This year Dulwich Picture Gallery is running a series on great works in their permanent collection of Old Master Paintings. Lettie Mckie spoke to Assistant Curator Helen Hillyard on the unveiling of the most recent display 'Dou in Harmony'.

Housed in England’s first purpose-built art gallery designed by Sir John Soane in 1811, Dulwich Picture Gallery’s collection of European paintings from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries includes works by Rembrandt, Watteau, Canaletto, Rubens and Gainsborough among many others. It is one of the world’s finest collections of Old Masters originally put together for the last King of Poland Stanislaus Augustus by founders Francis Bourgeois (1756–1811) and Noel Desenfans (1745–1807).

The pair dedicated five years to the task of building a Polish Royal collection from scratch, however in 1795 Stanislaus was forced to abdicate. Initially they attempted to resolve this situation by finding another monarch to take the paintings. They approached the Tsar of Russia and the British government but eventually realised they would not be able to sell the collection as a whole. Upon Desenfan’s death in 1807 Bourgeois decided to bequeath the collection to Dulwich College and expressively stated in his will that the paintings should be made accessible for ‘the inspection of the public’.

The collection celebrates the centenary of its 1817 opening next year, and is characterised by artists who made a name for themselves through daring experimentation and individuality. Spanning 1600 to 1750 it is displayed geographically with Italian, Spanish and French paintings at the north end of Soane’s enfilade followed by Flemish, Dutch and British at the south end. The works are hung against a deep ‘Soane’ red backdrop, a colour mixed by Farrow & Ball to match an original paint sample from the walls. Rarely has a collection worked so well as whole to reflect the astonishing breadth of style and technical brilliance of master works from across Europe.

In recent years the curators have made several significant discoveries about paintings in the permanent collection. In 2009 the Gallery’s prized fragment of Veronese’s Petrobelli Altarpiece (c.1563) was briefly re-united with the other surviving parts including the previously lost Head of Saint John the Baptist, which was found by chance in the Blanton Museum of Art in Texas by the then chief Curator Xavier Salomon. More recently in 2012 a previously demoted Venus and Adonis (1553–1556) was reattributed to Titian’s workshop and beautifully restored.

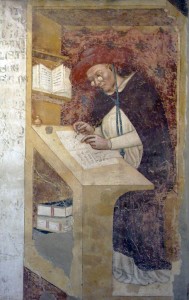

The Venus and Adonis was hung at the end of the enfilade, which made it the focal point for the entire gallery and the current display continues in this vein. 'Making Discoveries: Dutch and Flemish Masterpieces' is a series of in-focus displays showcasing four major artists from the Gallery’s collection: Van Dyck, Dou, Rubens and Rembrandt. Assistant curator Helen Hillyard said ‘The "Making Discoveries" series as a whole is born out of the research for our Dutch and Flemish Paintings Catalogue (available later this year). This has been a huge project, which has taken many years to come fruition’.

Each display draws connections with guest works from other institutions and private collections. The series celebrates each artist’s creative process with x-ray and technical analysis revealing intriguing compositional change alongside fresh research into the development of the artists’ careers.

The year started with 'I am Van Dyck' and included the National Portrait Gallery’s major recent acquisition of his last self portrait of c.1640. The portrait was displayed alongside contemporary artist Mark Wallinger’s works Self Portrait (Times New Roman) (2012) and I Am Innocent (2010) to explore different notions of self portraiture. The display also revealed new information around some of the Gallery’s best-known works by Van Dyck, including Samson and Delilah (c.1618–1620). A recent x-ray showed how Van Dyck re-interpreted Rubens’ version of the scene and intensified the drama with changes he made to the figures. X-rays and drawings illustrated how Van Dyck developed and altered his compositions over time.

