The German writers Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Johann Peter Eckermann were not big on glasses. The former thought 'they destroy all fair equality between us... for what do I gain from a man into whose eyes I cannot look when he is speaking?'

Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

c.1800–1820

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) (follower of)

For Eckermann, glasses wearers were 'conceited' because their spectacles 'raise them to a degree of sensual perfection which is far above the power of their own nature.' But in their griping, I see sensitivities which could be summed up by what Neil Handley, curator of the British Optical Association Museum has called 'the psychology of wearing spectacles'. We most often encounter the symbolic power of spectacles in literature – Piggy's glasses in Lord of the Flies spring to mind – but for centuries art has reflected the meanings glasses have held for us since their invention.

A Venetian Procurator

c.1620–1629

Jacopo Palma il giovane (1544/1548–1628) (style of)

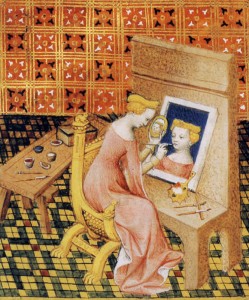

The use of a glass lens as a visual aid has roots in antiquity, but the development of what more closely resembles what we call glasses, i.e. two circular lenses held together by a frame, began in Italy in the late thirteenth century. Religious scholars were among the first to develop a significant symbolic relationship with glasses. In fact, the first depiction of glasses in European art is in a series of frescoes in the church of St Nicholas, Treviso, which were completed by Tommaso da Modena in 1352. One panel depicts Cardinal Hugh of Saint-Cher (c.1200–1263) in deep concentration, pen in hand and spectacles sitting high on the bridge of his nose.

Hugues de Saint-Cher

1352, fresco by Tommaso da Modena (1326–1379), in the chapter house of the church of San Nicolò, Treviso, Italy

