frame, stating it was deemed to be a later copy. But after what?

It seemed there was no known Raphael painting for the Haddo picture to be a copy of. Furthermore, a slight pentimento (or alteration) in the right hand suggested that the picture was in fact unlikely to be a copy, but something painted for the first time. Copyists tend to copy rigidly what they see before them, and don't make changes. And then we found that the picture had been bought as a Raphael, and exhibited as such in 1841 at the British Institution in London. In the same show was the 'Cowper Madonna' by Raphael, today celebrated as an autograph original.

The Virgin

(formerly attributed to Innocenzo Francucci da Imola)

Raphael (1483–1520) (probably)

The Haddo Madonna's spell in the Raphael limelight had been short-lived, however. Soon after the death of the 4th Earl of Aberdeen (who had served as Foreign Secretary and Prime Minister) it was downgraded to a copy, and valued at £80. By 1899 the picture it was deemed to be worth just £20.

But standing in front of the painting, I couldn't help wondering if it might actually be better than everyone had assumed? Our discovery of a drawing by Raphael which followed the outline and features of the Madonna, and showed the same model, suggested for the first time a direct link to a known Raphael composition.

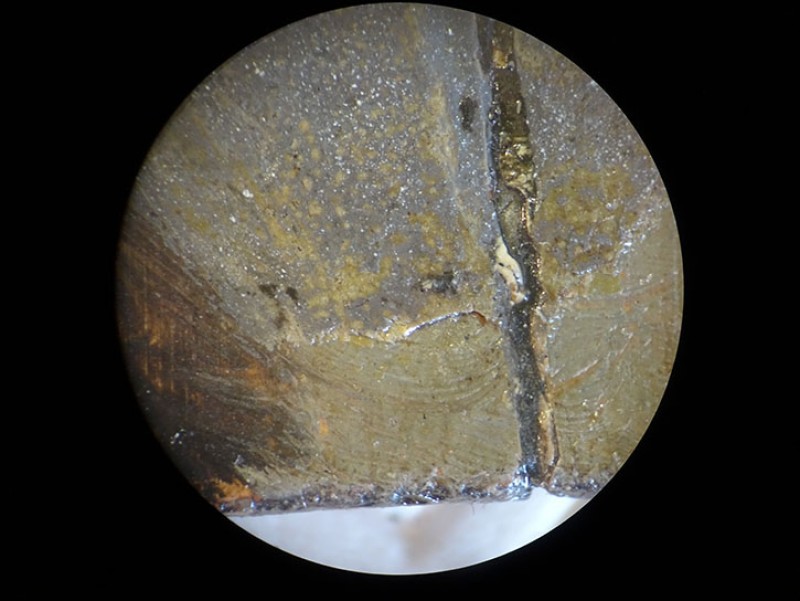

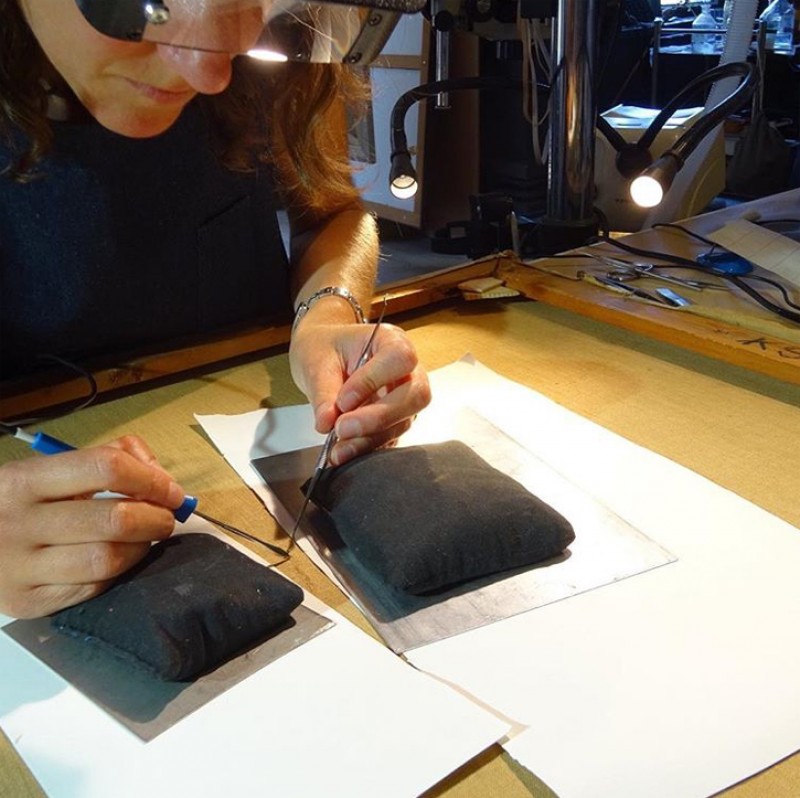

The National Trust for Scotland, who now own the house and its contents, kindly agreed that the picture could be cleaned for the first time in over a century. Layers of dirt and old varnish made it difficult to assess the true quality of the picture beneath. But the quality and technique of many of the details revealed in the conservation studio of Owen Davison in Edinburgh were breathtaking. And after close inspection, the leading Raphael scholar, Sir Nicholas Penny, took the view that what we had uncovered so far was enough to justify an attribution of 'Probably by Raphael'.

All of which is of course tremendously exciting. The picture would be Scotland's only publicly owned Raphael, and could begin a new interest in Haddo House (now suffering cutbacks because of a lack of visitors) and its contents. But the journey has only just begun. I wouldn't dare to suggest that the limited work we have done, and my hunch, means this picture is definitely by such a giant of art history as Raphael. Other scholars will now be given the chance to examine the picture, and more technical analysis – which sadly we had neither the time nor the budget for – will need to be carried out.

But for now the Madonna, cleaned, radiant and as captivating as she no doubt was when the 4th Earl of Aberdeen acquired her, hangs once again in pride of place at Haddo House – a rehabilitated reminder of the Gordon family's love affair with all things Italian.

Bendor Grosvenor, art historian and presenter of BBC Four's Britain's Lost Masterpieces