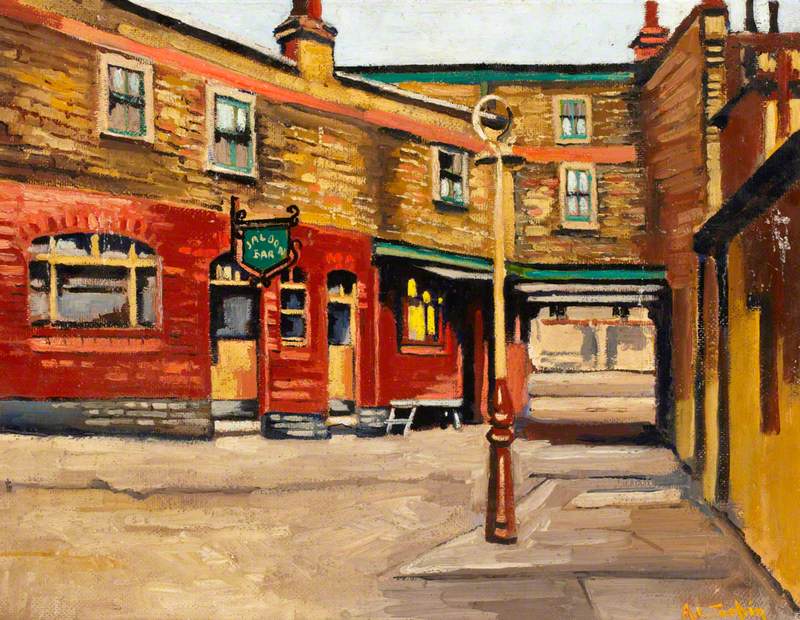

Alfred Aaron Wolmark (1877–1961) was born in Warsaw and emigrated to England with his family at the age of six to escape the persecution of the Jews in his native land. They first moved to Devon and then to the East End of London, home to a dense population of Jewish immigrants.

Wolmark's Jewishness meant a great deal to him. His formative years in the East End, followed by two stays in Poland in 1903–1905 and 1905–1906, nourished his appetite for Jewish life and culture and provided visual material for a series of paintings of Jewish subjects. In the Carpenter's Shop, for instance, drew on his East End experience.

Born Aaron Wolmark, he adopted the very English name Alfred in the late 1890s, around the time he trained at the Royal Academy, but as an artist, he made his position clear: 'If we Jews want to produce great works of art we must do so as Jews not as Englishmen, Frenchmen or any other men… only as Jews can we produce the great… I insist on Jewishness in Art. Individuality of your Race expressed in your art.'

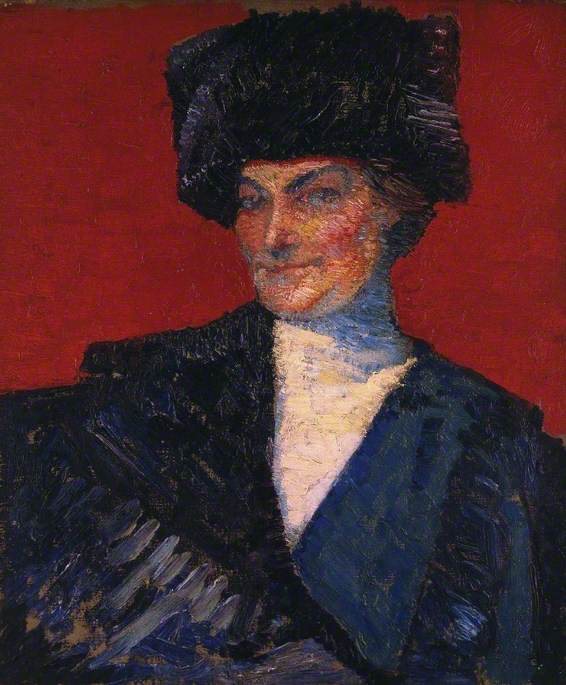

Wolmark claimed that Rembrandt was the only artist who influenced him. In fact, Rembrandt had a powerful effect on a number of Jewish artists of the late nineteenth century onwards, such as David Bomberg, Chaïm Soutine and Lucian Freud. It is thought that Wolmark visited a Rembrandt exhibition in Amsterdam in 1898, a trip paid for by Anna Wilmersdoerffer, a German-Jewish emigrée who vigorously championed him in his early years – she organised his first solo exhibition at Bruton Galleries in London in 1905. The Cossack Hat is an arresting portrait of her from around 1911.

