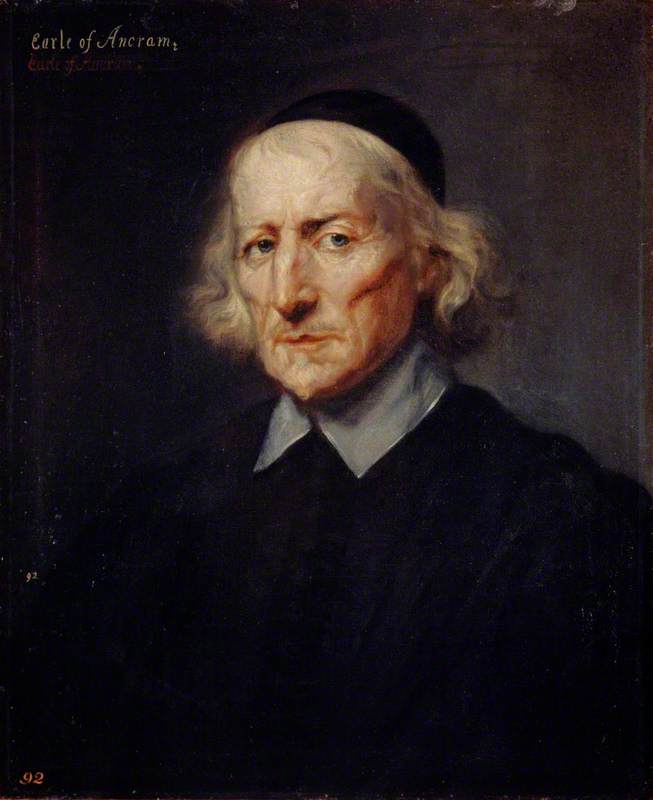

The Walker Art Gallery's Rembrandt self-portrait is the first portrait of the Dutch artist to have entered Britain.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

c.1630, oil on panel by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

It is also one of the best documented of the 80 or so self-portraits that Rembrandt produced in painted and print form. The portrait was already in the royal collection of Charles I at Whitehall Palace by 1639, when it was described very precisely in the meticulous inventory written by the Surveyor of the King's collection, Abraham van der Doort, who was himself a Dutchman. He wrote:

'above my Lo: Ankrom's doore the picture done by Rembrandt being his owne picture done by himself in a black capp and furred habbit with a little goulden chaine uppon both his shouldrs In an oval and square black frame. Given to the Kinge by my Lo: Ankrom.'

The 'Lord Ankrom' in question was Sir Robert Kerr, made 1st Earl of Ancram in 1633, who presented the Rembrandt self-portrait as a gift to Charles I sometime before June 1633, along with another Rembrandt, An Old Woman, called 'The Artist's Mother', which is still in the present-day Royal Collection.

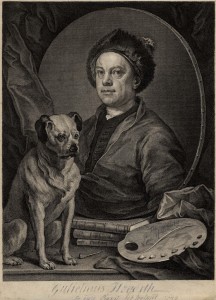

Robert Kerr (1578–1654), 1st Earl of Ancram, Royalist

1654

Jan Lievens (1607–1674)

As one of Charles I's most loyal Scots courtiers, he was keen to curry favour with the King. Kerr had probably acquired the painting during or after 1629, when he made a lengthy visit of at least nine months to the Dutch court of Prince Frederik Henrik at The Hague, to attend the funeral of Charles I's nephew, and see his own son, who was serving in the Prince's army.

Kerr's close friend at the Hague court was the Prince's Secretary, Constantijn Huygens, one of whose tasks was to scout out artists for the court of his employer.

Portrait of Constantijn Huygens and his (?) Clerk

1627

Thomas de Keyser (1596/1597–1667)

By 1629 Huygens had already talent-spotted the young Rembrandt, when the artist was still working in his native Leiden.

The Prince was also keen to retain the favour of Charles I for diplomatic and military reasons, as part of an Anglo-Dutch alliance against the Spanish Habsburg monarchy, for whom the Flemish Catholic painter Peter Paul Rubens was acting as an artist-diplomat. A gift to an art-loving monarch such as Charles I of a self-portrait by a rising star of the Protestant Dutch art world would have been very appropriate.

Rembrandt may also have been aware that his self-portrait would end up in the prestigious collection of Charles I, as he has painted himself not in his humble work clothes, but wearing a fur-trimmed cloak over which is prominently draped a gold chain – the traditional symbol of a court artist since the sixteenth century.

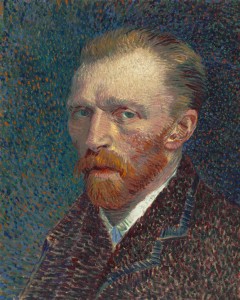

Perhaps he was hoping to attract British royal attention in the same way that his older contemporary Peter Paul Rubens had already done with his A Self-Portrait – Rembrandt owned a 1630 engraving of this work. By making an impression Rembrandt might have hoped to be invited to Charles I's court just as his friend and Leiden rival Jan Lievens was in 1632. Instead, in 1631, Rembrandt moved to Amsterdam where he became renowned for his portraits and narrative scenes of religious and classical legend.

