The contemporary art scene, with its increasingly global scale and intellectual stakes, might have us think that painters and sculptors found it easier to obtain commissions in the past, when competition was mostly local and artworks, as objects of craftsmanship, were more integral to people's everyday lives. Think again.

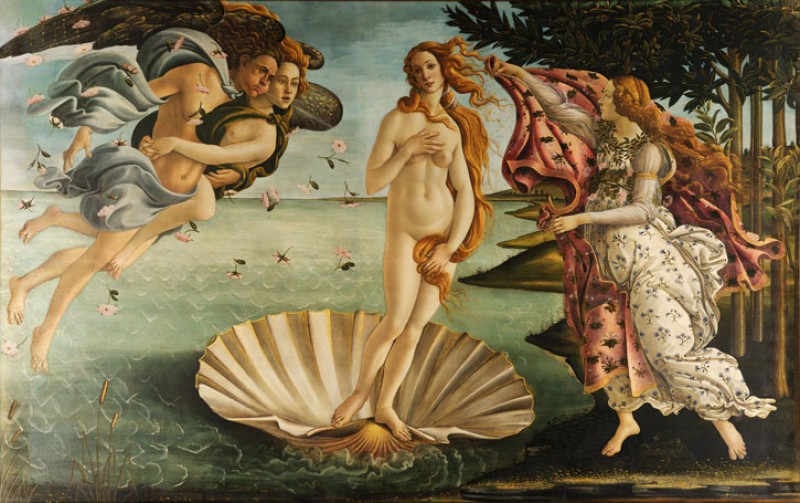

The Virgin Adoring the Christ Child (The Ruskin Madonna)

c.1470

Andrea del Verrocchio (1435–1488) (attributed to)

In fifteenth-century Florence, for example, artists vied for commissions in a competitive market, expertly striking a balance between tradition and innovation, and increasingly exploring architectural design as a form of communication.

The Abduction of Helen

about 1450-5

Zanobi Strozzi (1412–1468) (attributed to)

The Church and the government offered the largest and most prestigious commissions, often organising competitions to assign work. The most famous cases are the contest to realise the relief panels for the north doors of the Florence Baptistery (1401) and that to build the dome of the Duomo, or cathedral (1418).

Two versions of 'The Sacrifice of Isaac'

1401, gilded bronze by Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455; left) and Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446; right). Created as entries for the competition to decorate the Baptistery doors of San Giovanni in Florence. Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence

The stakes were high and competition fierce: these were long-term commissions ensuring secure income for years, as well as the potential of further commissions thanks to an increase in prestige and notoriety. Sometimes these competitions dramatically changed the course of an artist's career.

The dome of Florence Cathedral, seen from the Bell Tower

dedicated 1436, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446)

Filippo Brunelleschi's failure to secure a single-handed commission for the Baptistery's north doors may have spurred him to abandon metalwork and take up architecture, winning the competition for the dome of the Duomo and becoming one of the most celebrated practitioners of the early Renaissance.

Detail of the façade of the Ospedale degli Innocenti (Foundlings' Hospital), Florence

1419–1445, by Filippo Brunelleschi (1377–1446)

Brunelleschi's versatility highlights the close connection between architecture and the arts at this time, as well as pointing towards the emergence of the architect as a new professional figure. But rarely was it all about a single individual – while historiography has tended to celebrate figures such as Brunelleschi and Lorenzo Ghiberti for their skill and inventiveness, it is worth remembering that they were surrounded (and often supervised) by a wide range of experts ensuring the quality of the work.

