In Western Europe the ability of artists to paint realistically has been admired for a very long time. The Roman writer Pliny the Elder, writing in the first century AD, tells the story of the fifth-century BC Greek painter Zeuxis who painted a bunch of grapes so convincingly that birds flew down to peck at them.

No such Greek paintings survive, but some Roman wall paintings like those at Pompeii and Herculaneum have a similar ambition. Fragments of Roman frescoes in the Victoria and Albert Museum are examples.

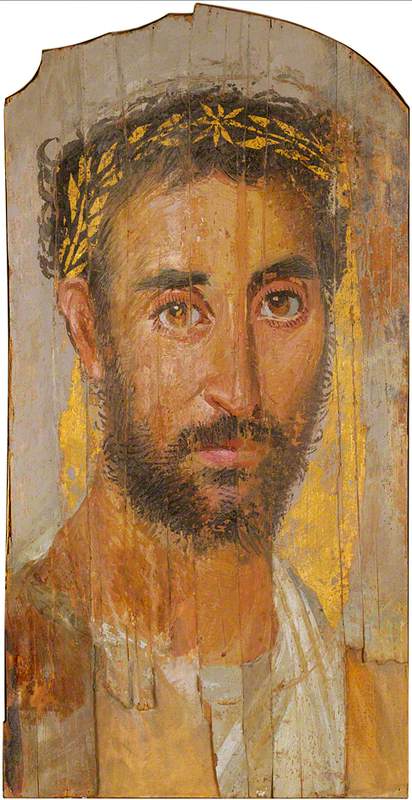

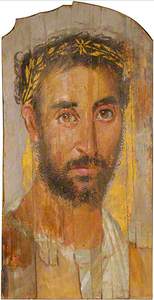

The remarkable portraits on the wooden cases of Egyptian mummies during the periods of the Greek and Roman occupations (about 300 BC to AD 600), such as this one in The National Gallery, also show how important realism was the painters and patrons of the period.

But realism has not always been important to artists. In different times, and in different cultures, there has always been a shifting balance between 'idealism' – painting an unrealistically perfect image representing an idea or a story – and 'realism' – seeking to accurately record the visual appearance of the world. Great art is full of ideas and meanings; how they are best expressed is forever changing.

Before the Renaissance of the fifteenth century for example, religious art, which was the main subject for artists in Europe, was intended to provide an emotional focus for worship and inspiration.

The Virgin and Child

about 1265-75

Master of the Clarisse Panel (active 1275–1300) (attributed to)

The painting stood for the saint or story depicted – it was not intended to be, and did not need to be, a lifelike representation. This is the tradition of the icon.

Perspective

However, changes in society and culture in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Italy encouraged a renewed interest in realism and the classical traditions of Greece and Rome. As part of this 'Renaissance' (literally meaning 'rebirth'), the theory and practice of perspective were perfected in fifteenth-century Florence by Brunelleschi, Alberti and others.

An understanding of perspective enabled artists to accurately create the appearance of three-dimensional spaces in their paintings. Their work could thereby integrate into the real architecture of the churches and chapels in which they hung or on whose walls they were painted, as seen in Lorenzo Costa's altarpiece.

