Search Art UK for 'artist at work' and a small but intriguing group of paintings appear. Each of these shows an artist or groups of artists engaged in the act of creation. From the frank copy of a self-portrait of Elizabeth Vigee Le Brun seemingly interrupted at her easel, to the depiction of an artist in motion by Clifford Ellis, these works give us a sense, albeit romanticised, of the labour behind the painting in front of us.

No such contemporary depiction exists of Hans Holbein, who transfixed the early Tudor court with his talent, although in 1861 John Evan Hodgson imagined the artist pausing at his easel to show his portrait of Thomas More to his eminent sitter. We can still find Holbein at work, however, through a fascinating group of drawings which seem to have first joined the Royal Collection shortly after the artist's death in 1543.

Hans Holbein (c.1497–1543) was born in Germany and made his name in Switzerland. In 1526 he travelled to England in search of work at the Tudor court. His first patron in England was Sir Thomas More, the statesman and author, who commissioned two works from the artist (one of them the portrait which is the subject of Hodgson's imagined scene). Holbein quickly gained success in England, and his portraits became sought after among elite society. By September 1536, he had been appointed King's Painter, a salaried role which saw him paint portraits of Henry VIII, as well as at least three of the king's wives and two of his children.

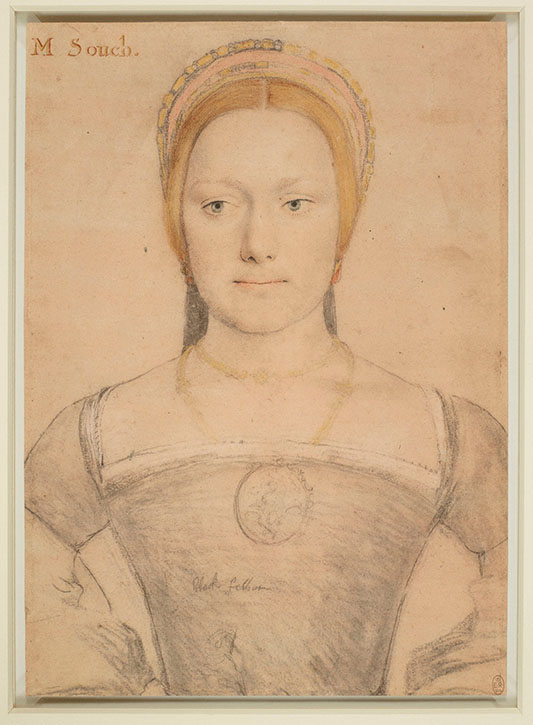

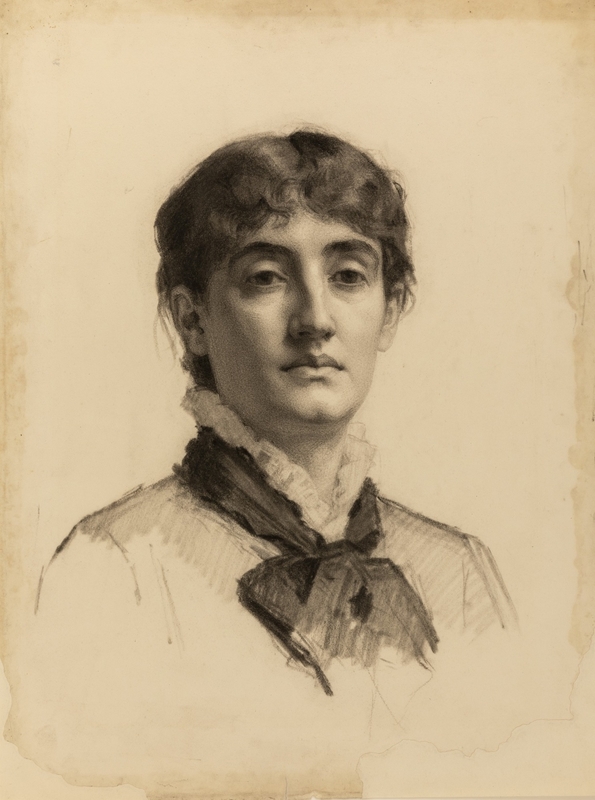

Holbein's portraits were based on careful preparatory drawings, and 80 of these, the majority of portrait drawings from his time in England, survive in the Royal Collection, alongside a group of paintings and miniatures. The identities of many of the sitters are inscribed on the drawings in an eighteenth-century hand, a copy of mid-sixteenth-century identifications. In some cases, such as Mistress Zouch and Lady Ratcliffe who appear below, these names could refer to more than one person, so we remain uncertain about the subject's exact identity.

