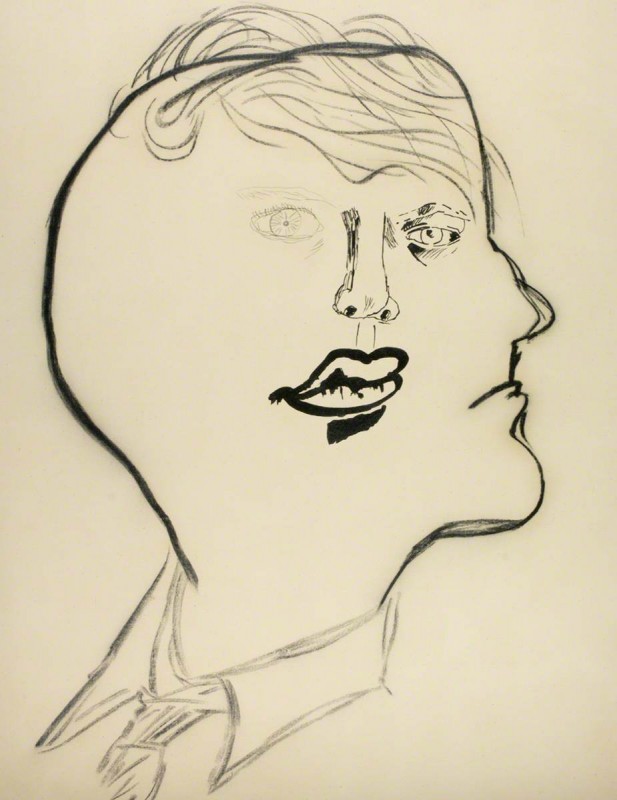

Rembrandt van Rijn (Born Leiden, 15 July 1606; d Amsterdam, 4 October 1669). Dutch painter, etcher, and draughtsman, his country's greatest artist. The son of a prosperous miller, he attended Leiden's Latin school before registering at the city's university in 1620, but he probably never actually studied there. At about this time he was apprenticed to the mediocre local painter Jacob van Swanenburgh (c.1571–1638), with whom he is said to have studied for about three years. However, much more important for Rembrandt's development were six months spent in Amsterdam with Pieter Lastman, c.1624. From Lastman he took not only his predilection for mythological and religious subjects, but also his way of treating them, with exaggerated gestures and expressions, vivid lighting effects, and a meticulous, glossy finish, as in his earliest dated work—the Stoning of St Stephen (1625, Mus. B.-A., Lyons).

The work that most clearly demonstrated his superiority to rivals such as Thomas de Keyser is the Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp (1632, Mauritshuis, The Hague), which brought new vitality and richness to the group portrait. Rembrandt's great energy in his early years in Amsterdam comes out also in his religious works. The most important commission he received during the 1630s was from the Stadholder (head of state) Prince Frederick Henry of Orange for five pictures depicting scenes of Christ's Passion (Alte Pin., Munich), and the Baroque tendencies of his work at this time are even more emphatically expressed in his sensational, life-size Blinding of Samson (1636, Städelsches Kunstinstitut, Frankfurt). Rembrandt presented this picture to the diplomat and writer Constantijn Huygens (1596–1687), who was secretary to the Stadholder and who had probably secured the commission for the Passion series.

