In this series, 'Conservation in focus', Simon Gillespie, Director of Simon Gillespie Studio, explores the art of conservation. In each article, Simon looks in depth at a particular technique or tool that is crucial to conservators and explores the challenges – and triumphs – associated with their everyday work.

X-ray

An x-ray image will sometimes give fascinating insights into what is going on underneath the visible paint layers. X-rays pass through certain materials – including most pigments – but are obstructed by others such as lead and mercury (which are used in pigments such as lead white and vermilion respectively): these will show up white on the x-ray image. Any nails in a painting's support will also appear, being made of metal. Sometimes, pentimenti (areas where the artist has changed their mind about an element of the composition) that are not visible to the naked eye can sometimes be seen in an x-ray.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Simon and Bendor Grosvenor with the Rubens

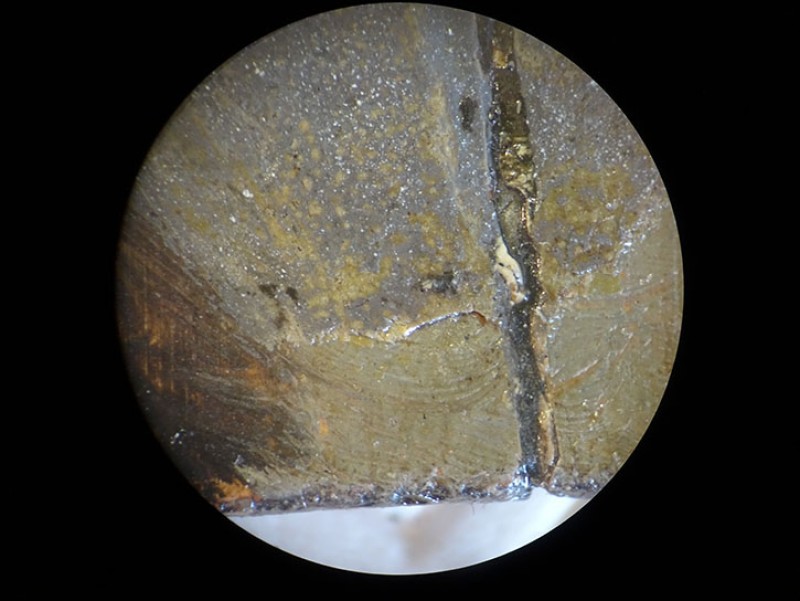

The x-ray carried out on the portrait of George Villiers revealed that the ground layer (which is applied by the artist onto the panel as a preparation layer before the paint is added) had been applied with a broad brush leaving distinctive streaks. This type of imprimatura (another word for the ground layer) is characteristic of Peter Paul Rubens and therefore supported our theory that the portrait was the original lost Rubens.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

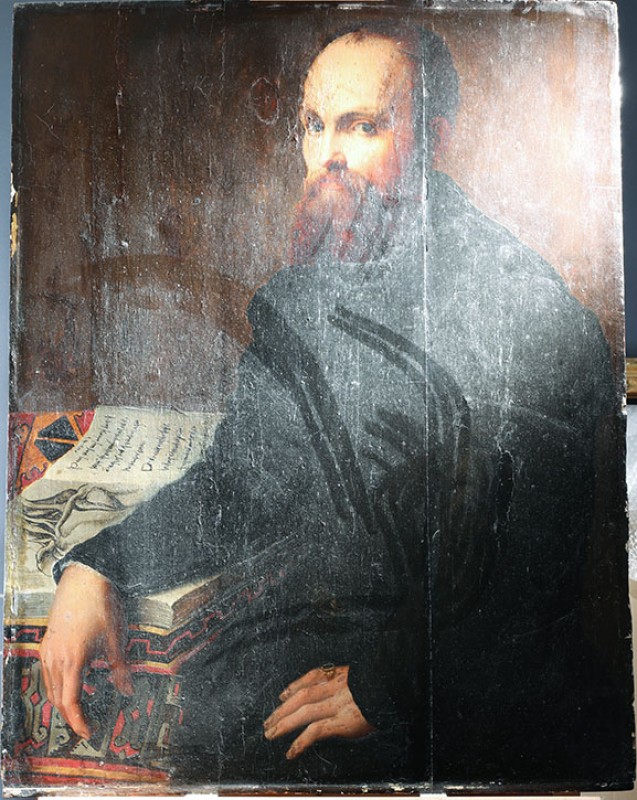

George Villiers (1592–1628), 1st Duke of Buckingham 17th C

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

Glasgow Life Museums

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Self Portrait at the Age of 22 c.1623–c.1629

