Giorgione is a hero of mine. He changed the course of art. He painted in such a revolutionary way that the 'Venetian greats' of the sixteenth century – Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese – would not have come to be without him. Had he not died so early on in his career, at the age of 32 or 33, I feel certain that his name would be as familiar to us as Michelangelo's and Leonardo's.

Self Portrait as David

c.1508, oil on canvas by Giorgione (1477–1510)

He was working at the same time as them. Leonardo was 25 years his senior, Michelangelo four. In Italy, Bellini, Titian and Raphael were also vying for commissions then, whilst Albrecht Dürer, Hieronymous Bosch and Matthias Grünewald shared the stage in northern Europe. Ever since my art college days, when I first looked into the history of painting, it has pained me that he is not more famous, that he is almost never the first to come to mind when we think of that, utterly seismic period of what we now call 'The High Renaissance'.

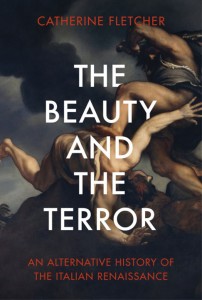

In the end, I have taken matters into my own hands and written a novel, The Colour Storm, about the artist, his importance, and what I imagined might have taken place in the last month of his short life, before he caught the plague – almost certainly – and perished. In the novel, Giorgione is searching for a new colour which just arrived in Venice, as all rare pigments invariably did, a colour 'more ravishing than even ultramarine', one that could make him famous for all time. Unfortunately for him, and the driver of the novel, every other famous painter I have listed above is also on the hunt.

'The Colour Storm' by Damian Dibben

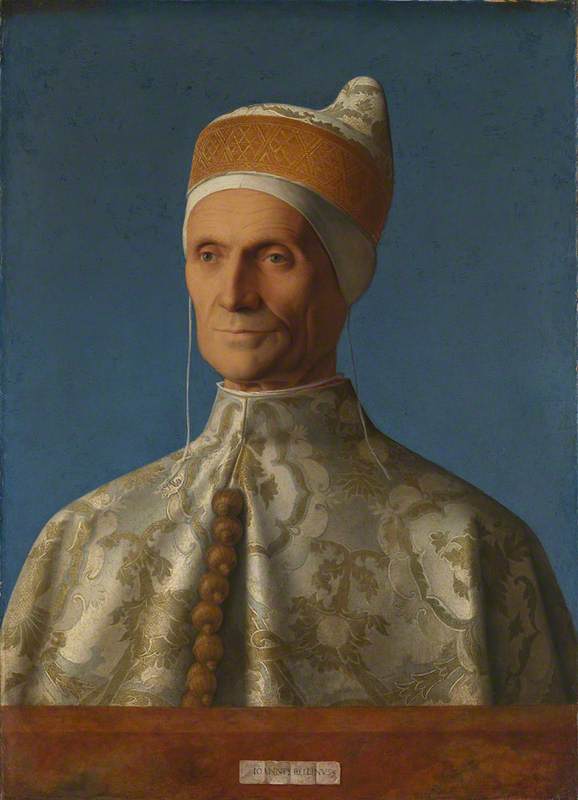

Little is factually known about Giorgione. His actual name was Giorgio Barbarelli and he came from the modest town of Castelfranco in the Veneto, 25 miles west of Venice. He headed to the city, probably as a boy, to apprentice in the super-productive studio of the Bellini brothers, Gentile and Giovanni. They were the most famous painters in Venice. Giovanni, in particular, was one of a new breed of supreme colourists in Italy. His portrait of the Doge Leonardo Loredan, in The National Gallery, is a study in sumptuous colour. Once seen, the vivid blue background and the greens and golds of Loredan's mantle can never be forgotten.

Venice was the richest place in Europe, in the world. It was the centre of global trade, the eye of the needle through which all the treasures of the east, from Persia to China – silk, china, spice, as well as pigments – all threaded first. Not just goods: ideas, science and new philosophies landed first in Venice. The city would have been awash with new ways of thinking, as well as being a cultural mixing pot like no other. There were dozens of printing shops also. Invented 40 years before, print had come into its own. Books, which had existed in their hundreds, were now being put out in the millions. All of this would have electrified the mind of the young Giorgio Barbarelli.

Self Portrait

c.1508, oil on canvas by Giorgione (1477–1510)

What else do we know about him? He was tall, hence his nickname, Giorgione meaning 'big George', and quite probably striking, if a painting of his in Budapest's Museum of Fine Arts is indeed a self portrait. At the age of 24, having probably set up his own studio, he too painted the doge, as well as a stunning altarpiece in his hometown's cathedral. A final notable fact is that he tutored and helped launch the career of a young artist, Tiziano Vecellio, more commonly known to us as Titian.

