In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Race, gender and sexuality are at the heart of British-Nigerian artist Tayo Adekunle's powerful photographic images and digital collages. Originally from Wakefield in West Yorkshire, Tayo studied photography at Edinburgh College of Art, graduating in 2020, and now lives and works in London.

Since graduating, she has undertaken a commission with the University of Edinburgh, making work in response to the organisation's phrenology collection held at its Anatomical Museum. She was selected to make work for the New Contemporaries exhibition at the Royal Scottish Academy, and last year received the Society of Scottish Artists' Award for her work Yemoja.

Working mainly with complex images of self-portraiture and digital photographs, Tayo's work explores racial and colonial history, frequently exploring archives and referencing historical material and artworks including paintings, sculpture and photography.

Tayo Adekunle in the studio

Rhona Taylor, Art UK: You graduated in 2020, which was a difficult time for anyone to be leaving university. What have you been working on since then?

Tayo Adekunle: I graduated into a pandemic – I stayed up in Edinburgh for a year and had a space in a photography studio, so could make some new work, and then moved to London. I was really lucky to have a studio to go to when everyone was working from home. I also had the commission (Fitting the Character) that I worked on with Edinburgh University.

The difference between being a student at university, and then being an artist after you've graduated is massive. You have to get used to not having a huge network of artists, or having to make constant work for crits. So it's been interesting and fun adjusting to that.

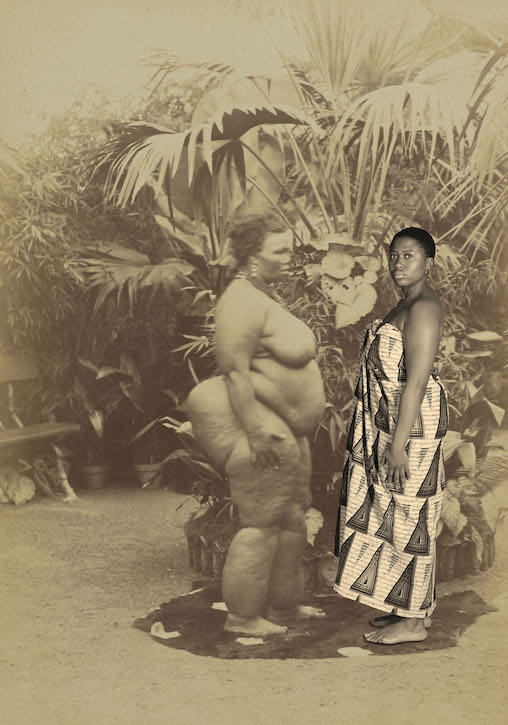

Artefact #03

2020, digital collage by Tayo Adekunle

Rhona: You're from Yorkshire, have lived in Scotland and London, and have Nigerian heritage. How does your relationship with those different places feed into your work?

Tayo: It feeds into all my work in some way. It's who I am as a person. In some of the Artefact images, I'm wearing Western contemporary clothing – those images show the relationship that my own body has with those women's bodies. I used contemporary clothing in some of the images to show how our links surpass this cultural barrier.

Reclining Venus

2019, digital photograph by Tayo Adekunle

Or for example in my series Vénus Noire, I draw on a lot of different things from different cultures. So there are references to classical Western painting, for example reclining nudes, or Greek sculptures, but then there are also references to Nicki Minaj and Kim Kardashian.

Rhona: Can you tell us about your recent work Yemoja?

Tayo: I made that piece when we were in heavy lockdown in Scotland. I was negotiating ideas and feelings of inherited trauma and inherited loss pertaining to black people, and I had been watching a BBC documentary, Enslaved, with Samuel L. Jackson. They were looking at different elements of the slave trade that not many people talk about.

Yemoja

2021, digital collage by Tayo Adekunle

From that series, I found certain elements that really stuck out to me. So at the bottom of the piece, there are some elephant tusks that I made. And then in a circle around my head are things called manilla, which were used as currency in the slave trade. I also photographed some sugar cane, and I put all of those symbols of the slave trade in there.

But then I've also got this figure of me dressed as Yemoja. She's a motherly deity, a water spirit and has associations with the moon. So she's also a very comforting figure.

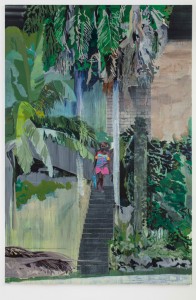

Reclamation of the Exposition #3

2020, digital collage by Tayo Adekunle

Rhona: Do you think of your work as self-portraiture, or is it not that important that it's you in the images?

Tayo: I started using myself just to test out ideas. The plan was that I was going to get models in and then reshoot, but I really struggled to find models. Also, throughout my work, I've been commenting a lot on objectification and othering, and I didn't want to do that to someone else. I don't want people to feel pressured to go along with it.

The work relates to me as well – all my work is personal. So for example the Vénus Noire series really helped me to unlearn things about my own body, and accept the way that I look at it. So I guess unintentionally, it's become quite important. But I tend to just use myself because it's easier, and I can experiment a bit more.

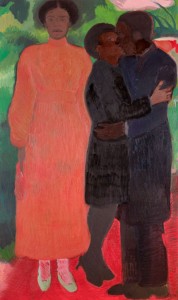

Crouching Venus

2019, digital photograph by Tayo Adekunle

Rhona: How do you go about researching the historical images that you use in your work?

Tayo: For my dissertation, I was researching how the notions surrounding black women's sexuality – the idea of black women either being hyper-sexual, or devoid of sexuality – were rooted in racist eighteenth- and nineteenth-century scientific writing.

From there, I was looking at how those ideas have spread throughout visual culture into the twenty-first century. I came across colonial and ethnographic photography, and I knew I wanted to talk about colonialism, because it's one of the biggest things to talk about in the topics that I was researching.

But the images were actually kind of hard to come by. I found a lot of them in a book that I was using for my dissertation and then also just tried to scour the web. But a lot of museums haven't digitalised their archives or their colonial/slavery archive, so it's hard to get those images. It felt weird actually trying to hunt down these images, which are pretty graphic and horrific. But it also felt strange that I was having to look so hard for them.

Lady (1840)

2019, vinyl mounted on a lightbox by Tayo Adekunle

Rhona: Could you tell me about the residency that you did at Hospitalfield in Arbroath?

Tayo: That was a micro-residency as part of my university course. We were introduced to Hospitalfield, and told to make site-specific work that responded to the site. The work I made was my first go at self-portraiture, and was the springboard for the kind of work I make now.

I was quite nervous – I was really into portraiture, and with site-specific work, I was like, 'Ah, this sounds like it needs to be architectural.' But there was a lot of portraits around the site, so I responded mainly to those.

It was very noticeable that there only just only white, rich people in these paintings. In the few paintings that had black people in them, they were always slaves, which makes sense historically, but was something that I wanted to address.

'Lady (1840)' in the Portrait Room in Hospitalfield

2019, vinyl mounted on a lightbox by Tayo Adekunle

The black pigment that they used to use in these paintings was a really reflective surface, so depending on what angle you are viewing the work from, sometimes you were just getting light reflected back at you. So it obscured most of the figure's face.

I made a photograph that was mounted on a dimmable lightbox. That began this thing of me making fake histories. I made a character of this upper-class black woman who was given a place in the portrait room.

Rhona: Are there any artists who you particularly look up to?

Tayo: Harmonia Rosales is a Cuban artist who sort of reworks classical paintings and puts black figures in them, and I also like Lorna Simpson. There are a lot of black artists who are talking about very similar things – those ideas of representation and meanings of the definition of beauty.

Rhona Taylor, Commissioning Editor – Scotland, at Art UK