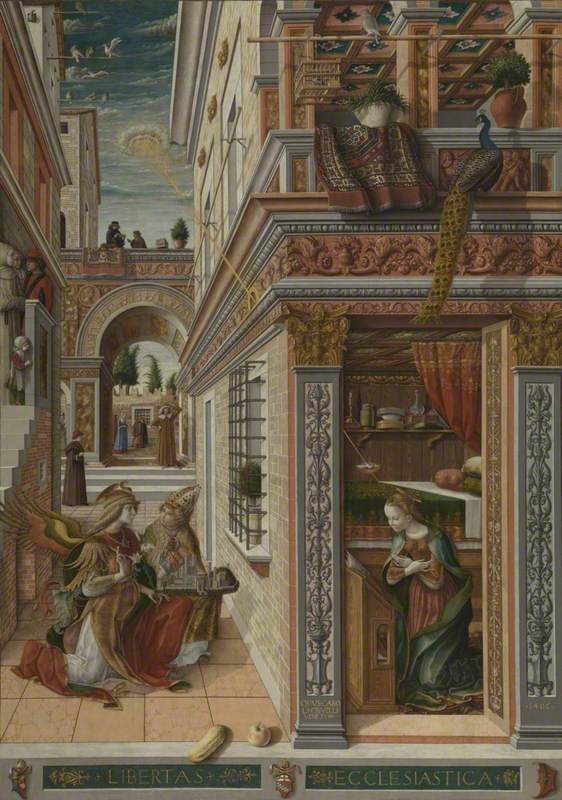

In Crivelli's Annunciation the artist shows off his mastery of perspective, and the trompe l'oeil details – the balcony at the top and the fruit in the foreground designed to trick the eye – add to success in creating three-dimensional space.

The Annunciation, with Saint Emidius

1486

Carlo Crivelli (c.1430–c.1495)

Large-scale decorative paintings often extend the architecture of the buildings they enhance and bring in landscapes and figures. The great canvases of the Venetians Tintoretto and Veronese are good examples. In a museum and out of their original context, however, they need to be seen from a particular angle for their proper effect to be appreciated. Veronese's Unfaithfulness is part of a series that was obviously meant to be seen from below and originally decorated a ceiling.

Similarly the interiors of domes were often painted with balconies and figures, and views of the heavens beyond. These were all intended to look convincingly real to the viewer.

Illusionistic Trelliswork Cupola with Disporting Putti

Giovanni da Udine (1487–1564) (attributed to)

The Creation of the Elements: Chronos and Cybele with Zeus, Hera and Poseidon

Paolo Veronese (1528–1588) (after)

Anamorphism

Anamorphism is a special development of perspective, in which an image is intended to be viewed from a particularly unusual angle, or reflected in a curved surface. The most famous example is the skull in Holbein's The Ambassadors, in which this symbol of the ambassadors' mortality is only revealed when the painting is viewed from the right, close to the canvas.

Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve ('The Ambassadors')

1533

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543)

These reminders that, however important or rich we are on earth, we all shall die, are quite common in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century art. What is curious here is that the message is both hidden and prominent at the same time.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, distorted images, which needed to be viewed in cylindrical or conical mirrors, became popular as curiosities, toys and demonstrations of the laws of optics, like this anonymous example in the West Highland Museum.

There are several more examples in the Science Museum.

Trompe l'oeil

In contrast to anamorphic distortions is the trompe l'oeil, the French for 'deceive the eye', which refers to a painting that is intended to trick viewers into thinking that they are looking at a real object rather than a flat painting of an object.

Pliny's story of Zeuxis shows how the ability to paint realistically has been valued for thousands of years. But the intention to deceive the viewer is something else. It does need skill and technical knowledge, but it can also be dismissed as superficial and a meaningless gimmick.

