In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Born in Thessaloniki, Greece, the Slade graduate Sofia Mitsola imbues her vivid and provocative works with tales of enchantment, deriving from Greek mythology and Eastern superstitions, while referencing her encyclopedic knowledge of cold-blooded reptilians and reflections on the intricate power dynamics of the 'gaze.'

Her solo show at Pilar Corrias 'Aquamarina: Crocodilian tears' reveals a natural progression from her previous body of work, a continuation of one evolving narrative – or myth – that invites the viewer to dive into Sofia's aquatic and otherworldly universe, manifested in amorphous and surreal forms on canvas.

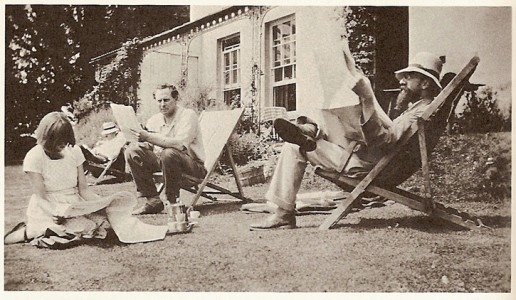

Sofia Mitsola

2020, photograph by Mark Blower

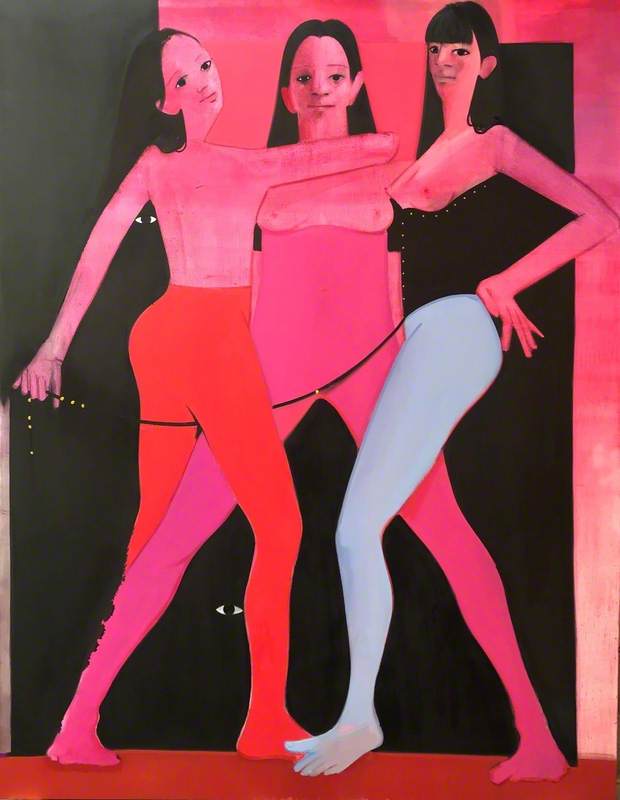

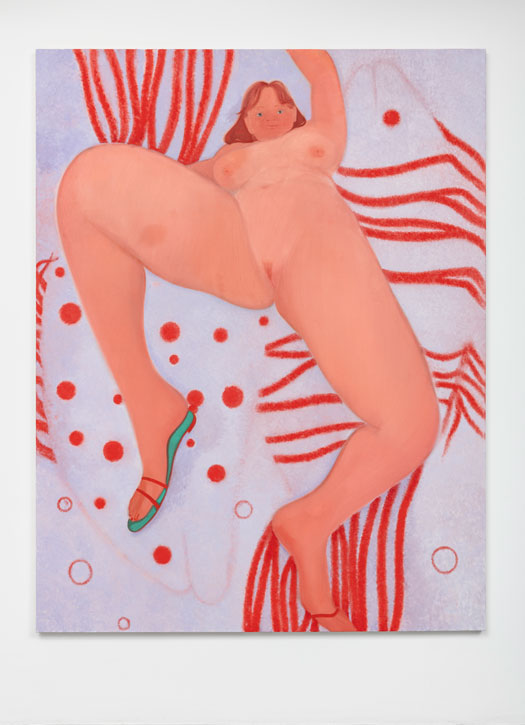

In dialogue with the gaze, the female body is a central motif in Sofia's work, one that is used as a metaphorical and visual device that both seduces and deceptively challenges the viewer.