The San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece

1370–1371, egg tempera on wood by Jacopo di Cione (c.1320–1400) and workshop

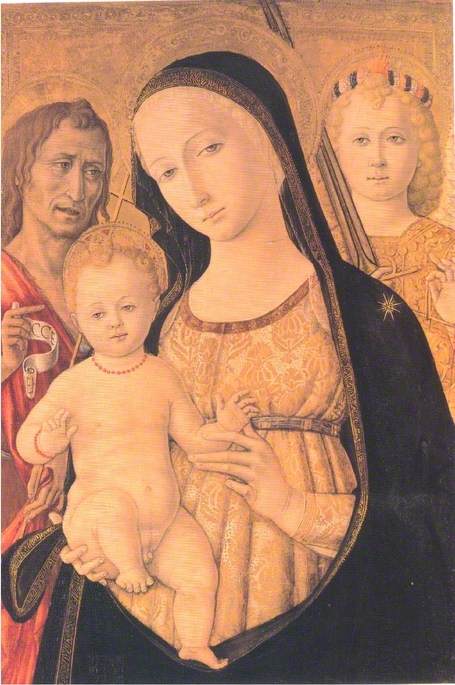

Religious confraternities and wealthy individuals or families – such as the Medici – were important patrons too. Many commissions revolved around the dedication of chapels, which artists were asked to decorate with fresco cycles, often portraying the life of a saint, or altarpieces. The result of intense collaborations between painters and carpenters, these large paintings traditionally feature a central, larger panel representing the Virgin and Child surrounded by smaller panels representing saints, though other iconographies could feature, such as the Coronation of the Virgin or the Crucifixion.

Figures stood against a gold background and were clearly separated by more or less elaborate wooden frames, which sometimes reproduced architectural forms such as columns, gables or pinnacles. These types of panel paintings continued to be produced during the fifteenth century, for example, Masaccio's altarpiece for the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Pisa (1426). Increasingly, however, artists adopted a single-panel arrangement, in which figures are not separated from each other and occupy the same natural or architectural setting rather than standing against a gold background.

The Virgin and Child Enthroned among Angels and Saints

1461-2

Benozzo Gozzoli (c.1421–1497)

Benozzo Gozzoli's altarpiece for the Confraternity of the Purification of the Virgin and of Saint Zenobius (1461–1462) is an example of this: angels and saints are in adoration of the Virgin and Child in an outdoor setting marked by vegetation at the bottom of the panel and tree tops in the distance.

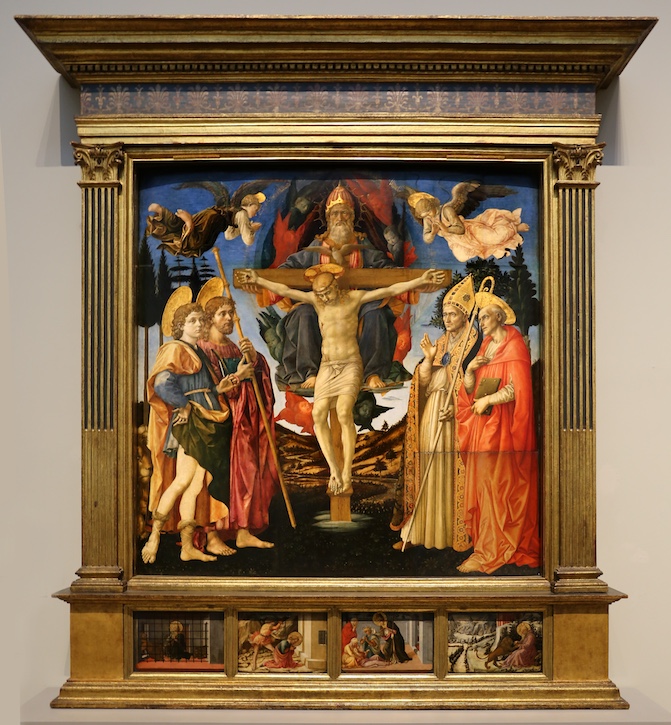

The Pistoia Santa Trinità Altarpiece

1455–1460, egg tempera, tempera grassa & oil on wood by Francesco di Stefano Pesellino (c.1422–1457) and Filippo Lippi (c.1406–1469) and studio

A further example is Francesco di Stefano Pesellino's altarpiece for the church of Santa Trinità in Pistoia (commissioned 1455; taken apart in the late eighteenth century), later completed by Filippo Lippi. While this altarpiece stands out for its depiction of the Holy Trinity, a relatively uncommon iconography, it also represents all figures in the same uninterrupted, outdoor setting. These changes mark a growing interest in the representation of natural and architectural detail, and in providing a credible, shared space for all the figures. This altarpiece will be included in The National Gallery's upcoming exhibition 'Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed'.