Rembrandt's attraction for Jewish artists is based on what critic Simon Schama calls 'an imagined biography of Rembrandt's life and work in which he features as the epitome of the outsider artist: temperamentally hostile to academic classicism; uninhibitedly and theatrically expressive; increasingly engaged with interiority and spirituality, and above all a dramatist of the paint surface'.

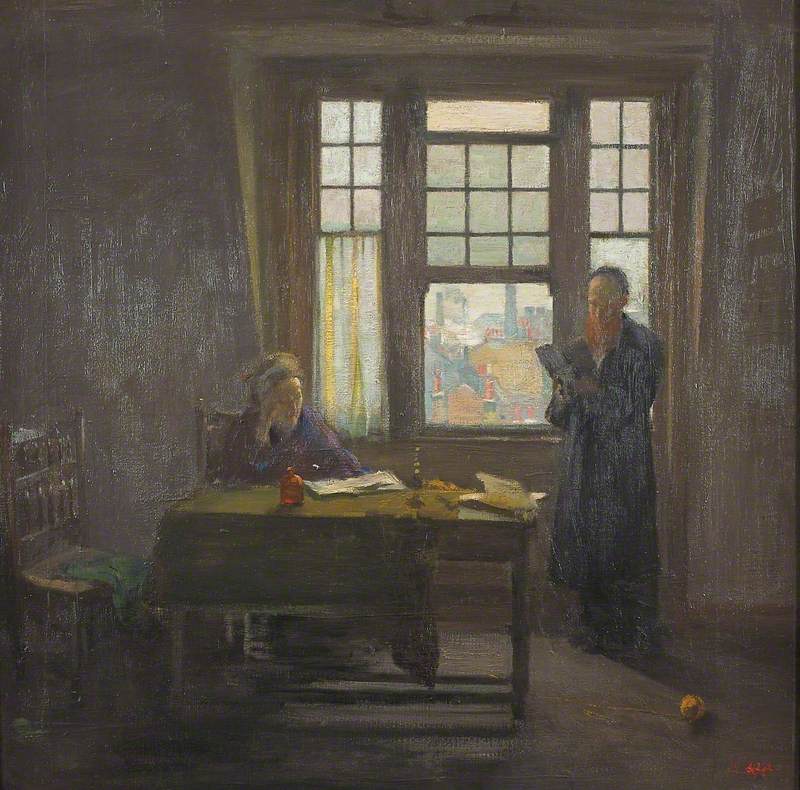

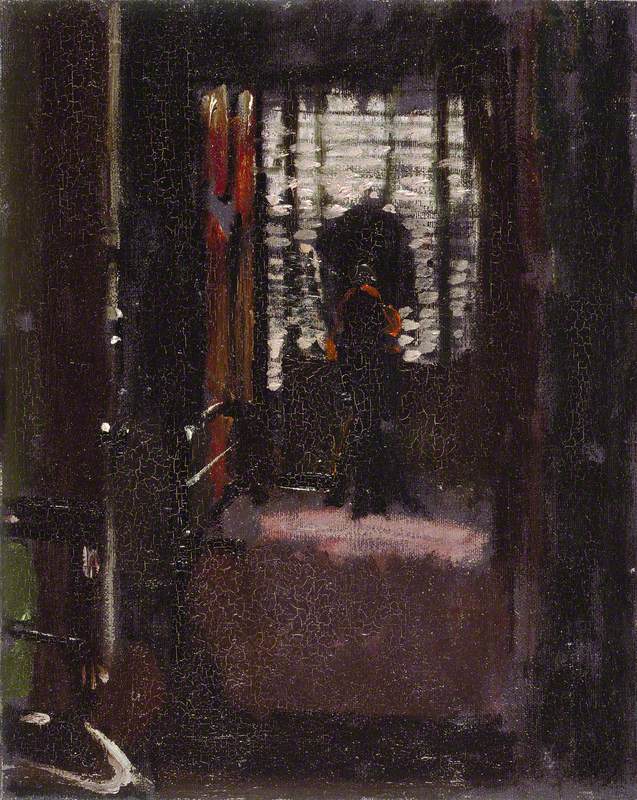

Rembrandt's dark palette and chiaroscuro became Wolmark's adopted style in his early Jewish pictures, such as Sabbath Afternoon, in which the observant couple are staged in gloom, while light and the suggestion of the world without can be seen through the open window. A ball of wool, dropped on the floor, will remain there while the Sabbath lasts.