In April the 'Rubens’ Ghost' display offered a unique insight into the ideas and working methods of the Flemish baroque painter, Peter Paul Rubens, focusing predominantly on the changes the artist made to the gallery’s Venus, Mars and Cupid (c.1635). A life size x-ray revealed the alterations Rubens made to the position of Cupid’s and Venus’s legs, and to Venus’s drapery. Hillyard commented ‘the full-size x-ray we had on display for "Rubens’ Ghost" made it much easier to see the changes between the x-ray and the finished version. Now, when I look at the painting, I feel I have a much better understanding of what’s happening beneath the surface.’ Speaking before the unveiling of this display Chief Curator Xavier Bray explained; ‘Now the public will be better able to appreciate the challenges Rubens was confronted with when devising his composition. The position of Cupid, for example, clambering onto Venus’s leg as he holds onto her drapery and opens his mouth to receive a jet of milk from her breast, posed a particular compositional problem for Rubens. Not being satisfied with one position, he changed it as he was working, a detail not appreciated until an x-ray was taken.’

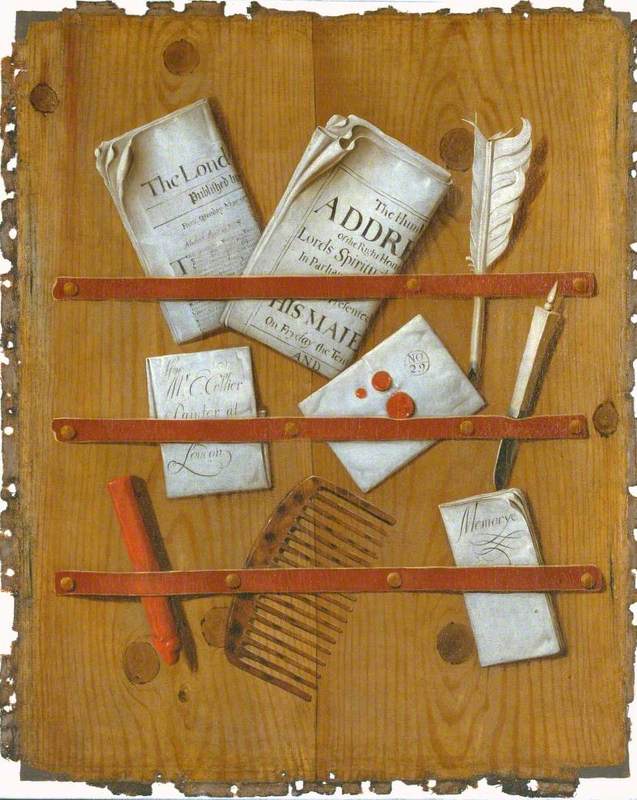

In the current display 'Dou in Harmony' two of Gerrit Dou’s finest musical-themed paintings are hung together; the Gallery’s own Woman Playing a Clavichord (c.1665) and A Young Lady Playing a Virginal (c.1665), which recently sold at Christie’s and is now in a private collection.

Hillyard said of this pairing ‘For me, it was very exciting as these are Dou’s only paintings on this theme and it will be the first time they have been exhibited together since 1665, where they were displayed in an exhibition organised by Dou’s patron Johan de Bye. To see these paintings next to each other, after close to 350 years apart, is incredibly moving’.

Bringing the two paintings together highlights Dou’s different approaches to the same subject and the means by which he invites the viewer to play an active part in the paintings’ story and meaning. Through his meticulous style and construction of architectural space, Dou draws the viewer’s eye into the picture. Displayed together the intimacy and private exchange between viewer and sitter is revealed.

The juxtaposition of these two exquisite examples of seventeenth-century Dutch realism is a sumptuous visual treat. Woman Playing a Clavichord is a much loved highlight of the Gallery’s collection but it is rarely seen on such prominent display. Placed together the paintings are a striking example of how barely noticeable changes in composition, pose and facial expression can entirely alter the meaning of a painting, revealing the artists ability to denote nuances of human emotion and behaviour. The intimacy of the Clavichord scene where a woman sits alone next to a half empty wine glass and abandoned instrument speaks of an absent lover and presents a subtle contrast to Young Lady Playing a Virginal. At first glance the paintings seem almost identical but on closer inspection the woman’s gaze in the Virginal scene is much more direct. The scene includes a group of figures in the background and a more convivial atmosphere than the privacy of Clavichord, the implication being that this young lady is a courtesan.