The drawings were made by Holbein to record the likeness of his sitters and he sometimes also recorded details of costume or jewellery. In his drawing of John Poyntz, a mid-ranking courtier from Gloucestershire, he positioned his sitter with the head turned to look sharply upwards. We don't know what Poyntz was intended to be looking at (a devotional figure has been suggested), but the pose must have been difficult to hold for long. Holbein's rush to record what he needed is seen in the roughly sketched cloak he throws over Poyntz's shoulder, seemingly as a last-minute aide memoire before his sitter moves.

A similar quick reminder is found on the beautiful drawing of 'Mistress Zouch'. Over a bodice which he has recorded is 'black felbet' (or velvet), Holbein quickly sketched a flower for the sitter to hold in the finished painting.

Holbein sometimes used the blank spaces around his sitters to record details of their dress or ornaments. In the drawing of 'Lady Ratcliffe' he used both chalk and metalpoint to record the embroidered decoration of her bodice in the space between her shoulder and cheek.

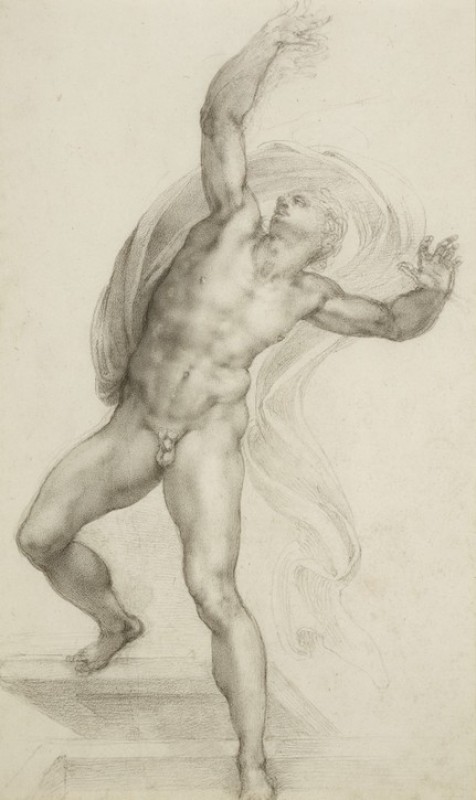

Charles Wingfield, who sat to Holbein with a perplexingly nude torso, wore a ring around a bracelet on his wrist, which is the subject of a separate study in a corner of the paper. Is he a pugilist, who has removed his ring to protect his fingers? So much about this drawing is uncertain.

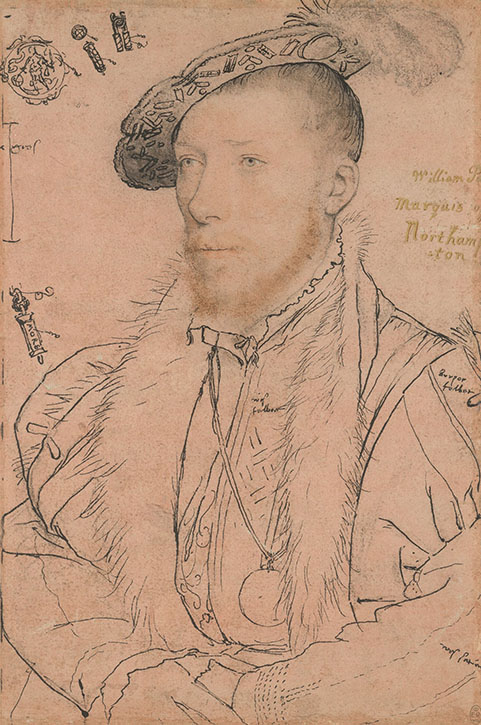

Less mysterious is the drawing of William Parr, brother of Catherine Parr (Henry VIII's sixth and final queen), whose surviving financial accounts in the National Archives show his love of the finer things in life. Holbein has not only drawn the sitter's magnificent clothes but recorded details of his hat badge and aiglets (or tags) as separate studies to the left of the sheet. A scale at the very left-hand edge must have served a practical function, but what this was is unclear as a crucial part of the inscription has been trimmed, most probably in the eighteenth century.