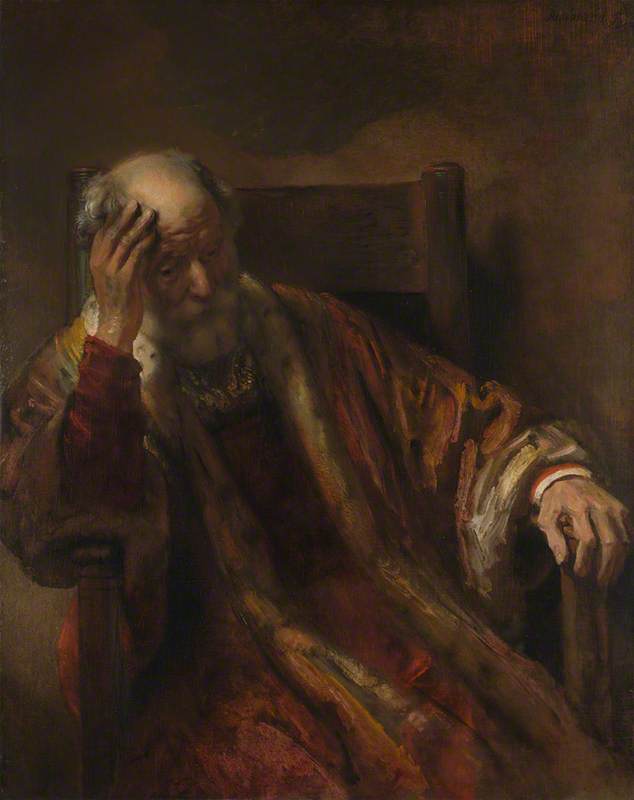

There is something in the sad, meditative figures of Rembrandt that appeals to the Jewish artist. Wolmark's moving study of prayer In the Synagogue, recalls the old master's An Old Man in an Armchair in the figure's pose and the emphasis on the hands.

An Old Man in an Armchair

1650s

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) (probably)

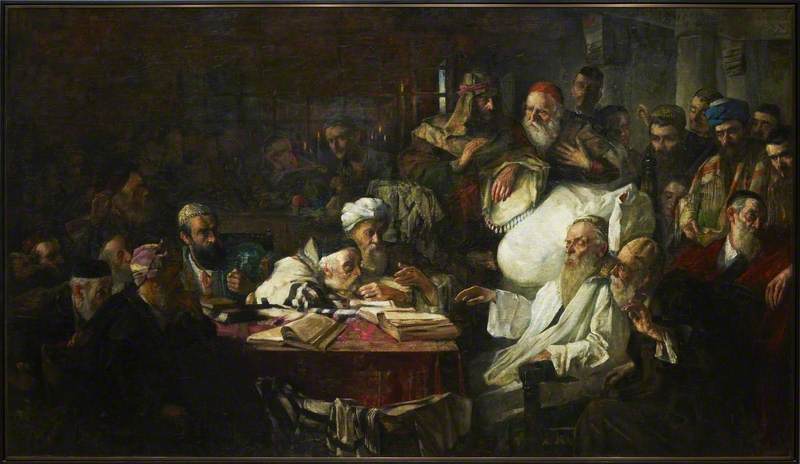

The Last Days of Rabbi Ben Ezra, painted in 1905 and employing studies of Jewish figures made during Wolmark's stays in Poland, is ambitious in its scale and subject matter. A historical, multi-figure scene painted in dramatic chiaroscuro, it recalls Rembrandt's larger canvases, as well as the epic works of the Polish artist Jan Matejko (1838–1893). The painting was inspired by a poem by Robert Browning and depicts the death of Ezra, a venerable scholar looking forward to death: 'Grow old along with me! The best is yet to be…'

Browning had considerable regard for Jews and Judaism, and Wolmark's painting was first exhibited at the time of the passing of a notable act of Parliament which aimed to restrict the entry of Jewish immigrants to Britain. As Norman L. Kleeblatt argues: 'Wolmark's use of the Browning poem operates as both an act of cultural identity and a defence of his people.' The topicality of the work, and Wolmark's personal identification with the subject, are signalled by the inclusion of a self-portrait in the middle background of the painting.