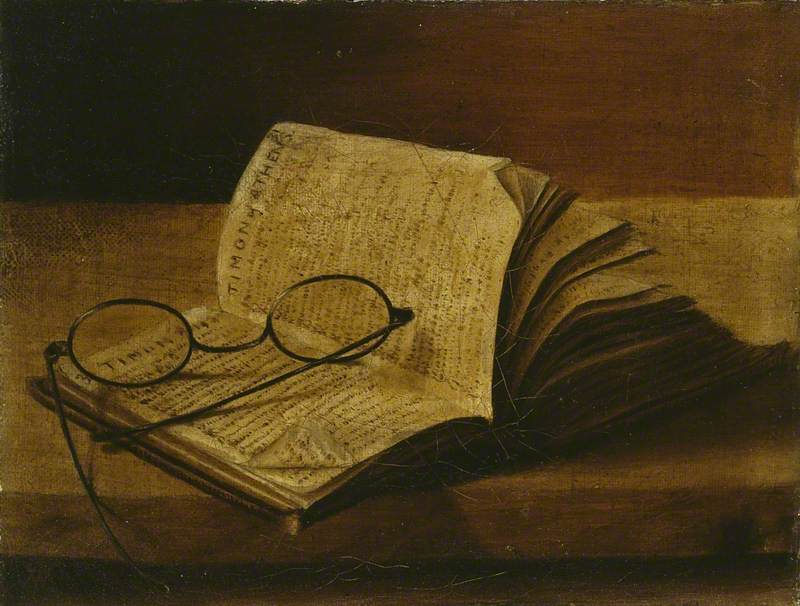

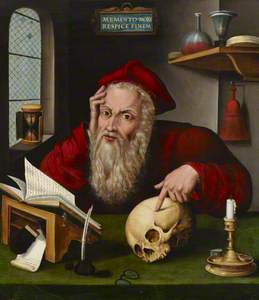

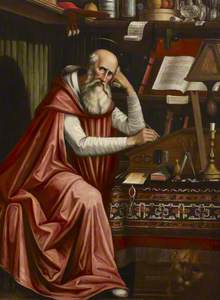

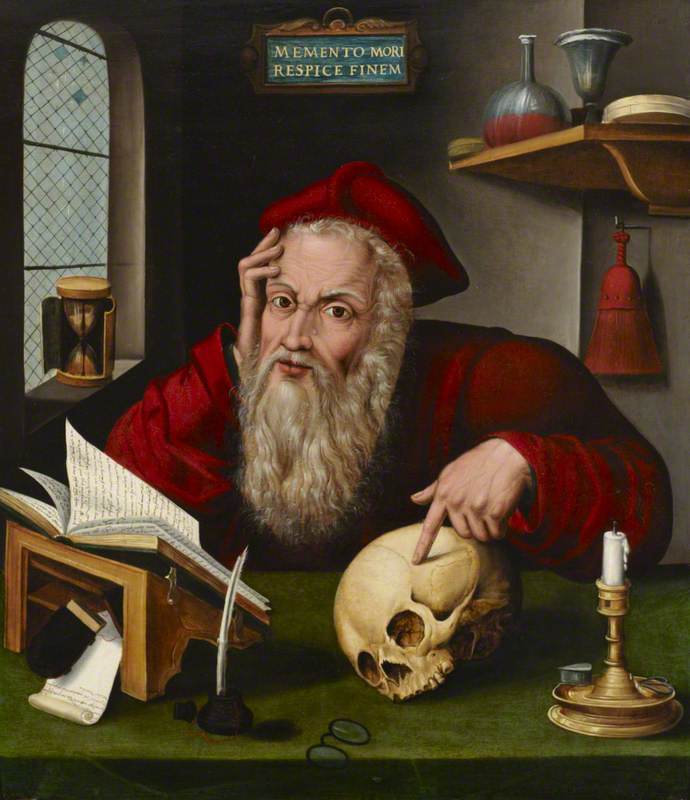

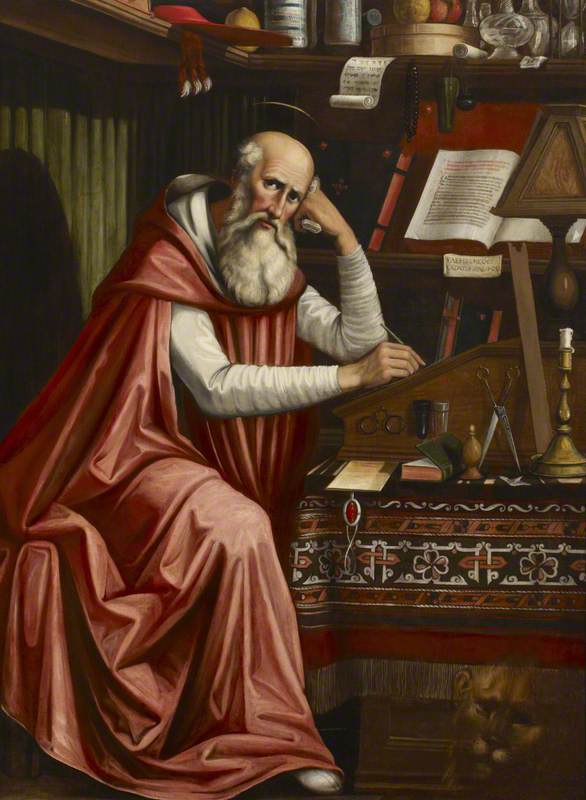

In many depictions of Saint Jerome, who is known for translating the Bible into Latin, his glasses sit on or near his writing desk, presented to the viewer as the instrument of the scholar much in the way a stethoscope is irrevocably linked nowadays to doctors.

Saint Jerome in His Study

possibly 16th C

Joos van Cleve (c.1485–1540 or 1541) (copy after) and Marinus van Reymerswaele (c.1490–c.1567) (copy after)

However, the appearance of glasses in the images of Cardinal Hugh and Saint Jerome are anachronistic: both figures lived and died well before their invention. But they show how early an association between wisdom and spectacles developed so that their appearance became a useful shorthand. In Saint Jerome's case, the anachronism was so persistent that he became the patron saint of spectacle makers.