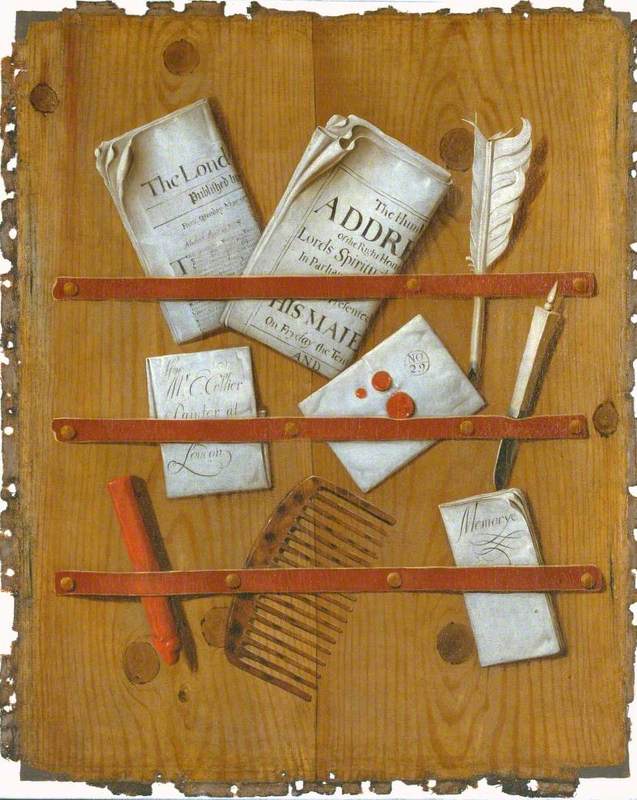

As the previous example of Crivelli's Annunciation shows, the use of trompe l'oeil as means of enhancing the reality of your subject was appreciated in the fourteenth century. Later it became an end in itself. Many seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish artists for example specialised in trompe l'oeil works, such as Gysbrechts and Hoogstraten.

Trompe l’oeil of a Framed Necessary-Board

1662/1663

Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678)

This particular type of subject matter, the 'letter rack', was also a speciality of Edwaert Collier in eighteenth-century England, who showed how the meticulous painting of random accumulations of day-to-day material could deceive the eye.

Trompe l'oeil, Letter Rack

c.1700

Edwaert Collier (c.1640–c.1707)

In portraits of the period the figures sometimes break free of their (painted) frames and project themselves towards the viewer.

A Girl with a Basket of Fruit at a Window

1657

Gerrit Dou (1613–1675)

Hoogstraten was also responsible for a rare peepshow, now in The National Gallery, in which a typical Dutch home, of the kind familiar from the paintings of De Hooch and Vermeer, can be viewed in three dimensions within a small box via two lenses in the sides.

A Peepshow with Views of the Interior of a Dutch House

about 1655-60

Samuel van Hoogstraten (1627–1678)

Hoogstraten needed a mastery of perspective and anamorphism to make it work. Vermeer certainly used optical equipment to ensure the complete accuracy of perspective in several of his interiors such as Young Woman Standing at a Virginal.

A Young Woman standing at a Virginal

about 1670-2

Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675)

The combination of technology and realism was enormously interesting to Dutch painters of the seventeenth century.

A little later, the Dutch eighteenth-century painter Jacob de Wit was one of several who specialised in decorative paintings intended to look like plaster sculptural reliefs.

These were often intended to be part of architectural schemes – above doors, for example.

Trompe l'oeil became very popular again in nineteenth-century provincial American art, as shown in the works of William Michael Harnett.

Although not taken seriously by art historians until recently, such paintings celebrate the lives and concerns of ordinary Americans.