I spoke to the artist ahead of her solo show, discussing all things from her inspiration from the sea, to her studio rituals. Scroll down to read the full interview.

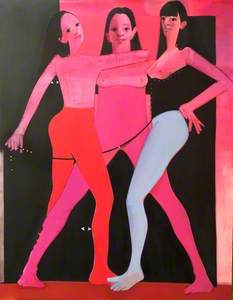

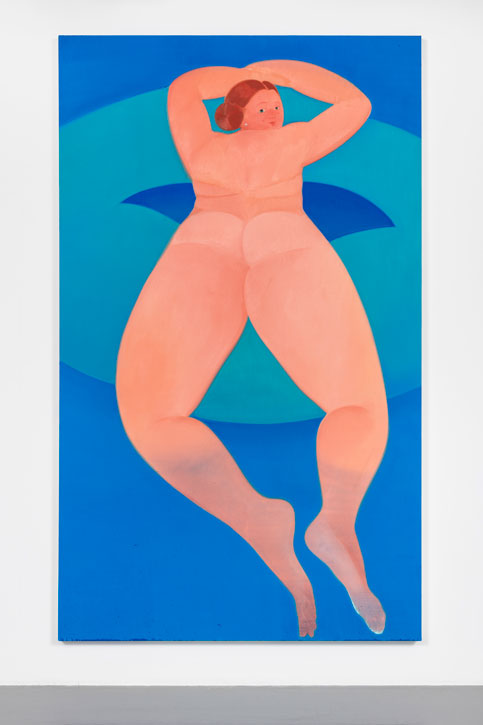

Aquamarina, Caryatids, Opalescent Skies

2021, oil on canvas by Sofia Mitsola (b.1992)

Lydia Figes, Art UK: Your work The Evil Eye in the Jerwood collection plays with the gaze while alluding to Greek classical antiquity – can you tell us more about the conceptual thought process behind this work?

Sofia Mitsola: This is the first painting where I started to think about amulets and charms of protection in my work. I have been reading about the evil eye in Eastern cultures, Egypt, Turkey, and Greece and connected the idea of the gaze and protection and how I could use the gaze of my characters as a protective power.

I realised the evil eye is very much connected to the Greek mythological symbol of Medusa, a monstrous gorgon who turned to stone anyone who dared to look her in the eyes. I wanted my figures to be like Medusa and the evil eye. If you stand with them, relating to them, you are protected. And if you stand against them, they become your worst nightmare.

In The Evil Eye, the female nudes are standing tall, forming a bond. Their seductive presence invites the viewer to come closer, to flirt with them. The viewer might at first think, that they are there to take pleasure from these enchanting nudes. But once closer to the works, these figures submerge and intimidate the viewer: they revert the gaze and challenge the visual consumption of the audience through their colossal size and penetrating stare.

For me, it is very important to compose confrontations between the viewers and the paintings. In my mind, the confrontation takes place the moment the viewer stands before the painting and gazes meet. And in a way, the paintings will always win, because the viewer will eventually withdraw but my characters will never stop looking.

After working on The Evil Eye, I began to think more about amulets and how I could invent my own charms of protection. For my latest show, I have made paintings of jewellery and precious stones set in geometrical designs. These are trophies, collectables of my protagonists which are also meant to attract the viewer and play with the theme of enchantment. These are woven into the narrative of my characters and also provided many of the titles and descriptions for my paintings.