Saint Jerome in His Study

(copy after Domenico Ghirlandaio) 17th C/18thC

Italian School

By the fifteenth century, Florence was the centre of a thriving and innovative spectacle industry. By the sixteenth century, one could see spectacle pedlars on the streets of western Europe as the trade expanded to cities like Nuremberg, Germany where, in 1535, the establishment of regulations for the Spectacle Makers Guild sparked an industry with a reputation to rival the Italians.

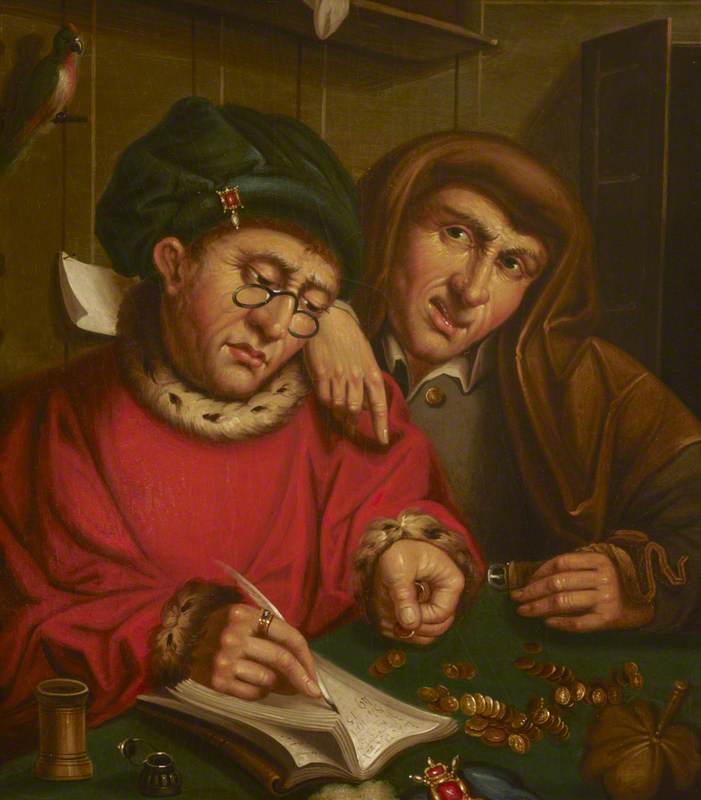

The Misers, a seventeenth-century genre painting in the style of David Ryckaert III (1612–1661), depicts an elderly woman wearing Nuremberg-style nose spectacles as she and an elderly man weigh coins. The image conveys how, by this time, glasses had picked up negative connotations, and were often used to convey stinginess and culturally-disdained professions such as tax collecting.