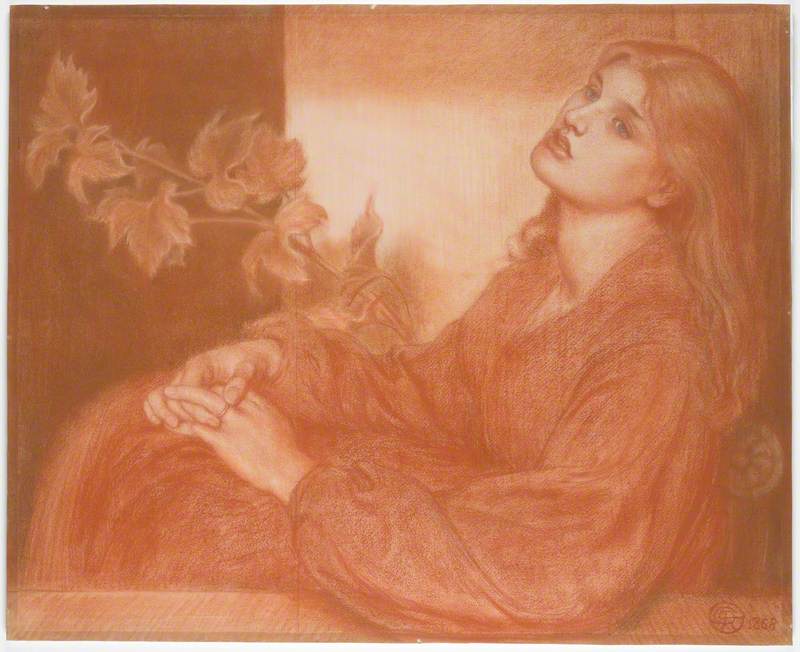

Rembrandt's success in the 1630s was personal as well as professional. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh, cousin of a picture-dealer associate, and from the evidence of his wonderfully tender portraits of her it must have been a blissful union. In 1639 he bought an imposing house (now a Rembrandt museum), and he spent lavishly on works of art and anything else that took his fancy or looked as if it might be useful as a prop—armour, old costumes, etc. His domestic happiness was, however, marred by a succession of infant deaths: of the four children Saskia bore him, only his son Titus (1641–68), who became one of his favourite models, lived longer than two months. Saskia herself died in 1642, and in this year Rembrandt finished his most famous picture, The Night Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), which Jacob Rosenberg, in his standard monograph on the artist, calls ‘a thunderbolt of genius’. The erroneous title dates from the late 18th century when the painting was so discoloured with dirty varnish that it looked like a night scene. Its correct title is The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq and Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch, and it is the culminating work of the Dutch tradition of civic guard portraits (a genre particularly associated with Frans Hals). It is also the most ambitious picture of any kind painted by a Dutch artist up to this date, and Rembrandt showed remarkable originality in making a pictorial drama out of an insignificant event.

To do this he subordinated the individual portraits to the demands of the composition, and according to popular legend the sitters who had paid for the picture were appalled at this and demanded that Rembrandt make radical changes, paint a new picture, or refund their money. Rembrandt's refusal is supposed to have been his downfall and to have led him into penniless obscurity. There is, however, no basis in fact for the story, which seems to be a 19th-century invention; indeed all the available evidence suggests that the picture was well received by contemporaries. Samuel van Hoogstraten, for example, wrote: ‘It is so painter-like in thought, so dashing in movement, and so powerful’ that the pictures beside which it hung were made to seem ‘like playing cards’.

Nevertheless, in the 1640s Rembrandt's worldly success did decline as the direction of his art changed. Formal portraiture took up much less of his time and he concentrated more on religious painting, while his style grew less flamboyant and more introspective. The change has been explained as a response to the death of Saskia (and of his mother in 1640), and religion may well have been a solace to him in this difficult period. At the same time, some of his market in portraiture must have gone to pupils such as Bol and Flinck, who imitated his style so well. It seems just as likely, however, that Rembrandt was tired of routine portraiture and wanted to return to his first love—painting subjects from the Bible. In the 1640s he also developed an interest in landscape and it has been suggested that he spent more time in the countryside during this period to escape from the domestic problems he encountered after Saskia's death. A widow called Geertge Dircx was employed as Titus's nurse, and she sued Rembrandt for breach of promise after his affections turned to Hendrickje Stoffels, a servant some twenty years his junior who entered the household in about 1645. After some unpleasant legal action, Rembrandt succeeded in having Geertge shut up in a reformatory for five years and the litigation did not end until her death in 1656. Hendrickje remained with Rembrandt for the rest of her life and bore him two children, including a daughter, Cornelia, born in 1654, who was the only one of his children to outlive him. Rembrandt's portrayals of Hendrickje are just as loving as those of Saskia, but he was unable to marry her because of a restrictive clause in Saskia's will.

After he turned his back on fashionable portraiture, Rembrandt's extravagance led him into financial difficulties, which became acute by the early 1650s. In 1656 he was declared insolvent (by convincing the authorities that he had acted honestly and in good faith he avoided the worse fate of bankruptcy, which carried the possibility of imprisonment); his collections were sold and by 1660 he had to leave his house and move to lodgings in a poorer district of the city. Houbraken says that ‘in the autumn of his life he kept company mainly with common people and such as practised art’, but the romantic image of him as a pauper and a recluse is grossly exaggerated. He continued to be a respected figure who received important commissions (his patrons included the Sicilian nobleman and collector Don Antonio Ruffo (1610–78), and Hendrickje and Titus established an art firm with Rembrandt technically their employee, a device that protected him from his creditors. Indeed, with some weight thus lifted from his shoulders, Rembrandt may well have felt renewed energy, and there are more dated paintings from 1661 than from any year since the early 1630s. In 1661–2 he painted two of his greatest works—The Sampling Officers of the Cloth-Makers' Guild (sometimes called The Syndics, Rijksmuseum) and The Conspiracy of Claudius Civilis, painted for Amsterdam Town Hall, but for unknown reasons removed in 1663 and cut down (evidently by Rembrandt himself)—the magnificent fragment is now in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm.

