In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

The Bristol-born photographer Stephen Gill isn't concerned with capturing what a place looks like, but rather how it feels.

For Gill, photography isn't an exercise of forcing a particular narrative or vision onto a subject. Following a non-invasive photographic philosophy, Gill's work carefully and sensitively probes into nature; investigating an elusive and often concealed natural world that runs in parallel to the relentless chaos of human life.

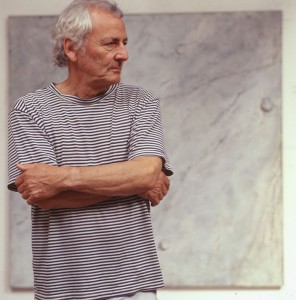

From 'The Pillar'

2015–2019, photograph by Stephen Gill (b.1971)

Now based in rural Sweden, the photographer continues to push the bounds of his imagination and photography to celebrate the overlooked beauty of nature. He will return to the UK for his major exhibition, 'Coming up for Air: Stephen – A Retrospective', open to the public at Arnolfini, Bristol from 16th October 2021 until 16th January 2022.

Spanning almost four decades of work, the show assembles Gill's versatile photographic experiments, from his early forays in black and white photography, to his more recent conceptual experimentations with the medium. I spoke to the photographer to find out more.

Lydia Figes, Art UK: The Arnolfini show surveys 30 years of your practice. What were the challenges or delights of curating a show that spans so many years?

Stephen Gill: For the past 35 years I've barely stopped producing new work, so it was quite an experience to take a pause and reflect back. My whole career has been about looking forward and constantly making new work, so it was interesting to revisit a lot of my early work, especially the work that has never been printed or published. The fact that it was during COVID-19 times made it hard.

When you stop and look back at what you have created you can see how things that once seemed completely separate are linked and entwined, even though aesthetically or in terms of subject matter they might appear to be quite different.

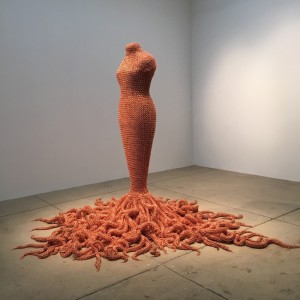

From 'Hackney Flowers'

2004–2007, photograph by Stephen Gill (b.1971)

Lydia: Nature has always been a central theme in your practice. How has this relationship to nature evolved?

Stephen: I think it goes back to my early interests in nature as a child. I had a craving for nature because I lived in cities all my life (Bristol until 1993, followed by London until 2013). I subconsciously always felt drawn to nature. A lot of my London work focuses on nature despite being about the city – for example, my series Hackney Wick explored the allotments, meadows and canals, and my series Hackney Flowers pressed flowers and seeds from the area onto the photographs.

Now I live in a quiet setting surrounded by nature, which aligns with how I like to work. When I moved to Sweden I realised that nature would play a big part, simply because it is so rural here. My imagination has to work harder, as when you look out of the window it's just miles of fields and sky – it's a blank canvas to the naked human eye. Whereas in London, I had a heightened sensitivity to my immediate surroundings. I always needed to decipher the busy environment quickly and filter out what was unnecessary.

In my Night Procession series, I wanted to capture a parallel world that comes alive outside while we are sleeping. In daylight hours I placed motion-sensitive cameras inside the nests of birds and animals, and then went home. Most of those pictures were created while I was asleep – I let chance and the movements of nature and animals determine the final shot.

From 'Pigeons'

2012, photograph by Stephen Gill (b.1971)

I don't like the idea of projecting my idea of nature onto the work. I prefer to step back, which is something I have been trying to do for years. It's about allowing the subject to determine the work instead of orchestrating it as the author. My role is to simply create a stage or platform where events can naturally unfold.

Although I now live in the remote countryside, sometimes I still miss the chaos of a city. There will always be a kind of loyalty to London – that city became too visually overwhelming, but it also gave me so much creatively. In the end, like many people, I started associating the city with work. People can become addicted to the chaos of London.

Lydia: Your photographs often have a painterly quality and you tend to use lots of different techniques. Could you tell us how your conceptual experimentations began?

Stephen: I think they began in around 2001. I had been making work for almost 15 years, but I felt that straight, descriptive photography had limits. I wanted to figure out ways to bypass what I called the 'glass wall' of photography. We were in a time of digital enhancement, so conversations about film and photography felt suffocated by new ideas and novel techniques. For me, it felt like some kind of soul or feeling was lost at the expense of new information.