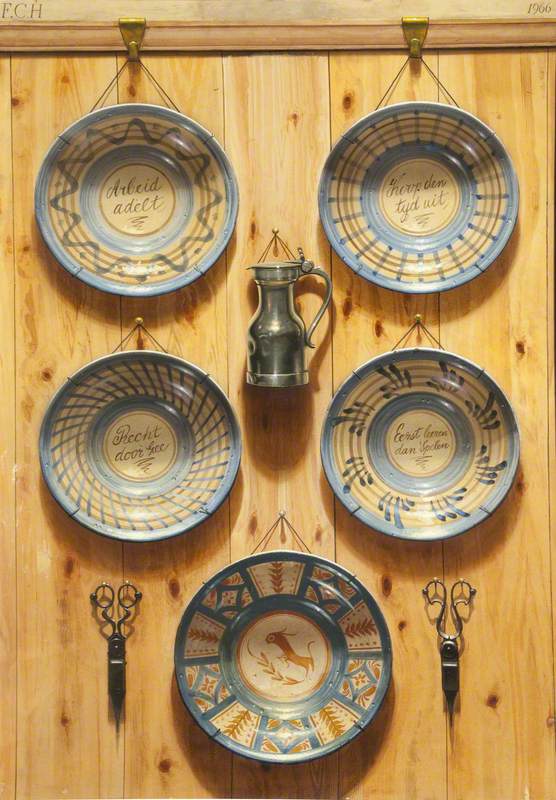

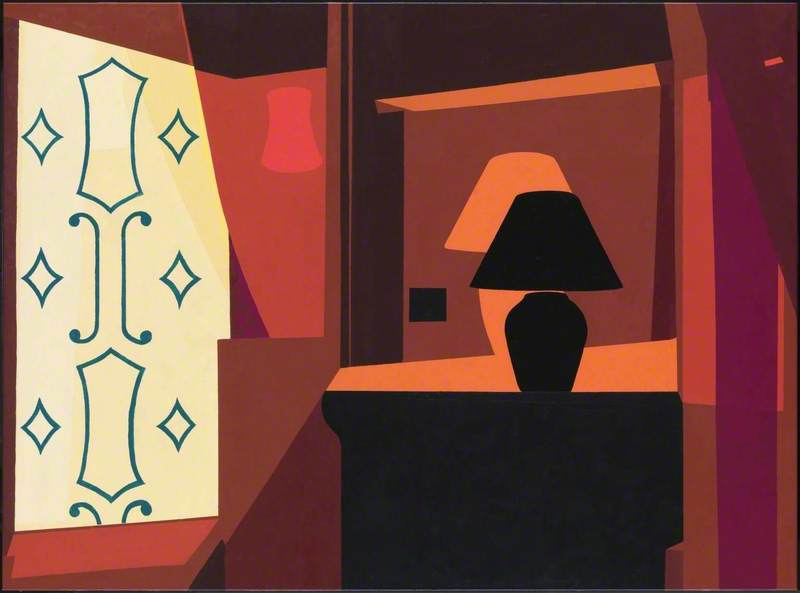

Trompe l'oeil has even had some followers in the twentieth century, for example Frederick Clifford Harrison and the anonymous painter of this country-house cupboard.

A Trompe l'oeil of China and Glass in a Cabinet

early 20th C

British School

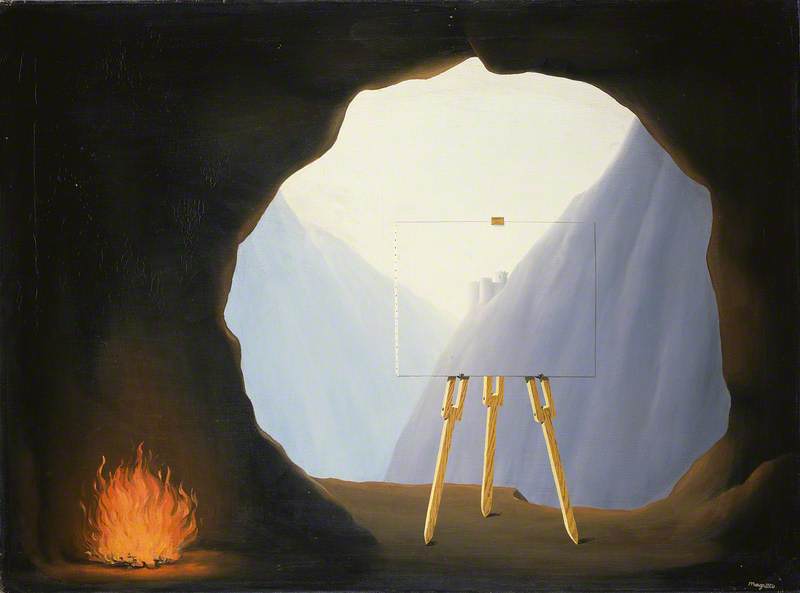

Also exploring the boundaries between art and reality were artists of the Surrealist movement, interested in the worlds of imagination, dreams, and alternative realities.

Tanguy painted totally imaginary scenes in a hyper-realist manner to create visions of alternative worlds and René Magritte plays with the artist's ability to depict and deliberately confuse illusion and reality.

The greatest artists always tell us something about the world we inhabit, whether eternal human emotions that we all recognise or deep intellectual ideas. But in the first instance they must engage our eyes through their skill in creating images that make us stop, admire, and then think.

Andrew Greg, National Inventory Research Project, University of Glasgow