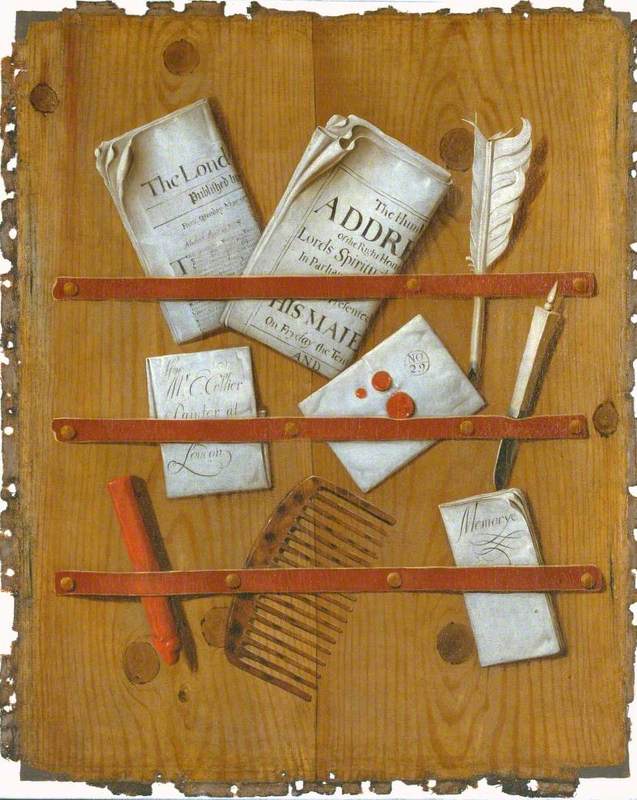

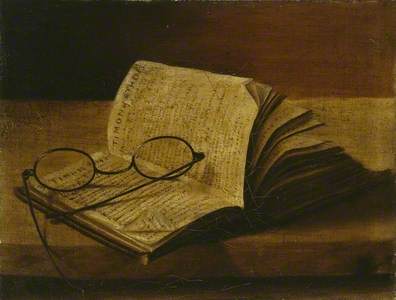

Jan Davidsz. de Heem's (1606–1683/1684) Memento Mori depicts a pair of nose glasses between cut flowers in their last gasp of vitality and an overturned skull. While its title refers to the older tradition of the memento mori, this painting is also reminiscent of the vanitas, popular with Dutch painters like de Heem in the seventeenth century.

Here the glasses could signify intellectual pursuits with the painting overall suggesting the folly of the search for knowledge in the face of inevitable and unpredictable death. But the skull is knocked over and the glasses are at the forefront of the image. Another reading is that it could be a subversion of this artistic tradition, suggesting instead that the legacy of great intellectual achievement is a way of cheating death.

Spectacles remained largely unchanged for almost 400 years until the 1700s, when a significant innovation came about (this shift was most likely thanks to the invention of newspapers). The arms or 'sides' were developed and the C-shape bridge became popular. By the nineteenth century, nose spectacles seemed a little outdated. It's not really any surprise that the age which saw the peak of dandyism also gave us some of the most elaborately designed glasses.

José Buzo Cáceres' Portrait of a Gentleman depicts a man wearing glasses with tinted side visors which were popular during the 1830s.

Neil Handley comments on the obscuration of the gentleman's eyes, suggesting the prominence of the glasses could be to conceal something that might offend a viewer, such as the hallmarks of a disease or blindness.

As he says: 'Throughout history the sightless eye has often been covered by a patch or an occluded lens, to guard against our sensitivities and deflect prejudice, revulsion and social rejection.' But the unique style of these specs also suggests something of a fashion and status symbol.