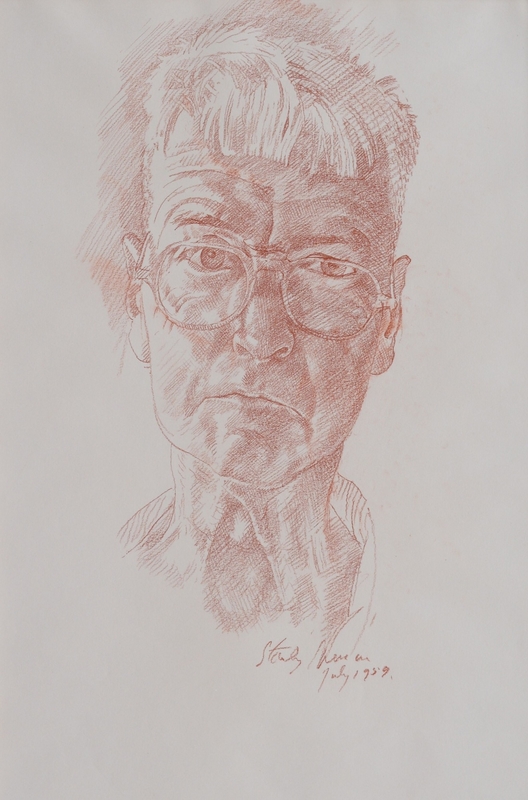

Self-portrait open-mouthed, as if shouting

1630, etching by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

Compared to Rembrandt's earliest painted and etched self-portraits, with their wild abandoned hair, exaggerated expressions, and faces cast in deep shadow, the Walker's is more formal and larger, but it retains their evocative handling of light and shade.

Self Portrait at the Age of 22

c.1623–c.1629

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) (studio of)

The golden halo of light, against which Rembrandt silhouettes his head, focuses our attention on his face. His concentrated gaze gives an impression of the intense scrutiny Rembrandt gave himself in the mirror. More practically it allowed the young artist to avoid painting that difficult piece of anatomy, particularly in a self-portrait, the hands.

Rembrandt's signature on the self-portrait

The signature Rembrant [sic], painted in red in the upper-left corner, appears to be original. Its format, without any mention of Leiden and without the letter 'd' (before the 't'), was used by Rembrandt very briefly in about 1631–1632, after he had moved to Amsterdam.

Rembrandt chose not to use a new, and therefore costly, wood panel as his support, but instead reused an oak panel and painted over a small standing figure of a man wearing a hat or helmet.

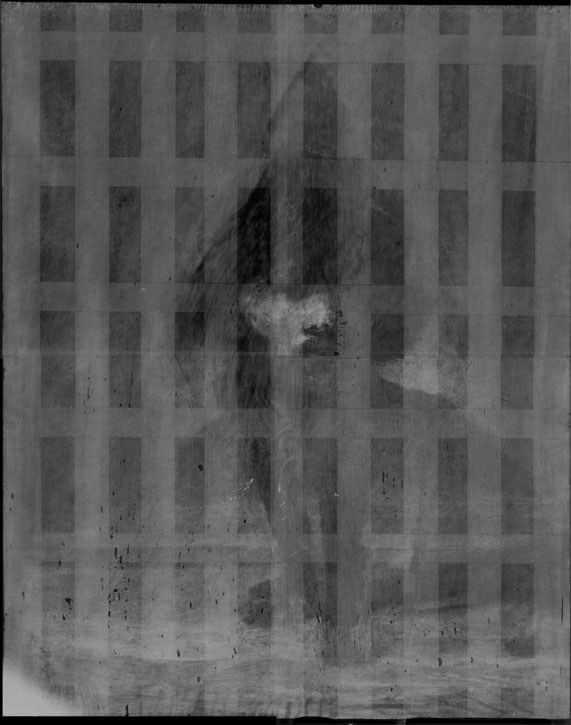

An x-ray of the Rembrandt self-portrait

The grid-like 'cradling' (visible under x-ray) was added centuries later to control the warping of the wood. By then the panel had already been thinned, so removing from the back the tell-tale Latin monogram CR (Carolus Rex) that would have revealed it as having belonged to Charles I.

Like all of Charles I's collection, the self-portrait was auctioned off at the huge sale held between 1649 and 1651 after the king's execution. One person who bought about 120 items from the sale was Philip Lord Lisle, 3rd Earl of Leicester, a member of Oliver Cromwell's government. He may possibly have acquired the self-portrait, as one of his properties was Penshurst Place in Kent, from where in 1948 the self-portrait was sold. In 1953 it was bought by a Liverpool firm – the Ocean Steam Ship Company – on behalf of the Walker Art Gallery, in time to celebrate the young Elizabeth II's coronation.

Rembrandt used his early self-portraits to explore the effect on the overall mood of an image of the fall of light and shade over and around the face, before embarking on portraits commissioned by the merchants of Amsterdam. He built his reputation not just on a masterly ability to capture the texture of clothing, hair and skin, as he does here, but also as one of the most psychologically acute portraitists – a reputation that he still has today.

In Amsterdam, Rembrandt made his name as a pictorial storyteller, and for his innovative technique, both as painter and printmaker. His mastery of printmaking is explored further in a touring exhibition from the Ashmolean, 'Rembrandt in Print', on display at the Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight, until 15th September 2019, and then at Holburne Museum, Bath.

Xanthe Brooke, Curator Fine Art (European) at Walker Art Gallery, National Museums Liverpool