Saint Gabriel: Left Pinnacle

about 1420-4?

Giovanni dal Ponte (1385–c.1437)

Interestingly, the frames continued to include prominent architectural elements, although they increasingly adopted classical capitals and trabeation over pinnacles and gables. While it is important to remember that a great deal of altarpiece frames are not original – as in the frame surrounding the Giovanni dal Ponte image above, which was remade in the nineteenth century – the continued presence of architectural forms in those that are (and in those that were remade to copy exactly the original) testifies to an active engagement with architecture on the part of all the craftsmen involved in the making of these objects, highlighting lively exchanges across art and architectural practice.

Leonardo da Vinci's The Virgin of the Rocks (c.1491–1508) was formerly displayed in a nineteenth-century frame, but the work's current frame was remade in 2010 to include original fragments from a sixteenth-century north Italian frame.

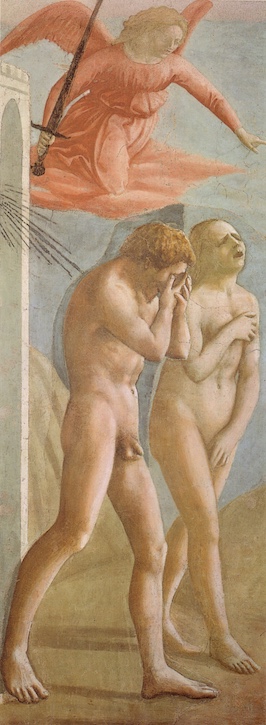

Architectural and natural settings also came to define fresco cycles. The Brancacci Chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine (1424–1428) by Masolino and Masaccio, later completed by Lippi in 1480, and the Sassetti Chapel in Santa Trinita (1482–1485) by Domenico Ghirlandaio are two of the most innovative fresco cycles of the fifteenth century.

The Expulsion from Paradise of Adam and Eve

1424–1428, fresco by Masaccio (1401–1428), Brancacci Chapel, Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence

These works more clearly reveal the representation of depth, a broader emotional range and, in Ghirlandaio's work, a recognisable Florentine cityscape through his depiction of Piazza della Signoria.

Confirmation of the Franciscan Rule

1482–1485, fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494), Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinita, Florence

They demonstrate the ingenuity of the artists involved as much as the prestige of the influential families who paid for the work.

But commissions were not solely religious: plenty of objects were intensely personal, such as portraits, or were commissioned to mark special occasions, for example, cassoni (wedding chests) or deschi da parto (birth trays), which usually commemorated weddings or the birth of a child. They often represented allegories or subject matters based on ancient history or tradition.

The Triumph of Scipio Africanus

Apollonio di Giovanni di Tommaso (c.1415/1417–1465)

Apollonio di Giovanni di Tommaso's The Triumph of Scipio Africanus, for instance, depicts Scipio's triumphant return to Rome, including key landmarks such as the Colosseum and the column of Trajan.

The Story of David and Goliath

about 1445-55

Francesco di Stefano Pesellino (c.1422–1457)

Yet, cassoni also portrayed biblical stories: Pesellino's The Story of David and Goliath (c.1445–1455) represents a chaotic battle scene outside the walls of a city in a flowery landscape evocative of the Tuscan hills. Often, there is little evidence linking these furniture panels to specific patrons, and Pesellino's cassone is no exception, though emblems on some of the figures' clothing suggest it could have been made to celebrate a wedding in the Medici family.

The few examples mentioned here testify to a very lively art market in which competition and collaboration drove the standards of craftsmanship to outstanding levels, and where high demand led the most successful artists to meticulously organise production in their busy workshops, such as Sandro Botticelli's.