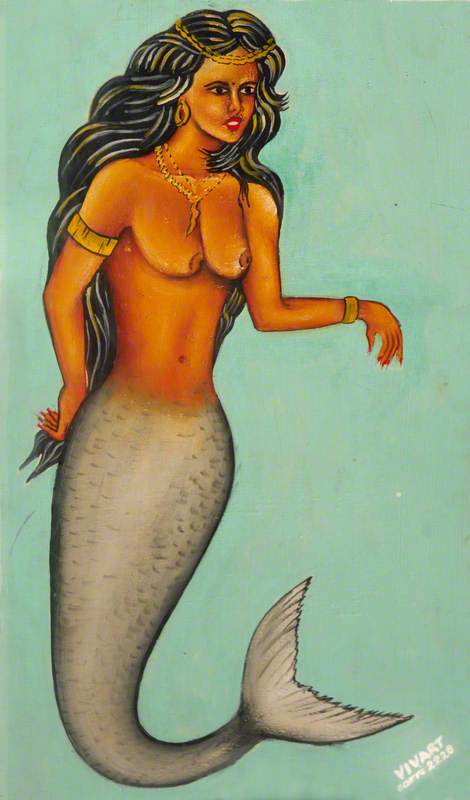

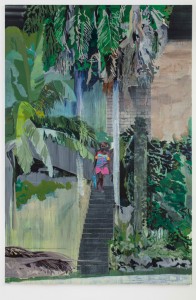

Siren

2019, oil & acrylic on canvas by Sofia Mitsola (b.1992)

Lydia: The female form is a central theme in your work. But what compels you to focus on the female body rather than the male body?

Sofia: In this series, there are male characters too, but yes the protagonists are always women. This relates to the myth I have developed over the past year, which is narrated from a first-person perspective. I need my story to be reliable, and for viewers to relate to the characters (or perhaps not identify with them at all). Since I know my body, and I know what it means to live inside of it, I feel that to work with female figures is the closest thing to me.

In this series, male characters take the form of crocodiles, as seen in the predatory character Crocovelus Niloticus. The title of the exhibition, 'crocodile tears', refers to my research into reptilian species and predatory behaviours. But it also plays on the expression that dates back to the sixteenth century. It emerged from a belief that crocodiles shed tears while luring or devouring their prey. It means 'fake remorse', or insincere, pseudo tears.

I wanted to suggest that my crocodilian figures are predators, but at the same time, my female figures – who fight and kill the character Crocovelus Niloticus – are the even bigger predators. They are the ones crying the crocodile tears; while they lure in, and kill their prey.

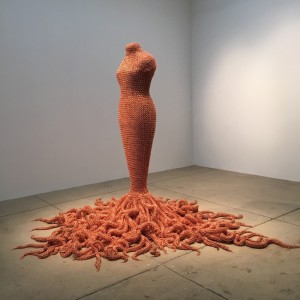

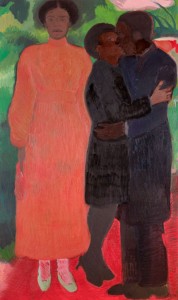

Balona

2020, oil on canvas by Sofia Mitsola (b.1992)

Lydia: Are your figures totally imaginary? And if so, how do you visualise them?

Sofia: Yes, my figures are imaginary and constructed over a long period of time. In my mind, they are all part of the same family and I see them as descendants of previous figures I have painted; they are related by blood with the sphinxes and sirens I have made in the past.

And even if they have developed and lost their monstrous half-human half-animal bodies, they still have the powers of their ancestors. The more I work with these figures, the better I can understand their personalities. This year I worked with painting, writing, and drawing, to compose them as complete characters, like the ones in novels or films.

My protagonists are sisters and huntresses, named Aqua and Marina. They sometimes appear separately as individuals, but also double up to become one 'Aquamarina'. I chose the name for its doubleness, and its multiple meanings. It can refer to the precious stone Aquamarine, the water, and the sea. In my myth, the sisters are opposites who become complete together.

When I was composing the narrative I understood that the tale may not be 'reliable', but for me what was important was for it to be convincing. Like when you read about myths or the Bible and you simply know that it would be impossible for such things to happen but still you choose to believe them so you get on with the story and enjoy the tale. Through the way the myth is written or painted it becomes convincing and eventually exists. Maybe it does in its own terms, but it exists all the same.

I have been looking at historical paintings, especially ones about the myth of Diana – the goddess of hunting, the moon and wild animals. Titian's depiction of Diana and Actaeon in The National Gallery captures the moment when Actaeon stumbles upon Diana naked as she bathes with her female entourage. She turns him into a stag through one furious glance. The hunter becomes hunted and later is killed by his own hounds. The story of Aqua and Marina is very 'close' to the tale of Diana, who uses her powerful gaze as a weapon, to protect herself. Both myths are about looking, and being looked at.