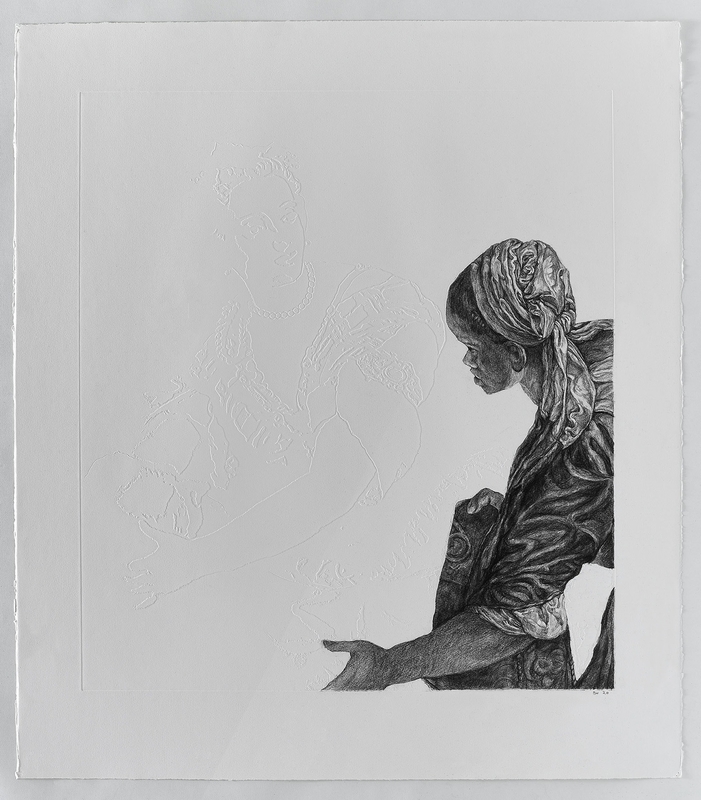

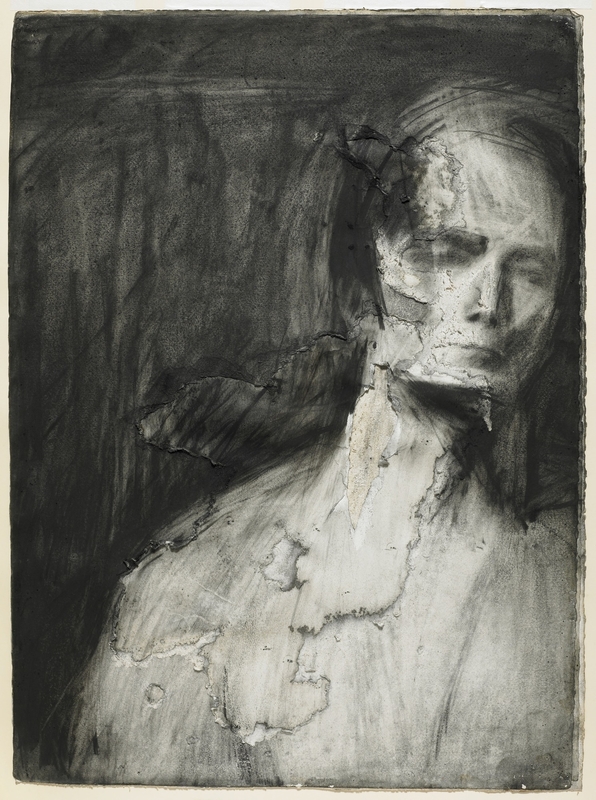

All of these details give us a glimpse of the artist at work, busily recording what he needed to create his final portrait. And nowhere do we get closer to looking over Holbein's shoulder than in two unfinished portraits, of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, and Mary, Duchess of Richmond and Somerset. Henry and Mary were the son and daughter of the powerful Duke of Norfolk, and were probably depicted by Holbein in late 1535 or early 1536. The finished portraits do not survive. In each case, Holbein has abandoned the drawing at an early stage, showing us what his sheets looked like part way through the process of recording his sitter's likeness.