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) (studio of)

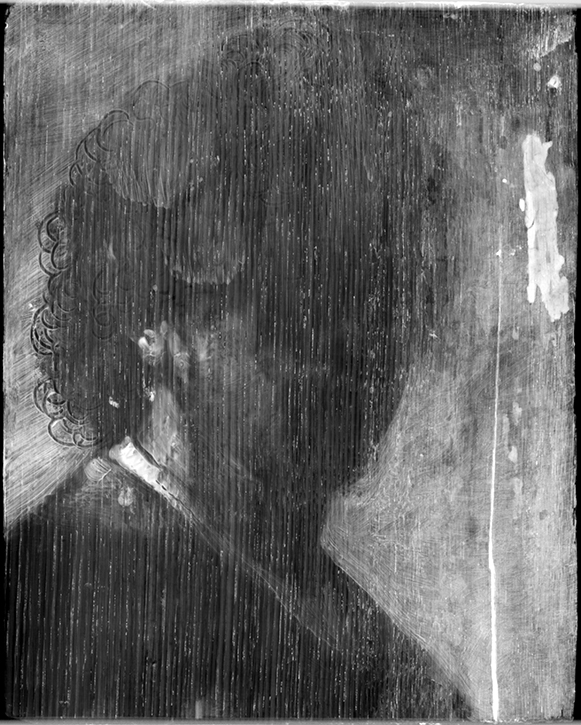

National Trust, Knightshayes CourtX-rays can be hard to interpret, however. In the case of the Self-Portrait aged 22 from Knightshayes Court, which was brought to my studio for treatment in the hope that it might be positively attributed to Rembrandt, the x-ray evidence was disputed.

It is known that Rembrandt usually painted the background in first, leaving an unpainted area called a 'reserve' for the head to be painted in afterwards. The reserve is visible in x-ray images of Rembrandt's paintings.

Image credit: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Self Portrait

c.1628, oil on panel by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

The version of this portrait at the Rijksmuseum is the one that has been accepted since 1959 as Rembrandt's original, and the x-ray image showed that this version has a larger reserve than the final size of the head. To the late Ernst van Wettering, then the expert on Rembrandt, this proved that the artist hadn't yet decided how to place the head: evidence of the artist working out his composition. Conversely, argued Van Wettering, in the Knighsthayes version and another version at Kassel, the reserve is the same size, which shows that the artist had already decided what size the head would be. He concluded that these two portraits are copies made after the Rijksmuseum prime version.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

An x-ray image of 'Self Portrait at the Age of 22'

c.1623–c.1629, oil on panel by studio of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669). National Trust, Knightshayes Court

However, Bendor, looking at an x-ray taken of the Knightshayes Rembrandt, has shown that the area of the reserve does not closely follow the outline of the face, and therefore does suggest the artist working out his composition. Who is right? In the end, we were only able to get the painting attributed to Rembrandt's studio – better than what it was listed as originally, but not the full attribution to the artist we had hoped for. Perhaps further research in the future will change this.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studios / Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Virgin and Child with a Pomegranate c.1500

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510) (studio of)

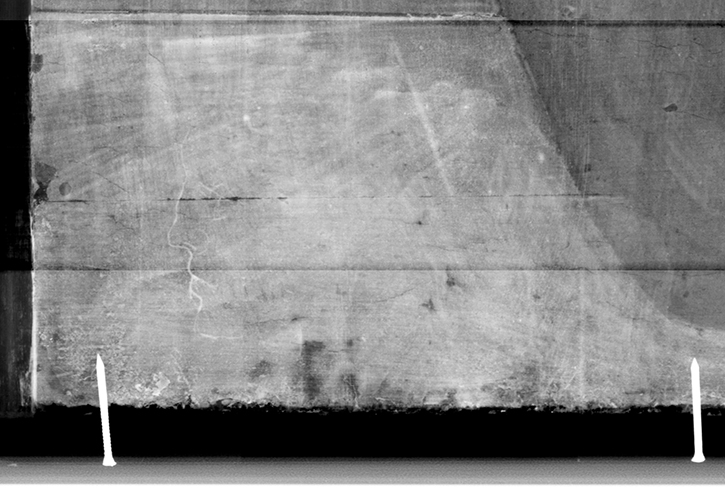

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesSometimes an x-ray produces an amazing surprise: when we carried out an x-ray on Virgin and Child with a Pomegranate from the National Museum of Wales, we were mostly interested in seeing the extent of any damages under the existing paint layer.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