In reaction to this, my project Hackney Wick, which used a slightly dodgy plastic camera, taught me that even though information was denied, my murky images still managed to capture a particular feeling that was unique to that place. That pushed me to find new ways to discover a place or capture the 'essence' of a place, without resorting to using updated forms of technology.

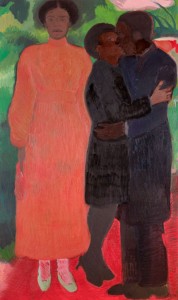

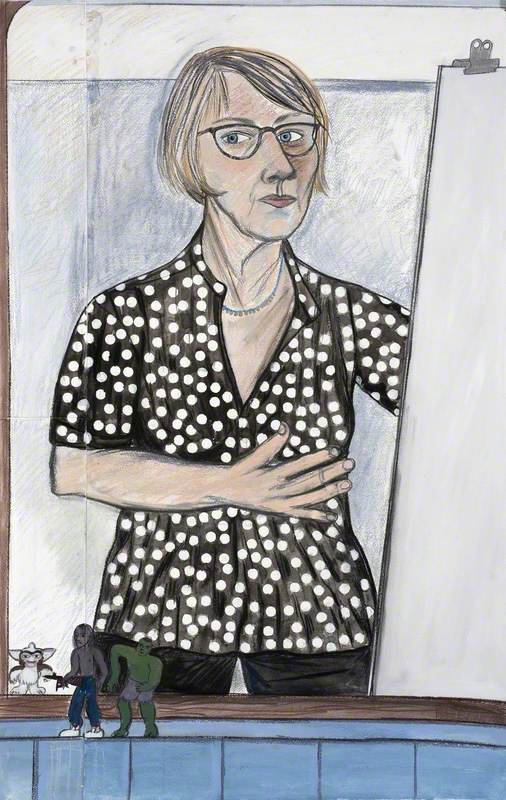

Coexistence

2011, photograph by Stephen Gill (b.1971)

Lydia: At what point in your career did you reject the idea of having a 'signature style'?

Stephen: When I got older I wanted to push the subject to the forefront – this would determine the style rather than the other way around. There is a danger with photography, where sometimes the medium can suffocate the subject. I wanted to de-emphasise my role as the author.

In my early work I wanted to exclude visual noise and simply focus on black and white photography. It's a great place to start because you learn about light, shape and form. After a while I almost felt frightened to move into colour, especially as photographing in London can introduce so many intense colours that disrupt harmony. But in the late 1990s, I changed my mind. Working in colour was like learning a new language, but I never looked back.

