I was a student at Yale University in the late 1980s when I fell in love with Renaissance literature. In a course entitled 'Major English Poets', I was introduced to Edmund Spenser, John Donne and John Milton.

I studied Shakespeare in large lecture halls and in small seminars; I read lots of sonnets. But when I graduated with a BA in English, I had never read a word written by a woman before the nineteenth century. Nor did I imagine there were things to be read. I took Virginia Woolf at her word when she told me in A Room of One's Own that no woman could have ever made it as a writer in Shakespeare's England.

Six years as an English graduate student only confirmed this impression. There, I plunged into classes on Renaissance theatre, and learned about the Reformation, the Counter-Reformation and the witchcraft craze.

Macbeth, Banquo and the Witches

(from William Shakespeare's 'Macbeth', Act I, Scene iii) 1793–1794

Henry Fuseli (1741–1825)

I read sermons, political treatises, prayer books and travel narratives. But when I received my PhD in 1996, I still hadn't encountered a single woman writer from the Renaissance.

Part of this was my own fault. I never asked any of my professors whether any women might be included in their exclusively male syllabi. But until the 1990s, most Renaissance women writers were unpublished, out of print or appeared in books that obscured their authorship.

Probably Elizabeth Cary, née Tanfield

c.1614–1618

William Larkin (c.1585–1619)

Elizabeth Cary's 1613 Tragedy of Mariam hadn't been reissued outside of a scholarly facsimile in 1913; Aemilia Lanyer's Salve Deus first surfaced after more than 300 years under the misleading title The Poems of Shakespeare's Dark Lady; Mary Sidney's Psalms were published in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries under her brother's name or with her name subordinated to his.

Anne Clifford's early diaries came out in Sackville-West's 1923 edition, but her other autobiographical writings were unavailable.

Anne, Countess of Pembroke (Lady Anne Clifford)

c.1650

Peter Lely (1618–1680) (after)

And then everything changed. Thanks to the amazing work of feminist scholars and editors in the last few decades, Renaissance women writers have been resurrected from the dead. A full edition of The Diaries of Lady Anne Clifford was first printed in 1990 and the Great Books of Record in 2015; a critical edition of Aemilia's Salve Deus in 1993; Elizabeth Cary's Tragedy of Mariam and her daughters' memoir of her life in 1994; and The Collected Works of Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke in 1998. Scholarly essays and books on these women and their contemporaries began to appear. A new field was born. But unless you found yourself at a university where someone was doing this work, it was entirely possible to hear nothing about it.

Mary Sidney (1561–1621), Countess of Pembroke

Federico Zuccaro (c.1540/1541–1609) (attributed to)

Today, the situation has, in many ways, changed again. There are anthologies of women's writing that include materials far beyond poems and plays, giving readers access to letters, prayers, pamphlets, diaries, domestic treatises and all sorts of occasional writing by women whose names we'd never heard before. In the classroom, these women now frequently show up in syllabi otherwise dedicated to works by men. The situation has certainly improved from my time at Yale 35 years ago.

And yet. When a young friend of mine studying tragedy at Cambridge University in 2021 asked if she could write about Elizabeth Cary's play, her professor told her he'd never heard of it. To his credit, he gave her permission – and maybe next time he'll even include The Tragedy of Mariam in his course – but the anecdote is by no means unusual. Many scholars working in the field still never teach anything written by Renaissance women. In the larger public, few have heard of many of the women in this story, and therefore – and possibly more importantly – it's also rare for them to know anything about what it was like to be a woman in Shakespeare's England.

It's important to affirm that these women absolutely stand up to their male counterparts. One of the questions I'm frequently asked, when I talk about these writers is, are they any good? Putting aside the offensiveness of the question, with its underlying assumption that the canon has done its work and kept out the lesser talents, it's important to affirm that they are indeed 'good' by literary standards: Aemilia Lanyer and Mary Sidney are brilliant poets, Elizabeth Cary is a first-rate playwright and Anne Clifford is one of the great diarists of the era.

Shakespeare's Sisters: Four Women Who Wrote the Renaissance

Ramie Targoff (2024)

And the list by no means stops here. I've chosen these four women to anchor my book Shakespeare's Sisters: Four Women Who Wrote the Renaissance, but there are many more who deserve our attention. During Mary Sidney's childhood, Isabella Whitney, a woman who worked for a while as a servant and described herself as 'whole in body and in mind, but very weak in purse', published a book of love poems and a second collection of verse and prose in 1573.

Whitney's contemporary Anne Vaughan Lock was a religious writer in the mid-sixteenth century: a passionate Protestant who fled to Geneva to escape from the Catholic Mary I.

Mary I (1516–1558) (Mary Tudor)

Antonis Mor (1512–1516–c.1576) (after)

Lock translated Calvin's sermons into English and wrote a paraphrase of Psalm 51 in the form of 21 sonnets, both published anonymously in 1560. Four hundred years later, she was identified as the author.