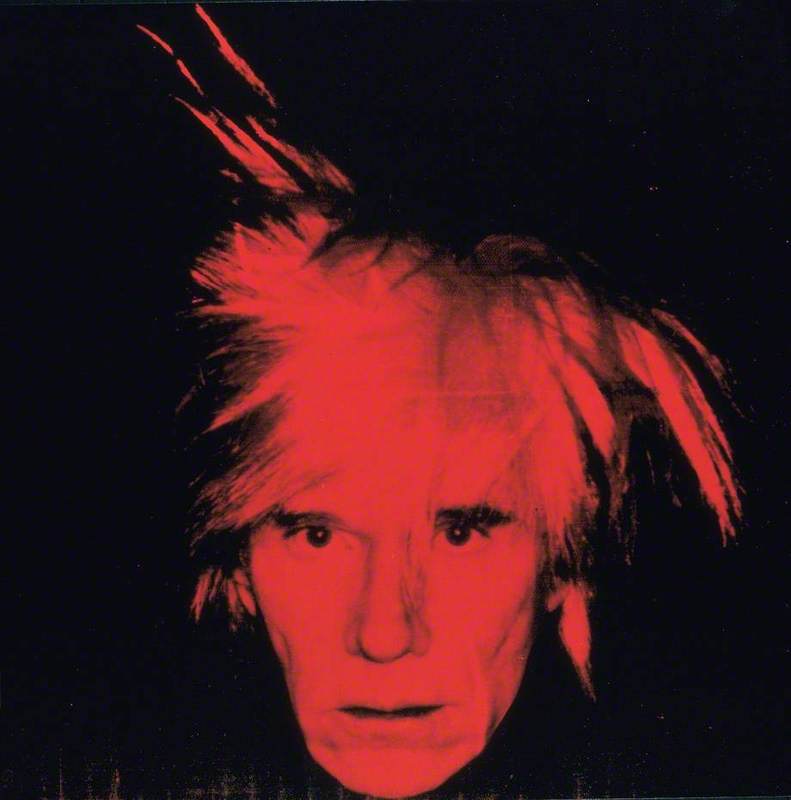

Rembrandt's final years were clouded by the deaths of Hendrickje in 1663 and Titus in 1668, but his art was in no way impaired. On the contrary, his work seemed to grow in human understanding and compassion to the very end, and his last self-portraits, the culmination of an incomparable series that began 40 years earlier, show him facing his hardships with the utmost dignity—someone who has no illusions about life, but equally no bitterness. Two self-portraits date from the last year of his life (NG, London, and Mauritshuis), but the painting that best stands as his spiritual testimony is perhaps The Return of the Prodigal Son (c.1669, Hermitage, St Petersburg), a work of the utmost tenderness and poignancy, described by Kenneth Clark as ‘a picture which those who have seen the original…may be forgiven for claiming as the greatest picture ever painted’.

The emotional depth and range of Rembrandt's work was matched by the expressive mastery of his technique. Even as a young man, when surface polish and attention to detail were a necessary part of his skill as a fashionable portraitist, he had experimented boldly in his more private works, sometimes, for example, using the butt end of the brush to scrape through the paint. When he began to paint more to please himself in the 1640s, his handling grew much broader, and Houbraken wrote that ‘in the last years of his life, he worked so fast that his pictures, when examined from close by, looked as if they had been daubed with a bricklayer's trowel’.

It is not only the quality of Rembrandt's work that sets him apart from all his Dutch contemporaries, but also its range. Although portraits and religious works bulk largest in his output, he made highly original contributions to other genres, including still life (The Slaughtered Ox, 1655, Louvre, Paris), and he painted some pictures, such as The Polish Rider (c.1655, Frick Coll., New York), that virtually defy classification. Rembrandt was prodigious, too, as an etcher and draughtsman. He is universally regarded as the greatest of all exponents of etching (and drypoint), capable of expressing the airy breadth of the Dutch countryside with a few quick strokes, but also prepared to radically rework a complex religious scene such as The Three Crosses perhaps a decade after he had begun it in 1653 to create one of the most awesome of all images of Christ's Passion. His drawings were done mainly as independent works rather than as studies for paintings and often with the thick bold strokes of the reed pen, of which he was an unsurpassed master.

Rembrandt was the most renowned teacher of his day: Gerrit Dou became his first pupil in 1628 and Aert de Gelder, who was with him in the 1660s, continued his master's style into the 18th century. Between these two, Rembrandt taught such illustrious figures as Carel Fabritius (his greatest pupil), Philips de Koninck, and Nicolaes Maes. He continued to have many admirers after his death, and his work often fetched high prices in the 18th century. He was generally regarded as incomparable in his mastery of light and shade, but most critics considered him a flawed genius, whose failing was his ‘vulgarity’ and lack of decorum. It was during the age of Romanticism, when it was felt that artists should give expression to their innermost feelings and flout conventions, that his reputation began to rise towards its present supremely exalted heights. In 1851 Delacroix suggested that one day Rembrandt would be rated higher than Raphael—‘a piece of blasphemy that will make every good academician's hair stand on end’; his prophecy came true within 50 years.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)