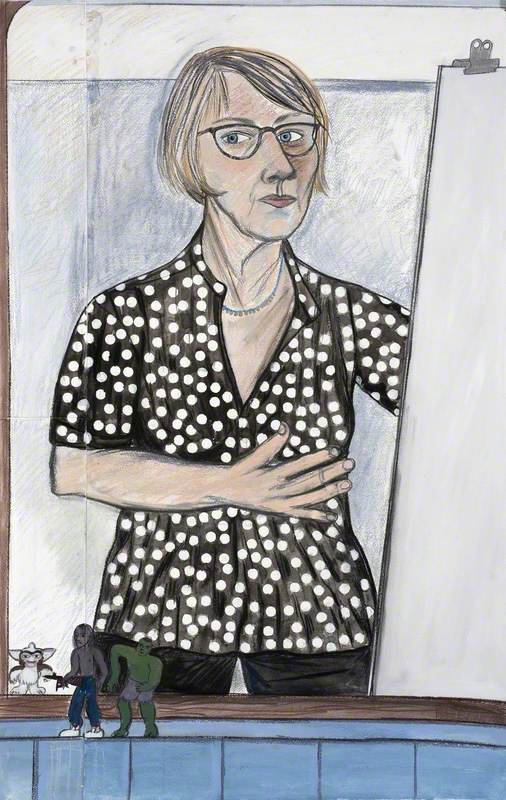

In 2018, Tate acquired a rarely seen self-portrait by Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872), one of Britain's most successful female artists. Painted in her late middle age, the self-portrait shows Carpenter as a proud and confident woman at the pinnacle of her career. Her sense of professional satisfaction was understandable given that she had been running a thriving portrait practice since the age of 20.

By the end of her career, she had exhibited no fewer than 156 pictures at the Royal Academy and seen her work acquired by public collections. Recognition was ever-present during her life, but has been sadly absent since her death.

Self-Portrait

1817, drawing by Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872)

Born Margaret Sarah Geddes in Salisbury, she was a largely self-taught artist who honed her talents by copying Old Masters in the collection of Lord Radnor at Longford Castle. As a generous supporter, Lord Radnor financed her move to London where, from 1813, she lived and worked independently.

In 1814, aged just 21, she exhibited at the Royal Academy for the first time. Three years later she married William Hookham Carpenter, who became Keeper of Prints and Drawings at the British Museum. They had eight children, three of whom died in infancy. She now had to balance motherhood with being a professional artist, and yet she continued to fulfil commissions and exhibit at the Royal Academy and the British Institution.

William Hookham Carpenter

1816

Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872)

The overriding influence upon her work was Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830), whose strident portraits were hugely fashionable throughout the Regency era. Matching Lawrence's complex painting style was no easy feat, but one which she achieved in every way. Her portrait of Henry Hoare, for example, has the same swaggering confidence that Lawrence had made so popular.

After Lawrence died unexpectedly in 1830, Carpenter was widely considered to be his natural successor. She seems to have embraced this challenge with her usual unshakeable confidence.

Her full-scale portrait of Ada King, Countess of Lovelace, who was Lord Byron's daughter and a gifted mathematician, received great praise when it was shown at the Royal Academy in 1836.

Ada King (1815–1852), Countess of Lovelace, Mathematician, Daughter of Lord Byron

1836

Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872)

Although the painting won the admiration of critics, Lovelace herself quipped: 'I conclude she is bent on displaying the whole expanse of my capacious jaw bone, upon which I think the word Mathematics should be written.' The historical value of Carpenter's portrait of Lovelace cannot be overstated; it is essentially the coming together of two of Britain's most gifted and independently minded women of the nineteenth century.

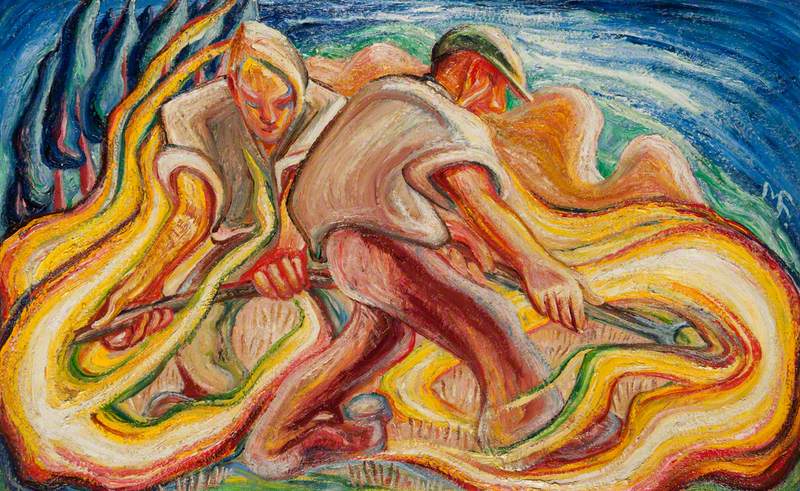

While Carpenter proved to all that she could paint on a grand, almost imposing scale, she also created small and intimate paintings such as The Sisters (1839).