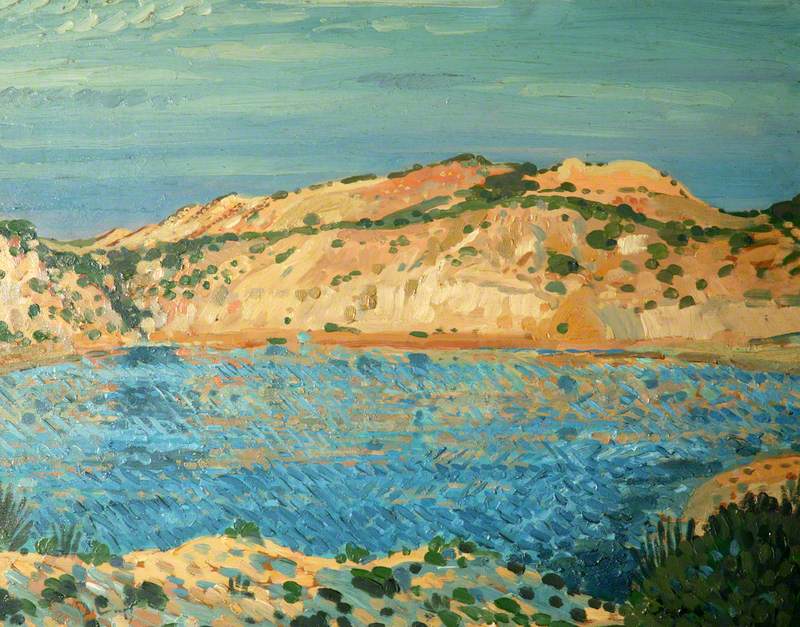

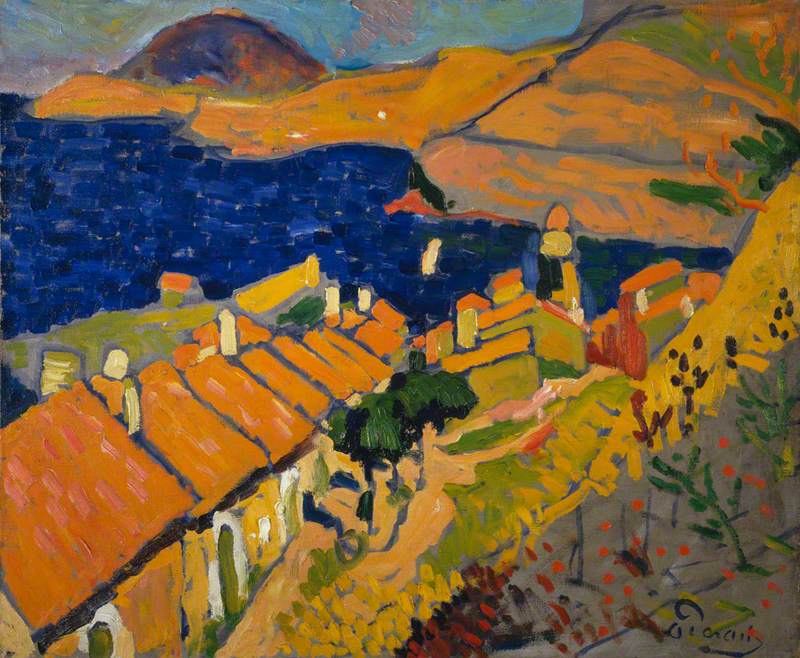

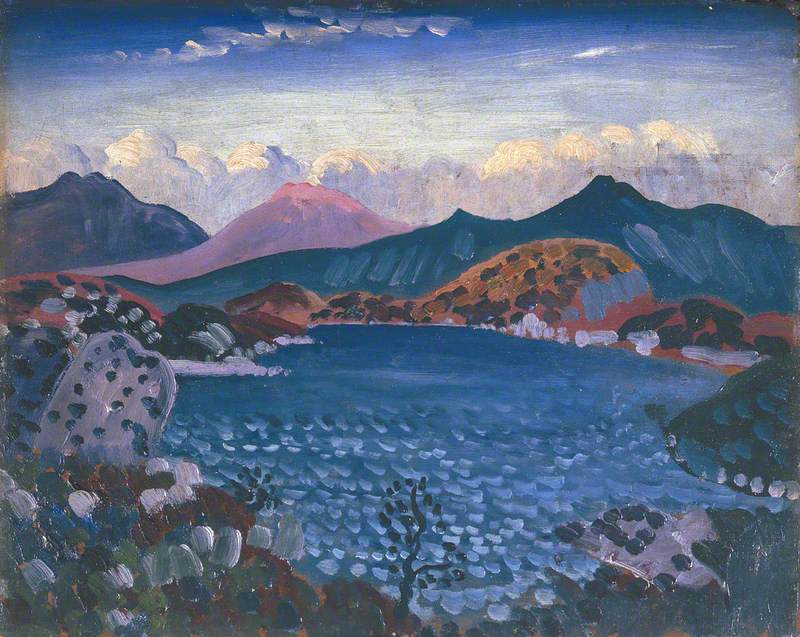

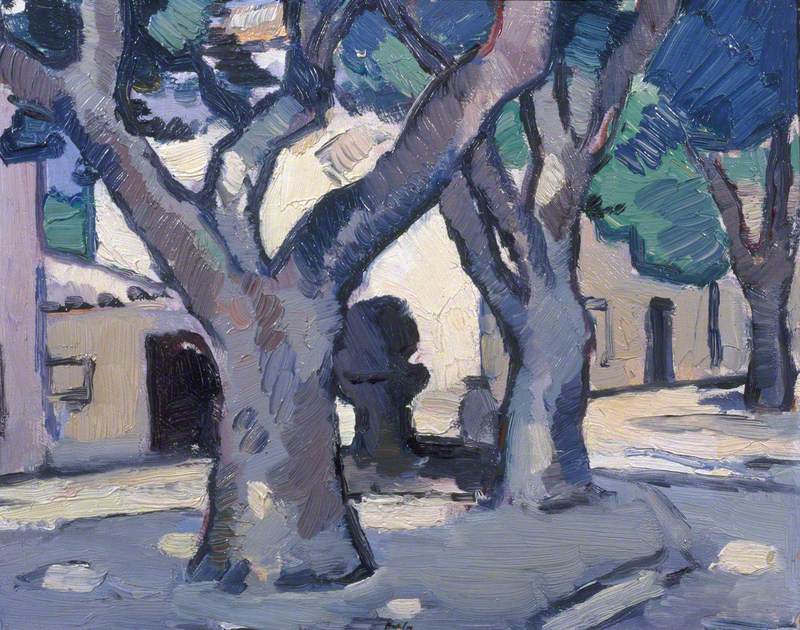

At a time when European art encompassed Henri Matisse's bold Fauvism, when the expressionist group Die Brücke was forming in Germany, and several years after Edvard Munch's The Scream – all high points of early Modernism – Wolmark's Jewish works are solidly traditional. However, in 1911 Wolmark married Bessie Tapper and their summer honeymoon in Concarneau on the Brittany coast sparked a revolution in his painting.

