Over the last six months I've been more grateful than ever for the Art UK website. When the BBC asked for another series of 'Britain's Lost Masterpieces', but this time with four programmes instead of three, to be screened before the end of 2017, I confess that I had a slight panic.

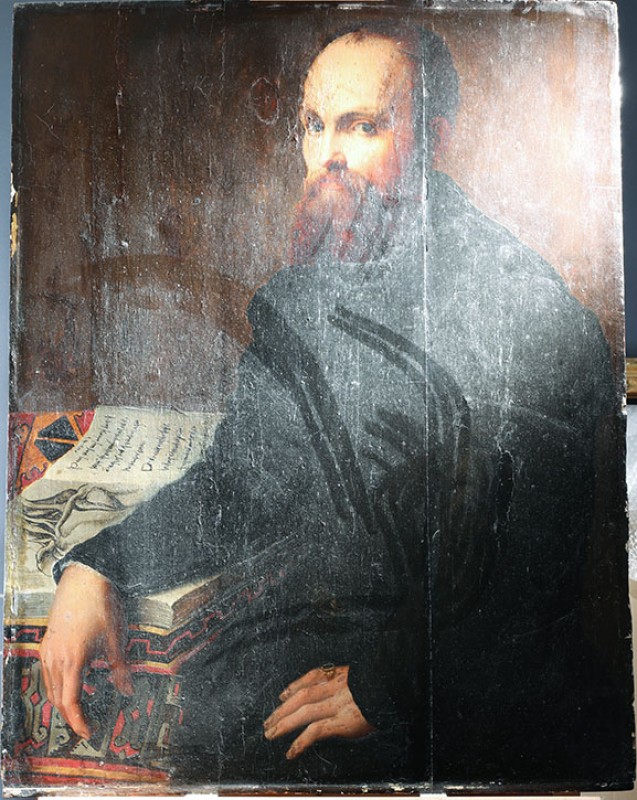

This is no ordinary TV series where a script is written and people say their piece, but one in which valuable, publicly owned paintings are the stars. Our proper care for them takes absolute priority. Then there is the task of finding paintings which will have a good chance of being accepted as 'masterpieces' by experts. I and my production team, along with co-presenter Emma Dabiri, were certainly up for the challenge. But where would we find the paintings and institutions to investigate, in such short time?

'Britain's Lost Masterpieces' presenters, Bendor Grosvenor and Emma Dabiri

And so the clicking and the scrolling began. Now, I may be a little unusual, but searching through web page after page of 'English School', 'Flemish School' and 'unknown artist' paintings is my idea of fun. And not for the first time I found myself offering prayers of thanks for the creators and maintainers of Art UK (and if you've ever supported them with a donation, you too). Being able to search by region, institution and subject matter on the Art UK site is fantastically useful. In no other country is the hunt for lost masterpieces so easy, or so enjoyable.

Sometimes, however, it's easy to miss things. The first time I saw the image for Derby Museum's Landscape with a Ruinous Castle, described as being by an unknown artist, my immediate reaction was, 'what an awful painting'.

The paint was crude and appeared to be entirely twentieth-century in appearance. The way the building (actually a fortified bridge) had been constructed defied the basic laws of physics. And the water in the river flowed uphill. But in fact, it was the picture's very awfulness which made me take a second look. It seemed extraordinary that such a 'bad' picture would ever have been acquired by an important regional museum like Derby's. Was there more here than there first appeared?

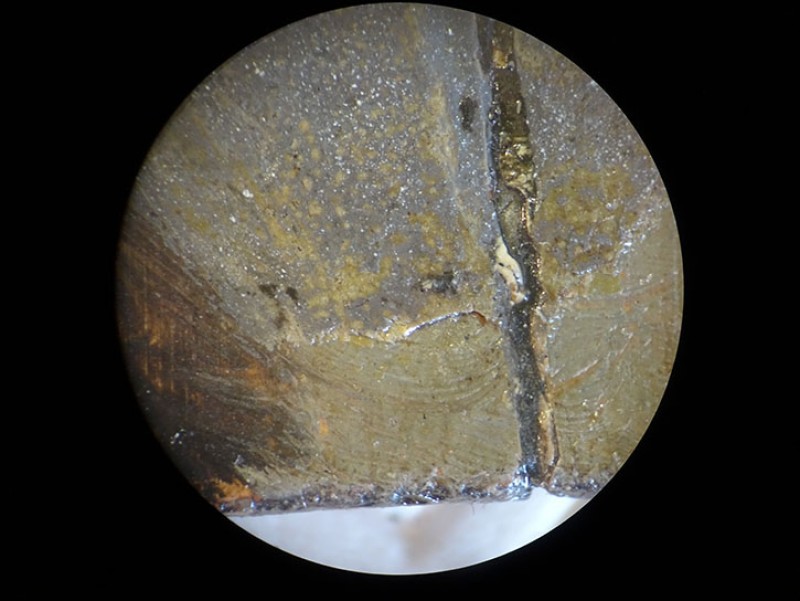

Again, Art UK came to the rescue. A higher resolution image revealed a more complicated work of art than first appeared. At the bottom right-hand corner, I noticed an area of 'sgrafito'. This is where an artist has incised the paint with the handle of their brush, and in this case, the ripples on the water had been created with the 'sgrafito' technique. Very few landscape artists at work in England used this technique – and one of them was Joseph Wright of Derby.

