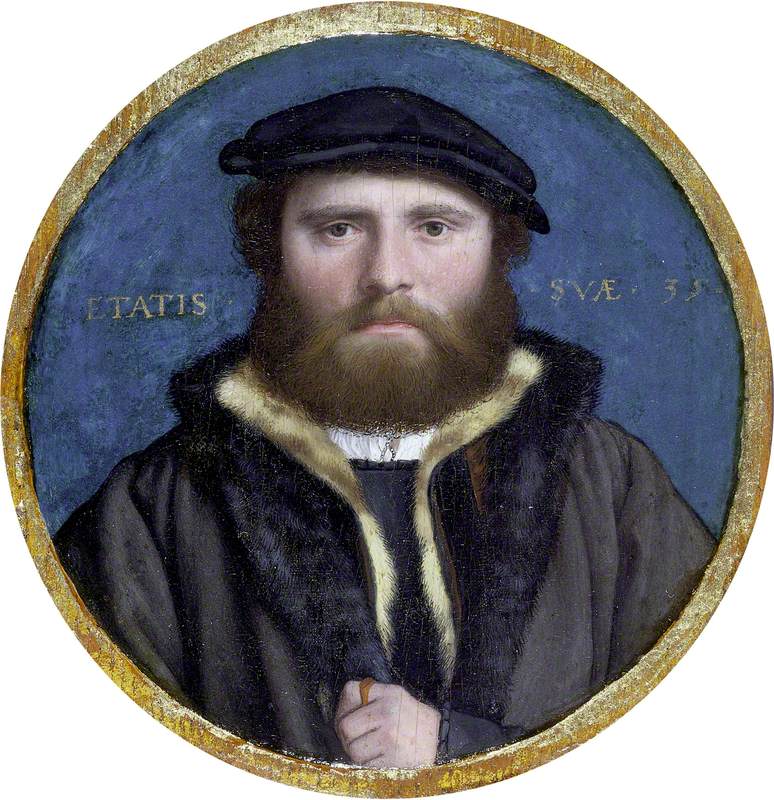

Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve ('The Ambassadors') 1533

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543)

The National Gallery, London

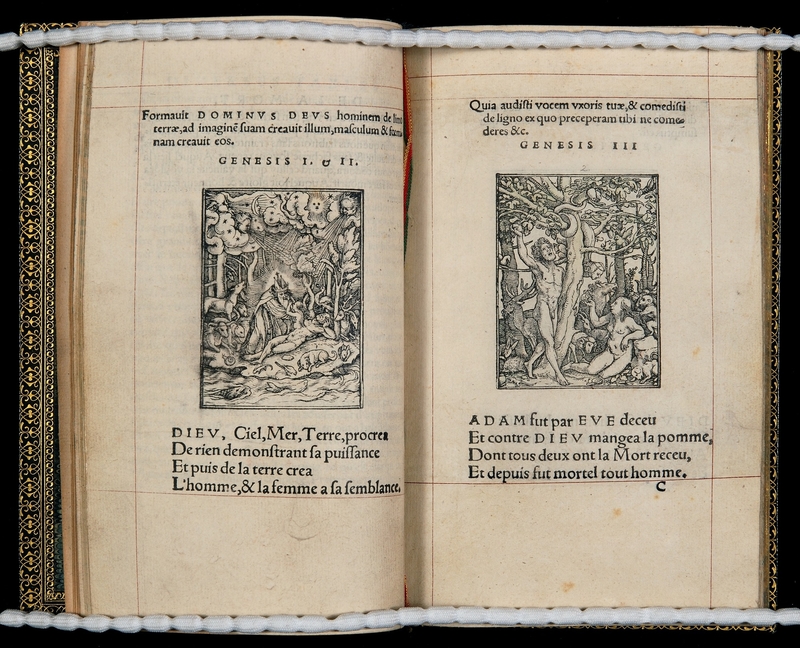

(Born Augsburg, probably 1497; died London, Oct./Nov. 1543). German painter and designer, chiefly celebrated as one of the greatest of all portraitists. He trained in Augsburg with his father, Hans Holbein the Elder (c.1465–1524), one of the leading artists of the day there; his brother, Ambrosius (c.1494–?c.1519), was also a painter. By 1515 the brothers had moved to Basle. There Hans quickly found employment as a designer for printers, and in 1516 he painted portraits of Jacob Meyer, mayor of the city, and his wife (Kunstsmuseum, Basle). From 1517 to 1519 he worked in Lucerne, assisting his father on the decoration of a house for the city's chief magistrate (only a fragment of the work survives, in the Lucerne museum). It is possible that during this time Holbein crossed the Alps to Lombardy, for on his return to Basle, where he was to remain until 1526, his work had more dignity and authority and his modelling had become softer. The harrowing Christ in the Tomb (1521 or 1522, Kunstmuseum, Basle), for example, has a power of expression combined with a mastery of chiaroscuro that almost rivals Leonardo.

