There has been scant representation of facial disfigurement in portraiture through the ages. Reasons include the frequent emphasis in art on beauty, symmetry and proportion, the need for the artist to sell his or her work, and the widespread tendency in commissioned work for the artist to flatter the sitter to indicate wealth, status and power. Sitters with unusual faces often required artists to conceal or disguise any facial differences.

Anne of Cleves (1515–1557)

c.1780

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543) (copy of)

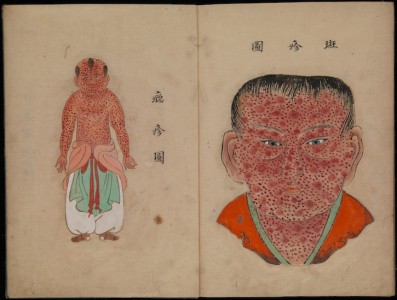

Henry VIII instructed Hans Holbein to provide an honest portrait of his fourth wife Anne of Cleves but Holbein omitted her smallpox scars. Elizabeth I was badly scarred after contracting smallpox in 1562 but heavy makeup and compliance by court artists concealed these imperfections.

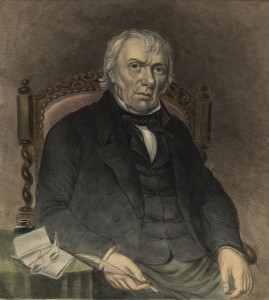

William Roos's portrait of the Welsh preacher Christmas Evans (1766–1838), scarred and blinded in one eye during a youthful brawl, reveals his blindness but does not depict scarring.

Reverend Christmas Evans (1766–1838)

1835

William Roos (1808–1878)

Occasionally, however, sitters acknowledged that distinguishing facial marks make them more recognisable. Oliver Cromwell famously took control of his own image, demanding of Samuel Cooper (not Peter Lely as generally believed) that he be depicted with 'pimples, warts and everything.'

Oliver Cromwell

(copy after an original of 1656)

Samuel Cooper (1609–1672) (copy after)

Religion played a role in the portrayal of people with disfigurements. Some societies believed that evil and deviation were indelibly marked upon the face, a stereotype that continues today. Modern medicine can provide retrospective diagnosis of disfiguring ailments, requiring reinterpretation of portraits depicting those formerly labelled 'freaks'.

Quinten Massys' portrait An Old Woman ('The Ugly Duchess') (c.1513), was cruelly satirical. To contemporary spectators her physiognomy hinted at vice and animalistic desires.

An Old Woman ('The Ugly Duchess')

about 1513

Quinten Massys (1466–1530)

Recent diagnosis of her condition as an advanced form of Paget's disease discomfits the spectator and demands a more sympathetic viewing.

Lavinia Fontana's Portrait of a Girl Covered in Hair presents a hirsute child. She and her family were accepted by society due to the belief that divine purpose lay behind their unusual appearance. Nevertheless they were objects of curiosity among the courts of Europe, their hirsuteness equating them with 'werewolves'. Recent diagnosis of their condition as a rare genetic disorder requires today's spectators to adjust their gaze accordingly. There is a similar portrait of Barbara van Beck in Wellcome Collection.

Barbara van Beck (b.1629)

c.1650

Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri (1589–1656) (attributed to circle of) and Italian (Lombard) School (attributed to)