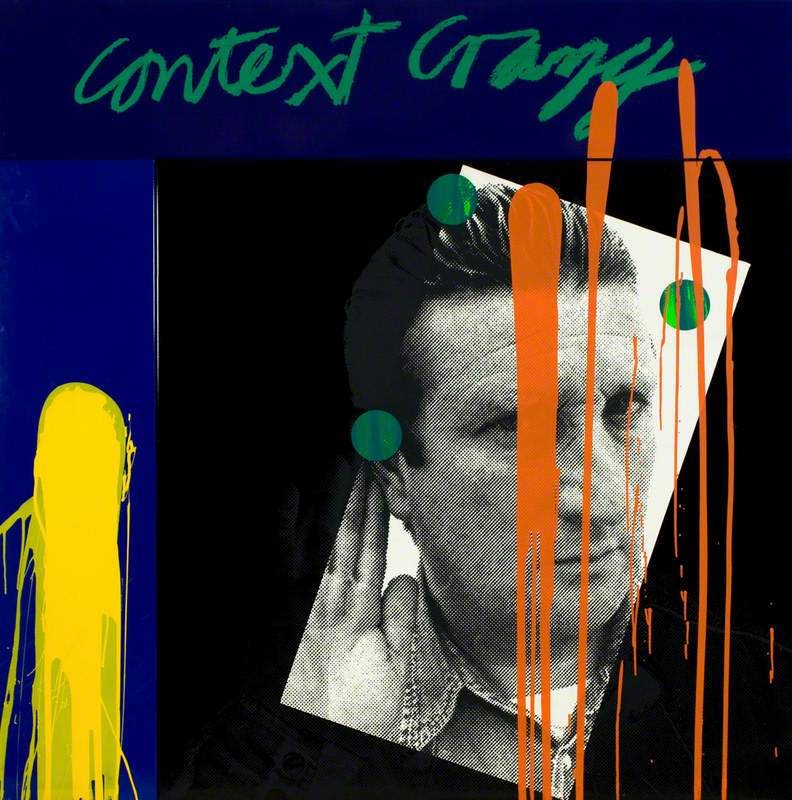

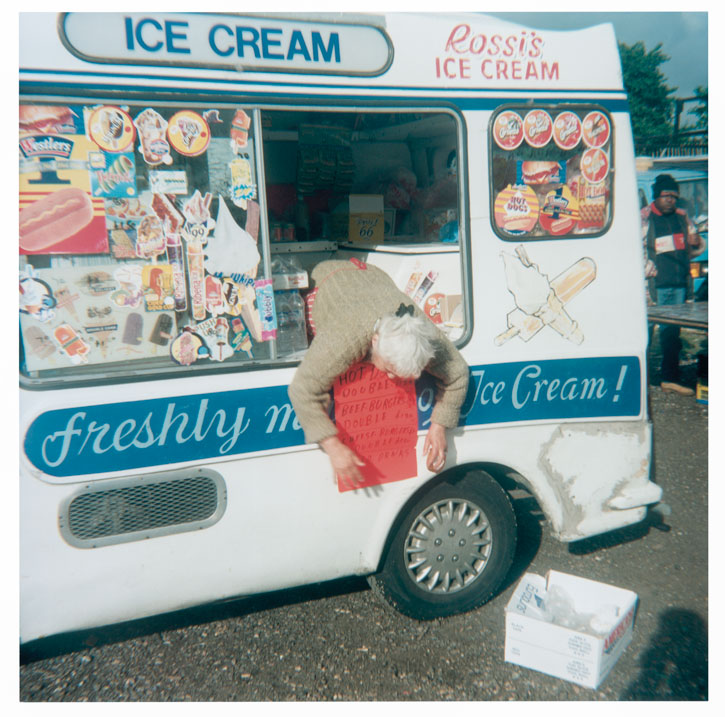

Now my work embraces visual noise and even fluorescent colours. Works from Hackney Wick utilise milky colours. The photograph of the woman in the ice cream van was taken on a Sunday in Hackney Wick market ten minutes from my house. I felt overwhelmed because I hadn't registered this market before. It's a part of London that is full of contradictions –bus depots and industrial sites right next to meadows and canals. There was something special about the market even though it felt quite desperate.

From 'Hackney Wick'

2001–2005, photograph by Stephen Gill (b.1971)

I bought a camera for 50p that day and began taking photographs. It was one of the first times ever that I was completely carried by the place, so in a way that photograph made itself. She is in the middle of sellotaping a sign onto the bus. But the act of her leaning adds a new component to the picture – it somehow jars.

Lydia: Can you explain why you regularly return to the area of East London, and in particular of Hackney?

Stephen: Because I lived there, but also because there was so much inspiration. I used to cycle at 5am along the canals in Hackney Wick and would find such beautiful sites – foxes and birds moving quietly around the city. Hackney always struck me as quite a magical place, and it carried my work. The ability to see it from the perspective of my bike added an element of escapism.

From 'Night Procession'

2014–2017, photograph by Stephen Gill (b.1971)

Lydia: Some of your photographs capture a sense of nostalgia or even a haunting quality. Are you aware of creating this effect in your work?

Stephen: I've been told that works from the Night Processions series are quite heavy and sinister, but perhaps that's because at the time there was so much going on in the world, and arguably these things become embedded onto the pictures when they are interpreted.

Really these are studies of nature – the strange green quality comes from plant pigments I used to make the prints. These studies show how oblivious nature is to the world inhabited by humans – the intention was never to amplify or force a subject or concept. If my work is read with a haunting or nostalgic quality, it is not because I have intentionally created them to be that way.

From 'Talking to Ants'

2009–2013, photograph by Stephen Gill (b.1971)

Lydia: What advice would you give to aspiring photographers today?

Stephen: Photography can be quite solitary, sometimes it feels like you are swimming against the tide, and people will inevitably question what you are doing. But you have to believe in yourself and trust your instincts.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Coming up for Air: Stephen – A Retrospective' is at Arnolfini, Bristol from 16th October 2021 until 16th January 2022