Once upon a time – in the Middle Ages, that is – the codpiece was nothing much to write home about at all. The best and the worst that could be said of it was that it was serviceable. Why? And what was it for anyway? Answers to these questions have to do with the way men's hoses were created back then. Each leg was separate. Consequently, there was nothing in the middle. What might serve then as a useful wind-break or draught-excluder?

A Legend of Saints Justus and Clement of Volterra

probably 1479

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494)

Something fairly crude and simple and triangular, came the answer, to protect the wearer from harm. Certainly nothing that might require the services of a tailor. So a triangle of cloth was fashioned, perhaps out of a piece of coarse linen. This was the codpiece, and its role was a protective one, to safeguard the precious honourable member from harm.

By the sixteenth century, everything had changed. The Tudor monarch Henry VIII was a power-dresser. He needed to impress all those European lineages which had been in existence much longer than the Tudors had – or would ever be. His attentions to the particular of dress – tilt of hat, many beringed fingers, shoulder pads, etc., etc. – was quite extraordinary – and much remarked upon at the time for its eye-catching splendour and its singularity. Amongst these adornments of Henry's was a codpiece, always. A rampant codpiece. A codpiece which testified to male bragadoccio. A codpiece which spoke of fertility. Alas, and as we are all, of course, aware, it was not to be. His only son, a sickly boy, died before he could procreate.

Henry VIII (1491–1547)

c.1540–1547

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543) (studio of)

Henry's codpiece is seen at its most rampant in various royal portraits of the monarch. One is at the Walker Gallery in Liverpool. A second is at the National Portrait Gallery in London, and it is of particular interest to this particular writer because the sight of it, hanging in the Tudor Gallery of sixteenth-century British portraiture, stirred into motion an entire book about the codpiece in art.

Henry VIII and Henry VII

c.1536–1537

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543)

That London portrait on view there today (online only at the moment) is a much-diminished version of its former self in so far as it is a cartoon upon which Hans Holbein the younger based a much larger painting. This painting suffered a calamity at the end of the seventeenth century. It was destroyed, like much else that was precious, in the fire which burnt the Whitehall Palace to the ground in 1698. Now only the cartoon survives by Holbein himself. A copy of the original by Remigius van Leemput, which he painted more than a hundred years after the original, lives at Hampton Court – there is also a version at Petworth House.

When I say that the cartoon is diminished, I mean that it is much narrower than the painting. It excludes, for example, two of Henry's hapless queens entirely. To lovers of codpieces, this is something of an advantage, as you will discover.

When I looked at it one Saturday morning a couple of years ago, I saw an unusually tall portrait in a dimly lit room which showed off two kings – and no one else. Henry VII stands behind his son, looking suitably ghostly. (He was, of course, dead by the time that Holbein made this likeness.) His son, also Henry, stands in front, hogging the limelight, looking a little like a stout tailor's dummy from which almost every bit of fashionable accoutrement known to a prosperous male in the 1530s has been hung. And foremost amongst these accoutrements is the splendid, snail-like codpiece, which seems to be positioned so centrally that it draws our eye to it irresistibly. Nothing is more important than me, it seems to be saying.

The Tailor ('Il Tagliapanni')

1565-70

Giovanni Battista Moroni (c.1520–1525–1578)

For around fifty years of that century, the codpiece thrived in European portraiture as never before or since. This was its moment. You can see it in great paintings by the likes of Giorgione, Titian, Moroni, Coello, Parmiginiano and many others. All these sitters (I mean standers because it is inconceivable that you might wish to be comfortably seated for long in a codpiece) are prosperous men of eminence in their fields, men of the church, men of court, men of aristocratic lineage, kings, emperors.

Amongst the few to paint codpieces worn by males of a lower social order was Brueghel. It took considerable wealth to commission a portrait, and such portraits were, generally speaking, very studied representations of the sitter, showing them exactly as they would wish to be seen in order to impress or overawe.

Two Peasants Binding Faggots

c.1620

Pieter Brueghel the younger (1564/1565–1637/1638)

What is interesting about these portraits is the attitude of the subject to the codpiece that he is wearing. To us, a codpiece looks outrageous, over-the-top, rearingly priapic, almost ridiculous in its claims. And yet it was seldom even remarked upon or written about at the time. Things were as they were.

What is more, the subject seldom seems to acknowledge the presence of the codpiece, as if the evidence here of outsize genitalia is scarcely even to be noticed. Instead, there seems to be a general attitude of studied unawareness, aloofness, or even indifference, as if there are far more important things in this world to be thinking about.

Henry VIII (1491–1547), Founder of Trinity College, Cambridge (1546)

c.1567

Hans Eworth (c.1520–after 1578)

What was it for then? To pull the girls? Not necessarily. Most likely it existed as living, eye-catching proof that this rich male was fecund, and could be guaranteed to produce as many male heirs as any poor female body could ever hope to cope with. Not so poor Henry, no matter how many wives needed to be sacrificed as he tried and he tried.

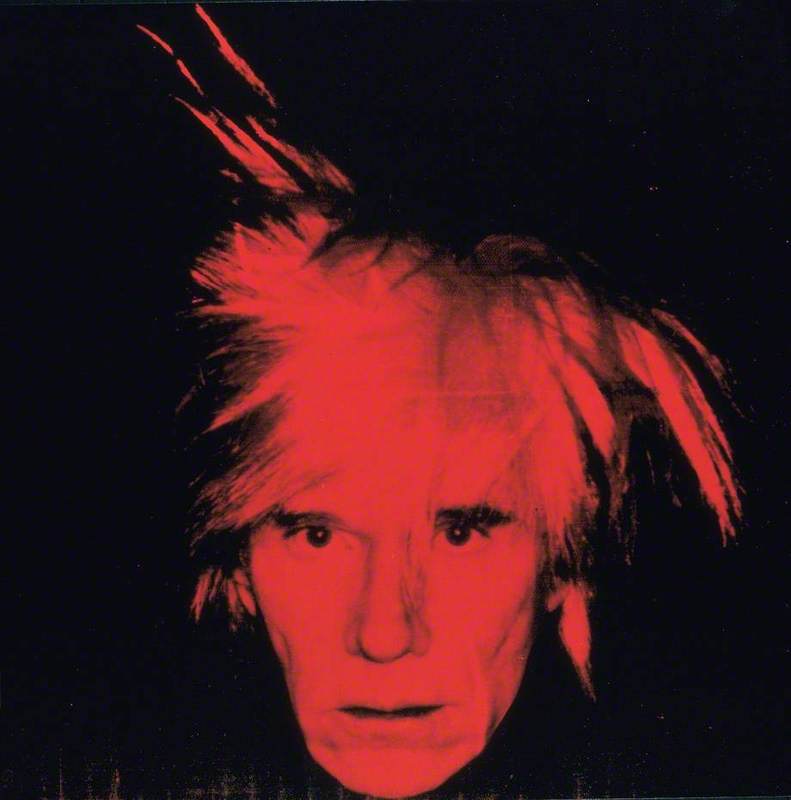

Michael Glover, poet, art critic and author

Michael's book Thrust: A Spasmodic Pictorial History of the Codpiece in Art, published by David Zwirner Books, is available now