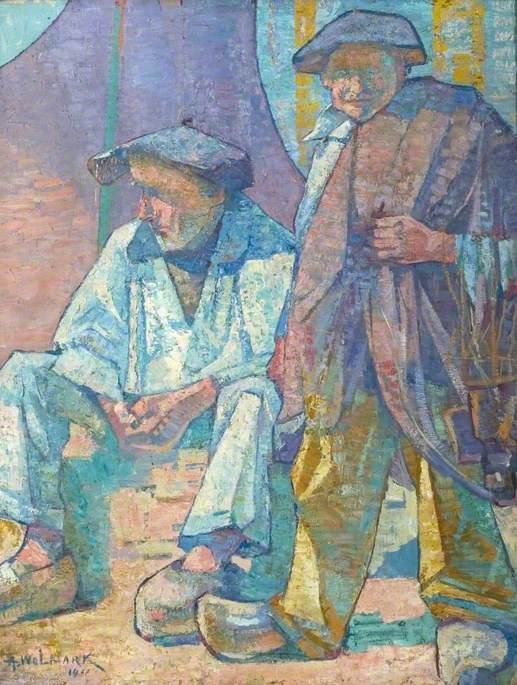

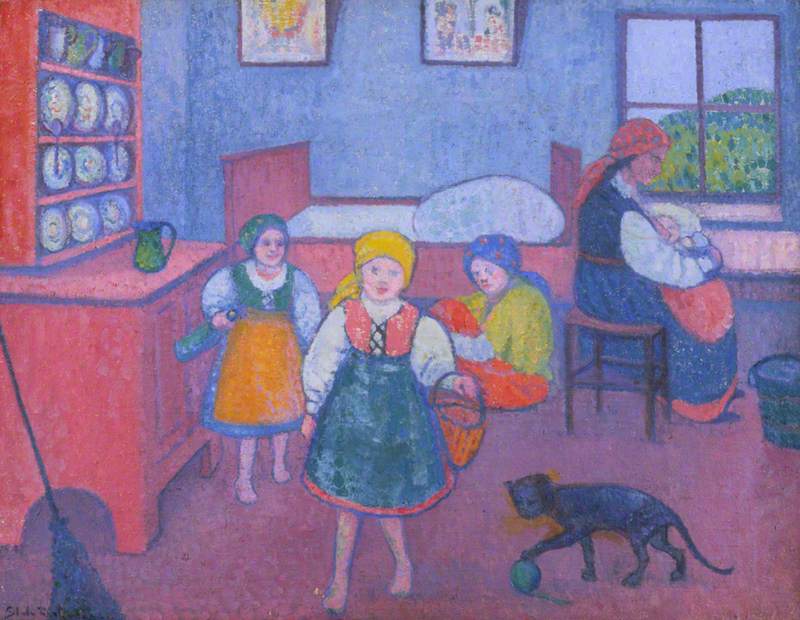

Like Vincent van Gogh, he turned from a muted palette to brilliant colour, and, like Van Gogh, this transformation was prompted by a relocation to an exotic setting. As Van Gogh discovered the light of Arles, so Wolmark found the colours of Concarneau. The Two Breton Fishermen at Concarneau seem to squint in this revelatory light, which shimmers in daubs of colour – colours which have become non-naturalistic as blue and green shadows on their faces and on the ground.

Wolmark obviously delights in the strong colours in Fisher Girl of Concarneau. Again, the summer light saturates the image, but the girl's individuality is less important than her form (in fact, she turns away, as though hiding her identity). Behind her, there is abstraction in the coloured planes which might be sails.

