In September 2019, the first of Donna Tartt's three novels made its transition to the big screen. Teased for years with promises of film adaptations, her fans are at last able to see her words come to cinematic life.

The Goldfinch is a novel that begins with an explosion, the shattered pieces of which its hero, Theo, struggles to put back together until its very end. From the rubble at the epicentre of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Theo pulls Fabritius' The Goldfinch, a painting that is woven in and out of the narrative of the text, haunting Theo's life and serving as a reminder of the tragedy of losing his mother in the blast. He is chained to it, just as the eponymous goldfinch is chained to its perch, a glowing bird constrained by the narrow parameters of the canvas.

The Goldfinch

1654, oil on panel by Carel Fabritius (1622–1654)

The real painting is not in The Met in New York, but in fact on display in the Mauritshuis in the Netherlands.

The painting of The Goldfinch is a potent emblem of destruction in itself. Fabritius worked in the brief period between 1641 and 1654 until he was killed in a massive explosion, the brevity of his career granting him paradoxically longer life, as it so often does for musicians who die young and at the height of their powers.

Fabritius was born in Middenbeemster, a village outside Amsterdam in 1622, the son of a father who was a part-time painter, in between working as a teacher and sexton. Fabritius' early education must have come from his father, who similarly fostered the artistic talents of Carel's two brothers, Johannes and Barent. In 1641 he married Aeltge Velthuys, his next-door neighbour.

A Young Man in a Fur Cap and a Cuirass (probably a Self Portrait)

1654

Carel Fabritius (1622–1654)

In the same year, we think, he made the short journey into Amsterdam to study alongside his brother Barent, under the master of shadow, light, and intense portraiture, Rembrandt van Rijn.

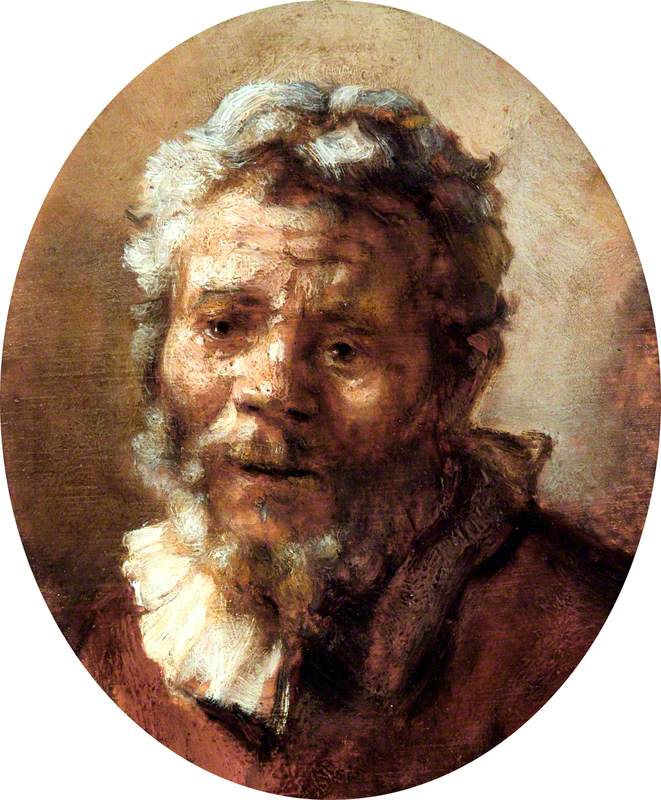

You can see echoes of Rembrandt's style in Fabritius' use of shade in his Portrait of a Bearded Man, as well as a similar fascination with the decrepitude of old age.

Facts about Fabritius' life are slightly uncertain, but it appears that he worked in Rembrandt's workshop until about 1643, when Aeltge died in childbirth, a tragic resonance, maybe, with the loss of Theo's mother in Tartt's book. It is perhaps this short apprenticeship under Rembrandt that accounts for the fact that Fabritius was the only one of Rembrandt's pupils to develop his own distinct style. In contrast to the master, Fabritius preferred light, warm backdrops instead of deep blacks. Fabritius also did away with the heavy iconography of Renaissance painting and moved towards a more technical approach to painting. Areas of impasto are balanced in his work with the delicacy of thin glazes, allowing him to play with heaviness and lightness. The simplicity of his works belies their complexity, capturing everyday scenes with perfection.