The main principle we rely on to discover artworks for 'Britain's Lost Masterpieces' is connoisseurship. In some art historical circles, this is a term freighted with meaning (such as elitism and notions of 'class'). But actually, it's a very simple concept, which stems from the Latin root of the word, 'cognoscere' – to recognise. In art historical terms, a connoisseur is essentially someone who is able to recognise the artistic techniques of a particular artist, in the way we can all recognise a letter from our mum by seeing her handwriting on the envelope before we find her signature on the letter. Anyone can do it, and it is (or should be) the foundation of all art historical analysis.

Sometimes it is indeed a difficult thing to do; to even begin to know the difference between a genuine Rembrandt and a work by one of his personally trained students takes years of experience, and even then it's a struggle. But many other artists are much easier to get to grips with. And it so happens that Joseph Wright landscapes can sometimes be quite straightforward to identify. For me, in the case of Derby Museum's mystery bridge, it was soon apparent that there was a genuine Joseph Wright here, fighting to get out.

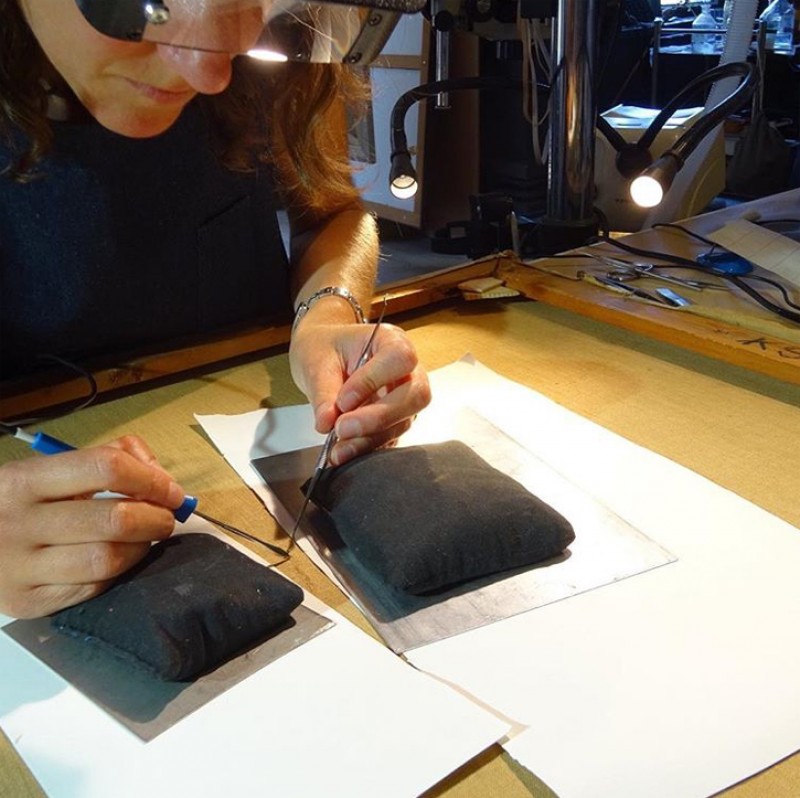

Regular viewers of 'Britain's Lost Masterpieces' will know that we spend a great deal of time undoing the work of earlier restorers. In my experience, 'bad' restoration is the number one reason paintings lose their attribution. A wrong colour in a landscape here, or a wonky eye in a portrait there, and suddenly you can begin to doubt the quality of the whole painting, and thus its attribution.

In the case of Derby Museum's mystery bridge, a local Derby restorer in the 1950s had decided to almost entirely repaint an original work by Joseph Wright. Doubtless, this person (we are not sure exactly who it was) had good intentions. But by the time they had finished, Wright's painting was unrecognisable. The course of the river was altered. The costumes of the figures were refashioned (one now wore a traffic cone). And the colour of the sky was changed from a warm evening pink to a cold blue.

Fortunately, our conservator, Simon Gillespie, was able to remove all of the overpaint with relative ease. The 1950s restorer had used modern paints, and it was a question of finding the right solvents to remove only this paint, and not the much older oil paint beneath. Our further research then identified the bridge in question – the Ponte Nomentano on the River Aniene outside Rome.

This came as a relief, for we know that Wright had been painting bridges on that very stretch of river during his Grand Tour of Italy in the 1770s. The final clue came when we identified, in a sale catalogue of Wright's works from 1801, a View of the Ponte Nomentano near Rome. This picture, which had never been recorded by art historians since, cost the 1801 buyer just £3. Today it's not for sale, but will be treasured by Derby Museum, where it will soon go on display.

It still amazes me that there are unidentified paintings in our national collection like Wright's bridge. Art UK estimates that there are about 30,000 works for which we know neither the artist nor the subject. For 'Britain's Lost Masterpieces' we have so far focused on eleven paintings, and even allowing for some of the heartening and inspired breakthroughs made by members of the public on the Art Detective pages, that still leaves well over 29,000 to be investigated. So my advice to Art UK users is keep scrolling, you never know what masterpieces you might find.

Bendor Grosvenor, art historian and presenter on 'Britain's Lost Masterpieces'