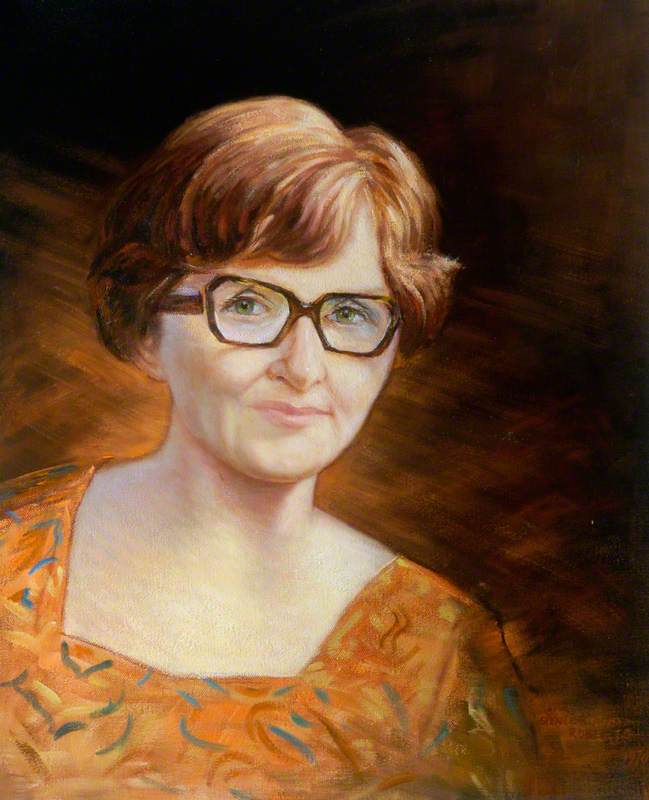

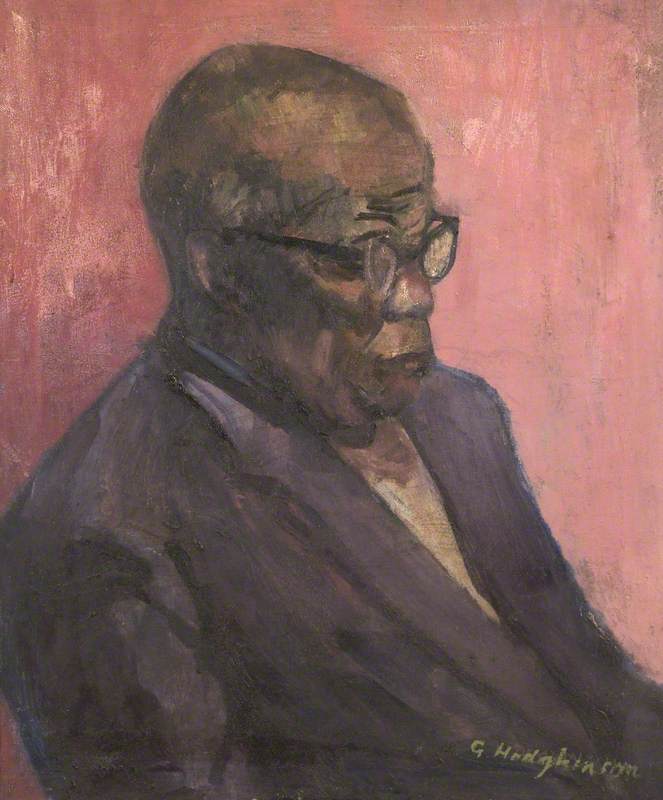

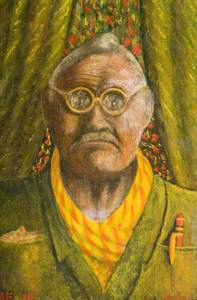

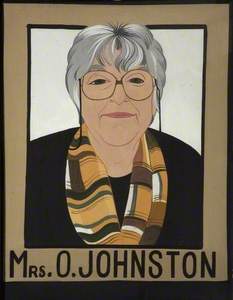

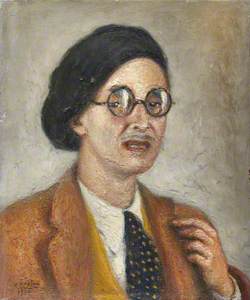

Many of the connotations, both negative and positive, that glasses have acquired in their 700-year history persist today. Portrait of an Intellectual by John Howard Jephcott (1910–1984) presents a take on the enduring association of spectacles and intellect that seems to hark back to the idea Eckermann related to Goethe: the delusion that the 'artificial eminence' which glasses afforded their wearers was authentic.

As in the Cáceres portrait, the figure's eyes are barely visible and even appear to be closed. The glasses seem to fade into the face as if part of his very skin – not a tool or accessory but part of his identity as a so-called intellectual.