After Aeltge's death, Fabritius returned to live with his parents, producing in that year his earliest dated painting that still exists (except a work that is estimated to have been produced in 1640, and now hangs in the Rijksmuseum). This painting and subsequent compositions focus on biblical, classical, or more quotidian subjects, very typical for the period.

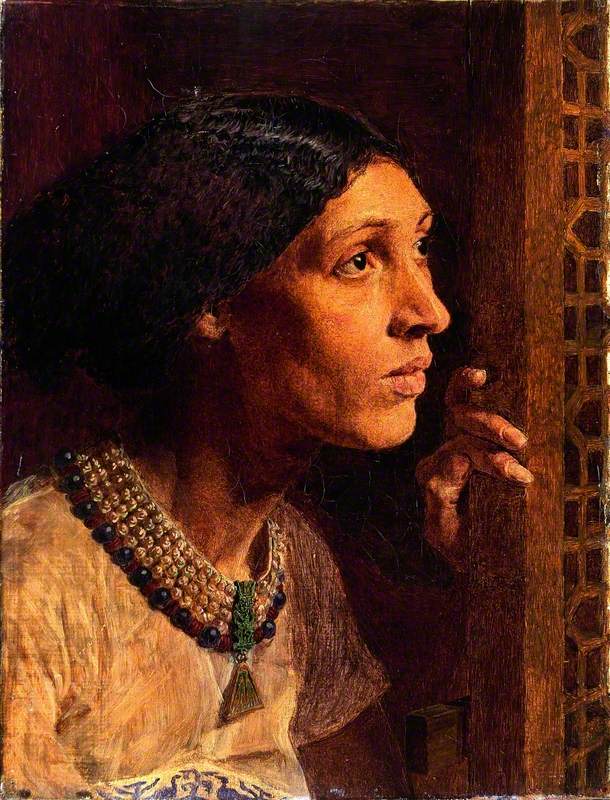

In 1650, Fabritius moved to Delft, and in the same year married Agatha von Pruyssen. Delft was home to several other renowned artists of the time – among them were Johannes Vermeer, Nicolaes Maes, and Pieter de Hooch. Together they formed the Delft School and became known for their views of their city and its daily life, as well as quieter and more considered interior scenes. Fabritius' A View of Delft, with a Musical Instrument Seller's Stall is a panoramic reflection of the School's subjects. The still life in one half of the painting is offset by the depiction of the Nieuwe Kerk, facing the Town Hall of Delft.

A View of Delft, with a Musical Instrument Seller's Stall

1652

Carel Fabritius (1622–1654)

Fabritius joined Delft's Guild of Saint Luke in 1652, at a time when the art market was in crisis, perhaps due to the frequent state breakdowns in this period. However, Fabritius was producing important work – many of the pieces that we have now are from this point in his life. He had also taken on a pupil and was referred to by his widow as 'painter to his Highness, the Prince of Orange' (an unsubstantiated claim).

Then, tragedy. As the explosion of Tartt's The Goldfinch rips through her book and through the lives of her characters, so too did an explosion destroy Fabritius and a large part of his work. On 12th October 1654, a magazine storing about 30 tonnes of gunpowder detonated, wounding thousands, and killing about a hundred, among them Fabritius. He was killed in his workshop by the explosion, known as the Delft Thunderclap, which destroyed the large majority of his works. His early promise was unrealised, the evidence largely obliterated.

However, The Goldfinch survived, one of only three from the year that Fabritius died. The fragility of its subject adds poignancy to the painting, as well as the reminder that canaries, a similar flash of light, were later used to detect explosive gases in mines. As Theo describes it in the wreckage of The Met: 'Tiny yellow bird, faint beneath a veil of white dust.'

Theo, still reeling from his explosion, finds some sense from what he pieces together from the fragments of its aftermath. At the heart of it is Fabritius' Goldfinch: 'the painting has also taught me that we can speak to each other across time'. From it, and from his own life he learns:

'That life – whatever else it is – is short. That fate is cruel but maybe not random... And in the midst of our dying, as we rise from the organic and sink back ignominiously into the organic, it is a glory and a privilege to love what Death doesn't touch. For if disaster and oblivion have followed this painting down through time – so too has love. Insofar as it is immortal (and it is) I have a small, bright, immutable part in that immortality.'

India Lewis, writer and co-founder of @radicalwomenshistory