This charming work depicts her two daughters looking over a folio book. At this point in her career, Carpenter was keen to demonstrate that her paintings offered not only anatomical accuracy and physical likeness, but also conveyed an emotional quality.

A rich source of patronage for Carpenter was Eton College. She painted several 'leaving portraits' of young men having completed their studies. This series began around 1760 by a headmaster who selected distinguished pupils to leave their likeness with the College instead of the usual leaving fee.

These portraits were painted fairly rapidly and Carpenter knew that they were unlikely to be exhibited publicly, therefore allowing her a greater stylistic freedom than her regular commissions. This is most evident in her 1841 portrait of Henry Beilby William Milner. The free and fluid brushwork is ideally suited to capturing the energy and freshness of the youthful subject.

In 1844 she was nominated for election to the Royal Academy but was unsuccessful. Being the only woman among 60 candidates meant her chances were slim. Gentleman's Magazine wrote some years later that she 'would certainly have been a Royal Academician but for her sex.' Despite not achieving Royal Academician status, she was greatly admired by her peers. This is evident from the number of artists whose portraits she painted.

The first and arguably most important of these was her portrait of the short-lived Richard Parkes Bonington, which was probably painted posthumously but based on an earlier sketch from life.

Richard Parkes Bonington

c.1827–1830

Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872)

She records Bonington as rugged and handsome, his direct gaze suggesting a confident personality no doubt buoyed by his early success as a painter. Ever the perceptive artist, Carpenter gives him a slight frown, thereby endowing him with a convincing note of brooding romanticism.

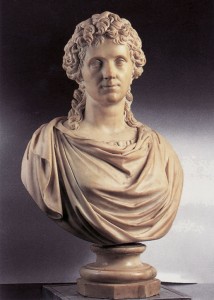

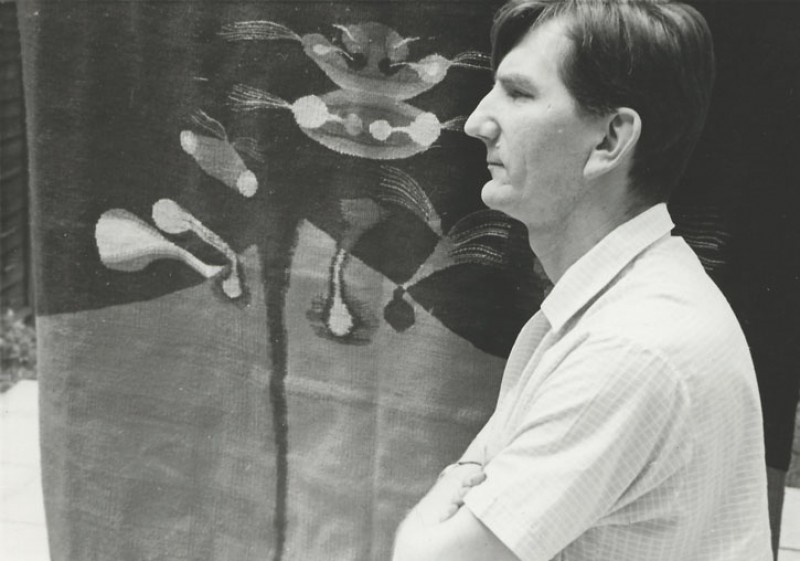

Around thirty years later she painted a portrait of the celebrated sculptor John Gibson.

He and Carpenter were almost the same age and had both achieved great success in their artistic careers. He had been a pupil of Antonio Canova in Rome and was widely considered one of the leading Neoclassical sculptors in Europe.

From 1852 to 1866, Carpenter resided at the British Museum where her husband worked. It was here that she found a new clientele of distinguished sitters. Her portrait of Sir Henry Ellis, principal librarian and director of the Society of Antiquaries, is testament to the warmth of character for which her paintings were regularly praised.

Sir Henry Ellis (1777–1869), Principal Librarian (1827–1856)

Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872)

Ellis was described as 'genial and kind-hearted', personality traits Carpenter has convincingly expressed. Her portraits of Gibson and Ellis were both displayed at the Royal Academy in 1857, the same year she was included in the hugely successful 'Art Treasures' exhibition in Manchester.

After the death of her husband in 1866, she largely retired from art and was awarded a pension of £100 by Queen Victoria. In many ways, she can be regarded as the last great British portraitist prior to the common use of photography. She sat for her own photographic portrait in 1862, a copy of which is in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

Margaret Sarah Carpenter

1862, albumen carte-de-visite photograph by Henry Webster

The extraordinary career achievements of Margaret Sarah Carpenter are all the more impressive given that she was following in the footsteps of major heavyweight portrait painters such as Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough and Henry Raeburn. Yet she was never daunted by the success of her predecessors or the competition of her male contemporaries.

Today she remains an unduly neglected figure, but the ongoing reassessment of women artists in art history will hopefully restore the reputation of this forgotten but formidable talent.

Jonathan Hajdamach, independent art historian

Further reading

Richard J. Smith, Margaret Sarah Carpenter (1793–1872): A Brief Biography, Salisbury & South Wiltshire Museum, 1993

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.