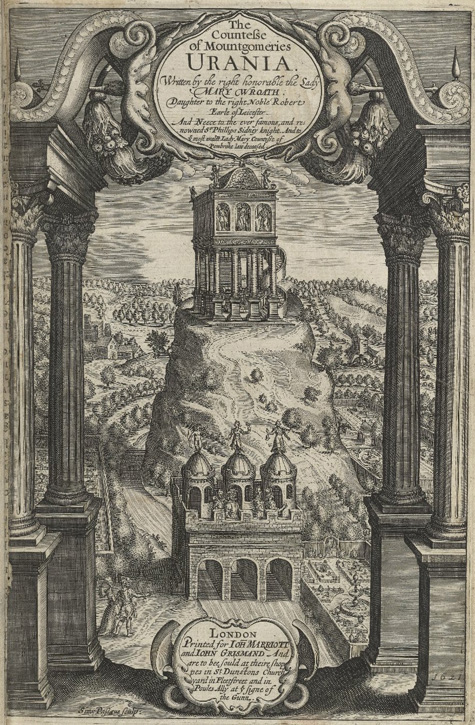

In the generation of Elizabeth Cary and Anne Clifford came Mary Sidney's niece Lady Mary Wroth, who followed in her aunt's path. Wroth's Countess of Montgomery's Urania, published in 1621, was the first prose romance published by an Englishwoman. This complex tale involved characters who were only loosely disguised from Wroth's contemporaries, creating a court scandal which led Wroth to claim she never intended for the book to be published. Appended to the Urania was Wroth's collection of 103 sonnets and songs, Pamphilia to Amphilanthus. For the first time in English literary history, a woman took on the celebrated form of the sonnet – but reversed the gender roles so that now a female poet was describing her unrequited love for her male beloved, not vice versa.

The title page of Lady Mary Wroth's 'The Countess of Montgomery's Urania'

1621, illustration by Simon van de Pass (1595–1647)

If we cast our gaze a bit later, two significant women writers stand out. Margaret Lucas Cavendish, a passionate intellectual who published no fewer than 14 books between 1653 and 1668 – ranging in genres from natural philosophy and satire to poetry, plays and romance – became famous for her work of science fiction, The Blazing World. The story focuses on the intergalactic adventures of a shipwrecked woman who becomes the empress of her new land.

A decade or so after Cavendish's works appeared in print, the first truly professional woman writer came onto the scene. Born around 1640 to a wet nurse and a barber, Aphra Behn lived for a while in the Dutch colony of Surinam before becoming a spy for Charles II in Antwerp. Due to her inadequate pay – she may even have served time in a debtor's prison – Behn took up her pen to earn her living through writing.

Starting in 1670 she wrote no fewer than 19 plays which were performed on the London stage. Behn's best-known work was her novel, Oroonoko, which tells the story of an African prince who was abducted and sold into slavery. Drawing upon Behn's own experiences in the colony, the novel took what was considered a radical abolitionist stance.

Frances d'Arblay ('Fanny Burney')

c.1784–1785

Edward Francis Burney (1760–1848)

It's tempting to imagine what it would have been like if Behn or any of the other extraordinary women who followed in her wake – Fanny Burney, Mary Wortley Montagu, Mary Wollstonecraft, to name a few – had had easy access to the works of their Renaissance sisters. Generations of women writers who came after them couldn't access their work; they were forced instead to turn inward for inspiration without models to emulate and surpass. But we can access them. We can hear their words and learn their lessons, and the more of these voices we can uncover, the richer our own history becomes.

The future of the past is full of women.

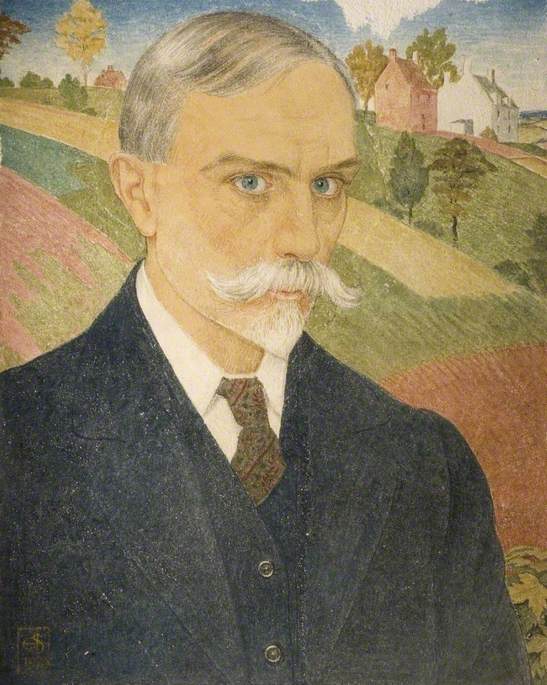

Ramie Targoff, author

Ramie's book Shakespeare's Sisters: Four Women Who Wrote the Renaissance is published by riverrun