As it says in my novel, 'Titian had the luck of a long life, luck all the way through it.' And he, more than anyone else, is responsible for Giorgione being put in the shade of history. 'First student, then collaborator, then victor', the 80-year-old Bellini drily comments in The Colour Storm. When Titian was just 22, almost certainly still working for Giorgione, he unveiled his portrait of a man with a quilted sleeve, Portrait of Gerolamo (?) Barbarigo, now in The National Gallery. It is an astonishing calling card to the world: that giant, Prussian blue sleeve seeming to break through the fourth wall of the picture. Giorgione would die the year it was unveiled, whilst Titian would take everything he learnt from his master and pour it into a career that would endure another 65. Phenomenally talented for sure – but still lucky.

So what did Giorgione actually change? How did he manage to give rise not only to Titian, but to Veronese and Tintoretto and every genius that they in turn inspired? A visit to see Il Tramonto (The Sunset), his only significant painting in the UK, again at The National Gallery, will begin to tell us. Firstly, like La Tempesta, which is on show in The Accademia in Venice, the picture is first and foremost 'a landscape'. This was a new idea, all but invented by Giorgione in many people's opinion. The tree in the centre of the canvas, the receding valley and the blushing sky behind it are the star 'characters', whilst the three humans, one half hidden in a cave, appear almost secondary.

La Tempesta (The Tempest)

c.1505, oil on canvas by Giorgione (1477–1510)

La Tempesta is the same. The real draw of the canvas is the turquoise summer sky riven by a bolt of lightning. The picture also contains three humans – a soldier, a nude woman and her infant – and in both paintings none of the figures are obviously identifiable. They're not characters from the Bible, or from mythology, or from public life, the subjects of just about every other painting of the time. Instead each figure is mysterious in itself and even more curious as a group. Because of the mystery, we're invited to create a narrative for ourselves and use our imaginations, an act that draws us deep into the world of the painting.

And what believable, entrancing worlds they are. As well as inventing the notion of a landscape, Giorgione also gives us 'impressionism' for the first time, 350 years before Monet and Renoir. The Florentine school of painting – by which I broadly mean Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael – had just one, true focus: man, or woman. They started from the soul of a person and drew out. The human form, the body, muscle, sinew, mass. Those artists strove to bring alive skin, weight, the gaze of a person's eye, and the texture of hair.

Portrait of a Woman inspired by Lucretia

about 1530-2

Lorenzo Lotto (c.1480–1556/1557)

Giorgione, and his Venetian contemporaries – not just the Bellinis, but Lorenzo Lotto and Sebastiano del Piombo and many more – did the same, of course, but I believe their starting point was different. The atmosphere came first: the hour of the day, the time of year, the weather, the light, the feel of the sky, and the land. They wanted to create a mood-scape in which their characters would find themselves, an ever-changeable land, sea and sky that would bring those people to life in thrilling new ways.

The 'Gattamelata' (Man in armour with a squire)

1501–1502, oil on canvas by Giorgione (1477–1510)

Even Giorgione's paintings that are closely focused on their human subjects, such as his painting of a knight and squire in The Uffizi, Florence, and the similar Portrait of an Archer in The Scottish National Gallery (though this may be the work of a follower, not Giorgione himself) are suffused with mood. In the second portrait, every detail, from the way daylight catches on the surprised face of the archer, to the reflection of his hand in his breastplate tells us of the 'feeling' of the place before anything else.

The final thing and perhaps greatest thing to note about Giorgione and his Venetian counterparts was their use of colour. It's said in my novel, 'whereas the Florentines started with line, the Venetians began with colour.' This was to be expected, perhaps. Lapis lazuli, the star mineral of the age, arrived on the quays of Venice first, along with precious rocks from all over the world, all with remarkable hues locked inside them. But there was not just this practical element: Venice, more than anywhere was a riot of colour, of texture and surface, a place of never-ending pageants, pomp and theatricality. This was mirrored in everything from the glass made in Murano to the fabrics that were unloaded at the quays and turned into astonishing clothes.

Look again at the gown of Lorenzo Loredan, the intricate pattern, or Titian's giant bruise-coloured sleeve or Giorgione's juxtaposition of blue horizon against apricot sky in Il Tramonto – and you can almost see the path to the twentieth century, to Matisse, Kandinski and Rothko – and the very beginning of abstract art.

Damian Dibben, author

Damian's book, The Colour Storm: The Compelling and Spellbinding Story of Art and Betrayal in Renaissance Venice, is available from Penguin