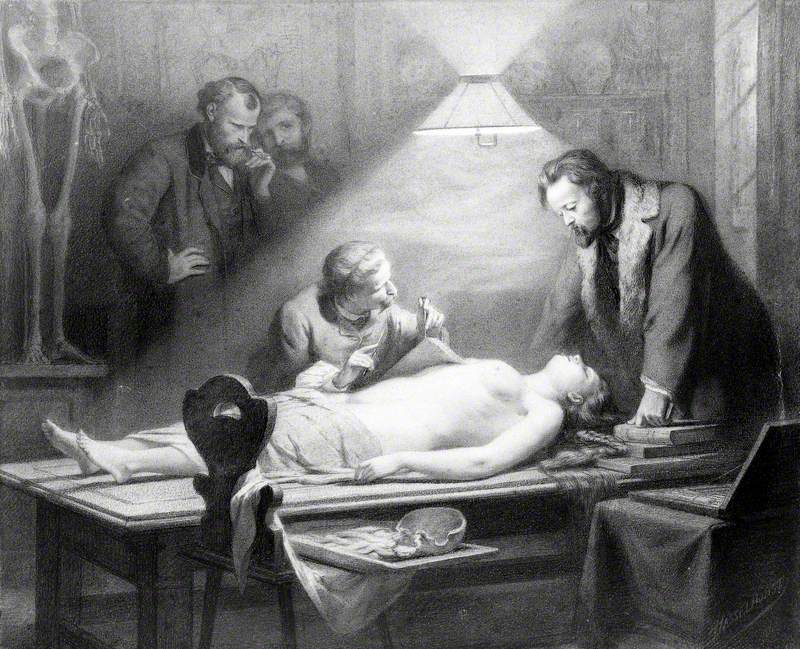

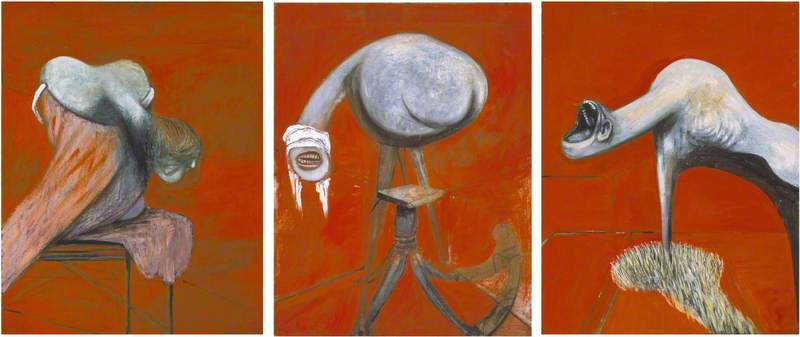

In the twentieth century, medicine and art merged in the figure of Henry Tonks. His drawings and pastels of soldiers with severe facial injuries in the First World War were concealed from public view as they were deemed bad for morale. Until very recently they had been quietly excluded from the history of that conflict, but were displayed in an exhibition at the Royal College of Surgeons in 2014.

In 2009, artist Jenny Saville portrayed a child with a facial port wine stain on a Manic Street Preachers album cover. Fearful of negative public reaction, four major supermarket chains concealed the 'offending' image.

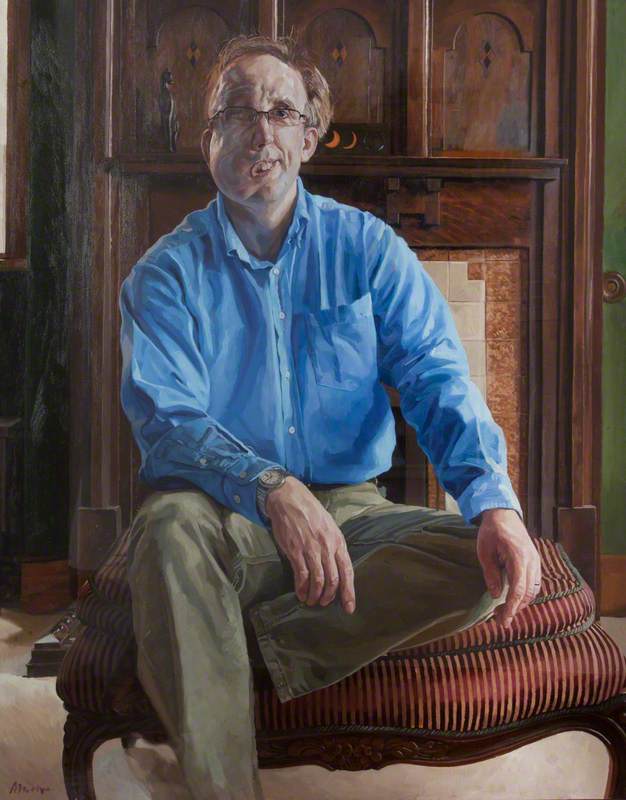

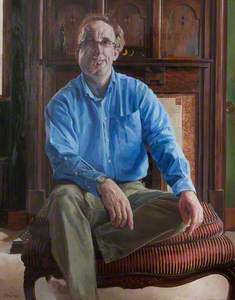

The charity Changing Faces opened a debate about art, aesthetics and disfigurement and three portraits of people living with facial difference were commissioned. One of these, Alastair Adams' powerful portrait of Marc Crank, is held by Girton College, University of Cambridge.

Mary Rose Rivett-Carnac, Art UK Copyright Officer