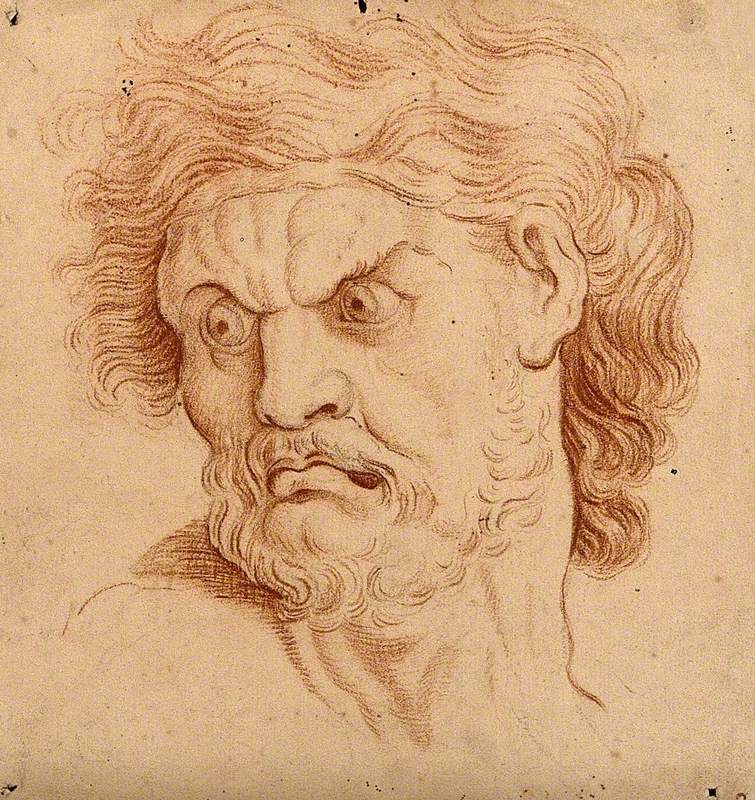

Take the drawing of the Earl of Surrey (who has been misnamed Thomas by the eighteenth-century copyist). Holbein has made this, like all his drawings after 1532, on a paper painted with a pink preparation. Over this, he has drawn outlines in tentative black chalk and then started to work up the details of his sitter's face. The earl's hair is very roughly coloured in brown chalk. We do not know why Holbein abandoned the drawing at this stage, but it seems most likely that he was dissatisfied with his subject's pose, as he turned the earl to face the front and started again, on a fresh sheet of paper.

This time he completed his drawing, and we can see how that rough brown chalk in the hair was intended as an under layer, over which Holbein placed meticulous strokes of black chalk to create a depth of colour and texture. He also firmed up the lines of the costume, and shaded in the sitter's cap to record the texture of feather and velvet (with sharp chalk lines to catch the threads joining the panels).

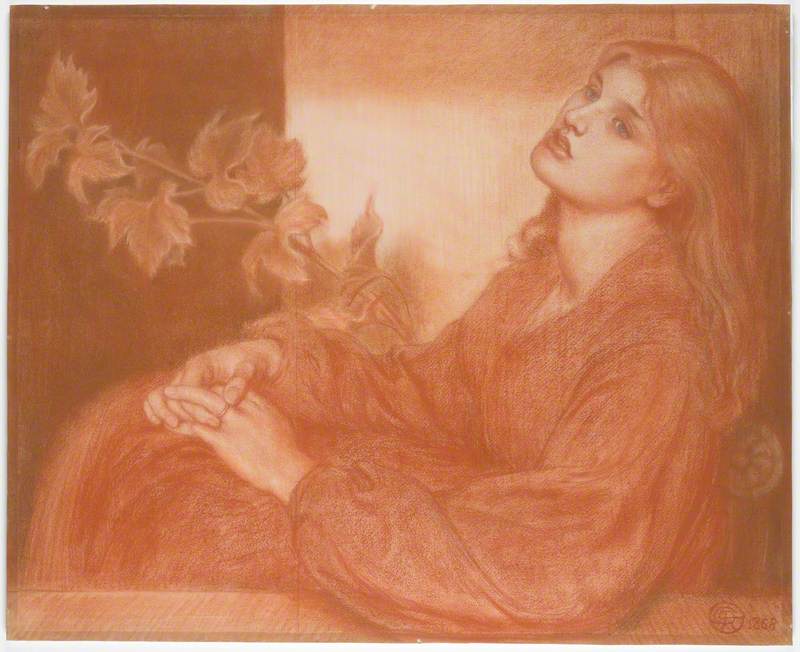

The drawing of the Duchess of Richmond, too, is unfinished, and Holbein has subsequently used the sheet to record the details of her cap ornaments: Ms and Rs for Mary of Richmond. Look closely, and you can see that the duchess is looking down while she is drawn. She is probably reading to pass the time, unconcerned by the presence of the artist at work.

The drawings discussed here are featured in the exhibition 'Holbein at the Tudor Court', on display at The Queen's Gallery, Buckingham Palace, until 14th April 2024. All the works by Holbein in the Royal Collection can be explored on the Royal Collection Trust website.

Dr Kate Heard, Senior Curator of Prints and Drawings, Royal Collection Trust

.jpg)