Evoking the mood of Dou’s seventeenth-century works, the display is complemented by a contemporary sound installation in the Gallery’s Mausoleum, composed and played on the viola da gamba by Liam Byrne (The Guildhall School, London). Taking its cue from seventeenth-century musical practice, this modern piece aims to evoke the mood of Dou’s paintings, inspiring reflection and contemplation on its themes.

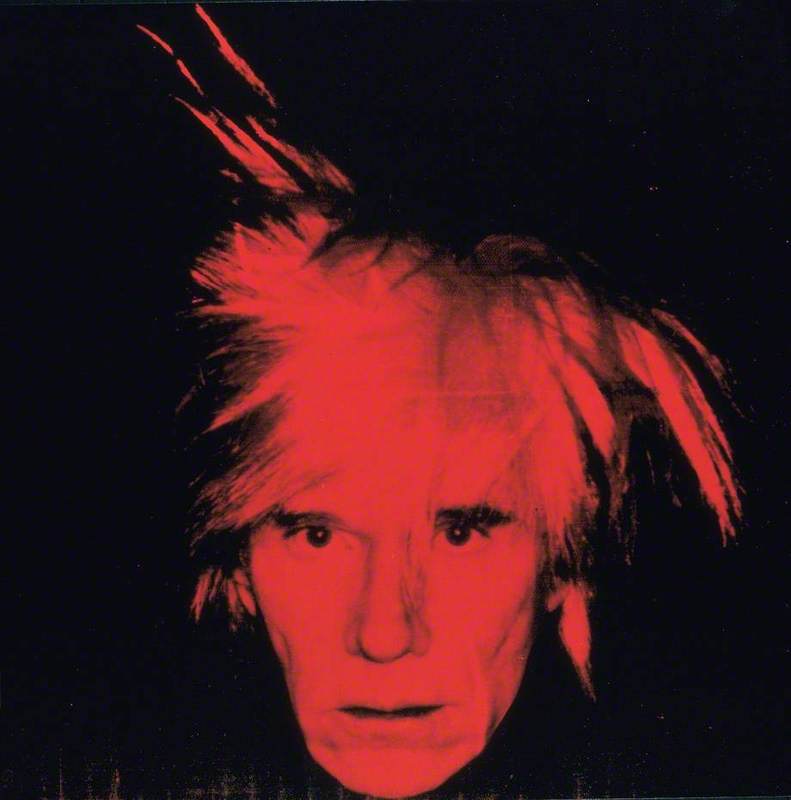

Hillyard revealed what’s coming up saying ‘Our next and final display in the series – will be "Am I Rembrandt?" Where we will be borrowing the recently re-attributed Self Portrait, Wearing a White Feathered Bonnet (c.1635) from Buckland Abbey, Devon (National Trust). This presents a fantastic opportunity to re-examine the attribution of our own Rembrandt paintings. We have certain works, such as our portrait of Jacob III de Gheyn (c.1632) whose status is unquestioned, and then we have others like A Portrait of a Young Man (c.1663), which is far more problematic. I think the display will raise a number of interesting questions, for instance, what makes a Rembrandt a Rembrandt? And, if a painting loses that attribution, does it change the way that we view it?’

She also mentioned ‘Our Dutch theme will also continue with our next temporary exhibition "Adriaen van de Velde: Master of Dutch Landscape" (12th October 2016 to 15th January 2017), which aims to reintroduce the work of this prolific albeit tragically short-lived artist; exhibiting his paintings alongside meticulously drawn preparatory studies’.

Summing up the series as a whole Hillyard said ‘"Making Discoveries: Dutch and Flemish Masterpieces" has allowed us to take a new perspective on some of our best loved paintings. For seasoned art lovers, it’s a chance to look at familiar works in a completely new light. For those new to Dulwich Picture Gallery, it’s the perfect introduction to how and why artworks are made’.

Lettie Mckie, freelance writer

'Dou in Harmony' runs until 6th November 2016.

The last display in the 'Making Discoveries: Dutch and Flemish Masterpieces' series' 'Am I Rembrandt?', runs from 8th November 2016 to 5th March 2017.

Dulwich Picture Gallery’s Assistant Curator Helen Hillyard has written a series of essays with Smarthistory to accompany the series.

.jpg)