Lydia: Where did the aquatic theme of this show originate?

Sofia: I have always been infatuated with water, which is definitely connected to the fact that I'm Greek. Being close to the sea and snorkelling are my favourite things to do in the summer. When you go underwater, your sense of gravity and perception changes. For me going beneath the surface of the water is almost like accessing another world. And so the aquatic world has in my work become a metaphor for a world with its own terms.

In my paintings, I work a lot with transparencies and translucencies made with turpentine washes next to opaque areas of colour. Water in my practice is about cleansing and catharsis, but is also a transformative substance. At the beginning of the myth, my protagonists appear angelic, celestial beings, but later morph into aquatic, predatory sea monsters.

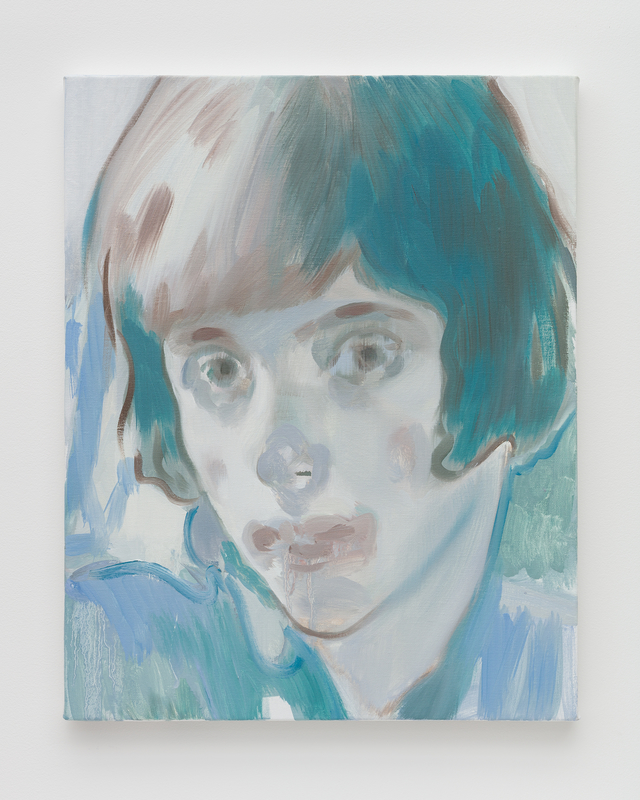

Soft

2020, oil on canvas by Sofia Mitsola (b.1992)

Lydia: Do you have any studio rituals? An evil eye perhaps?

Sofia: I don't have an evil eye actually, but I have things that I have collected, seashells, velvet and silk fabrics, drawings of jewellery, or other found objects. I have many pictures of paintings that I like (a Paula Modershohn-Becker, a Pre-Raphaelite painting, Picasso's Reve, Petrus Christus' Portrait of a Young Girl) as well as mini sculpturettes I make occasionally.

All these things, I keep displayed in my studio and recently started to think of as having special powers. I realised that motifs from these objects are 'jumping' into my paintings – I don't necessarily collect and keep them for a direct purpose, but they eventually manage to enter the work.

In terms of rituals, I listen to Baroque music, and Queen, and Dalida but I also love listening to films in the background. A lot of Kill Bill, The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover, (the costumes were designed by Jean Paul Gaultier).

Lydia: Which artist from history would you like to have dinner with?

Sofia: I don't think I would want to have dinner with anyone from history, especially the ones I really admire. I like to make stories in my head about how these people might have been and reality would ruin that for me.

Aquamarina

2021, oil on linen by Sofia Mitsola (b.1992)

Lydia: What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Sofia: First of all, work hard... and then work even harder.

But it's not only about working hard. It's also about believing in what you are doing. Once you make a decision about what you want to do, commit to that idea and don't doubt it. Work hard to solve it, and find the best way for it to exist.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Sofia Mitsola's latest solo show 'Aquamarina: Crocodilian tears' is on at Pilar Corrias until 2nd October 2021