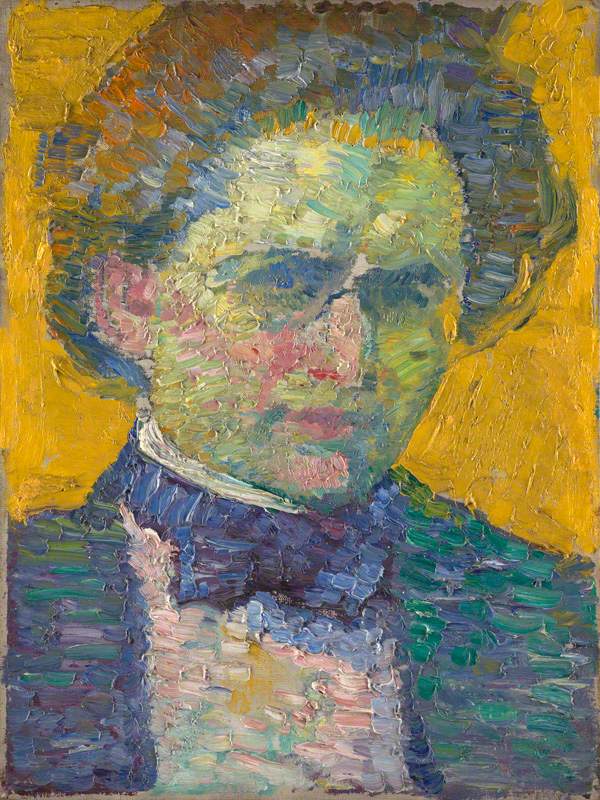

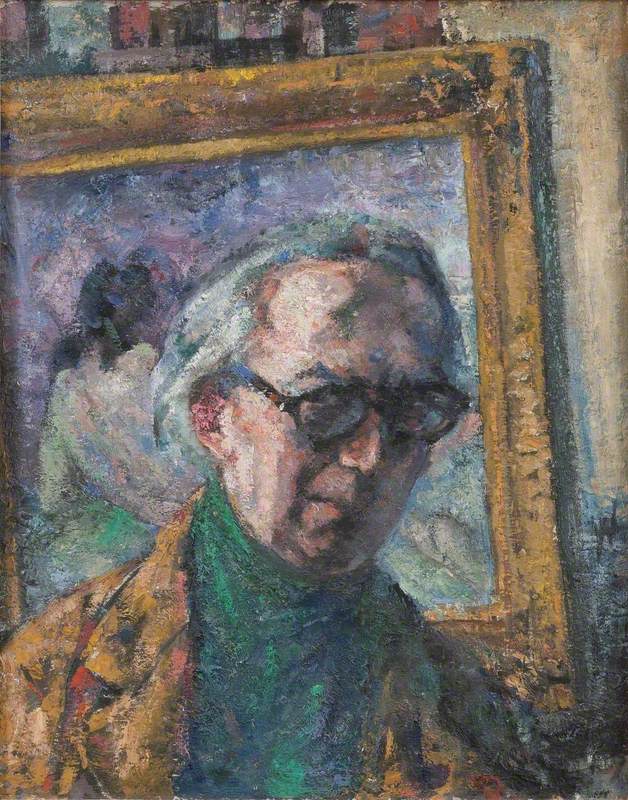

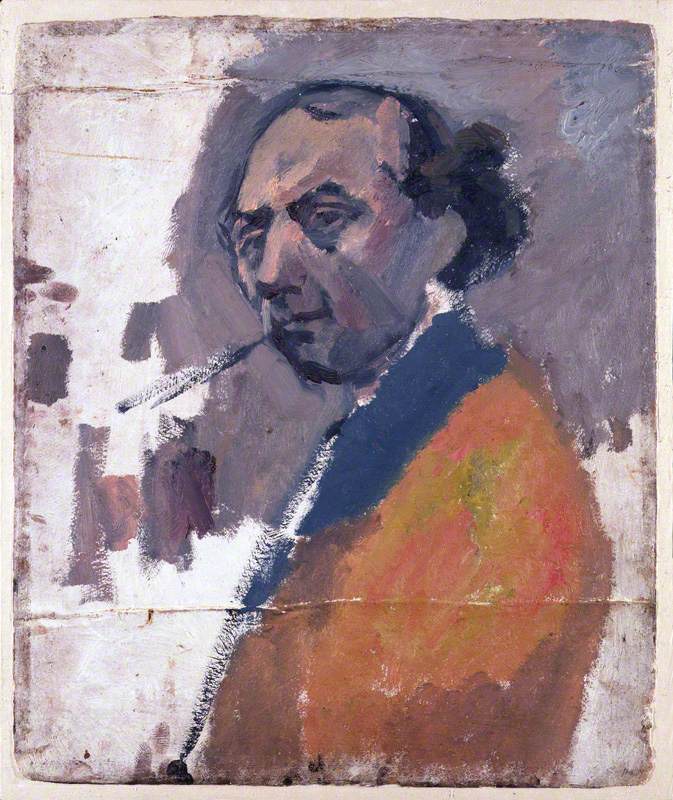

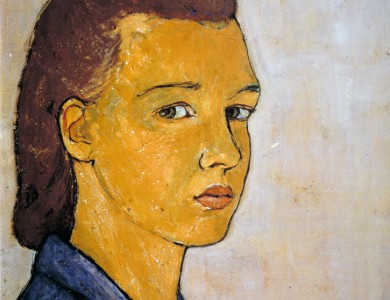

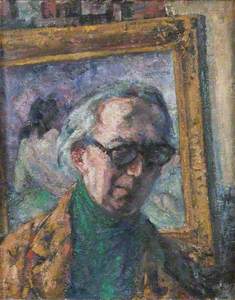

Wolmark's stylistic transformation is clear from two self-portraits: a 1902 work composed in deeply shadowed, Rembrandtesque tones, and the boldly expressionistic image of 1911.

Portraiture was a significant part of Wolmark's output. The 1904 portrait of Dr Marie Stopes was made soon after she became the youngest person to obtain a DSc qualification in Britain, followed swiftly by a PhD. Her academic robes dominate the picture: Wolmark seems concerned to celebrate her scholarly achievement, while her expression appears nervous and uncertain.

This extraordinary woman would later found the first birth control centre in Britain, but as a pioneering woman in academia, this portrait evokes a distinct sense of apprehension.