The disturbances of the Reformation meant a decline of patronage in Basle, and in 1526, armed with an introduction from Erasmus to Sir Thomas More, Holbein sought work in England. His great group portrait of the More family (lost, but later copies in NPG, London, and Nostell Priory, Yorkshire) is a landmark in European art, for no previous artist had produced a group portrait of full-length figures in their own home. A number of single portraits of eminent sitters also date from this visit and Holbein seems to have prospered financially. However, in 1528 he returned to Basle, probably because there was a risk of losing his citizen's rights if he were absent too long. He bought a house in the city soon after his return and again was in demand for a variety of work. His biggest commission in Basle was the decoration of the council chamber of the town hall with murals (of which only fragments remain) on the theme of Justice; they were begun in 1521 and completed after his return from England. While he had been away the religious strife in Basle had intensified, and in 1532 he returned to England, leaving behind his wife and two children. He saw them only once more, on a brief visit to Basle in 1538, and was based in London for the rest of his life.

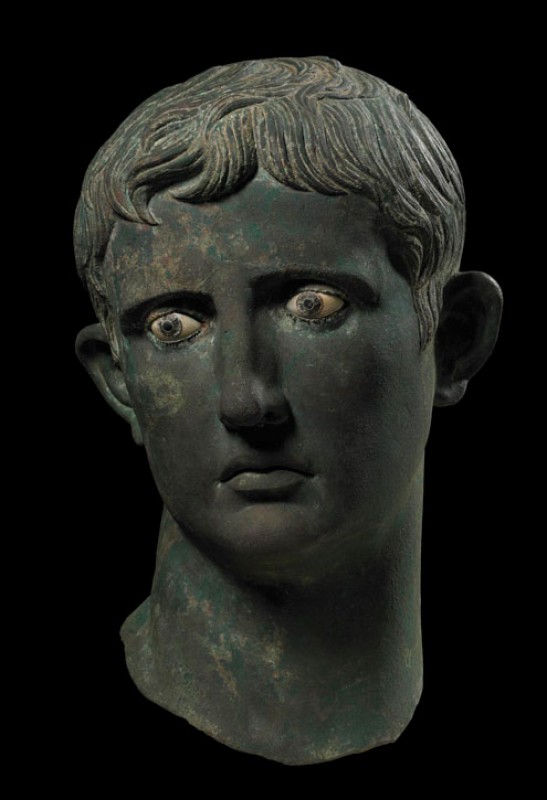

England too had changed since his first visit. More had resigned as lord chancellor and gone into retirement and members of his circle who had patronized Holbein were similarly out of favour. He found new patrons among the prosperous German merchant community in London, and in about 1533 he painted a portrait of Thomas Cromwell (Frick Coll., New York), soon to be Henry VIII's secretary. Cromwell may have obtained for Holbein the commission for his celebrated double portrait The Ambassadors (1533, NG, London), and almost certainly helped him to gain royal patronage. By 1536 he was working for the king, and in the next year he produced the work that his contemporaries regarded as the masterpiece of his English years, the wall painting in Whitehall Palace of Henry VIII with his father and mother and his third wife, Jane Seymour. Though the picture perished in a fire in 1698, part of the cartoon survives (NPG, London) and the massively assertive full-length figure of the king is well known through copies. Visitors to Whitehall Palace are said to have been ‘abashed’ and ‘annihilated’ by this overpowering image of royal authority. The only portrait of the king indisputably from Holbein's hand is a bust-length picture in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, a type of which numerous replicas exist.

After Jane Seymour died in childbirth in 1537, Holbein was sent abroad several times to produce portraits of prospective brides for Henry. Most of these pictures are lost, but two major works survive—Christina, Duchess of Milan (1538, NG, London) and Anne of Cleves (1539, Louvre). Henry married Anne in 1540 but had the union annulled a few months later without consummating it. According to popular tradition, he had been misled by Holbein's portrait, but it was evidently Anne's dullness rather than her looks that disappointed him, and he blamed his ambassadors' reports, not his artist's likeness. Numerous other members of the court were portrayed by Holbein, in paintings and in drawings, a superb collection of which is in the Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Holbein also made many designs for the royal household, ranging from substantial architectural elements to buttons, but there are no surviving objects based on his drawings. At about the time he entered royal service he also took up miniature painting, to which his exquisitely detailed craftsmanship was eminently suited. Holbein's portraits were much copied, but none of his followers in England approached the penetration of his characterization or the virtuosity of his technique. Only in miniature painting did he have a worthy successor in Hilliard.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)