An x-ray detail of a doodle in the bottom-left corner of the Botticelli panel

I was absolutely thrilled, when zooming in to the high-resolution image produced, to see revealed a secret kept hidden for over 500 years: underneath the paint layers was a carbon (pencil) drawing showing the profile of a man's head – a doodle almost certainly by Botticelli before the paint was applied in that area. No one had seen this doodle since Botticelli or one of his assistants painted over it 500 years ago. This is a wonderful example of how modern technology enables us to reveal aspects of a painting that are impossible to see with the naked eye and have therefore been hidden for centuries.

Carrying out an x-ray of the portrait of a lady by Joshua Reynolds from Glasgow Museums also gave us a surprise: while the current composition shows the figure with her arms down by her sides, the x-ray showed that the artist had initially painted her with her left arm raised up so that her palm supported her cheek.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

X-ray of 'Unfinished Portrait of an Unknown Lady'

c.1770, oil on mahogany panel by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792). Glasgow Museums

Infrared

Infrared also allows us to see underneath the final paint layers, picking up different things to what an x-ray might pick up. It is especially good at showing carbon drawing lines, and can therefore show whether the artist made an initial sketch beneath the paint layers and reveal instances where the artist changed their mind between sketching and painting.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Joos de Momper the younger (1564–1635) and Jan Brueghel the elder (1568–1625) (workshop of)

Birmingham Museums TrustWhen the painting Autumn – by Joos de Momper and the workshop of Jan Brueghel the elder – first arrived at the studio from Birmingham Museums as two dark, dirty, overpainted planks of wood, we took an infrared image to help us see through the murk. The image helped us to understand elements of the composition we could expect to find under the overpaint, such as showing the outline of the rocky outcrop that was completely concealed to the naked eye. It also showed us the artist's exquisite drawing lines, characteristic of Brueghel in their expressiveness. The screw of a cider press is conveyed in brisk diagonal lines, the figures are beautifully handled.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

'Autumn', detail of barrels in normal and infrared light

1605–1610, oil on oak panel by Joos de Momper the younger (1564–1635) and workshop of Jan Brueghel the elder (1568–1625). Birmingham Museums Trust

Similarly, in the first season of Britain's Lost Masterpieces, the preparatory drawings we saw in infrared images of the Spring and Winter paintings from Ulster Museum by Peter Brueghel the younger were typical of the artist, with short, one-centimetre-long interrupted lines rather than a continuous line.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Infrared image of 'Spring'

1633, oil on panel by Pieter Brueghel the younger (1564/1565–1637/1638). Ulster Museum

In the case of the Botticelli from the National Museum of Wales, the infrared revealed not only drawing lines but also showed that the artist had made numerous changes in areas, including the hands, proving that the painting was not a simple copy.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Infrared detail of the Madonna's hand, showing a change in the position of the index finger

With the panel by Joos van Cleve from Brighton & Hove Museums, art historian Micha Leeflang told us that we should look out for the artist's underdrawing style, as he used lots of hatching lines.

Viewing the Balthazar panel under infrared, drawing lines were visible: soft streaked lines indicated the elements of shading to be painted, for example, on the left sleeve of the velvet coat, the shirt, the legs and the ground at the bottom of the composition. There were also straight lines sketching the edges of the sceptre, the golden cup and the sword.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Infrared image of 'Balthazar'

c.1520, oil on canvas by Joos van Cleve (c.1485–1540 or 1541). Brighton & Hove Museums

The infrared image also showed evidence of pentimenti, where the artist had changed the composition during the process of painting: for example, the artist had originally placed Balthazar's sceptre lower on his shoulder, the feather on his hat had also been moved, and a shoulder strap across the figure's chest had been removed. The short skirt was initially drawn as a sort of Roman military belt made up of leather strips, called cingulum militare, which when it came to painting, the artist instead went with the pleated design we see today.

Image credit: Simon Gillespie Studio

Infrared detail of the skirt in the Joos van Cleve panel

In the next article, I will describe how analysing the paint itself can us help to understand a painting's history, including when and where it may have been produced.

Simon Gillespie, Director at Simon Gillespie Studio

Previous: My favourite tool: an ultraviolet torch