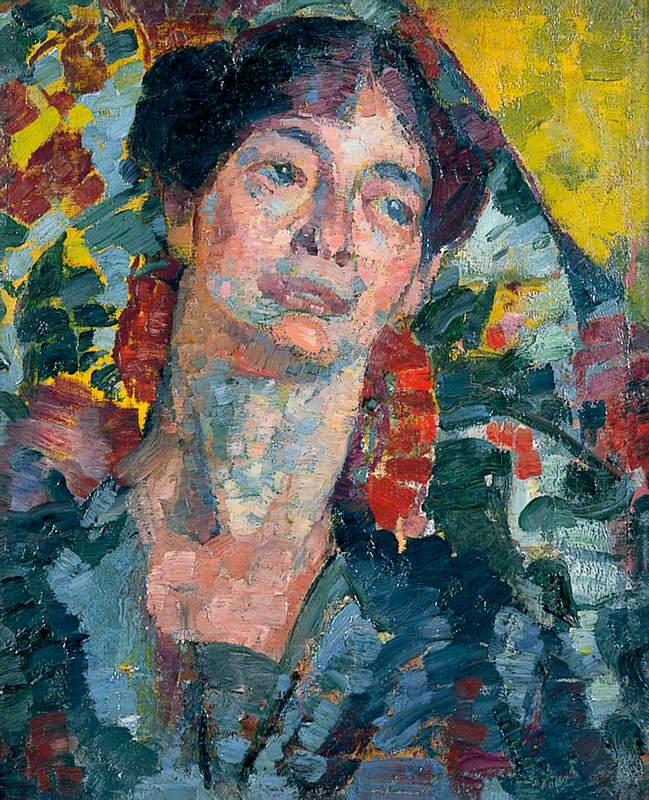

Once again, a comparison with a later portrait demonstrates Wolmark's development. Portrait of an Unknown Woman (who uncannily resembles Stopes) is a work under the spell of European expressionism and the Fauvism of Matisse, and indeed Wolmark later earned the sobriquet a 'British Fauve'.

Roger Fry's London exhibition, 'Manet and the Post-Impressionists' in the winter of 1910–1911, inspired enormous interest in artists from Manet to Matisse. Wolmark could not ignore the stylistic developments occurring elsewhere, and from 1911 he became a different artist – a colourist – and gained a reputation as a leading British modernist.

Writer Joseph-Emile Muller eloquently expressed the Fauvist's approach: '… the colours the artist brings into play are taken from his palette and not from nature. These pinks, mauves, and bluish greens, these bright reds, oranges, purples, these pale or fully saturated blues, all these are colours which are invented rather than observed… their aim is not to reproduce the appearance of the visible world, but to transpose by means of colour the artist's sensations in the presence of nature.'

This use of colour is unlikely to perturb the twenty-first-century viewer, but at the time these early forays into post-Impressionism provoked critical disapproval. Wolmark himself claimed that his new works attracted 'an avalanche of hostile criticism' and his heavy use of impasto (layers of thickly applied paint) drew from fellow artist Walter Sickert the view that 'You cannot see Mr Wolmark's pictures for the paint'.

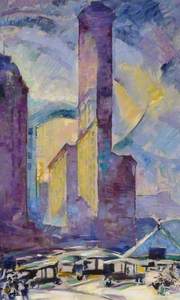

In 1919 Wolmark travelled to New York and made paintings of the city's skyscrapers. His two versions of the Flatiron Building – phallic and foreboding – are remarkable for their colouristic and formal daring.

Wolmark demonstrated how an artist's motivation can turn from assertions of personal identity to concerns of an overriding aesthetic nature. His transformation was like a curtain thrown open and a room flooded with light.

He applied his talents in a variety of ways, from pottery and stage design to sculpture and illustration. In 1915 his design for an abstract stained-glass window for St Mary's Church, Slough, was realised. But his last decades were not marked by distinguished work and his urge to experiment declined. He kept painting, remained resolutely proud and independent, and somewhat bitter at his lost recognition.

Wolmark's story is of the move from the faithful, studied world of the old art to the liberated, instinctive licence of modernism. Although his star waned, we can imagine him in old age reflecting on those days when, according to curator Anthony d'Offay, 'his work was as advanced as any painter in England', and when (as he proudly claimed) his paintings were once hung alongside Van Gogh's as the only artist whose startling colours could bear comparison.

Adam Wattam, writer

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Rachel Dickson, et al., Rediscovering Wolmark: a pioneer of British modernism, Ben Uri Gallery, 2004

Maurice Gordon, 'The Resurrection of Wolmark' in Art and Artists 5, no. 3, 1971

Norman L. Kleeblatt, 'Master Narratives/Minority Artists' in Art Journal57, no. 3, 1998

Joseph-Emile Muller, Fauvism, Thames & Hudson, 1967

Lisa Tickner, Modern Life and Modern Subjects: British Art in the Early Twentieth Century, Yale University Press, 2000