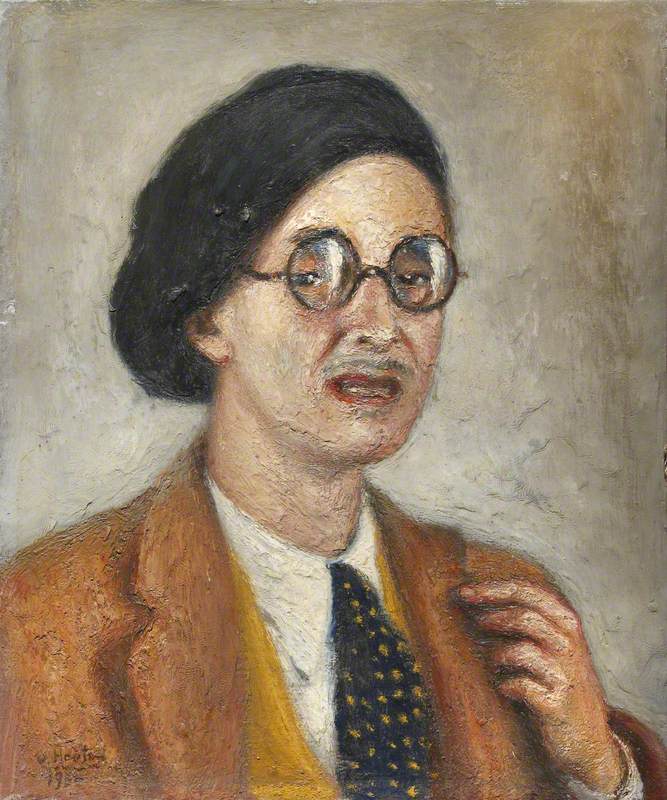

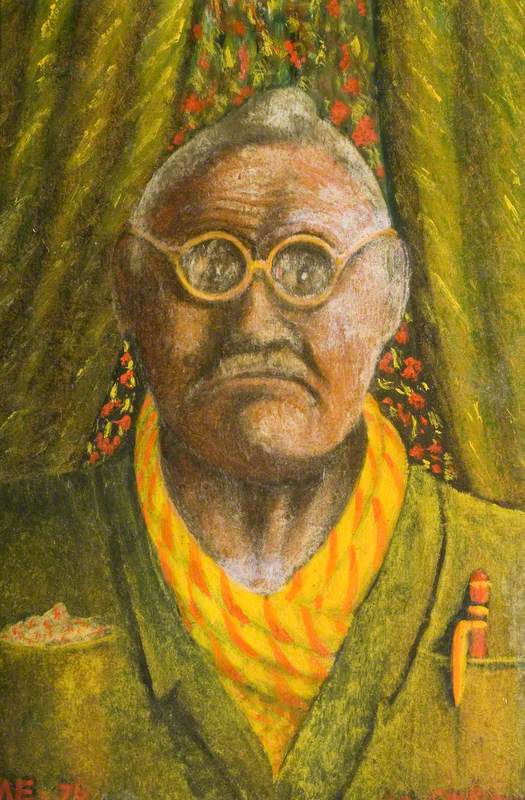

The eyes are also barely visible in amateur artist and former miner Charles William Brown's 1958 self-portrait Me, 76. The glasses appear smeared and scratched, affected by the passage of time like the portrait's subject, and looking as though they would, in defiance of their purpose, obscure his vision rather than aid it.

In Dragon and Figure, by an unknown artist, the crude lines that make up the spectacles are what help distinguish the figure in the centre of the work as specifically human. Here, the glasses are not an indicator of class, age, or profession, but personhood and the ingenuity of an invention that embodies dissatisfaction (or conceitedness if you're Eckermann) with the limits of our bodies.

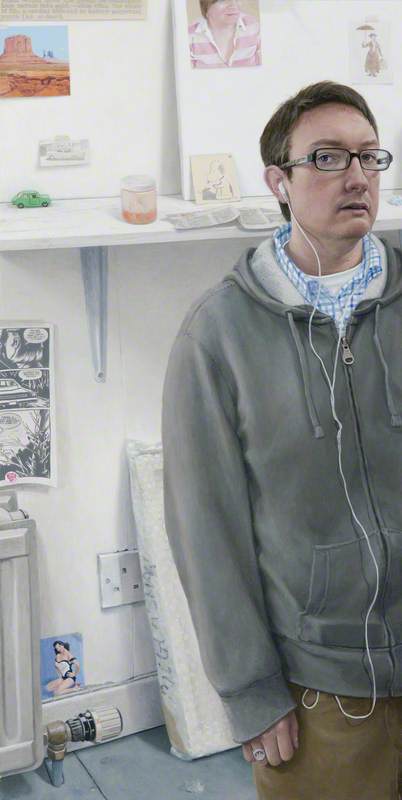

Due to twenty-first-century technological advancements, such as laser eye surgery, for many people, glasses are viewed as fashion accessories as much as they are medical aids. From a contemporary perspective, representations of glasses in fine art remind us of their perceived prestige in history, as well as our culture's ongoing spectacle stigma.

Aida Amoako, freelance writer