The Madonna and Child with the Infant Saint John

1490s

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510) (studio of)

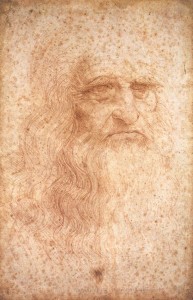

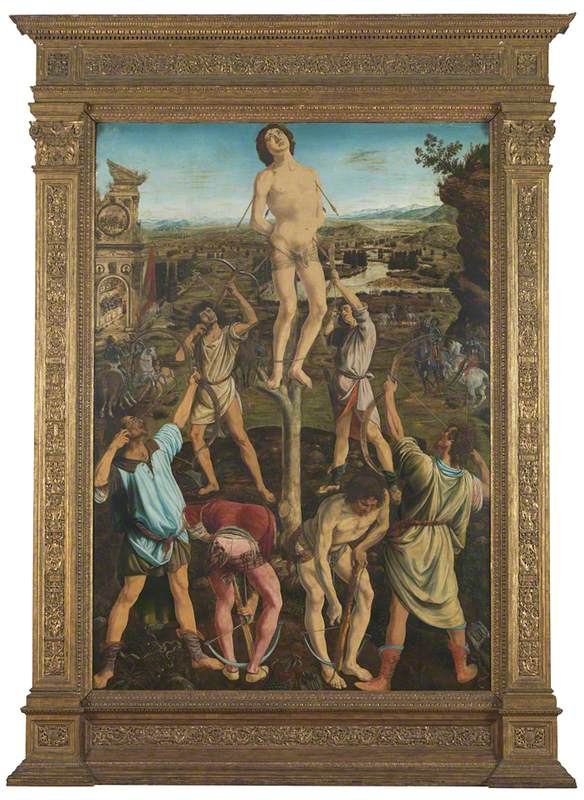

Against this bustling background, artists such as Masaccio and Pesellino, who died at 27 and 35 years of age respectively, are all the more remarkable for their influential contributions. The vibrancy of the art scene in fifteenth-century Florence fostered innovation to unprecedented levels, not only by creating new formats such as altarpieces with a single main panel, but also by methodically tackling three-dimensionality, exploring emotions, engaging with human anatomy and reinterpreting the classical tradition.

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian

completed 1475

Antonio del Pollaiuolo (c.1432–1498) and Piero del Pollaiuolo (c.1441–before 1496)

These developments are at the heart of Western art as we know it, and have been embraced, elaborated upon or even rejected by artists throughout history, from Mantegna to Magritte, from the Pre-Raphaelites to Picasso. They represent a historiographical canon that is as inspiring as it is problematic, shaping to this day our relationship with art and heritage.

Livia Lupi is a historian of art and architecture of the early modern period

'Pesellino: A Renaissance Master Revealed' is at The National Gallery, London, from 7th December 2023 to 10th March 2024

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Cristelle Baskins, Adam W. B. Randolph et al., The Triumph of Marriage: Painted Cassone of the Renaissance, Periscope Publishing, 2008

Ana Debenedetti, Botticelli: Artist and Designer, Reaktion, 2021

Amanda Lillie et al., Building the Picture: Architecture in Italian Renaissance Painting, National Gallery, 2014

Livia Lupi, 'Brick and Mortar, Paint and Metal: Architecture and Craft in Renaissance Florence and Beyond' in Architectural Histories, vol. 1 (2023)

Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, Art, Marriage, and Family in the Florentine Renaissance, Yale University Press, 2009

Christina Neilson, 'Demonstrating Ingenuity: The Display and Concealment of Knowledge in Renaissance Artists' Workshops' in I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance, vol. 19, no. 1 (2016)

Scott Nethersole, Devotion by Design: Italian Altarpieces before 1500, National Gallery, 2011

Michelle O'Malley, Painting Under Pressure: Fame, Reputation and Demand in Renaissance Florence, Yale University Press, 2013